“They live in a region that produces everything and, by engaging in work, have fruits with which they can not only eat enough, but also enjoy a life of pleasure and luxury.” Diodorus Siculus (I c. B. C.).

About Etruscan wines:

We have no direct Etruscan written references to their wine; our knowledge comes only through Roman sources. For example, Martial and Horace praised the Massico (from the Etrurian Campania) but they scorned the rosé from Veio. One should not take these negative judgments too seriously, however, since they appear at the historical juncture when the Etruscans were in serious decline, already under the heel of the Roman Empire. Later, Columella wrote, in his 1st-century De re rustica, that numerous types of vines were common in Etruria, such as Pompeiano or Murgentino. Pliny the Elder described different varieties from Arezzo, such as Talpona nera (made into white wine), Etesiaca, Conseminea (excellent for everyday consumption), Sopina or Tudemis or Florentia, Perusinia (a red grape), Parana (in the Pisa area), and Apiana (a muscat grape that made a good sweet wine). The wines from Gravisca (the ancient port of Tarquinia) and from Statonia are described as excellent.

We better know how they consumed them. Rituals connected with wine seem to have already been present in Etruria at the end of the Bronze Age. However, contact with the Greek culture marked a profound evolution. The wine was more deeply linked to the religious dimension, used in a collective way in the celebrations of the Gods and in funeral ceremonies. The greater production made it even more available and became the protagonist of social rites, banquets and symposia (moments after dinner, where wine was drunk, attending music and dance shows, conversations and games). The commonalty probably also consumed a light wine, derived from the marc passed with water, frequent practice also in Roman times and until the nineteenth century.

The banquet had both religious and social meanings, being celebrated during funereal rites, as well as being staged as a symbol of wealth and belonging to an elite class.

