So far, I have spoken about the Roman era in our territory (here and here), about its wine production and European trade.

But, how was this wine?

How can we imagine the taste of Roman wines today?

First of all, let us remember that the Roman period was very long and with great changes. The wines of archaic Rome were certainly very similar to those of ancient Greece and the Etruscans. In those remote eras, limited production techniques produced wines with a “difficult” taste, the consumption of which always required the addition of spices, aromas, honey and so on (see here).

In Rome, however, there was a remarkable agronomic and technical evolution over the centuries, reaching a very different production situation, which we will try to understand.

[one_third][info_box title=”The Rural Latin writers” image=”” animate=””]

There are five fundamental works to learn about Ancient Roman viticulture and wine production, whose authors were called in the past the Rustici Latini (rustic, or rural, because they wrote about agriculture). These are Cato, Varro, Columella, Pliny and Palladius, which I will often quote in my next posts about Roman wine production.

Each of their works “photographs” a different historical moment in the long evolution of Roman agriculture (about thirteen centuries, for the Western Empire). Understanding a culture, an era, cannot be separated from its becoming, as rightly always Emilio Sereni pointed out: the agricultural landscape is not static but extremely subjected to a perennial historical elaboration.

Less specific aids, more sporadic but no less interesting, come from other non-sectoral authors. These are historians, geographers, poets, etc., such as Strabo, Galen, Cicero, Virgil, Horace and many others.

Unfortunately, we also know that only a minimal part of ancient literature has arrived. For example, Varro, in the introduction to his De re rustica, lists fifty agronomic works in Greek to which he refers, now lost.

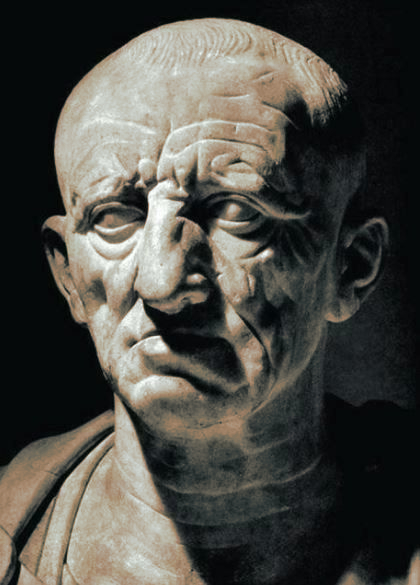

THE MANAGER: Cato (Marcus Porcius Cato, known as Censorius, the Censor, Tusculum 234- Rome 149 BC), military and politician, wrote his work De agri cultura (or De re rustica) in the Republican era, published in 160 BC. This is an unstructured series of practical advice addressed to the pater familias, the agricultural owner, above all to push him to move from an ancient and subsistence agriculture to the more profitable one, with economic purposes. We are at the dawn of the then nascent Roman villa, the great farms of the times. Cato wants to re-propose ancient values. His model of the true “civis Romanus” (the Roman citizen) is the “vir bonus colendi peritus“, the honest and good farmer, who takes the sword in times of need. The style is meager, a Latin with much archaisms.

THE MANAGER: Cato (Marcus Porcius Cato, known as Censorius, the Censor, Tusculum 234- Rome 149 BC), military and politician, wrote his work De agri cultura (or De re rustica) in the Republican era, published in 160 BC. This is an unstructured series of practical advice addressed to the pater familias, the agricultural owner, above all to push him to move from an ancient and subsistence agriculture to the more profitable one, with economic purposes. We are at the dawn of the then nascent Roman villa, the great farms of the times. Cato wants to re-propose ancient values. His model of the true “civis Romanus” (the Roman citizen) is the “vir bonus colendi peritus“, the honest and good farmer, who takes the sword in times of need. The style is meager, a Latin with much archaisms.

