Continued from here

Let’s enter into the detail of the wine production of the Roman era.

The oenological practices

In the first place, among the oenological practices, we must put the blend, in which a good part of the art of the good cellar man of all times lies. For example, Pliny mentions the Ligurians and the inhabitants of the Po area as used to blend sour wines with others that are lighter. Marseille wines are cited as excellent blending wines, because they are too intense to be consumed alone.

To improve poor wines, the less invasive practice was to aging them on the lees of a good wine. For example, the wine of Sorrento was put in dolii with the lees of the precious Falerno, to give it more flavor. At the time, they kept the quality lees by drying them in the oven, in loaves. The addition of lees was also a classic technique of the past to overcome the fermentation stops, even if (of course) they did not know they were inoculating with yeasts.

They had found a series of substances to be added to the wine with the aim of improving, especially for the production of the large amount of medium-low quality wines. As I told here, at that time there was a tendency to produce a lot of grapes, with the consequence of musts or wines which were poor of some elements or with more or less pronounced defects. Several of these corrections will remain at the basis of modern oenology, with the difference (not secondary) that today purified substances are used. All the toxic ones have also been eliminated. However, today as in the Roman era, the best wines (which derive from balanced grapes) do not need it.

A common addition was the cooked must, which was the “sugar” of the time (along with honey). It was obtained from overripe grape must which was concentrated by a slow boiling. Thus, it formed a very sugary, dark liquid, with a more or less caramelized taste and rich in aromas. During cooking, it also was possible the adding of fruits or flavoring herbs. In wine production, the cooked must was added to fermenting must to increase the sugar component of low quality grapes. Today, I remember that it is allowed to add concentrated and rectified must or sugar (the latter is not allowed in Italy). The cooked must could also be added to the finished wine and, in this case, they produced the so called “cooked wine”. The use of cooked must remained for all the following centuries in Italy, especially in the center and south. However, the production of cooked must in Roman times was harmful to health, because it was mainly boiled in lead pots. During boiling, the lead diacetate (lead salt of acetic acid) is formed which has a sweet taste, also called Saturn’s sugar, saccharum Saturni (Saturn was the alchemical symbol of the lead). Its ingestion, like other forms of metal assimilation, can cause serious problems of chronic toxicity. It includes mental damage, the alteration of various organs and blood. Some scholars have hypothesized that certain forms of madness attributed to some Roman emperors could be symptoms of the saturnism.

They often added dried oak galls, outgrowths that form on the plant following the attack of parasites, the gall wasps (the Cynipidae, Hymenoptera insects). The galls have been used for millennia in the wine production because they contain a high percentage of tannins. These substances occur naturally in grapes and they are important components of wine, but they can be lacking in low quality products. Today, the galls are no longer added but purified tannins, as well as those obtained from oak or chestnut wood, from exotic essences, from grape seeds and grape skins. The tannins give a slightly bitter taste, so they must be carefully dosed, but they have several positive effects on the wine: they improve the structure and the body, they have a certain protective action (for example, they protect against the laccase, a deleterious enzyme for wine, which can be found in grapes attacked by gray mold), they help to stabilize the color, …

The addition of other vegetal elements also had a positive effect thanks to the contribution of tannins, such as olive stones or black or white hellebore (which contains gallic acid). At the time, it was thought that these plants had preservative effects on wine and that they were beneficial to health. On the contrary, the white hellebore contains a highly toxic hallucinogen. Yet, its use is often mentioned in antiquity, to enlighten the mind according to Petronius Arbiter (in the Satyricon) or as a remedy for madness for Horace (Third Satire, Book II) or against epilepsy. The black hellebore, on the other hand, is less harmful.

Pliny says that in Africa it was customary to add gypsum to wine, which was then eliminated by sedimentation. Adding plaster is a traditional practice commonly used until recently. It was typical of very hot areas, such as southern Italy and Spain. The gypsum was often scattered directly over the grapes, during the transport or during the pressing phase. This addition (remember that gypsum is calcium sulphate) has an acidifying action, with the secondary effect of reviving the color and clarifying the wine. In fact, the lack of acidity is a problem that can often occur in grapes produced in hot climates. The gypsum also slowly develops sulfuric acid in the wine, so it also has a light preservative action. However, it leads to an accumulation of sulphates, which are toxic above certain quantities. Today it is no longer used. Another product used as an acidifier in Roman and modern times was the alum (double sulphate of aluminum and potassium with 12 molecules of crystallization water), also no longer used.

