Let us drink comrades, let us eat, let us enjoy!

I assure you that of all the things in the world, nothing meets human needs better than this. Everything else indeed escapes us, but let each one know that this is ours, that it truly belongs to us.(“La Catinia”, Sicco Rizzi, 1419)

With this enjoyable invitation, we open this (necessarily incomplete) look at wine in the life and art of the Renaissance and early Modern Age.

Certainly, it was still consumed daily, as it always was in the past. Light wine and wine diluted with water were part of the daily diet for everyone, a safer drink than the contaminated water of the time. The more concentrated wines were dedicated to pleasure, ranging from the barely drinkable ones of the lower classes to the refined ones of nobles and lords.

At this time, however, a sort of ceremonial began to be built around the wine: people began to study it, to look for the best pairing with food, how to serve it, … All this, which for us is normal, was born in the splendid Italian Renaissance courts. It was to be imitated by other social classes, as well as exported throughout Europe.

Wine and court life

The fine wines, which had always been the prerogative of the upper classes, made an important leap forward in the sumptuous banquets of the Italian lords of the time: the Gonzagas in Mantua, the Sforzas in Milan, the Medicis in Florence, the Este family in Ferrara, the papal court and the Duchy of Urbino, … We have numerous literary and artistic testimonies of their sumptuous banquets. The magnificence of those of the Medici was legendary.

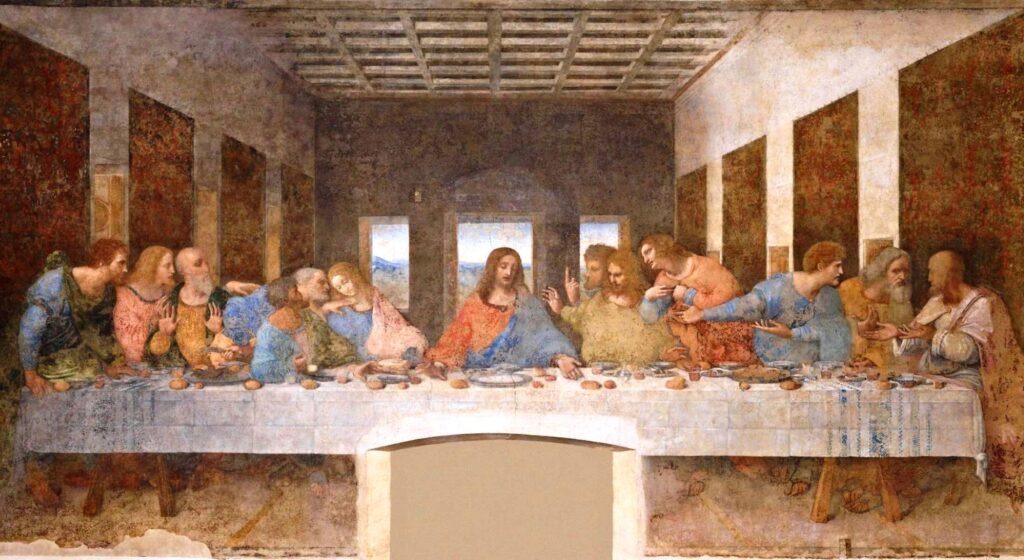

The banquet was an important moment in court life and diplomacy. Every element was part of a carefully studied scenographic representation, intended to show the illustrious guests the power and magnificence of the Lord, expressed with refinement and taste. Cultured conversations took place here, one had to be able to show off one’s manners with grace and ease. The famous treatise “Il Galateo“, written by Giovanni della Casa (1552), was a resounding success throughout Europe. On the subject of wine, the author recommends moderate consumption, because drunkenness does not suit the courtier: he must maintain his self-control. On the other hand, he deprecates the fashion of the toast, which was then arriving from abroad, which the author considers inelegant.

