I told you about the taste of Roman wine (see here). Then we walked for a long time in the vineyards of the time (see here, here, here, here here, here). Finally, we enter the cellar.

[one_second][info_box title=”” image=”” animate=””] The wine consumption in Rome: sobriety or vice?

In our imagination we often associate Roman wine with banquets, with drunks in togas who puked their brains, due to many films or other representations that exalt the vices of the ancient world.

In fact, it is true that wine was consumed a lot in Roman times, but generally in a sober way. The prevailing culture was that which, more or less, remained in Italy: the wine was drunk almost exclusively with meals and without exaggerating, always diluted with water (to dilute the high alcoholic strength of the time). The only exceptions, like today, were the parties, the banquets. The excesses of some rich people were certainly not the norm.

The vice of drunkenness, called temulentia (from temetum the oldest word for wine in Etruscan and Latin) was rather frowned upon socially. For example, Octavian often accused Mark Anthony of loving wine too much, using this weapon to discredit him politically. True or not, Anthony is remembered yet today as a drunkard.

However, there has been a great evolution over the centuries. In the most ancient times, the wine was not abundant, both because the production was still limited, and because of the more rigid climate (see here the climatic changes of the Roman era). the wine was a luxury item for the most ancient Romans, reserved almost exclusively for banquets, for social and religious events. Later and thanks to theproduction expansion, it will be introduced more and more in common meals. Seneca says that the ancestors usually allowed themselves a little wine only at the end of the meal and considered those who drank it during the meal as glutton.

The strict customs of ancient Rome forbade wine to women. Wine was associated with the loss of control, hence the risk of adultery on the part of the wife. In the time of Romulus, Egnatius Mecenius killed his wife with stick for drinking wine and was even praised for the “exemplary punishment”. Later in the history of Rome, women no longer risked their lives just for a little wine, but only a moderate consumption was socially accepted for the respectable ladies. For example, the judicial chronicles report the case of a woman who was fined by the judge, with the loss of her dowry, because she had secretly drunk more wine “than was deemed necessary for the health”.

The strict customs of ancient Rome forbade wine to women. Wine was associated with the loss of control, hence the risk of adultery on the part of the wife. In the time of Romulus, Egnatius Mecenius killed his wife with stick for drinking wine and was even praised for the “exemplary punishment”. Later in the history of Rome, women no longer risked their lives just for a little wine, but only a moderate consumption was socially accepted for the respectable ladies. For example, the judicial chronicles report the case of a woman who was fined by the judge, with the loss of her dowry, because she had secretly drunk more wine “than was deemed necessary for the health”.

Over time, however, the production of wine increased more and more, arriving at large productions of low quality wine for the masses and a small elite of refined wines for the rich, and the customs became less and less severe. The consumption of wine became common for all the meals. In the Satires of Varro (1st century BC), he jokes about the meal without wine, calling it “prandium caninum“, the dogs’ meal (who certainly do not drink wine).

Arriviamo quindi all’epoca Imperiale, con gli eccessi celebrati nei tanti film in toga, dei quali Plinio dice di vergognarsi anche dal riferire. Nei casi più estremi, si poteva arrivare ad infilarsi una penna in bocca per indurre il vomito e poter ricominciare a bere e a mangiare.

During banquets, which were not necessarily always unbridled, it was customary to toast to the Gods, friends, lovers or the powerful. There was also the use of the nomem bibere (drinking the name): drinking as many glasses as there were the letters of the name of the beloved or the powerful to whom the toast was dedicated.

Pliny also reports the custom of “drinking the crowns“, that is, lovers exchanged cups of wine with inside the petals of their crowns made of flowers and herbs. These vegetable wreaths, which became common at the banquets, were born from the belief that they would prevent drunkenness, by wearing them. Over time, they also became luxury items, made with the rarest and most fragrant flowers.