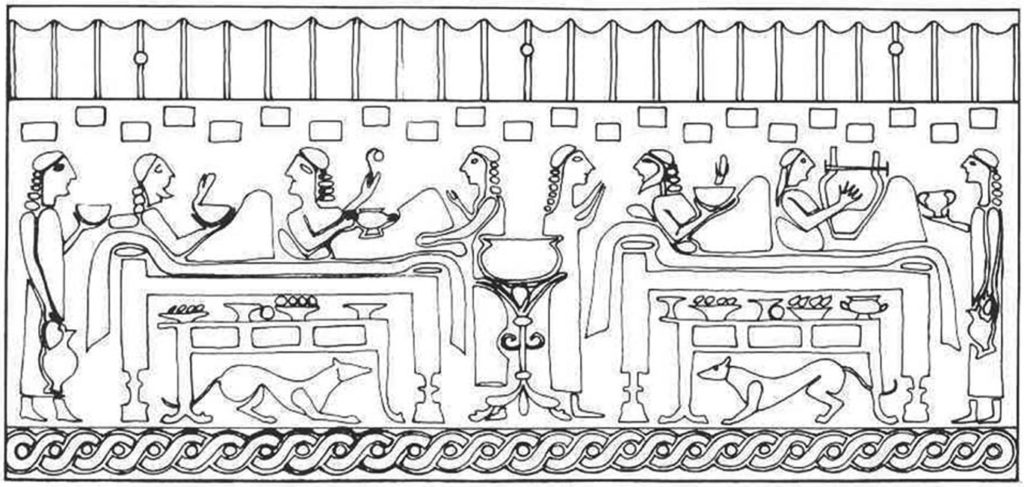

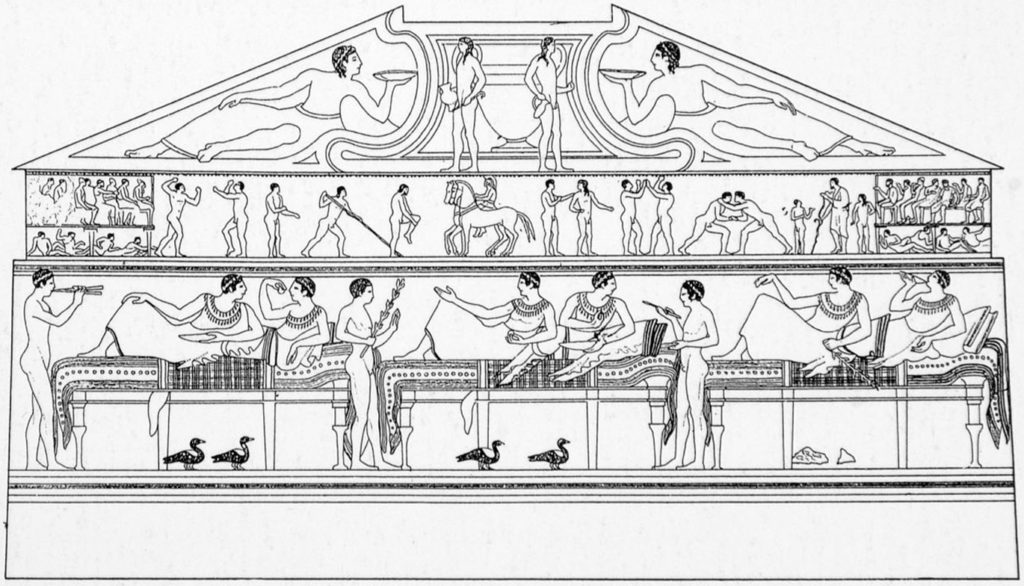

In the first Greek models for marking aristocratic status, the reception of food and drink takes place while seated composedly at a table. This model appears in Etruria at least since the beginning of the seventh century. B.C. Beginning in the 6th century, we begin to see, still drawn from Greek cultural models, the figure of the banqueter, or diner, always half reclining on the kline, or dining couch, elbow resting on one or more cushions. In front of each diner were set some rather low tables, for food and wine cups.

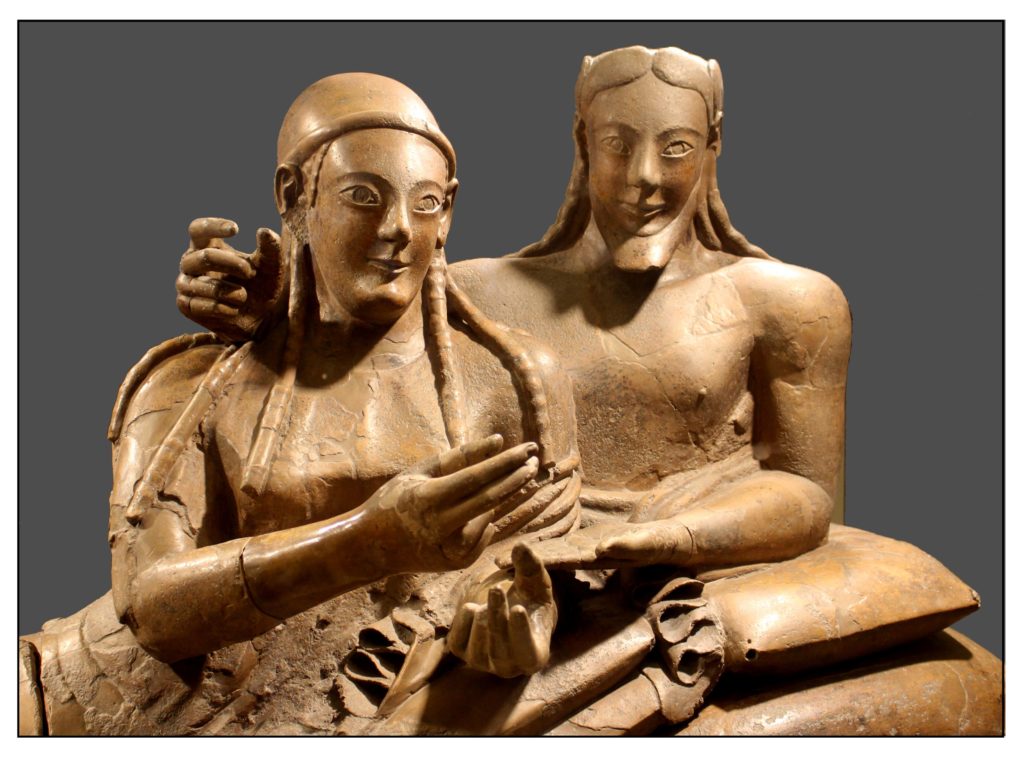

After 500 BC, women are represented at the banquets, sometimes reclining next to the men, sometimes seated nearby. This custom was exclusively Etruscan, since in the Greek world the symposium was solely a male affair, or at most open to the hetaerae, or courtesans. The Greeks, in fact, and the first Romans, regarded the female presence at Etruscan banquets as a sign of moral corruption. As a matter of fact, in the Etruscan world, women enjoyed a social and civic role far different from their subordinate status in Greco-Roman society. Female participation in Etruscan banquets had nothing whatever to do with the erotic or immoral. Rather, married couples took part in these meals, and were represented on sarcophagi and in frescoes as a symbol of family harmony.

