In ancient Rome times, the production of wine was considered an interesting business. Cato puts viticulture in first place in agriculture, as the most profitable activity and so it will be for centuries. However, it wasn’t just an economic question.

The agriculture, especially viticulture, was considered the closest activity to the founding values of the fathers, to the saving bond with the land and nature, the ideal lifestyle, an occupation capable of elevating man morally to contrary to the vice and corruption of the city life, … This “nobility” was also a matter of class. In fact, the patricians were the landowners par excellence, so they willingly praised and exalted their peculiar activity, while it was a goal of social affirmation for others. According to Cicero (De Officiis), “among the occupations in which the profit is assured, none is better than agriculture, neither more profitable, nor more pleasant, nor more suited to the free man“. Yet, his job was another. The viticulture for him was the ideal activity for the old age.

There was a good dose of idealization of agricultural life in all these definitions, especially by those who (poets, writers or wealthy owners) had never really dealt with the hard life of the fields, dominated by the uncertainty of the year. Precisely in this period the agricultural world entered Arcadia thanks to Virgil, who first thus defined a literary topic of great success in the centuries to come. The Arcadia of Virgilio is no longer just the natural landscape but also the agricultural one, where benign Nature abundantly gives its fruits to the man skilled in his work.

We, however, are not literatus but vintners. Who works the land can love it without myths or bucolic visions, well knowing even the most difficult aspects. Certainly, the Roman farmers did not ignore them, as Cicero on the other hand, who clearly describes the risks and inconveniences of agricultural work in one of his famous orations (Ad Verrem).

Let’s now understand the real life of the winegrower of the time, of which I will tell in this and other posts to follow. I begin by remembering a little Roman agricultural history, then going to see who our colleagues of the time were and then how they worked. Much has changed since then, yet something is similar to our present.

[one_second][info_box title=”The wonderful Palaemon’s vineyard

” image=”” animate=””]

A vivid example of the viticulture of the time is provided by Pliny the Elder, who tells of a wonderful vineyard and brings it as an example of the great value of this activity.

It was owned by a grammarian (= high school teacher) very famous at the time, Quintus Remmius Palaemon. He was a freedman originally from Vicenza, an ex-slave who not only freed himself, but became very rich and famous. He is remembered for his contribution to the Latin language, for having introduced the study of Virgil’s works in schools, but also for his vices and arrogance.

In the period of Nero (55 or 57 AD), Palaemon purchased an uncultivated land in the Ager Nomentanus, at ten miles outside Rome, of just under 60 jugeri (about 15 hectares). The area was considered among the most renowned for wine, after the Falerno area. Pliny says that Palaemon had bought that land for little money, even if he had invested a lot for the vineyard planting, which was a very expensive operation today as at the times. In total, he had spent six hundred thousand sestertii.

He had given the contract for the works (the trenching, the plantation of the vineyard and then also its management) to his neighbor winegrower, Acilius Sthenelo, also a freedman. Pliny let us know that he was a vintner of proven ability and that it was he who had advised Palaemon on this whole affair. The contractor, then called conductor, is a farmer who, in addition to his own fields and vineyards, also works for others, thanks to his professionalism, manpower and tools.

Palaemon outsourced the bulk of the work and sold the grapes on the plant. Clearly the grammarian was an entrepreneur who wanted to make the most of his vineyard with minimal expenses. Pliny himself points out that Palaemon had not been driven by the love of viticulture in all this, but by his enormous and well-known vanity. Is Pliny pungent for class snobbery? In Rome, a slave could also ascend socially but he carried the mark of his origins all his life. However, at the times as now, it is certainly a boast to have the vineyard among the rich and powerful!

Pliny writes that, in the eighth year (the year of entry into full production for a vine trained to a tree, i.e. the ancient Roman viticulture form), the grammarian gained 400,000 sesterces from the sale of the grapes, 2/3 of the whole cost of the vineyard. According to Pliny, it is a very important profit. He compares it to the profits from the trade with the Indies.

Suetonius also tells of the wonderful vineyard (in his work De Grammaticis et rhetoribus). He claims that one of these vines can produce 360 bunches! This disproportionate number is perhaps a hyperbole to highlight the excellence of the vineyard (Suetonius was certainly not an agronomist). However, the traditional Roman vine training system, the “married vine” to a tree (arbustum) can truly give a very high production.