Banquets made the selection and service of fine wine a kind of ceremony, with servants and dignitaries dedicated exclusively to it. In the 16th century, for example, the court of the Savoys introduced the “sommelier de corps”, “bottigliere” in other courts, who was responsible for the selection of wines to be purchased, their supply, the choice for the different occasions and the matching with food. The cupbearer, on the other hand, was responsible for serving the wine, diluting it with water and ensuring that no one added poison to the cup. There are treatises describing his skills, appearance, dress, gestures, the side from which the service was to be made, etc. A figure was born that has evolved over time, right up to the modern sommelier.

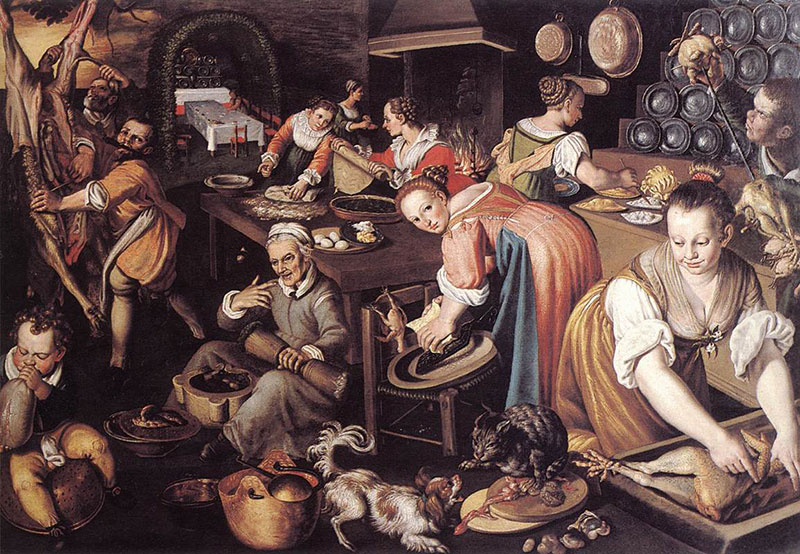

The sumptuous banquets exalted not only the wine but also the food, the pairing between them, and the choice of the most suitable glasses for each wine type. In this era, the cornerstones of the great classical Italian cuisine were laid. On these subjects, we recall the work of Domenico Romoli, the “Singolar dottrina” (1560) and many others.

The life of people who worked behind the banquets was certainly not easy, including that of the courtiers who formed the retinue of the Lords. Enea Silvio Piccolomini, who would later become Pope Pius II, but who was then a simple courtier, recounts in a famous letter (“De curialium miseriis”, 1571) the precarious and difficult life of those who carried out this role, including the boredom of the long ceremonial and rigid etiquette of the time. In particular, he describes the suffering of having to attend the long banquets of the lords for hours on end, suffering from hunger, smelling the fragrances of the superfine foods and great wines that they consumed in refined crockery and glasses. He laments the pitiless comparison with the meals of the courtiers, which they could only consume at the end of these very long days, in filthy rooms, with food of poor quality, accompanied by watered-down and bad wines, served in old wooden goblets, too hot or too cold …

The great food and wine books

The focus on wine and food led to an increasing number of food and wine texts. The first evidence of this genre in Europe dates back to 1230-1250, with the Neapolitan “Liber de Coquina“. Between the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries, many Theatra or Tacuina were written, i.e. treatises that stemmed from monk’s herbals and hygienic-sanitary norms, but which then also dealt with food and wine, the latter also proposed for therapeutic and invigorating consumption.