Among the many dark legends that circulated about Cleopatra, it is told of the time that, offended by Antony, she tried to poison him, offering him a cup of wine with the petals of her flower crown, which had been soaked in poison. At the last, however, she repented and stopped him before the fatal sip. Anyway, to teach a lesson to Antony, she made drinking the poisoned cup to a man sentenced to death, in front of him.

[/info_box][/one_second]

Our harvest is very close and it seems to me very appropriate to talk about winemaking again. I do it, however, by going to its origins, to the Roman era.

However, I do not want to tell you about the terracotta amphorae and other generalities that we all know well, for the umpteenth time, if not for quick hints. Instead, I really want to enter a cellar of the time, with the spirit of the wine producer, and understand their techniques, beyond myths and prejudices.

You will certainly have read of those who report, with perplexity, that they added many strange things during the vinification: sea water, milk, olive stones, marble dust, wild pea flour and more. In reality, these practices are not as absurd as they may seem, as I will explain you later. Indeed, they represent the first rudimentary approaches to the modern enology. In this period, in fact, various oenological practices were born that will be developed later, both for better and for worse, with even an excessive adulteration of the wines.

In general, we can say that the Romans had developed a technically accurate wine production at their peak, as you will see, even if some aspects are incomprehensible to us (especially due to the scarcity of information). We don’t forget also the objective limits of the time. Anyway, this production level will be lost in the early Middle Ages, with a marked deterioration in wine quality, and will only be regained after centuries, before the definitive leap towards the modern enology.

Light and shadow

At the moment of the peak, they produced different types of wine: still, sparkling, dry, sweet, raisin wine, … All these wines were good enough to be drunk without corrections, apart from the usual dilution with water (necessary to dilute the high alcoholic gradations of the time, due to harvesting of overripe grapes; it is, however, a natural system of conservation). In the even more ancient times, the production techniques were very primitive and the wines were so bad that they always had to be corrected at the time of service with herbs, spices and honey and more (see here), to make them drinkable. The honey sweetening will remain, but only for a particular “cocktail”, called mulsum, served as an aperitif. Herbal wines will also remain, for medicinal use or pleasure, but they were specific products.

Roman wine production has therefore evolved considerably over the centuries, starting from primitive systems. This development has depended by integrating the knowledge of the time (the Latin authors cite many references, overall of Greek texts, which we have not received), through an empirical experimentation, and a remarkable technological evolution of the instruments (about which I have already told here, speaking of Etruscans wine production). The most advanced Roman presses did not change until the 19th century.

The apex period is represented by the texts of Columella and Pliny the Elder (as we have already seen for the part of viticulture), in the second half of the 1st century. A.D. These texts describe an accurate wine production, without however granting us many details and explanations. They focus their attention above all on practices aimed at improving low-quality wines, the great mass of production. They also mention a small niche of wines of great value, for which, they write, any modification isn’t necessary during the winemaking.

In the following period, there will be only some technological evolutions, such as the invention of the densimeter (hydroscopium), a tool for evaluating the density of liquids. As far as we are concerned, it is used to measure the amount of sugar and alcohol in musts and wine (opposite, a drawing of a more modern hydrometer). It is mentioned for the first time by Synesius, in a letter written to his teacher Hypatia, at the turn of the IV-V century AD. However, it seems that the common use dates back to the sixth century, as the grammarian Priscian recounts. This and other knowledge will be lost in the following centuries. A similar instrument will be invented again at the beginning of the 17th century.

However, there are still several inexplicable aspects for us in the production of wine from the Roman era. One of the most striking is represented wines with incredibly long aging, even of hundreds of years, that are praised by some poets. Considering that even today it is not possible to have such long-lived wines (which remain drinkable and pleasant), they were probably just hyperbole or poetic licenses.

Some important passages of winemaking are totally omitted in the ancient texts. For example, the maceration of the skins is never described. This fact has misled some modern authors of wine history, making them write that only white wines were produced , at the time. In reality, the Latin authors speak of a wide range of colors. Pliny writes about white, fawn (orange wine?), red and black wine. Galen also adds pale red (pink?) and pale, which he describes as an intermediate tonality between white and fawn.