In any case, the vineyard had become very famous. In its tenth year, Seneca wanted to buy it at all costs, even if he had to stoop to do business with a man he despised. Pliny informs us that Seneca bought it for a price that was four times that initially paid by Palaemon, two million four hundred thousand sestertii, thus concluding his demonstration of the great economic value of viticulture.

Seneca obviously bought it only for prestige reasons, certainly not to make a profitable investment. Even today it happens that a wealthy person buys a very famous vineyard or winery at a very high price.

Seneca did not continue with the sale of the grapes, but produced the wine. Who knows if it was this activity that inspired him those paragraphs in which wine or vineyard become metaphors of human existence, such as:

“I advise you (Lucilius), however, to keep what (the time) is really yours; and you cannot begin too early. For, as our ancestors believed, it is too late to spare when you reach the dregs of the cask. Of that which remains at the bottom, the amount is slight, and the quality is vile..”[/info_box][/one_second]

A people of farmers.

Rome, like any civilization, was born on agriculture which, initially, was only subsistence. Varro says that, at the beginning, Romulus assigned each citizen a plot of arable land equal to two jugeri (roughly half a hectare), the bare minimum needed to live. According to tradition, the class of patricians descended from these first inhabitants – owners of Rome. In fact, the ideal image of the ancient Roman citizen was that of the farmer, who leaves the plow or the vineyard only to hold the sword when the country calls. Cato reminds us that, to praise a man, it was used to say that he was “a good husband and a good farmer“.

In the most ancient period, Romans tried to maintain a certain balance in landed property: it was thought that the excessive enrichment of someone would destabilize the whole of society. However, it was necessary to contain human greed and Numa Pompilius, the great legislator, instituted the Terminalia feasts, a typically ancient mixture of law and religion. He ordered the Romans to delimit their fields with stones, that were consecrated to Jupiter Terminus, protector of every right and every commitment (Juppiter Terminus later became an independent divinity, the god Terminus). The boundaries were thus made sacred and inviolable. The transgression of boundaries was considered one of the worst crimes. The transgressor was considered “sacer“, that can be translated as sacred but at the same time damned: a person who had carried out actions so terrible as to place himself outside the society, entering into an area of belonging to the gods. He wasn’t prosecuted by law, but anyone could have killed him with impunity. Numa also introduced the measurement of properties during these festivals. If they exceeded 50 jugeri (about 13 hectares), the surplus was confiscated by the state. Tullus Hostilius began to grant these requisitioned lands to the paupers.

Roman hagiographic history refers us to figures of extraordinary integrity about this Roman ideal of moderation, that is, of a life governed by temperance and sobriety. We remember for example the general Curius Dentatus who, in 285 BC, refused 50 jugeri in Magna Grecia that the Senate wanted to give him, to thank him for having defeat Pyrrhus. He said he didn’t want to set a bad example. The most famous case is that of Cincinnatus who, to respond to the call of the state, left his field of 4 jugeri on the Vatican hill and returned to work it once he finished his political office, without having enlarged it (that is, without having been enriched). I also remember that the Senate had to admit among the public expenses the payment of the work of the fields of General Marcus Atilius Regolus, who had had to extend his stay in Africa but, without his work, the family risked starving to death.

These laudable examples were only exceptions. In fact, over time, imbalances became more and more accentuated, thanks also to more and more permissive laws on property.

When Rome began its first conquests, the lands of the defeaters were confiscated and annexed to the ager publicus, the state property. A part of them were sold to free citizens. The richest ones obtained not only the largest but also the best soils. A part of the lands was however given to those who could not afford to pay but, in return, had to return a part of the harvest each year. Then, the lots were also assigned to veterans of armies.

It is not easy to understand how we went from the subsistence agriculture to the birth of farms with economic purposes (villae). The era of Cato the Censor (around the middle of the second century BC) stands as a milestone in this sense, thanks to his testimony of the ongoing transformation. The first villae (farms) were medium-small and sadly we know that their growth was been mainly linked to the slave labor, the prisoners of war.

