Experimentation and Research

Viticulture and wine production, although thousands of years old, never ceases to be an area to explore and understand. There are no points of arrival in our work. We are always learning because we are dealing with living organisms in close relationship with their environment, subject to the constant changes of vintages, as well as the wider impact of climate change.

For these reasons, we have always conducted research, both internally and in cooperation with universities and research centers, in order to increasingly improve the development of sustainable viticulture and our production. Research in our field is not easy, because the grape harvest only takes place once a year. It must, therefore, be spread out over extended periods to provide answers.

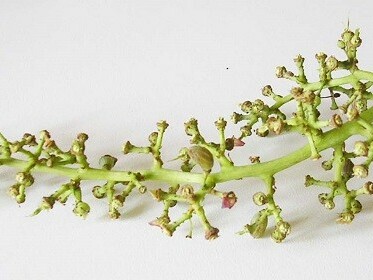

There are numerous experimental varieties in our vineyard, including varieties from arid areas, which are useful to understand how we can adapt to our changing environment and climate. We are also experimenting with new rootstocks that are more resistant to drought conditions, in combination with the main varieties of our area. In addition, we are also studying the response of some resistant varieties to our terroir … Experimentation in the vineyard translates into a complex series of vinification of samples, to follow the transformation of the grapes into wine and understand their potential.

Winemaking: high-quality artisanal production

There is no pre-established recipe in artisanal production: the beauty and the difficulty of this work lie precisely in understanding how the winemaking methods change every year and between the different lots of grapes. Every decision derives from tasting, accompanied by analysis. Tasting remains irreplaceable for grasping the complex balances that are the basis of a great wine.

Each step of the vinification and aging must be done with extreme care and skill but, in our opinion, it should affect the characteristics of the wine as little as possible. Wine personality remains unique if it essentially depends on the grape and the territory. However, this is possible only if an excellent job has been done first in the vineyard.

Only starting from optimal grapes (balanced, healthy, harvested at the best moment of ripening and selected) is it possible to carry out a cellar work that enhances the territorial characteristics, avoiding the use of chemical-physical interventions that alter their nature. Always with this in mind, we have chosen wine vessels and cellar tools among the most neutral ones, which affect the characteristics of the wine as little as possible, such as barrels that are not new.

The grapes are vinified in small separate lots, coming from micro-zones of vineyards with homogeneous characteristics. Each lot is thus followed with extreme care and in the most appropriate way for it. Some lots are mono-varietal. Others are the result of a careful study of field-blend, to obtain the unique synergies that develop from the co-fermentation of several varieties.

At the end, we analyze the wine to ensure the absence of any unwanted residue.

Some key elements:

The grapes, after being harvested and selected, arrive in the winery (once called “tinaia” in Tuscany). To produce red wines, a destemmer-crusher is used, which removes the stalks and crushes the grapes very gently. The berries and the juice are moved to a fermentation tank. To produce white wines, after destemming, the grapes are pressed very softly.

The production of white wine is much more delicate than red, because it alters much more easily. The juice must be cleaned of all the vegetable remains. We do this by natural precipitation of the turbidities, leaving it in a cool place for one night. After that, the juice is transferred to a new tank.

Our job is to facilitate the alcoholic fermentation making sure that it takes place under the best possible conditions. It is important that it goes on slowly and in a regular way. We promote a high biodiversity of fermenting organisms in the first part of the proceedure, that promotes more complexity into the wine. When needed, the wine is briefly exposed to the air to give oxygen to the yeasts. Fermentation lasts an average of a week or so and ends naturally.

We vinify single lots of homogeneous vineyard parcels separately. Some lots include only one variety. Others come from the traditional practice of field-blends, fermenting several varieties together. The result is not the same: a synergistic effect develops in the co-fermentation which gives rise to unique aromas and flavours. Co-fermentation is possible for batches of grapes that have similar ripening times.