In any case, the Romans certainly laid the foundations of some oenological practices, as I will explain you, but they did not know why they did them or why they added certain substances to wine, having no chemical knowledge on the compositions of musts and the products they used. They could just appreciate the final results. The other insurmountable limit of the time was the absolute ignorance on fermentation, as well as on microbiological alterations of the wine.

So, they might be good at making some wines, but they were always at the mercy of luck and chance. If something went wrong, they could do nothing and, simply, they downgraded the wine. However, this productive fragility does not belong only to the Roman era, it will remain for a long time. These processes will begin to be understood (and managed) only after the Pasteur’s discoveries on the role of microorganisms in wine production, but we will have to wait until the second half of the nineteenth century.

Finally, let’s not forget that, as in every past era, different realities coexisted: the richest wineries equipped with the most advanced tools, those (of all sizes) managed by educated or otherwise expert people, up to the many farmers who continued to making wine in a very primitive way.

Some core concepts

The Romans had already reached a certain awareness regarding some key concepts of wine production, which will be rediscovered only centuries after the end of the ancient era.

First of all, there is the importance of cleaning. They certainly did not know of the existence of microorganisms, they did not have our sanitizing products, the running water in the cellars and many other things. But they had realized how important it was to clean everything properly. The care and perfect cleaning of each container and tool, before and after each use, is a “mania” for the Roman authors, since the most ancient times of Cato. This way of working will be recuperated, in modern times, only quite recently. The cleaning of the wine containers was facilitated by the internal coating, made with vegetable resin, renewed with each use after having thoroughly scraped the old layer. They also recommended carefully cleaning them of any residual odors. In a cellar in Stabiae (today Castellammare di Stabia, in Campania), found totally intact by the archaeologist Fiorelli at the end of the eighteenth century, the grape pressing room was covered on the floor and the walls with a material made of crushed bricks and slaked lime, up to about one meter and eighty in height, with the limit marked by a red line. Lime is the oldest way to sanitize walls subject to the humidity. Its alkalinity prevents the development of molds and other microorganisms.

They also understood the importance of temperature during the winemaking process. Columella recommends bringing the wine containers to hot or cold places, as needed, or to have anphoras in different positions. He writes that if you feel the temperature rise too much by touching the wine amphora, you will certainly not have a good vinification. Today we know that fermentation yeasts work well at certain temperatures. Especially too high temperatures can compromise the process. In a cellar in Pompeii, an ingenious system was found to cool wine amphorae. These were leaned against a clay cavity in which fresh water was made to flow. In the description of the production of sweet sparkling wines, we read that the amphorae were transferred at a certain point in cold water tanks (to stop fermentation and leave a sugary residue). As still today, the cold was an ally of the cellar men to favor the processes of sedimentation and then racking of wines. In Late Empire texts, the importance to have fresh cellars is emphasized. If this was not the case, it was necessary to take advantage of temperatures seasonal changes to make certain operations. The ancient authors often link certain oenologist practices to some constellations (or other) for this reason: it is not a question of astrology, but their way of indicating the most appropriate seasonal moment.

They also understood the risks of wine oxidation (for them a generic alteration). In fact, the authors write to avoid exposing the wine to the air, especially at high temperatures. In the description of each winemaking step, the authors insist a lot on always having the containers carefully covered internally with vegetable resins and well closed.

The cellar and the winemaking

The production of wine was not so different from that of any winery of the past, at least until the nineteenth century, except for the wine containers.