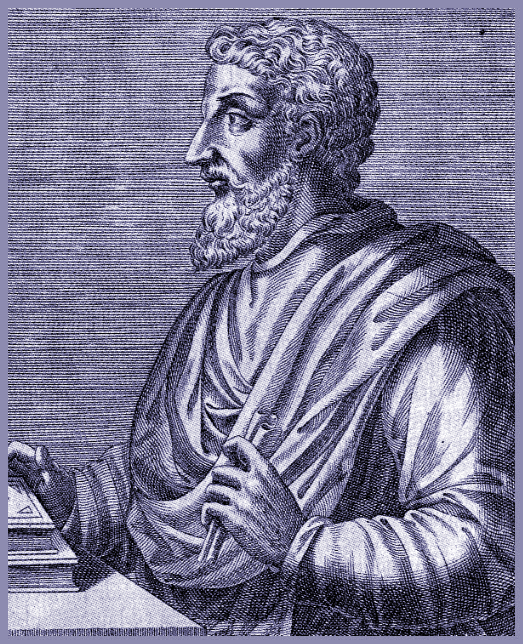

THE INTELLECTUAL: About 120 years later, we have the testimony of Varro, Marcus Terentius Varro, a politician and a scholar (Rieti, 116 BC – Rome, 27 BC). He published his work De re rustica in 32 BC. It is a time of crisis for agriculture, which follows the period of civil wars. At its time the agricultural villa has now evolved towards ever larger estates, to the detriment of small farmers. It has also become a place of pleasure, of refined leisure and rest for the rich owners. The work is in the form of a dialogue between the same author, his wife and friends. The recipients are certainly not the small farmers but the large landowners, with many lands and vast herds, lovers of profit and luxury. He encourages the recovery of the fathers’ values, the mos maiorum. With noble nostalgia, he also aestheticizes an idealized country life, simpler and more fulfilling than the city one, full of vice and corruption.

THE INTELLECTUAL: About 120 years later, we have the testimony of Varro, Marcus Terentius Varro, a politician and a scholar (Rieti, 116 BC – Rome, 27 BC). He published his work De re rustica in 32 BC. It is a time of crisis for agriculture, which follows the period of civil wars. At its time the agricultural villa has now evolved towards ever larger estates, to the detriment of small farmers. It has also become a place of pleasure, of refined leisure and rest for the rich owners. The work is in the form of a dialogue between the same author, his wife and friends. The recipients are certainly not the small farmers but the large landowners, with many lands and vast herds, lovers of profit and luxury. He encourages the recovery of the fathers’ values, the mos maiorum. With noble nostalgia, he also aestheticizes an idealized country life, simpler and more fulfilling than the city one, full of vice and corruption.

THE AGRONOMIST: we make a jump of about 90 years and we come to the treatise De re rustica by Columella (Lucius Iunius Moderatus Columella, Cadiz 4 d.C. – 70 AD), military tribune and then farmer in his properties in Lazio. It was published between 60 and 65 AD, in Imperial Times. It is considered the first true agronomic treatise in history because its accuracy and completeness . Unlike all the others, it emerges that the writer really took care of the management and works of a farm. We can find the apex of the evolution of Roman agricultural techniques in this work, that has remained unsurpassed for centuries. It is incredibly detailed and precise for viticultural practices. It includes more fragmentary suggestions for the wine-making parts. According to Columella, the farmer must personally take care of the management of his company, adequately training himself by valid texts. Given the mentality of the time, it is striking his exhortation to treat slaves with humanity and familiarity, consulting them also in work choices.

THE AGRONOMIST: we make a jump of about 90 years and we come to the treatise De re rustica by Columella (Lucius Iunius Moderatus Columella, Cadiz 4 d.C. – 70 AD), military tribune and then farmer in his properties in Lazio. It was published between 60 and 65 AD, in Imperial Times. It is considered the first true agronomic treatise in history because its accuracy and completeness . Unlike all the others, it emerges that the writer really took care of the management and works of a farm. We can find the apex of the evolution of Roman agricultural techniques in this work, that has remained unsurpassed for centuries. It is incredibly detailed and precise for viticultural practices. It includes more fragmentary suggestions for the wine-making parts. According to Columella, the farmer must personally take care of the management of his company, adequately training himself by valid texts. Given the mentality of the time, it is striking his exhortation to treat slaves with humanity and familiarity, consulting them also in work choices.