In the Renaissance, the mediaeval taste for highly spiced and sweet-and-sour dishes continued. The courses alternated roasts and game with waffles and marzipan, meat and vegetable pies alternating with soups, cakes and cream … Tastes, however, began to change. The book that marked the transition to a gastronomy closer to our own was the “Libro de arte coquinaria”, (1456) by Master Martino de Rossi from Como, cook to the lord of Aquileia, Lodovico Trevisani. It was a huge success throughout Europe and was among the most copied. He began to separate the flavours, as well as proposing the importance of using genuine ingredients. He revamped the classic recipes of the time and began to use terms that have come down to us. A curious aspect is that he indicated the cooking time of food with the time needed to recite a certain number of prayers. Another famous author of the time is Bartolomeo Sacchi, known as Platina, with his text on enogastronomy “De honesta voluptade et valetudine” (1474). Above all, he is very modern in writing that good nutrition is also useful for maintaining good health, with exercise and good sleep. Wine, as well as in the recipes, appears in a dedicated chapter, in which the author echoes the writings of Roman authors.

The text by Sante Lancerio, wine steward to Pope Paul III Farnese, was dedicated solely to wine. It includes true reviews of the wines of the time. In his work, he recounts and judges 53 wines, describing the sensory characteristics of the products tasted, their geographical origin, the quantities produced, the best ways to consume them, their pairing with food, … He describes what was to become the classic progression of wine service, with light whites at the start of the meal, the more robust reds for roasts, and the sweet and intense ones for dessert. The meal would end with a kind of bitter, a wine flavoured with herbs and spices, called Ippocrasso. Today these seem obvious to us, but back then they were novelties.

Another author who left us a rich description of wines of the time is Andrea Bacci, physician to Pope Sixtus V and naturalist, who wrote “De naturali vinorum historia” in 1596. This is a much richer treatise than the previous one, with descriptions of wines in antiquity, production methods and descriptions of the wines of his time. His wine history in Italy is very critical: apart from a few quality wines, he tells us that the vast majority were mediocre (as usual at the time). The majority of wines struggled to make it to the end of the summer. They often struggled to sustain transport to Rome.

However, the most relevant contribution of Bacci’s work, even if it is not remembered today, is that he was the first author of the modern era to fully express the concept of territorial wine, i.e. that it finds its identity in its environment of origin, not only in the geographical sense but also in the anthropic sense, in relation to the culture, history and tradition of the territory. This concept, which has always been the cornerstone of wine production in Italy (and throughout Europe), originated with the Romans, will only be deepened and made explicit in the second half of the 20th century, when it will be placed at the basis of modern Denominations, identified with the term terroir (or genius loci).

Wine in literature, from the Stoicism of the Humanists to the great Macaronians.

The Middle Ages are mainly remembered for their goliardic carmina, while the Renaissance Humanists did not devote much space to wine. Humanism aimed at very elevated arguments, with the pursuit of moral and civic values, extolling Christian virtues and independence on earthly pleasures. They rediscovered the classical culture and their favourite Roman references were the learned Cicero or the great Stoic philosophers such as Seneca. One example is Francesco Petrarca who, in a famous letter addressed to his doctor and friend Giovanni from Padova, condemns very firmly the consumption of wine and its excesses (“Res Seniles“, XII, 1), praising instead the superiority of drinking water. I mention this letter because, as you will see below, it will be mocked by more goliardic and less refined authors.