On the contrary, to remove a too high acidity (a problem especially of grapes from cooler climates or not well ripened), they added marble powder or lime. Both of them bring calcium carbonate to wine, a substance used for millennia as a wine deacidifier. It is still used today, it is the cheapest, but it involves several problems such as the release of an excessive amount of carbon dioxide. Today the potassium tartrate (or other) is generally preferred.

Aggiungevano molti tipi di ceneri (incenso arso, cenere di radici di viti, gusci d’ostriche arse, cedro arso, …). Tutte queste sostanze hanno l’effetto di incrementare diversi sali. L’effetto è quello di aumentare l’estratto secco e, quindi, di dare più corpo al vino. Anche queste aggiunte sono state usate a lungo nel passato ma oggi sono pratiche illegali.

There are some substances that, for the Roman authors, gave a generic improvement of the wine: clay, milk, egg whites, wild pea flour, … I grouped them because today we know that they have the same function. They are the ancestors of various oenological practices still in use today, with a clarifying, refining and stabilizing function. They smooth out excess tannins and improve aromas. Today, the clay is still used but purified, like the bentonite or other similar products. The proteins of animal origin were used for a long time, such as the beaten egg white (the albumin), although today there is an obligation to indicate them on the label as allergens. After millennia of use, the milk is no longer used, but today there are still those who use an extract, the potassium caseinate. The flours of legumes, especially of peas, were used until not so long ago; today, vegetable protein extracts are used, which still derive mainly from these plants.

Other additions concerned the production of special wines, which were never blended with the normal ones. The addition of different herbs served for producing aromatized wines, such as those made with incense, roses, absinthe and much more.

Several wines imported from Greece (such as those from Chios, Kos or from Rhodes) were mixed with sea water, purified by decantation. The Romans took this use from the Greeks, but in smaller quantities. They believed that salting should be very precise, because the excess made the wine unpleasant and even harmful to health. Similar additions were also made until recently, with hydrochloric acid or table salt, but they are prohibited today. They were used to increase the chlorides in the wine, which may already be present a little (in different ways depending on the variety and the territory), with an effect of increasing the salinity and the dry extract (for a more full-bodied wine).

Another ingredient of some Roman wines was the vegetable resin. In addition to being used to coat all wine containers, it was sometimes added to the wine itself, for a particular product called resimato or impeciato wine. This practice also came from Greece, where a resin wine called Retsina is still produced today. Today only the resin of the Aleppo pine (Pinus halepensis L.) is used, but in ancient times many different essences were used, such as turpentine or terebinth (exudate of Pinus palustris L. and other Pinaceae), the mastic of the lentisk (Pistacia lentiscus L.), the resin derived from the seeds of ambrette or abelmosk (Abelmoschus moschatus L., an oriental Malvaceae), etc. The different types of resin were dissolved in olive oil and the must or wine was treated with it. The addition of resin seems to arise from the fact that it has a certain antiseptic action, which determines a protective action during fermentation, as well as a preservative action. However, it causes a strong aromatization of the wine, which is not appreciated by everyone. Curiously, I also found the resin in more recent oenological texts: the resinous smell is reported among the olfactory defects of wine in the late 19th-early 20th century. The professor Antonio Sannino wrote that it is frequently found in Trentino wines, due to the use of vats made with larch or fir wood.

The oenological practices were born to improve production but, over time, with the growth of the sector and the economic interests, they also degenerated towards strong adulterations. Unscrupulous businessmen used grapes of very poor quality, which were then heavily corrected in the cellars. In particular, they tried to cover the defects with very intense flavoring treatments.

These excesses were recognized and criticized even by the Romans themselves. Several authors write that they do not appreciate certain excessive aromatization, which altered the taste of wine or they considered dangerous to health. However, these wines had a market among the less privileged classes. For example, Pliny writes that Provençal wines were completely altered by an intense smoking and the addition of too many herbs, among which he feared that there were also some harmful ones. He also tells about the use of adding aloe to wine, to alter color and flavor. Some authors sarcastically write that they drink the Sabinus wine more willingly than many others, even if it was not among the most prized, because at least it was genuine and not too counterfeit. Although there was this perception, they never created a legislation to regulate the sector and put a limit on the additions made to wines.