The diners ate with their hands, often cleaning themselves with bowls of scented water and napkins. In the room there was pets (dogs, cats, chickens, ducks …), who ate the remains of food that fell (or were thrown) on the ground. The banquet was always accompanied by music, especially from the flutes. There were also dance and juggling performances. There were also games: dice or the “tabula lusoria” (a kind of chess). The kottabos, arrived from the Greek Sicily, consisted in centering a target with the last drops of wine left in the cup.

Moralising criticisms were made by Greek and Latin authors about the luxury that marked Etruscan banquets, which featured precious vessels and embroidered textiles, a great number of servants. Someone tells that they banquet twice in a day! (The Greek and Roman lunch was very light and fast). The Romans went so far as to refer to the Etruscans as “slaves of their bellies” (gastriduloi), and the image of the obese Etruscan coined by Catullus became quite popular. This image, however, was by no means always negative, since in the ancient culture the “fat” person was he who could afford to be so, that is, it was a symbol of wealth and power.

How did they drink wine?

The wine drunk in antiquity was very different from what we enjoy today. It was concentrated, strongly aromatic, and high in alcohol. It was not drunk pure, but mixed with water, because it was considered barbarians to lose control in society. The wine was also sweetened and flavored. These practices were common in the ancient and medieval past, to cover defects due to limited production and conservation techniques.

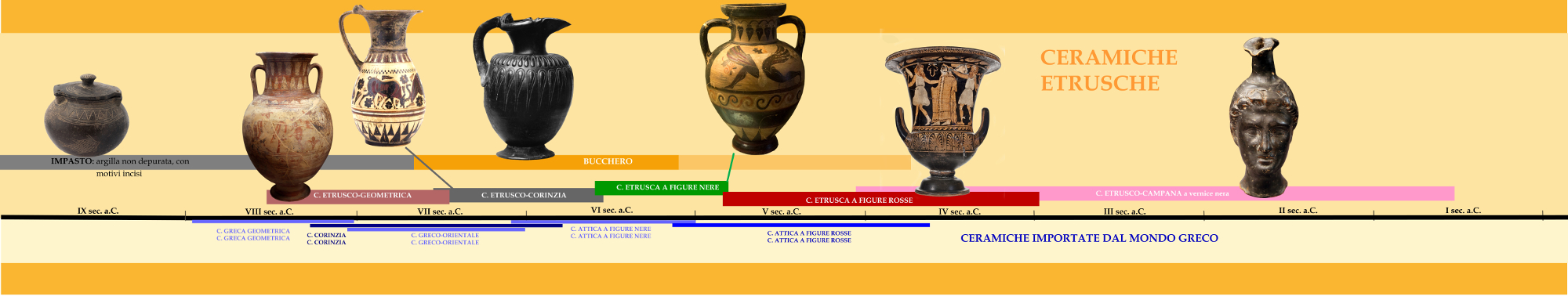

The various utensils used for wine and table were in ceramic or bronze. For them, archaeologists use Greek names because the Etruscan name is often unknown or uncertain.

In the centre of the room, there was a service table with the wine container (krateres), recognizable by the wide mouth. Near, there was a large amphora (hydria) for water, that was served at table with small buckets (situla). The wine was mixed with water in the krater. They used cold or hot water, according to the seasons. Then, they mixed also honey, herbs, flowers, spices, resins, etc.

The grater also belonged to the symposium supply, which was used to grate spices, roots or probably (as happened in the Greek world) cheese. From the crater the wine was then drawn with some ladles or cups like the kyathos, of typically Etruscan style, halfway between a cup for drinking and one for drawing.

The grater also belonged to the symposium supply, which was used to grate spices, roots or probably (as happened in the Greek world) cheese. From the crater the wine was then drawn with some ladles or cups like the kyathos, of typically Etruscan style, halfway between a cup for drinking and one for drawing.