THE ENCYCLOPEDIC: contemporary of Columella, Pliny (Pliny the Elder, Gaius Plinius Secundus, Como 23- Stabia 79 AD) gave a remarkable contribution with his masterpiece Naturalis Historia, written in 73 AD. It is a general and very vast compendium on the knowledge of the epoch that ranges from geography, to anthropology, to botany, etc. Sometimes, however, he let himself get carried away by the taste of fantastic and emphasis. Pliny died in one of the greatest catastrophes recorded in history, the eruption of Vesuvius in 79. Driven by his scientific curiosity to observe the phenomenon, he died from poisonous fumes. His work is important for wine history because it provides various indications on the viticulture and wine production of his era, the list of many varieties of grapes and wines, as well as on the diffusion of viticulture in Europe.

THE ENCYCLOPEDIC: contemporary of Columella, Pliny (Pliny the Elder, Gaius Plinius Secundus, Como 23- Stabia 79 AD) gave a remarkable contribution with his masterpiece Naturalis Historia, written in 73 AD. It is a general and very vast compendium on the knowledge of the epoch that ranges from geography, to anthropology, to botany, etc. Sometimes, however, he let himself get carried away by the taste of fantastic and emphasis. Pliny died in one of the greatest catastrophes recorded in history, the eruption of Vesuvius in 79. Driven by his scientific curiosity to observe the phenomenon, he died from poisonous fumes. His work is important for wine history because it provides various indications on the viticulture and wine production of his era, the list of many varieties of grapes and wines, as well as on the diffusion of viticulture in Europe.

THE COUNTRY GENTLEMAN: we make a leap of about two hundred years and we arrive at the last great author of agriculture of the Latin era, in the Late Empire (IV century AD), the Palladius (Rutilius Taurus Aemilianus Palladius). He was a rich and noble landowner, author of Opus agriculturae or De re rustica, which is a sort of rural calendar, in which he explains the agricultural work for the different periods of the year. In reality it does not make technical evolutions that go beyond Columella. However, his historical testimony is very interesting, as well as from a linguistic point of view, with a Latin mixed with vernacular words.

THE COUNTRY GENTLEMAN: we make a leap of about two hundred years and we arrive at the last great author of agriculture of the Latin era, in the Late Empire (IV century AD), the Palladius (Rutilius Taurus Aemilianus Palladius). He was a rich and noble landowner, author of Opus agriculturae or De re rustica, which is a sort of rural calendar, in which he explains the agricultural work for the different periods of the year. In reality it does not make technical evolutions that go beyond Columella. However, his historical testimony is very interesting, as well as from a linguistic point of view, with a Latin mixed with vernacular words.

There are other classical authors, such as Cassianus Bassus (the Geoponics, 6th century AD) from the Eastern Roman Empire. They are considered less interesting because they have no original contributions. Their works are often collection of quotes from the previous authors. After Palladio, in the West, there was a void of about eight centuries, up to the first and only medieval agronomic text considered significant, written in 1304 by the Bolognese Pietro De’ Crescenzi (he draws a lot from the Rural Latin authors too).

Columella’s work, however, will remain the reference agricultural text for the West at least until the 18th century.

[/info_box][/one_third]

Unlike the Etruscans, we have many direct testimonies of this era (see the box on the side). We can therefore say that we know a lot about the wines of Rome, but also that we do not know everything. In fact, these writings are incredibly detailed in some respects (see for example Columella, with his long and meticulous descriptions about vines propagation) but also incredibly incomplete on others, especially about cellar practices. About the description of grapes and wines, we have just lists or fleeting suggestions.