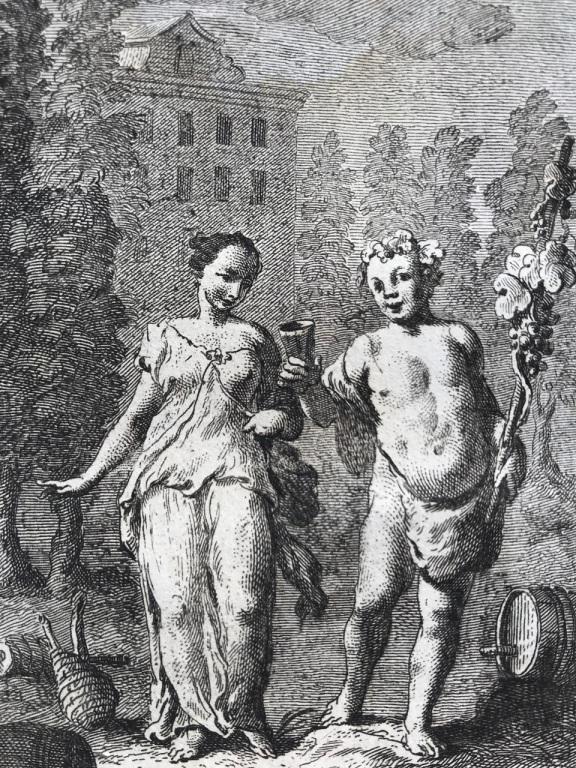

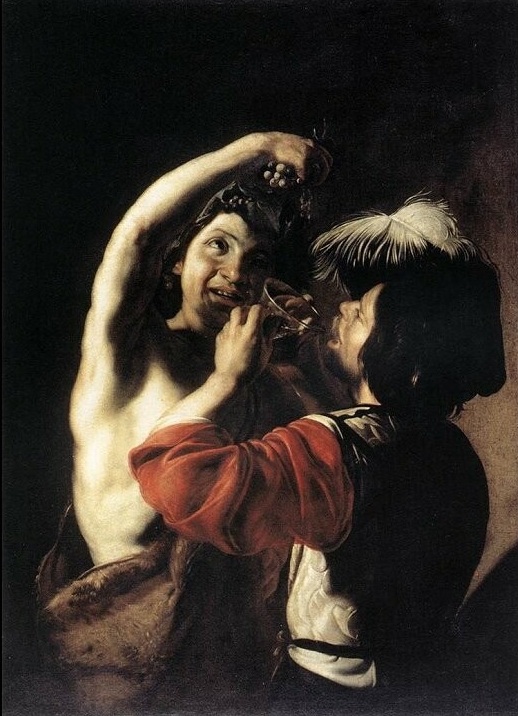

As mentioned, the Renaissance was the time when classical culture was rediscovered and exalted. Bacchus inspired many artists, such as Michelangelo Buonarroti with his famous marble statue of which you can see a detail below (1496-1497). These were intellectual works. Wine and its pleasure often remains only in the background or in the cup that the god lifts, a necessary attribute to represent him.

Lorenzo de’ Medici, the Magnificent, wrote the famous carnival song “Bacchus and Ariadne” (1490). It tells about the theme of the classical “carpe diem”, with the celebration of evanescent beauty and youth. The inebriation is only the comic one of Silenus:

The time of youth indeed is sweet,

But all too soon it slips away.

If you’d be happy – don’t delay!

Tomorrow’s ills we’ve yet to meet.Welcome Bacchus, Ariadne!

An ardent couple, loving, fair.

They spend as one their days with glee,

For time flies fast and does not spare.

Thus these nymphs – and others – fare.

Happy they the livelong day!

If you’d be happy – don’t delay!

Tomorrow’s ills we’ve yet to meet.… (trasl. By Alan D. Corré)

Yet, some illustrious humanists also wrote humorous little stories in good Latin, such as the Tuscan Francesco Poggio Bracciolini. Although he was apostolic secretary, he enjoyed writing the “Facezie” (1438-1452), witty and foul-mouthed mottos in line with his fellow countryman Boccaccio. In the “De potatore” (“Of a drinker”), for example, he tells of a famous wine drinker who, seized by fever and thirst, asks the doctors to cure his illness but not his thirst, which he would take care of himself.

Battista Spagnoli, known as Mantovano, (1447-1516), in the Egloga IX of his major work (“Bucolica seu adolescentia in decem aeglogas divisa”) written in Latin around 1480, describes wine as a way to cure the ills of the soul, which strengthens the body as well as friendships. It takes up a theme of the medieval carmina, where every drink is listed, with the seventh glass triumphing over the drinker. It is little known today, but had great fame at the time. It was proclaimed the Christian Virgil by Erasmus of Rotterdam.