However, a period of great prosperity began for wine and its trade, as well as for Italian agriculture in general, which would remain very flourishing until the end of the Republic and the first Empire. From then on, however, a progressive decline began, for multiple reasons. The first was the birth and expansion of the latifundium (estate), as the most ancient Romans feared, which led to the loss of specialized agriculture and dependence on the import from the provinces. How did this come about? It is not easy to make a summary but I try to give an idea of the transformation of the Roman agriculture.

The large estates predominated more and more due to the progressive disappearance of small properties. Why? Even in the most prosperous era, the small-medium farmer did not always have an easy life. Several authors testify to us how huge the costs of starting and running a farm were, especially for the vineyards, and how heavy the taxes were. If we also add the risk of bad vintages, the difficulties multiplied. The small owners were often forced into debt, with little or no protection, with often very high interests.

Gradually, the small properties decreased, due to the huge costs and the usurers’ loans, which had already been reported since the time of Cato. If farmers were unable to pay their debts monetarily, they had to go to work as servants in the fields and vineyards of their creditors, neglecting their own. This form of servitude was called nexus. Those who could not even manage this situation had to sell the property, thus contributing to the enlargement of those of the rich persons. Those who remained without land abandoned the countryside and crowded into the city, living on state charity. Those who accumulated too many debts without being able to pay were sentenced to slavery.

Thus, Varro writes: “… the pater familias (fathers) gradually entered the city walls, abandoned the sickle and the plow, and prefer to use their hands to applaud in the theater and circus rather than in the cultivation of the fields and of the vineyards. So, we pay those who bring us wheat from Africa and Sardinia and make the grape harvest on the islands of Kos and Chios “.

From the late Republic onwards, the political and social unease about the progressive disappearance of small and medium-sized properties is witnessed by numerous authors of the time, with complaints of the situation or the moral incitement to return to agriculture. There are those who compose poetic praises about agricultural life, those who exalt its economic value (especially of viticulture, such as Pliny with the story of Palaemon’s vineyard). The intent is to push the Romans to return to dealing with agriculture, which is increasingly in dangerous decline.

In late republican and early imperial age, larger and larger estates arose. Cicero already denounced that, at his time, most of the agricultural lands were owned by only 2,000 families. Some politicians tried, weakly, to stem these phenomena. The emperor Nero did it brutally: he executed six landowners who, on their own, owned almost all the African lands.

Not all medium or small farms disappeared during the empire. Several remained for a long time, some even until the end of the Roman era, especially in marginal territories, as I have already said for our area of Bolgheri (see here and here).

The large estates, however, came to occupy a large part of the Italian peninsula. They were so large that it was less and less convenient to invest in specialized agriculture, such as viticulture. Animal farming became prevalent because it was inexpensive and requiring little labor. Thus, abandoned and shapeless landscapes spread, called saltus, which also appear in the pictorial landscapes of the time.

Initially, the saltus expanded to the detriment of the natural landscape of forests, destroyed by fire or by usurping public lands. During the Empire it expanded above all at the expense of the agricultural landscape and became increasingly perfectly superimposable on large landed properties. Only here and there was it interrupted by small worked plots, for the use of guardians and shepherds or the new figure of the colonus (of which I will tell later).

Palladius, in the fourth century AD, denounced those rich who built huge villae and gardens, neglecting agriculture or transforming fertile fields into pastures. He wrote that strange animals are raised only to feed the luxury of a few (such as peacocks, pigeons, thrushes, quails, …), while more and more hungry people flee desperately from the fields and pour into the city.

In the late Empire, the agriculture declined also due to excessive taxation, military despotism and anarchy. The barbarian invasions did the rest.

Our ancient colleagues.: the winegrowers

The agriculture of the origins, of subsistence, was managed by the owner and his family, such as Cincinnatus or Atilius Regolus described above. Over time, the villa was born, that is, the farm for profit. Cato is the first to describe it in his work De agri culture (160 BC). He wrote his work with the intention of providing practical advice to the (rich) farmers to grow their business, a sort of manual that proposes a managerial model to follow.