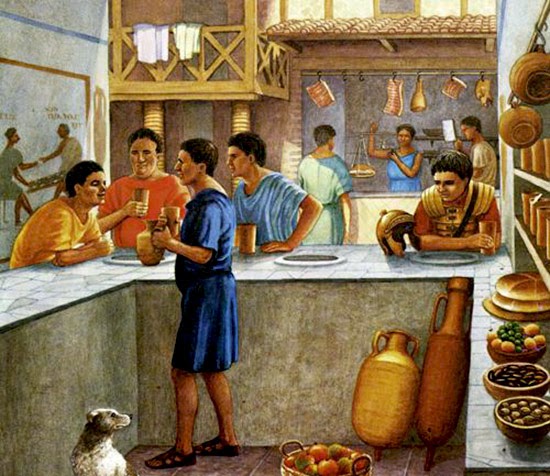

Several Roman authors insert here and there the praise of a fine wine or the contempt for a bad one, with adjectives that can resemble those we use today, without never giving us an exhaustive description. Depending on the case, the taste of the wine is defined austerum (austere), dulce (sweet), tenue (light), pretiosum (used for velvety, soft wines), solidum or consistens (full-bodied, structured ones), ardens, indomitus or generosus (for wines with important alcoholic gradations), fragrans (fragrant). There are also adjectives as suave (semi-sweet, drinkable), vetulus (old), fumosus (with a smoky taste). The sparkling wines are saliens, titillans, spumans, spumescens, made such by the presence of the bullulae, the bubbles (in late Latin). There is no lack of criticism for a wine that is fugens (weak), asperum (acetic), acerbum, agre or acutum (too acid), vapidum (that has lost its characteristics), faeculentum (turbid), sordidum (of very poor quality), etc. Of course, there were also expert tasters at the time, called haustores.

However, we thinks often about Roman wines as strange concoctions, added with incredible things. Are we really sure?

According to Plinio, the great wines are recognized precisely from the fact of being good by themself. It is therefore a sin to spoil them by adding more. Conversely, if the place produces weak wine or if the vines are young, he advises to intervene by different practices to improve the taste and prolong the wine life.

Columella also clearly says that wines from the best grapes and from the best territories do not need any particular cellar intervention. It seems to feel a today’s artisan winemaker:

“We will consider excellent any quality of wine that can age without any addition, without mixing any substances which can altered its natural flavor. In fact, the best things are those that can be appreciated for their intrinsic characteristics”.

Columella, however, gives us a “prank”: he does not explain us, in detail, the winemaking practices for the great wines, those that did not need any addition. Especially, macerations are a great mystery. From the other authors we can expect it, but not from him.

Perhaps he is like a great cook, who does not think of writing all the passages of his recipes because he takes him readers’ knowledge for granted. Or, perhaps, he is more thorough in describing viticulture because he knows it better, while about winemaking he reports (more briefly) the experience of others. Or, simply, he does not attach importance to these steps. We will never know. Like Pliny, he lingers long on the advice for handling and the additions to the less valuable wines.

However, all ancient texts reveal two distinct types of wines, common to all eras: those of high value and those of low level.

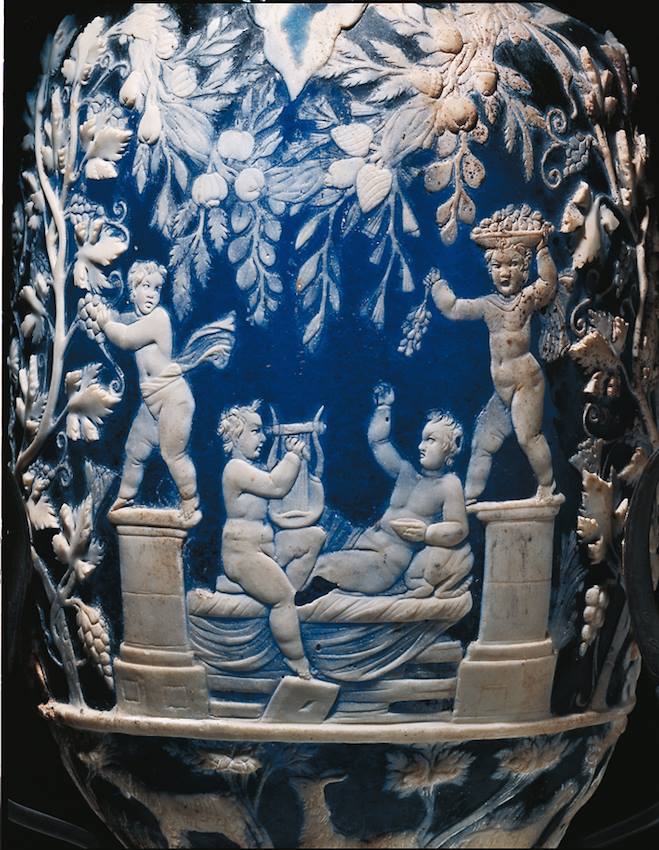

The high quality and high price wines are described as very pleasant and refined, capable of very long aging.