Maceration takes place simultaneously with the fermentation in red wine production. The grape skins, immersed in the juice, gradually yield colour, aromas, aromatic precursors and tannins. The duration of the maceration depends on the type of grape, of wine to be obtained (younger, less or more aged). It is not standard in artisanal production: it changes every year and for the different vineyard parcels.

The grape skins form a compact mass, called “the hat”, which floats on top of the fermenting wine. This hinders the desired extraction process and the skins could be subject to microbial contamination or other problems. Thus, it is necessary to gently stir the mass to avoid the formation of the hat. The frequency varies according to the grapes, the vintage and the wine types. We make fulling in the smaller vats, i.e. we stir with a long pole. Pump-overs are practiced in larger vats, with the use of a tube and a pump.

This marks the end of the maceration for red wines. The correct moment to do this is not easy to interpret for a high-quality artisan wine. It is decided with the gustatory evaluation of tannins, which can only be made by an experienced person who knows what they are doing. The practice is done by stopping the mixing of the tank and leaving the hat to form. The wine is slowly removed from the bottom of the tank. The pomaces are then pressed very gently to recover the part of quality wine that they still contain. They are then sent to the distillery for the production of grappa.

Malic acid is a grape component that can remain in the wine. It could be fermented by the lactic bacteria. Once this process was called the “second fermentation”. The acidic taste of the malic acid is very aggressive. Its content is highest in the unripe grape and decreases during the ripening, in a different way according to the climate. The high temperatures of the Mediterranean climate degrade it almost completely. So, it is absent or very low in ripe grapes. On the contrary, it is less degraded in cold climates, and the malolactic fermentation is very important to decrease the wine’s acidity. Moreover, that process adds some typical aromas.

Our white wines remain in the fermentation tank for aging on the lees, with frequent stirring. Aging gives more evolved aromas and the wines become more complex. Aging lasts around 4 months for our young wine L’Airone, around one year for Criseo, giving it a good longevity. The wine is clarified by natural decantation of the lees at low temperature.

Aging in wood is not possible for every wine: it is possible only with the right terroir and grapes, optimal balances, an appropriate vinification … The Bolgheri DOC production code establishes minimum maturation periods. Our red wines remain in the barrels from eight months to two years, depending on the types. We use small barrels (225 and 500 liters), not new. New barrels release strongly aromatic compounds, such as wood aroma and vanilla. We prefer the oak influence not to be too invasive.

Oak is a porous material and, with time, some of the wine tends to evaporate, lowering the level of wine in the vessel. This situation can then create a surface contact with air, subjecting the wine to irreversible alteration, oxidation. The casks are kept in the cooler and more humid area of the winery (called “bottaia” in Tuscany), in order to limit evaporation. However, each barrel must be continuously monitored and topped up if necessary.

The aging of red wines is traditionally done on the lees, with the remaining yeast from the fermentation. This practice has a positive influence on the body, stability and complexity of the wine. This process requires labor-intensive monitoring. The lees tend to precipitate out to the bottom of the barrel. So, the content of every single barrel must be stirred at least once a week. The wine must also be tasted periodically, to avoid reduction phenomena caused by the lees that could affect the wine taste. If we find them in time, we resolve them with a wine aeration.

We do some racking at the end of the aging to clarify the wine (it is not filtered). We stop stirring of the barrels in the last months. The lees settle on the bottom and we gently transfer the wine into another barrel. A wine could be racked 5-6 times or more, depending on its state. There is the possibility that a very small amount of sediment is present in the bottle: it is a sign of an artisanal wine.

Each barrel experiences its own evolution during maturation. Each barrel contains wines born in a vineyard parcel, with one or more varieties. These individual lots must then be combined with care, expertise and sensitivity to construct the definitive blend. The final blend rests some months in a tank, so that its constituent parts can marry naturally together. It is like a birth: it requires time, so that the individual parts can create something that is not simply the sum of them but the expression of a unique synergy.

Sulphites are produced naturally in wine, since a small part comes from the metabolic activity of the yeast. The introduction of sulphites in wine is due to its properties as an antimicrobial, antioxidant, and preservation agent. The amount is determined at bottling.