The wine aging

The aging of wines in Roman times (to age = vetustescere) was done with heat. It was made only for the best wines, which were decanted in amphorae, closed with cork and carefully sealed. After that, they were left under the sun or in warm rooms. These amphorae were found by the archeologists almost everywhere in Pompeii: in the atriums of the houses, under the arcades, in the attics, in the kitchens, in rooms specially heated with furnaces (hypocaustum), … After a certain period of this treatment, they were stored in the fresh cellars. These aged wines, according to ancient testimonies, could last a very long time and were considered among the most renowned wines.

How could the taste of these wines be? We can find an answer to this question by looking for the use of heat for aging in times closer to us.

There is a wine that is still produced today with a system that closely resembles the Roman one. This is the Madeira, produced in an archipelago of Portugal, located off the northwest coast of Africa. The wine is added with sugar cane alcohol and then treated with the heat (around 50°C) for several months, in containers kept in rooms heated by stoves or left under the sun. This tradition of the heat use does not seem to derive from the memory of the ancient Roman use. The official history of Madeira wines tells that it was a recent rediscovery, which dates back to the 16th – 17th centuries. In this period the wine of the island began to be transported frequently by sea and they noticed that it matured remarkably when it crossed the equator twice. However, this wine has strong oxidative notes and is very stable, capable of very long aging.

Can we hypothesize that the aged wines of the Romans were similar to Madeira? The production is very similar. It is possible, but we will never be sure.

However, the use of heat was not completely forgotten after the ancient times. It continued to be mentioned in the agrarian texts of the following centuries, from the Late Middle Ages onwards, but we do not know if it was still used or not. For examples, Andrea Bacci (“Natural History of Wines”, 1596) writes that, in his day, wine was produced in a much simpler way than the accurate systems of ancient times, of which only a vague idea remained. However, we cannot exclude a priori that this technique was not yet used by someone.

However, there was a great return of the heat use for the wine aging from the second half of the nineteenth century and a part of nineteenth century. It was stimulated by the intense studies of the time on the nature of fermentation (see here), which led to Louis Pasteur’s important discoveries on the role of microorganisms in wine, and of oxygen in aging. Thanks to Pasteur, the pasteurization was born, a moderate heat treatment of short duration, used for the wine preservation. So, the idea of using heat for aging also returned. In particular, there was a very high interest in finding much faster and cheaper ways of wine aging, compared to the long times and high costs of the passage in wooden barrels.

The heat has a preservative effect because it eliminates the microorganisms and proteins (enzymes) that can cause the wine to deteriorate. There is also an aging effect (also favored by the high temperature) adding a (more or less) controlled exposure to oxygen. I remember that at the base of wine aging there is always an oxidation process. When it is very strong, it origins wines with a clearly oxidized taste. If minimal, it leads to finer and more elegant transformations.