There were also even “lower” and more enjoyable works, such as the quotation I put at the beginning, from the comedy “La Catinia” (1419) by Sicco Rizzi, known as Polenton. It definitely changes tones, but it has in common with Lorenzo the Magnificent the melancholic theme of human frailty, with the imperative to enjoy the present. The work tells of a container salesman who ends up in a tavern full of merry drinkers, where a dispute opens over what is meaningful in life. The theme of wine and the merry life dominates. Water is the enemy of man, it hurts the stomach and makes one stupid, while wine gives eloquence and makes one combative and bold. Here, Latin is deliberately mixed with the vernacular, in a witty language used in satirical and parodic works since the Middle Ages, which later became known as “maccheronico“.

“Bibamus, comedamus, gaudeamus …”

“Let us drink comrades, let us eat, let us enjoy!

I assure you that of all the things in the world, nothing meets human needs better than this. Everything else indeed escapes us, but let each one know that this is ours, that it truly belongs to us.”.

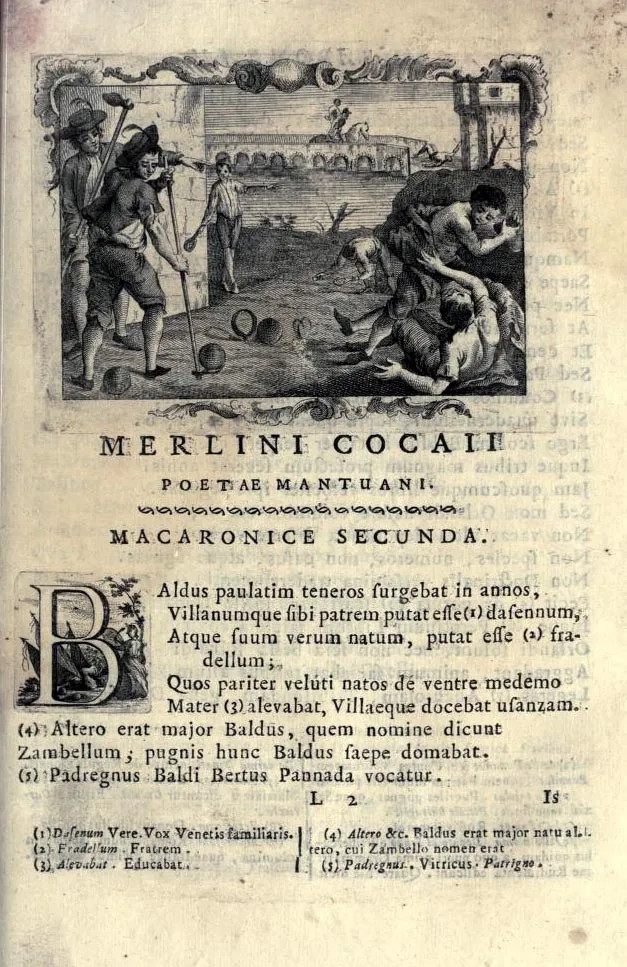

The masterpiece of so-called “carnivalesque” literature and macaronic language is the “Baldus” (1552) by the Paduan Merlin Cocai, pseudonym of Teofilo Folengo, who was to influence European literature a great deal, like the more famous author François Rebelais (“Gargantua“).

He represents a parody of epic-chivalric poem. He always seems to start every speech with moral and constructive teachings, which are then distorted and wittily mocked. For instance, he seems to extol the sobriety of Golden Age men and desert monks, and then describes orgies of food and wine. He describes the banquet of the King of France, prepared by the cook Gambone (Big Leg), with an endless list of game, sauces, sausages, lasagne, oysters, cakes, pastries and rivers of wine, which serve to “quench the flame with flame“. Here he uses the same words as Petrarca in his famous letter in which he praises water. He allows himself to mock him, turning inside out his words to extol the pleasure of wine.