According to Cato, the vineyard is the most important and most profitable crop, so it must occupy an important part of the company. The ideal size for him is one hundred jugeri (just over 25 hectares). Only later will the large latifundium be born. However, we must not compare it to a vineyard of today with the same size, because Roman viticulture was always promiscuous. The vines rows were alternated with the cultivation of wheat or other cereals, as will remain common in Italy until the twentieth century (see the picture).

Cato says that, for his ideal winery of 100 jugeri, it takes 16 people to work. To manage it there was the vilicus (the factor), which is responsible for the direction of all agricultural work and administration, assisted by his wife, the vilica.

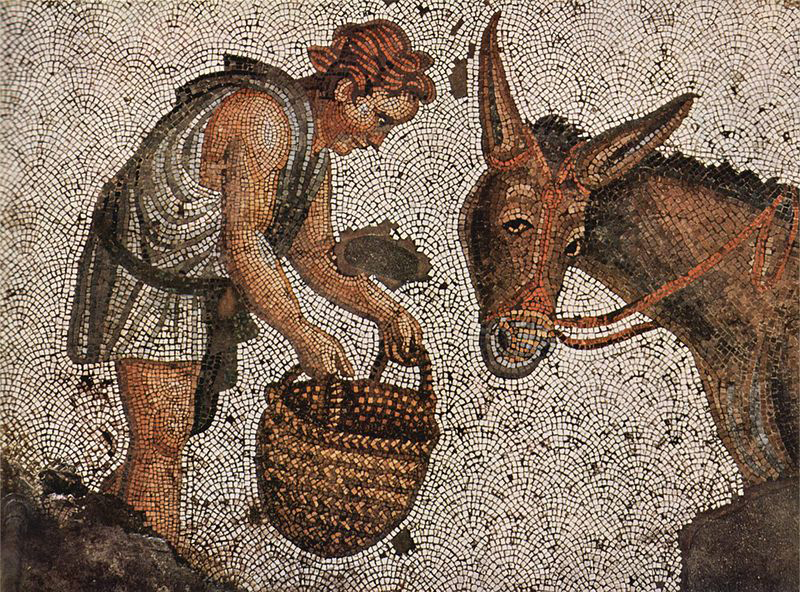

Below them, there were 10 generic workers (operarii), plus four skilled. The latter included a bubulcus (the cowboy, guardian and driver of the oxen), a subulcum (the helper of the bubulcus) and an asinarius (who took care of the donkeys). To plow and tow the carts, it takes two oxen and three donkeys, two of which for the carts and one for the olive oil millstone, with the equipment. The last skilled worker was the salictarius. He was the one who took care of the willows, whose branches were of multiple utility: the thinner ones were used to tie vines and other plants. The thicker ones were used to make baskets, mats and more.

Were they free or slaves? We know that the Roman villae were based above all on slave labor, yet Cato always writes of operarii, workers, never servants or slaves. However, the farms grew and expanded with the labor od slaves, especially starting from the Samnite and Punic wars. For a long time, prisoners of war were the main workers in agriculture. After Cato times, the figure of the ergastularius, appaeared; he was the guardian of slaves and servants. He controlled them and locked them in the evening so that they could not escape. We can console us to think that, sometimes, Roman slaves were able to redeem themselves as freedmen and even make social ascents, such as Palaemon or Acilio Sthenelo. However, it was unlikely that they were the unfortunate workers of the countryside. It was much easier for those who lived in close contact with their masters, managing to win their affection or respect. For example, the young Palaemon, accompanying his mistress’s son to school, had managed to demonstrate great intellectual gifts. The kind-hearted woman thus gave him the freedom and the opportunity to study.

In the large villas, sometimes rich until the squandering, the number of employees and their specialization increased exponentially. Here are some examples: vinitor (the winemaker, who took care of the vineyard in a specific way, in these large properties), putator (the pruning expert), frondator (who pruned the vines or other plants), fossor (the digger, this word was also used as a synonym of fool), pastinator (the worker who hoed the vineyard), vindemiator (the grape harvester), arator (the generic plower), germiniseca (the one who cut the small shoots in the gardens and in the vineyards), strictor (the olive picker from the branches), legulejus (the one who pick the olives fallen on the ground), saltuarius (the lumberjack), topiarii (the gardeners), mellarii (they dealt with bees and honey production ) and many others.