After bottling, we let the wine rest in the bottle, stored horizontally, for a period of three months to several years, depending on wine type. A shot period in the bottle allows the young wine to “recover” after the stress of bottling. During longer periods of ageing, transformative processes take place, with a softening of the tannins, tempering of acidity, and evolution of aromas, which complete the personality of the wine.

Insights

The new European wine labelling rules

11 December 2023

We’re certifing our wines as sustainable

27 June 2022

Stem or not stem vinification?

28 March 2022

2021, a remarkable vintage: about the harvest

16 October 2021

We present our vineyards 1: Campo Bianco

30 June 2021

In the vineyard: grapes and the environment

The production of terroir-expressive wine requires an optimal vineyard management firstly.

The vineyard is a complex ecosystem, formed by the vines and the soil, its natural surroundings and the living beings that inhabit these spaces. Respectful management makes it possible to achieve a balance that can develop resilience and adaptability and allows external inputs to be increasingly reduced. The necessary interventions come with the experience of the winegrower, with systems with the lowest possible environmental impact, in the light of current knowledge.

Work in the vineyard follows the natural cycle of the vine and is strongly determined by seasonal trends. There is a lot of work to do, all aimed at getting each individual vine to find an optimal balance. It is not an easy because, if done well, it must be tailored to each micro-parcel of vineyard and changes every year. It requires picking up on sometimes imperceptible changes, knowing how to make the right decisions at the right time, sometimes even taking a bit of a risk. Being a vine grower means having the privileged position of living in the vineyard every day and knowing it inside out.

Some key elements:

The creation of a vineyard should never be casual. It is important to make the most appropriate choices according to the nature of the land. The soil and the micro-climate of the plot condition the choice of the varieties to be grown, the rootstocks, the type of wine that can be produced there, the distances between the vines, … Our vineyards are on average very dense (around 8,000 vines per hectare) to maintain optimal production for each individual vine.

The vine training system is set in the first years of growth and will remain throughout the life of the vineyard. It is important for grape quality because it influences the physiology of the vine. It must be chosen according to the variety of the vine and the characteristics of the terroir. Our vines are trained by spurred cordon and guyot (depending on the variety), two Italian traditional systems that enable a high level of grape quality and excellent vineyard management. In the historical vineyards, we use the vine married to the tree method, the ancient Egyptian tunnel pergola and the ancient Greek bush-trained system.

Soil management is fundamental to the balance of the vineyard. We strive to ensure that the soil is vital and that the vegetation does not create problems for the vines. We chose spontaneous grassing of the vineyard because it promotes a natural water balance. In cooler seasons, it avoids excess water and nutrients, counteracts erosion and stagnation. While in summer the grass dries up spontaneously in our climate. The spontaneous meadow has a high biodiversity: it is an attractive habitat for useful micro-fauna. It allows us to reduce inputs into the vineyard, reducing fuel consumption and avoiding soil compaction problems. When necessary, we till the soil and green manure grass is an excellent fertiliser for the vines.

The vine is not a demanding plant, but it must have enough nourishment (mineral salts) to produce excellent grapes. The needs vary according to the climate, the soil, the variety, the rootstock, the seasonal trend, … The enrichment of our soil with organic matter occurs mainly from plant remains. They derive from the mulching of the remains of grass cuttings, from the pruning, from the stalks, … These are shredded on site and become compost which enriches the soil with nitrogen, calcium and potassium. The high biodiversity index favors the mineralization of organic matter and the correct distribution of these nutrients. Mineral fertilization is done only when and where needed.

Thanks to our well-ventilated Mediterranean climate, we generally have few vine disease problems. In any case, we follow the principles of integrated viticulture, based primarily on biological control, agronomic prevention (adequate pruning and canopy management), the minimal and targeted use of biodegradable or low environmental impact defense products. This setting allows us to verify the absence of any residue both in the wines and in the vineyard.