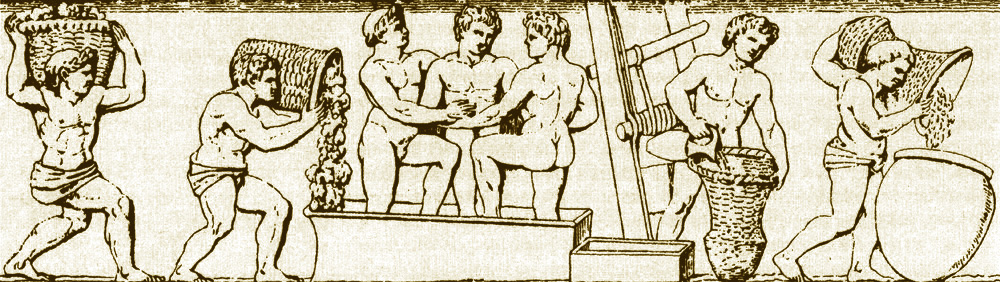

The grapes were pressed with feet in the “palmenti” (stone or masonry tanks). The pomace or the whole bunches (closed inside wicker baskets or other material) were pressed. As we know, the main winemaking vessels were large terracotta containers called dolii (dolium in the singular), covered internally with vegetable resin, partially or completely buried. Their oldest name was calpar, already no longer in use at the time of Varro (1st century BC). There were also closed masonry tanks, although less widespread.

What was the purpose of the internal covering with resin of wine amphoras? It was made by resins of vegetable origin, which are substances of different nature produced by numerous plants, sometimes following wounds or parasitic attacks, so they are often also natural antiseptic. They have been used for thousands of years, for the most diverse uses, before the introduction of the synthetic resins or other materials. Often, they are also aromatic and we don’t know how much this coating affected the taste of the wine or not. This coating certainly served to make these containers as inert as possible, as we try to do even today. The resin coating seals the porosity of the amphorae, against the risk of oxidation and makes them perfectly impermeable to liquids. It also guarantees a certain cleanliness, against the risk of microbiological contamination, since after each use the pots were carefully scraped from the old resin layer and re-coated.

They considered important to evaluate the foam, that forms on the liquid, to understand the good proceeding of the fermentation. In particular, they describe one of the most common alterations of wine until not so long ago, the “fioretta” (I was not able to try the word in English). They describe it as a clear film, like a spider’s web, on the surface of the wine. The altered wine became tasteless and flat, with a more or less intense aroma of vinegar. Above all, it happened for wines with a low alcohol content that remain too much in contact with oxygen. Now we know that it depends on the development of different species of aerobic bacteria.

After the fermentation, there was a period of aging on the lees. Then, they were poured into new containers, in the month of May. It was the moment to classify the quality of the product, through the tasting. The wine acidity was considered a very important parameter: if it was too low, it was not a good sign for the shelf life and quality of the wine (as we know even today).

The low-quality wine, or that to drink young, was usually placed in new dolii (so it was called vinum doliare), from where it was taken for the sale or the consumption, pouring it into jugs or other. The transport by land was made by a large leather wineskin, called culleus or uter vini, placed on a cart.

The best wine was put in amphorae and for this reason it was called vinum anphorariarum. This container was used for storing, aging and shipping. The amphorae were always covered inside with vegetable resins, carefully closed with corks which was sealed with resin, clay or plaster. They were identified by a nota, that is, a brush writing made directly on the amphora or on a parchment or a strip of leather. This old kind of label was called pittacium. The nota reported the wine type (for example, the abbreviation rubr. means red wine), the place of origin and the year in which it was stored. Especially from the 2nd century AD., the wine could also be stored and transported in wooden barrels (cupa), and it was called vinum de cupa. Pliny already describes them in the second half of the first century BC, as typical of the area of the Alps.

To move the liquids (must or wine) from one container to another, long siphons were used, or smaller transport containers (amphorae or other). In more rich cellars, as in one found in Stabia, the grape-crushing area had a sloping floor towards a drainage channel, where lead pipes (fistula) could be inserted to carry the wine into the fermentation dolii. The aulon sysetera was a glass instrument used to take small tasting samples from the wine containers, similar to the wine tester (or pipette) still used today.