In the proem (the introduction) he does not ask for help from the classical Muses, for inspiration, as was the custom, but from the ‘fat goddesses’, Muses invented by him, who must help him by stuffing him with food and wine. This is where macaroni comes in, from which the term ‘macaronic’ language originated.

Phantasia mihi plus quam phantastica venit

historiam Baldi grassis cantare Camoenis.

Altisonam cuius phamam, nomenque gaiardum

terra tremat, baratrumque metu sibi cagat adossum…….

A more than bizarre inspiration came to me to sing the story of Baldus, with the help of the fat Goddesses. His fame and his mighty name make the earth tremble, and on hearing it, hell pisses itself with fear.

…

But first I need to invoke your help, O Muses who pour forth the art of macaroni. Could my little boat possibly overcome the rocks of the sea, if it is not recommended by your help?

Dictate to me the verses, not Melpomene, not that idiot Thalia, not Phoebus strumming his little guitar; for when I think of the guts of my belly, the chatter of Parnassus is not suited to my bagpipe. Only the fatty Muses, the learned sisters (Gosa, Comina, Striace, Mafelina, Togna, Pedrala) come and feed the poet with macaroni, and give him five or eight bowls of porridge. …

…

There would be an infinite number of quotations but we cannot put them all. The great 17th century Italian wine poem is undoubtedly Francesco Redi’s “Bacchus in Tuscany” (1685). Here the language is Tuscan, which is what will become Italian. This playful poem, beyond its literary value, is interesting because it lists the wines produced in Tuscany at the time, as well as mentioning other Italian wines, such as some from Campania (Falerno, Tolfa, Verdea, Lacrima di Vesuvio, etc.). In the poem he describes 57 types of wines, going so far as to define Montepulciano as the king of them all (Redi was from Arezzo, the territory of Montepulciano production).

I recall that in Tuscany this strong territorial connotation for wines had already been present since the Middle Ages. In fact, this sensitivity would lead, at the beginning of the 18th century, to the birth in Tuscany of the world’s first territorial indications: Chianti, Pomino, Carmignano and Val d’Arno.

It is amusing to read how he deprecates the new drinks that arrived from northern Europe or the Orient, such as beer, cider, chocolate, tea and coffee:

There’s a squalid thing, call’d beer:-

The man whose lips that thing comes near

Swiftly dies; or falling foolish,

Grows, at forty, old and owlish.

She that in the ground would hide her,

Let her take to English cyder:

He who’d have his death come quicker,

Any other northern liquor.

…

Cups of Chocolate,

Aye, or tea,

Are not medicines

Made for me.

I would sooner take to poison,

Than a single cup set eyes on

Of that bitter and guilty stuff ye

Talk of by the name of Coffee.

He uses quite different words for wine, reminding us that it consoles us in life and makes us forget our troubles. He also quotes a famous verse by Dante Alighieri, in which wine is described as the child of the sun:

Dearest, if one’s vital tide

Ran not with the grape’s beside

What would life be

Much too short, and far too stupid.

You see the beam here from the sky

That tips the goblet in mine eye ;

Vines are nets that catch such food,

And turn them into sparkling blood.

…

The vineyard that gives us such pleasures is blessed. The author pleads for it not to be affected by the weather, for nature to gently nurture it, so that its owner in old age can enjoy the wine produced in abundance:

Manna from heaven upon thy tresses rain,

Thou gentle vineyard, whence this nectar floats

May every vine, in every season, gain

New boughs, new leaves, new blossoms, and new fruits:

May streams of milk, a new and dulcet strain,

Placidly bathe thy pebbles and thy roots;

Nor lingering frost, nor showers that pour amain,

Shed thy green hairs nor fright thy tender shoots:

And may thy master, when for age he’s crooked,

Be able to drink of thee by the bucket!

Bibliography:

Piero Stara, Il vino

SIMONA GAVINELLI Gli umanisti e il vino

Luca Tosin, dalla vite al vino attraverso l’iconografia dei libri a stampa del cinque-seicento