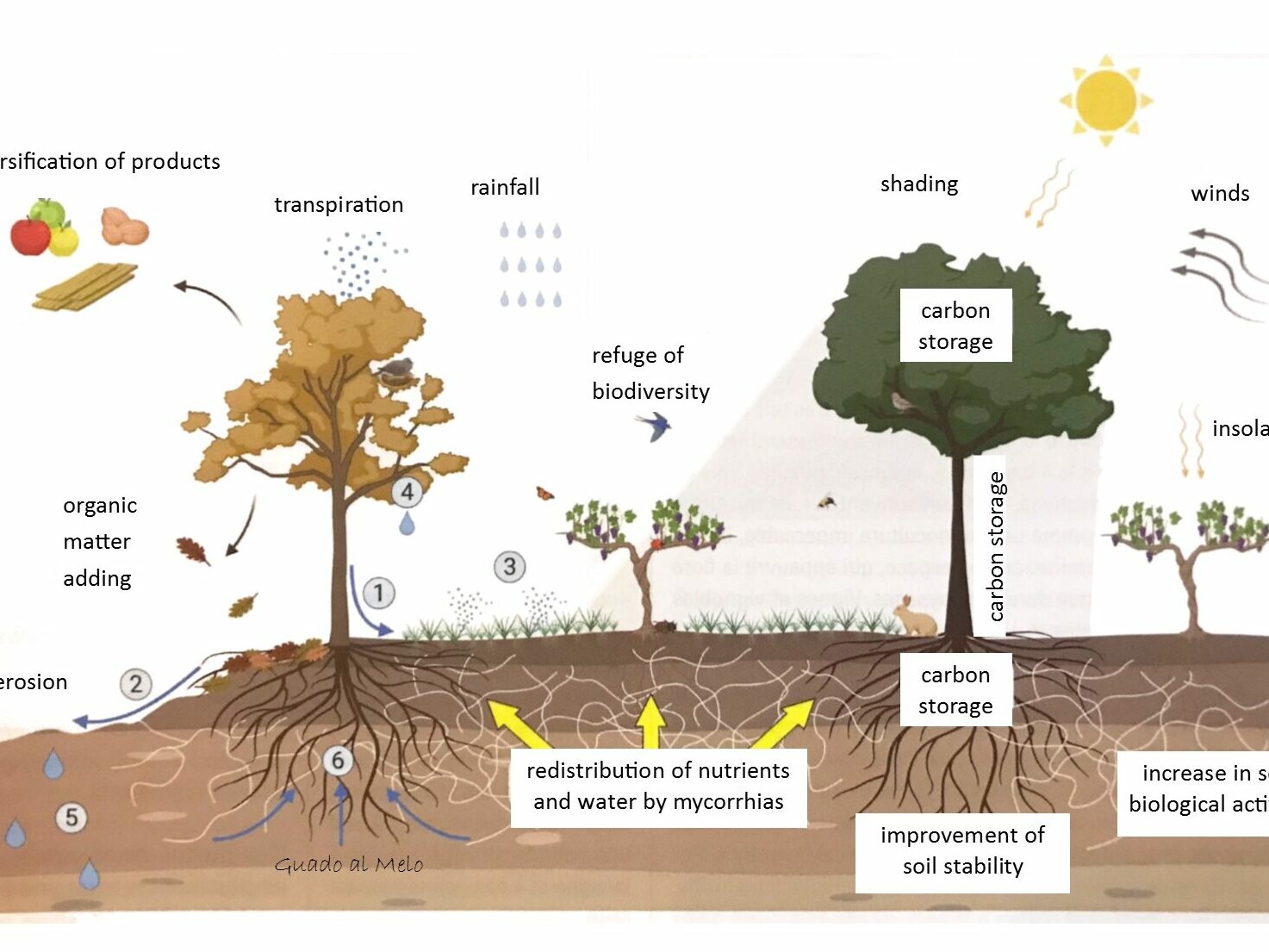

Biodiversity is encouraged by our low environmental impact practices, spontaneous grassing and contiguity with hedges and woods. The high biodiversity index is an important element of biological control. It favors the balance of the vineyard because it has a positive effect on the recycling of organic matter, the nutritional availability of the vine, the control of diseases and parasites, the quality of the soil and the water cycle.