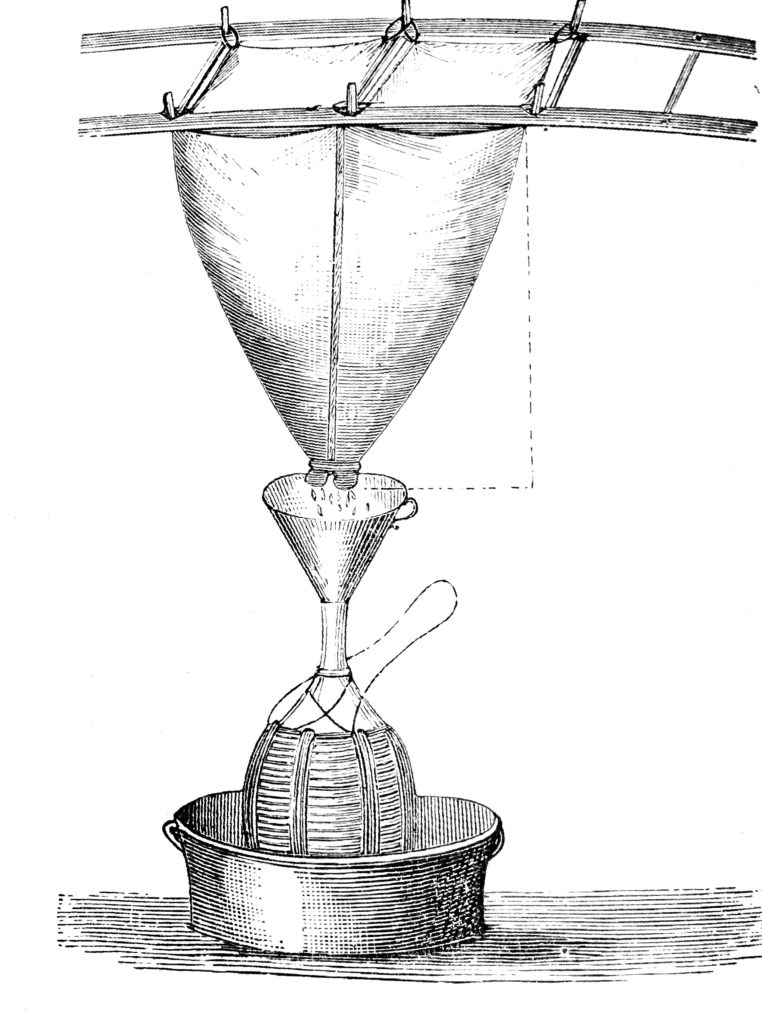

To eliminate sediments and lees, they used the system that has always been used in the cellars, i.e. the decanting after allowing the sediments to settle on the container bottom. For the cleaning and filtration of wines, the authors tell us of a colum or saccus vinarius, a basket or colander made of wicker, mat or rushes, in the shape of a cone (below, a similar nineteenth-century one).

CONTINUE … with the oenological practices.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

“De re rustica”, Lucio Giunio Moderato Columella (60-65 d.C.), tradotto da Giangirolamo Pagani, 1846

Luigi Manzi “La viticoltura e l’enologia presso i Romani”, 1883

Dalmasso e Marescalchi, “Storia della vite e del vino in Italia”, 1931-1933-1937

Emilio Sereni, “Storia del paesaggio agrario italiano”, 1961

Enrico Guagnini, “il vino nella storia”, 1981

Hugh Johnson, “Il vino, storia, tradizioni, cultura”, 1991

Tim Unwin, “Storia del Vino “, 1993

Antonio Saltini, “Storia delle pratiche di cantina, Enologia antica, enologia moderna, un solo vino o bevande incomparabili?”, Rivista di Storia dell’Agricoltura a. XXXVIII, n. 1, giugno 1998

E. Chioffi, “Anfore, archeologia marina”, Egittologia.net

“Interventi di bonifica agraria nell’Italia romana”, a cura d Lorenzo Quilici e Stefania Quilici Gigli, ed. L’Erma di Bretchneider, 1995.

“Storia dell’agricoltura italiana: l’età antica. Italia Romana” a cura di Gaetano Forni e Arnaldo Marcone, Edizioni Polistampa, 2002

“Terra e produzione agraria in Italia nell’Evo Antico”, M. R. Caroselli.