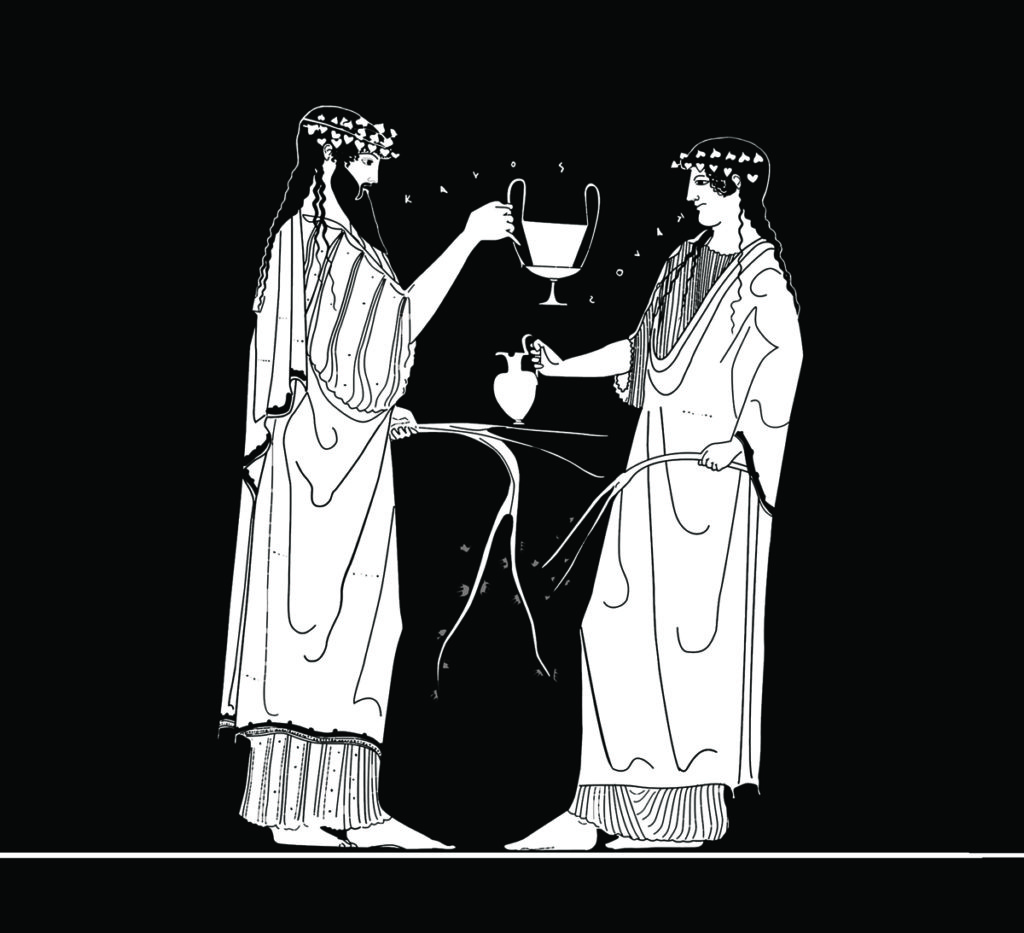

The wine was poured into service jugs (oinochoe, another original Etruscan shape) or directly in the cups of the guests. It was also filtered with a strainer to eliminate turbidity.

To drink, the Etruscans used different ceramic cups, as the simple calyx (called thavna). An imported shape was the kylix (in Etruscan: culichna). The kantharos had two high handles (in Etruscan: zavena).

Wine was linked to the religious dimension not only in consumption at funeral banquets or in sacrificial rites.The Etruscans considered control over the cultivation of the vine so crucial that the augurs, the priestly class, were the custodians of knowledge concerning the working of the vineyards, the determination of the orientation of the vine-rows, and the magic rituals to ward off bad weather. Pruning too possessed a high symbolic charge. As a form of control and regulation of the vine’s crop, the Etruscans connected it with personal worth and kingship. The pruning knife found in Iron Age tombs between Novara and Verbania represented not the tool itself but ownership of vineyards. Virgil, in describing the Latin ancestors of Augustus’ lineage, names Sabinus and identifies him as a cultivator of vines.

Etruscan magical practices were saved in Roman epoc, for exemple during the Vinalia Rustica, festivals celebrated in August 19. The August festival featured rituals and magic practices aimed at warding off any weather disturbances that might threaten the harvest. As an example of these practices, Pliny the Elder, in his Natural History, mentions the placing among the vines of an artificial cluster of grapes, which was intended to attract to itself damaging influences and thus save the rest of the crop. On the same day, the priest of Jove, the flamen dialis, celebrated the auspicatio vindemiae, and Cicero cites the auguratio vineta, rites meant to ensure a good harvest. Cicero, in his De Divinatione, attributes the origin of this “scapegoat cluster” to Attus Navius, who was of Sabine origin and a famous augur in the time of Tarquinius Priscus. When Attus Navius was a young swineherd, he lost one of his pigs and promised that if he found it, he would give to the god the largest cluster of grapes from his vineyard. Upon finding the errant animal, Attus Navius stood in the centre of his vineyard, divided it into four sections in accordance with directions in the Disciplina Etrusca, and then interpreted the flight of birds he observed. Since the birds gave inauspicious indications for the first three areas, he searched in the fourth section and found there a cluster of wondrous size.