They are produced mainly from the estates of Roman patrician families, located outside Rome or, above all, in the area of North Campania. This is a typical element of the wine production of all times, including ours: the best wines are not only the good ones, but those that are produced by wineries or production areas that manage to impose themselves for reasons of power and wealth, besides geographical ones. It cannot be denied that in the past often the best production techniques were exclusive to those who had a higher education and the possibility of buying the best technologies of the time, thanks to their social position. Today the greater economic capacities essentially allow a much more effective marketing, precluded to the smallest winemakers.

The largest production, on the other hand, involved modest wines of low value and cost. They were not only simpler in taste, as happens today for cheaper wines. They were wines that underwent numerous manipulations and corrections in the cellar. Their not excellent taste was often covered with addition of aromas, spices, honey or cooked must, as in the Roman archaic era.

Starting from these incomplete sources, wine historians have made various hypotheses over time on how the best Roman wines could be. The Italian specialist Antonio Saltini examidem them. In 1839, Giorgio Gallesio assumed that luxury Roman wines were all liqueur wines, as the actual Tuscan “Vin santo”, but there is no direct evidence in this sense.

Starting from these incomplete sources, wine historians have made various hypotheses over time on how the best Roman wines could be. The Italian specialist Antonio Saltini examidem them. In 1839, Giorgio Gallesio assumed that luxury Roman wines were all liqueur wines, as the actual Tuscan “Vin santo”, but there is no direct evidence in this sense.

Hugh Johnson wrote (“The story of wine”, 1989) that Roman fine wines were all white and sweet, because no author describes the maceration phase. They sometimes claim to remove the skins quite quickly after grapes squeezing.

His hypothesis, however, goes against the evidence that Latin texts speak widely of wines of many colors, even more than today. The reds are distinct in: sanguineum (blood color), purpureum (purple), niger or ater (black or dark). Then there are: album (white), fulvum (orange or amber?), pallidum (Galen describes it as a in-between white and orange), rubellum (rosé?). We must remember that, in any case, too long periods of maceration are not needed to extract color.

Some descriptions of the wines already mentioned above do not play in favor of this thesis. For example, Horace, in ode XXVII book I, uses the expression severi falerni, which gives more the idea of an austere rather than sweet Falerno wine.

Moreover, the long aging of a wine with a sugary residue is much less easy than for a dry one, especially without our modern technical competences, unless it is a mutated wine (a technique with which fermentation is blocked with the addition of alcohol, which acts as a preservative thanks to the fact that it prevents the development of any micro-organism; it is typical of the production of sweet aging wines such as Marsala, Porto, Madera or different Muscat from southern France). However, this practice was unknown to the Romans, as far as we know; it was introduced only from the 13th century.

Tim Unwin wrote in his “Wine and the Vine: An Historical Geography of Viticulture and the Wine Trade” (1993) that the best wines of Rome were suitable for very long aging because they were subjected to very long macerations at high temperatures, so as to extract all the color and tannin possible from the skins. These hypotheses are not supported by the sources, as already explained above. Furthermore, this production system would lead to other inconveniences that are not really of high quality. However, the acid component of the wine is much more important for a long aging than tannin. Acidity depends above all on the compositional balance of the grapes.

Antonio Saltini is more in agreement with Dalmasso and Marescalchi (“History of the vine and wine in Italy”, 1931-1933-1937), which argued that it is very difficult for us to imagine wines that have undergone smoking in the apotheca and the decades-long aging times ( sometime also centenarians), which Latin authors often boast of the most prestigious wines, or with the “strange” additions made to less valuable wines (such as sea water or other).

I think, however, that many questions remain unanswered. Does the passage in the heat of the apotheca change the taste of the wine or it serve only to heat the amphorae? Are true these incredibly long aging times or only hyperboles to praise a wine?

Furthermore, some of the Roman winemaking additions are not so strange as we can think. For example, in all texts about Roman wines we can find their use of pitched amphorae or addition of pitch to the wine. Written like this, out of ignorance, I immediately think of pitch as a derivative of tar. It is very difficult for me to think of drinking anything that has this flavor or was been in contact with it. However, I tried to go deeper (thanks to Luigi Manzi “Viticulture and enology among the Romans”, 1883 and the modern archeologists analysis of these compounds) and found that in ancient times the term also has another meaning, today in disuse or little known. In fact, the pitch is nothing but resins of some trees. We will see these aspects in more detail later, as I will explain to you that other strange additions actually are close to some wine adulteration of even more recent eras.