Columella even recommends that everyone, depending on the job, have certain physical characteristics. For example, the cowboy must have a big voice and body, the plower must be tall in stature, the vintner must have strong arms, the shepherd must be diligent and frugal, etc. However, it is a pleasure for us to discover that Columella stresses that slaves should be treated with familiarity and respect, even in their professional role. In fact, he writes that they must be consulted in the job choices. Unfortunately, it wasn’t the norm.

Let’s not forget also the free men, as mentioned above, who had to lend themselves to servile work (nexus) to pay their debts. There were also free and paid workers, prevalent in territories where different social relationships had been established. An example in this sense was our ancient northern Etruria, as I have already told here. Finally, the plots of a large estate could also be rented to free farmers, who cultivated it with their family and their slaves.

During the empire, the slave system went into crisis: there was no more expansion and the continuous supply of prisoners of war stopped. To deal with the shortage of manpower, the so-called colonus figure was born from the third century. A.D., a sort of preview of the medieval serfdom.

The term colonus means always farmer in Latin, but in that period it began to take on a particular meaning. Officially he was not a slave but a renter, but he had a relationship that was of the exclusive benefit of the wealthy owners. He was bound to the plot assigned to him by the landlord, so he could not leave at his leisure. He owed give almost all the production to the owner, except for what was strictly necessary to live, as well as having to carry out corvees in the manor fields. The final mockery was that he also had to pay taxes.

They were coloni by birth, or ex-slaves, or small landowners who “preferred” to renounce their independence because they were oppressed by debt and tax. There were also those who become colonus by conviction, for various crimes such as tax evasion or bankruptcy. This condition could only end with the choice to enter the army or clergy or through the temporal extinction of the crime. In the Justinian period, it was practically impossible to free oneself: one could only get out of it by managing to buy the land or becoming a bishop (!). Someone naturally tried to run away, like slaves did, with the risk of being severely punished by the master, even with death. Those who managed to escape could only become outlaw in the woods or hide in the crowds of the cities, or they had to put themselves under the protection of another lord.

(… continued…)

[alert style=”warning”]Roman units of measurement for agricultural areas:

Agricultural areas were mainly expressed with jugerum (plural: jugeri), about 2553 m2, more or less ¼ hectare (which, I remember, is 10,000 m2). The basic unit was the actus quadratus, half of the jugerum.[/alert]

Bibliography:

Interventi di bonifica agraria nell’Italia romana, a cura di Lorenzo Quilici e Stefania Quilici Gigli, ed. L’Erma di Bretchneider, 1995.

Storia dell’agricoltura italiana nell’età antica. Italia Romana. A cura di Gaetano Forni e Arnaldo Marcone, Edizioni Polistampa, 2002.

Luigi Manzi, 1883, “La viticoltura e l’enologia presso i Romani”.

Dalmasso e Marescalchi, 1931-1933-1937, “Storia della vite e del vino in Italia”.

Emilio Sereni, 1961, “Storia del paesaggio agrario italiano”.

Paolo Braconi, “Vinea nostra. La via romana alla viticoltura”.

Paolo Braconi, “Catone e la viticoltura intensiva”.

Paolo Braconi, “In vineis arbustisque. Il concetto di vigneto in epoca Romana.

Paolo Braconi, “L’albero della vite: riflessioni su un matrimonio interrotto”.

Attilio Scienza, “Quando le cattedrali erano bianche”, Quaderni monotematici della rivista mantovagricoltura, il Grappello Ruberti nella storia della viticoltura mantovana.

Attilio Scienza et al., Atti del Convegno “Origini della viticoltura”, 2010.

Cornelia Cogrossi, “Il vino nel «Corpus iuris» e nei glossatori”. In: La civiltà del vino. Fonti, temi e produzioni vitivinicole dal Medioevo al Novecento. Atti del convegno (Monticelli Brusati, Antica Fratta, 5-6 ottobre 2001). Centro culturale artistico di Franciacorta e del Sebino, Brescia, pp. 499-531.

M. R. Caroselli, “Terra e produzione agraria in Italia nell’Evo Antico”.

Jesper Carlsen, “Landuse in the Roman Empire”, ed. L’Erma di Bretschneider, 1994.