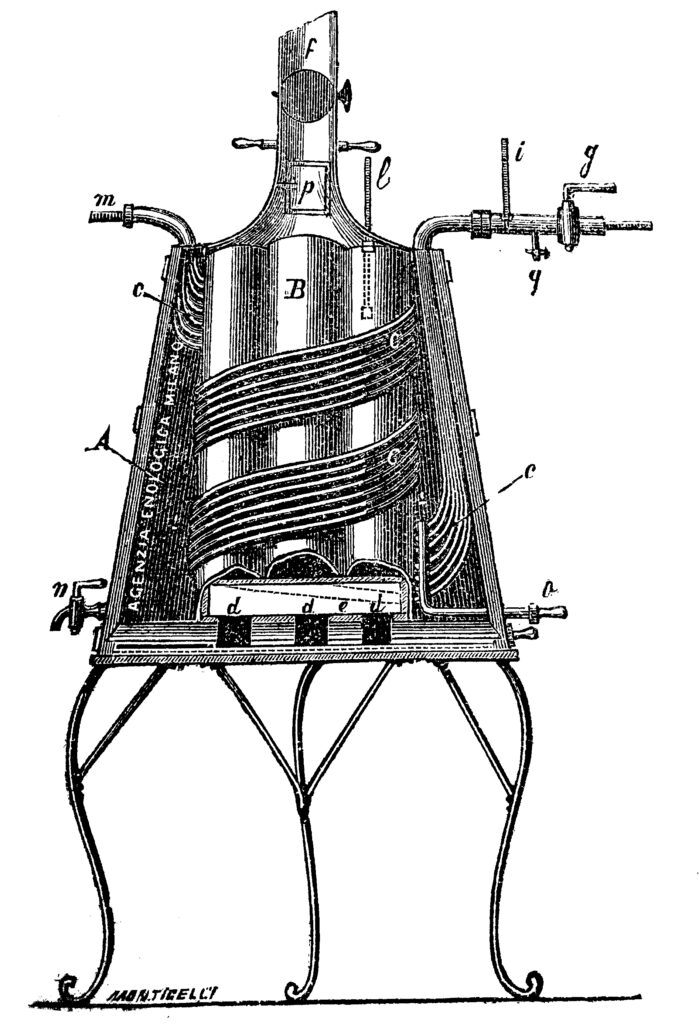

There were numerous studies that tried to define the practices for an optimal fast aging, defining the heat cycles, the temperatures (betwen 40° and 80°C) and the treatment times. It was important to avoid altering the taste of the wine with a “cooked” aroma. It was demonstrated, as the ancient Romans already knew, that this procedure was feasible only with wines of high alcohol content, of a certain power and good acidity, while the less intense ones were completely ruined. The Romans were mentioned only briefly, but similar systems were used, such as stoves for heating the rooms or for the bain-marie of the bottles, as well as exposure to the sun. There was also the creation of machineries for the continuous heating of wine, called “enotermo” in Italian, designed to treat even very consistent productions. They also studied systems that provided for the passage of electric currents in wine, a practice called “electrification”, but they were abandoned quite soon. At the end of all these treatments, the wine was stored for a few months in the cellar at fresh temperatures.

There was also a system of exposure to the sun, that was cheapest and least technological. It was made in clear glass containers, bottles or (more often) demijohns, not completely filled and well corked, left under the sun for some months. At the time, great importance was attached to the use of transparent containers because the antimicrobial action of sunlight on wine. We actually know that UV rays can have a sterilizing action, but also that they pass only minimally through the glass. The sun light has an effect of color altering.

Even if these heat aging systems were used for some time, the results were always quite controversial. However, from the texts of the authors of the time, it is not easy to understand what they meant by “good aging”. For example, prof. Arturo Marescalchi made some tests with a wine (made with Freisa and Barbera varieties) in 1894, leaving some bottles in the July sun for 12 days. Some bottles were exposed to light, others covered with a black cloth and some, as control, were stored in the cellar. According to him, the best was the wine exposed to heat and light, which had become very old, with an orange color that today we would not considered so good. Some authors positively described these aged wine as similar to Madeira wines. However, many other authors disliked a so intense oxidation, because it standardizes the wines.

Professor Garoglio, in the 60s of the twentieth century, wrote that the success of heat aging was questionable and very casual. The results were quite appreciable in some cases, totally disastrous in others. In his time, the heat aging was still in use, but it was going to disappear. From the 1960s – 1970s, the use of aging in wooden barrels returned to growth, also thanks to the renewed economic capacity of the wineries. The pasteurization for conservation purposes was also increasingly abandoned for wine, while it remained for other foods (such as milk, beer and fruit juices). This treatment is yet permitted today. Perhaps there are those who use it, but without too much publicity, because it is not considered a very qualitative practice.

The poors’ wines

In ancient times nothing was wasted and wines of extremely low quality were produced for the poorest and the slaves. These practices of frugal peasant life will remain in use for centuries.

In ancient times nothing was wasted and wines of extremely low quality were produced for the poorest and the slaves. These practices of frugal peasant life will remain in use for centuries.

For example, the protropo wine was made with the must that Columella calls lissivo, that is the one that flowed by the weight of the grapes that were gradually accumulated in the pressing vat. Today, it would be like making wine with that liquid that remains at the bottom of the grape crates (especially if they have been a little too mistreated).