Furthermore, some of the Roman winemaking additions are not so strange as we can think. For example, in all texts about Roman wines we can find their use of pitched amphorae or addition of pitch to the wine. Written like this, out of ignorance, I immediately think of pitch as a derivative of tar. It is very difficult for me to think of drinking anything that has this flavor or was been in contact with it. However, I tried to go deeper (thanks to Luigi Manzi “Viticulture and enology among the Romans”, 1883 and the modern archeologists analysis of these compounds) and found that in ancient times the term also has another meaning, today in disuse or little known. In fact, the pitch is nothing but resins of some trees. We will see these aspects in more detail later, as I will explain to you that other strange additions actually are close to some wine adulteration of even more recent eras.

If the taste of these wines remains for us a great unfathomable mystery, as well as some aspects of their winemaking, we can say however with Manzi (Luigi Manzi “Viticulture and enology among the Romans”, 1883), which they undoubtedly achieved high production levels, with meticulous care of works, both in the vineyard and in the cellar.

Saltini disagrees with Manzi, but I think that a nineteenth-century scholar can better understand Roman viticultural techniques than we can do, with our prejudices. They were more like those of his time that ours. For example, Columella recommends making wine, for great wines, only healthy and well-grown grapes. They already knew very well the importance of temperature during winemaking, moving the amphorae to heat or cold, depending on the winemaking stage or wine typology. They already produced sparkling wines, they already had an awareness of the need for hygiene and cleanliness, etc. Of course, however, they lacked all that knowledge about microbiological aspects, the discovery of which will be a break for the birth of modern wine in the nineteenth century.

Putting all these elements together, what can we think about the best Roman wines?

Putting all these elements together, what can we think about the best Roman wines?

I think we can dare to approach them to the luxury wines of more recent times, which had a fairly similar level of knowledge and technical development in the vineyard and in the cellar. The Roman best wines may therefore not be so different from the best wines produced between the seventeenth and early nineteenth centuries.

We know that history often repeats itself. The great viticulture and winemaking knowledges of the Romans will be almost completely lost in the Middle Ages, although partly preserved in the libraries of the monasteries. Many of these techniques will then be “rediscovered” in the following centuries, especially from the seventeenth century onwards. The very important leap in knowledge and technology towards the modern wine production will start only in the second part of the nineteenth century.

We can imagine the very small category of luxury wines of these eras as the result of a very accurate production in the vineyard and good winemaking techniques, although still very limited. These wines were characterized by good aromas, body, probably excellent acidity, which made them suitable for long aging. The long aging was possible thanks to the containers (amphorae) well protected from gas exchange thanks to the internal coatings with resins, which also covered the cork stopper. This aging capacity will be re-proposed only from the 17th century onwards, with the introduction of glass bottles closed by cork, which use will be diffusely only since the nineteenth century.

Most likely, they had more or less strong oxidative notes and a more or less intense acetic flavor, as was common in all wines not so long ago. For Roman wines, we must add some more unknown aromas to us, such as the resin flavors (more or less intensely) released by the coating of the containers, perhaps some smoky aromas. These tastes are not familiar for us, but perhaps acceptable for an ancient palate accustomed to them.

This little game is over, in the next post I will tell, in broad terms, the viticulture and the Roman enology.

Bibliography

Columella, “De re rustica” , 65 d.C.

Luigi Manzi “La viticoltura e l’enologia presso i Romani”, 1883

Dalmasso e Marescalchi, “Storia della vite e del vino in Italia”, 1931-1933-1937

Emilio Sereni, “Storia del paesaggio agrario italiano”, 1961

Enrico Guagnini, “Il vino nella storia”, 1981

Hugh Johnson, “The story of wine”, 1989

Tim Unwin, “Wine and the Vine: An Historical Geography of Viticulture and the Wine Trade” (1993)

Antonio Saltini, “Storia delle pratiche di cantina, Enologia antica, enologia moderna, un solo vino o bevande incomparabili?”, Rivista di Storia dell’Agricoltura a. XXXVIII, n. 1, giugno 1998