Winter pruning is the first among the many jobs necessary to direct the vine to a harmonious balance. In winter, when the vine is at rest, the branches of the past year are cut. We leave a certain number of buds for the following year, carefully evaluated. Too many would cause an excess of grapes to be produced. Too few would induce too vigorous growth of the green parts, reducing energy from the ripening of the bunches. Pruning can only be done by hand and requires great expertise as each plant must be evaluated individually.

This job is performed on the shoots from spring onwards to give the right balance to the canopy of the vine, i.e. the mass of leaves. The canopy is very important because it represents the vine’s ability to absorb sunlight and use it for its own growth, production and ripening of the grapes. At the same time, however, it consumes part of the plant’s resources, so it shouldn’t be excessive. Its optimal balance is different depending on the environmental conditions. The orientation of the shoots is also important, which in turn is linked to the vine training system.

As the vine grows, it tends to continuously lengthen the shoots (this is called “apical dominance”). Over time, however, the leaves at the base age and are no longer as efficient in their photosynthesis. The topping, i.e. the cutting of the tips of the shoots, serves to contain their growth but also to stimulate the lateral buds. These form new leaves, young and very efficient, capable of supplying new energy to the plant in the summer, when the grapes are ripening. When and how to do it depends on the vineyard, the grape varieties and the trend of the weather.

The quality of the grapes also depends on the number of bunches that each plant brings to maturity. It is a choice to be carefully evaluated. It changes with the variety, the type of wine, the environment, the vintage, the plot, … For the final quality of the grapes, it is important that the yield is low. However, even too low a yield can become counterproductive in very hot climates and years, because it involves too fast ripening, unbalanced grape production, with excessive alcohol, … The quantity of grapes produced is managed with different interventions, such as pruning and thinning of the bunches.

In general, it is preferable that the bunch is shaded by the leaves in a sunny environment like ours. Excessive exposure to intense sun causes burns that alter the quality of the grapes. On the other hand, in particularly humid years, it may be useful to improve exposure by removing some leaves around the bunch, to circulate the air and avoid the development of rot and mold.

The decision when to harvest is crucial. Making a mistake means risking the efforts of the entire year. The ideal harvest time is different depending on the variety, the type of wine (young, for aging, …), the micro-zone of the vineyard, … When we are close, we follow the trend day by day. The decision comes from a complex set of evaluations: the tasting of the grapes and the analyzes (sugar content, acidity, polyphenols). At this point, the grapes of each homogeneous micro-zone are harvested, selected and processed as quickly as possible, to avoid any deterioration of the fruit.

Insights

What is Sustainable Wine?

We come from a family of winegrowers and our sustainable approach was born with the estate itself. We have always adhered to the integrated viticulture system of the Tuscan Region. In 2009 we joined the first Italian sustainability certification, called Magis. In 2022 we achieved the single national sustainability standard (Sistema di Qualità Nazionale di Produzione Integrata).

But what does it all mean?

Making sustainable wine means, in a nutshell, working effectively now while preserving resources for future generations.

The idea that human activities could negatively affect the environment is ancient. However, it was only in the 1960s that the irresponsible industrialisation of the countryside led to the emergence of an more widespread environmental consciousness.

It was then that the idea was born that it was possible to use research to create a new agriculture, capable of responding to human needs, but more respectful of the environment and health. Thus, integrated viticulture (agriculture) was born. Over time, research has allowed practices to continuously evolve, reducing the negative impact on the environment and on our health.

A major leap forward was made in the 1990s, when the broader concept of sustainability was born, combining environmentally friendly farming practices with the concept of economical production and respect for the social sphere.