They produced wine also pressing used marc or lees, that were dunked in water for some days. These wines were called vini secondi (second wines) or lora. Cato calls the wine made with used lees vin fecato. These wines were very light and cheap, often used for servants and slaves. The practice of marc or lees wines has remained common over the centuries. Their production and sale, for consumption, was definitively prohibited in Italy in 1925 (royal decree n.2033 of 15/10/1925), because they were at the origin of many frauds (they were often saled as grape wines). In this period, they were still called second wines (vini secondi, in Italian), as in Roman era.

Is it possible to drink similar wines?!?!

Consider that, until not so many decades ago, drinking quality wine for pleasure, as we do today, was only a privilege for the rich. All the other people drank wines that ranged from moderate to very poor quality.

However, in the past, even the worst wine had a significance. It added extra calories to meals that were often too light, as well as giving a little more flavor and a light alcoholic vivacity. Also, these everyday wines were considered healthier than drinking just water. Today we know why: even a low alcohol content protected from microbiological contaminations, which instead were very frequent and risky drinking water.

We talked about many wines produced in Roman times, with techniques that have remained almost until today. Some wines were very good, others not so bad, some heavily adulterated, others very very light. Whether they drank for pleasure, for health or for any other reason, we close the question with the Roman toast. Instead of our “cheers”, they said:

“Bene vos” or “Bene nos” or “Bene te” or “Bene me”, …

“Bene vos” “Bene te” (I wish you the best), “Bene nos” (I wish us the best), “Bene me” (I wish the best to myself), …

BIBLIOGRAPHY

“L’agricoltura di Lucio Giunio Moderato Columella” volgarizzata da Benedetto del Bene, con annotazioni adattate alla moderna agricoltura e con cenni sugli studi agrari d’Italia del cav. Ignazio Cantù, Milano, dalla Tipografia di Giovanni Silvestri, 1850.

“De re rustica”, Lucio Giunio Moderato Columella (60-65 d.C.), tradotto da Giangirolamo Pagani, 1846

“Interventi di bonifica agraria nell’Italia romana”, a cura di Lorenzo Quilici e Stefania Quilici Gigli, ed. L’Erma di Bretchneider, 1995.

“Il vino nel «Corpus iuris» e nei glossatori”, Cornelia Cogrossi, (2003) In: La civiltà del vino. Fonti, temi e produzioni vitivinicole dal Medioevo al Novecento. Atti del convegno (Monticelli Brusati, Antica Fratta, 5-6 ottobre 2001). Centro culturale artistico di Franciacorta e del Sebino, Brescia, pp. 499-531.

“Storia dell’agricoltura italiana: l’età antica. Italia Romana” a cura di Gaetano Forni e Arnaldo Marcone, Edizioni Polistampa, 2002

“Terra e produzione agraria in Italia nell’Evo Antico”, M. R. Caroselli.

“Origini della viticoltura”, Attilio Scienza et al., Atti del Convegno, 2010.

“La viticoltura e l’enologia presso i Romani”, Luigi Manzi, 1883.

“Storia della vite e del vino in Italia”, Dalmasso e Marescalchi, 1931-1933-1937.

“Storia del paesaggio agrario italiano”, Emilio Sereni, 1961.

“Il vino nella storia”, Enrico Guagnini, 1981.

Hugh Johnson, “Il vino, storia, tradizioni, cultura”, 1991

Tim Unwin, “Storia del Vino “, 1993

Antonio Saltini, “Storia delle pratiche di cantina, Enologia antica, enologia moderna, un solo vino o bevande incomparabili?”, Rivista di Storia dell’Agricoltura a. XXXVIII, n. 1, giugno 1998

E. Chioffi, “Anfore, archeologia marina”, Egittologia.net

“Storia dell’agricoltura italiana: l’età antica. Italia Romana” a cura di Gaetano Forni e Arnaldo Marcone, Edizioni Polistampa, 2002

“Terra e produzione agraria in Italia nell’Evo Antico”, M. R. Caroselli.

“Il vino da pasto e da commercio”, di Ottavio Ottavi, 1875, Tipologia Sociale del Monferrato, Casale.

“Trattato completo di enologia”, di Antonio Sannino, 1914, Stabilimento di Arti Grafiche, Conegliano.

“La nuova enologia” di Pier Giovanni Garoglio, 1963, Istituto d’Industrie Agrarie, Firenze.