Here are some key terms and our sustainable choices:

This is the area of sustainability that includes working practices in vineyard management. It is a system that has evolved over time, regulated in Italy by the regional authorities, which admits only the best practices, taken from tradition and the best innovations that have proven to be effective and have the lowest environmental impact. Priority must be given to biological control and prevention practices. Any intervention must be done in a targeted and differentiated manner: only where it is needed, when it is needed and in a specific way according to the needs of each micro-zone, including accurate monitoring systems. Some basic practices of integrated viticulture are now compulsory for all Italian wineries, but full adherence to these principles is on a voluntary basis.

The leap forward that led to the birth of integrated viticulture depended above all on the great development since the 1950s of knowledge about plant biology and pathogenic organisms. In particular, ecology, the science that studies the mechanisms of interaction between animal and plant populations living in a environment, was born. Studies have increasingly emphasised the importance of vineyard management as a complex ecosystem, an integrated ecological system where the various players intervene substantially in the nutrient cycle, in impacting soil quality, and in containing pests and diseases.

Biodiversity in the vineyard has not only environmental but also agronomic value. The wealth of flora in and around the vineyard promotes the presence of micro-fauna that are useful in containing certain vine pests. Soil micro-organisms (bacteria, fungi, mycorrhizae, etc.) degrade organic matter and make mineral elements available to plant roots. Earthworms modify the communities of bacteria and protozoa in the soil by digestion and operate a positive selection on fungi, improve the availability of water and oxygen in the soil, promote the growth of flora and the development of micro-organisms that are agonists of vine root aggressors.

The quality of the soil is crucial for the vitality and health of the vines. Intensive vineyard management has proven to be counterproductive because it increasingly worsens the characteristics of the vineyard and thus requires ever greater human input. Conversely, well-managed cover and a high biodiversity index improve the balance of the vineyard over time. Low-impact interventions protect the soil by preventing its compaction and the accumulation of pollutants.

Sustainable management means less impact of the vineyard on the landscape. Our vineyards are small and integrated with hedges, trees, olive groves and woods. Ecological management makes them ‘green corridors’ that can be travelled by small animals moving in the area and into the surrounding woods. A low, wide-meshed fence protects our vineyards from wild boars, but allows small, not too harmful fauna to pass through. The underground winery blends into the landscape.

The vineyard is not demanding of water, provided it is cultivated in the right environment, with soils that allow for root expansion like ours. We have chosen native species that do not require irrigation for the spaces around and on the ‘green roof’ of the cellar, such as olive trees and other plants of the Mediterranean scrub. Wine production generally involves the high consumption of water especially for cleaning and hygiene of the wine cellar. We have a rainwater collection and recycling system to contain this, saving at least 40% of potable water. Cellar waste water is purified with a biodigester.

The underground cellar allows energy savings of at least 70 per cent compared to an equivalent above-ground cellar. It maintains temperatures and humidity suitable for wine in a natural way. Well-designed skylights and patios allow sunlight to illuminate the most used work areas. Energy-efficient lighting fixtures and machinery have been chosen in the winery. Fuel consumption is limited thanks to the integrated viticulture concept aimed at reducing inputs to the vineyard.

The principles of bio-architecture, which inspired our winery, bring together several cornerstones of sustainability. the completely underground structure fits completely respectfully into the landscape. In addition, the underground construction makes it possible not to use energy to condition most of the interior spaces. In fact, there is adequate temperature and humidity all year round. Natural lighting of the most important work areas is provided by carefully designed skylights. A rainwater collection and recycling system preserves water resources. Finally, waste water is purified with a biodigester system

An activity is also sustainable if it is able to be self-sufficient, thus guaranteeing an income for the people who work in it and for the allied companies. Sustainable agriculture does not neglect the social aspects of an activity: its relationship with the land, respect for people and the landscape, … It includes the preservation of the cultural aspects of its product, which must be handed down and disseminated. It attaches great importance to respecting the rights and health of workers: safety at work, valuing and training them.

Insights

Regenerative agriculture (or viticulture)

8 November 2024

Webinar domani con Michele Scienza

14 February 2021

Agroecology in the vineyard, our present and future

28 December 2020

Our new brochure

22 February 2018