There was two Etruscan divinties connected to the vine and wine:

TINA/TINIA/TIN. He was the highest Etruscan divinity; his primary attribute was the thunderbolt. Tina was not solely a god of the heavens; even in the beginning, he was linked to the plant world, and in particular to the culture of the vine. Pliny tells us, for example, that in Populonia there was an image of Tina sculpted from a large vine trunk. Later, he was assimilated to Zeus/Jove. In Rome, the festivals preceding the harvest were dedicated to Jove.

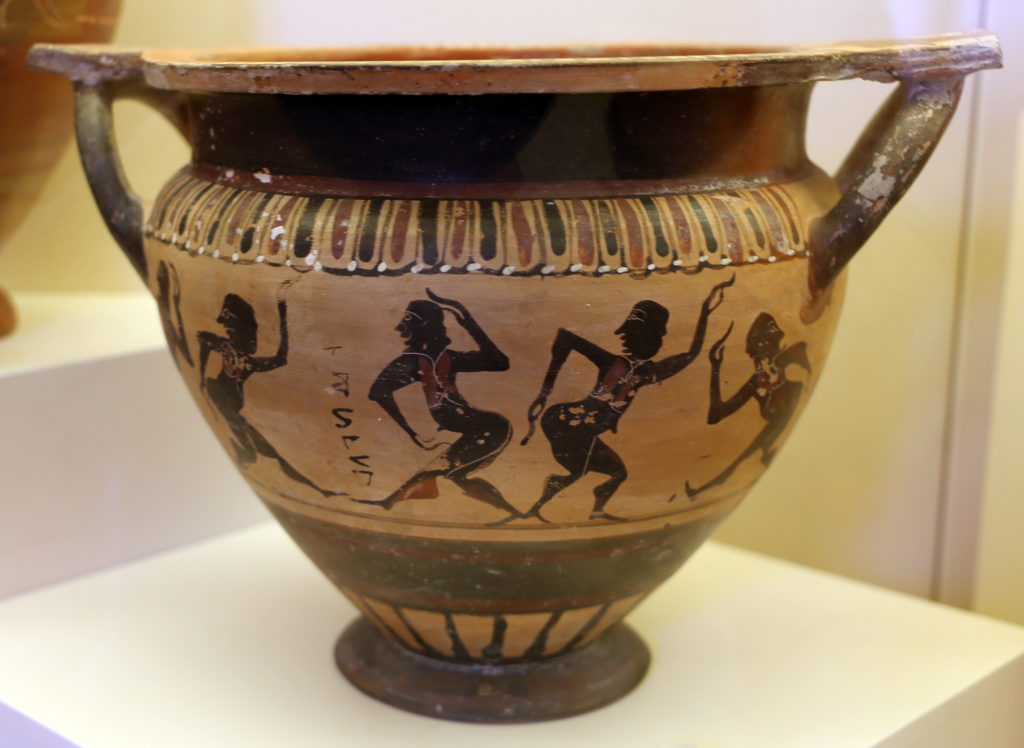

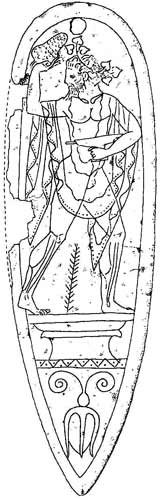

FUFLUNS was an Etruscan god, whose name is connected to the root puple, or young shoot, the same term from which the name of Populonia (Pupluna, Pufluna) derived. From the mid-6th century on, Fufluns took on the iconographical traits of the Greek Dionysos, who, under the epithet Dionysos Bakchos, gave rise to the Latin Bacchus. The artistic representation of Fufluns followed the figural canons of Dionysus: the kantharos, or drinking cup, and vine shoots, or parading with maenads and satyrs. Beginning in the 4th century, the identification became even more pronounced. The god was represented as a beardless youth, and the legends from the Greek myths were incorporated: his birth from the thigh of Zeus, his infancy at Nyssa, his encounter with Ariadne, etc.

THE DIONYSIAC RITES The influence exercised by Greek culture brought about as well the introduction into Etruria of the Dionysiac rites. This cult reached the apogee of its popularity in Etruria in the 4th-3rd centuries, so much so that colleges of Bacchantes were organised. Livy argues that it was precisely from Etruria that the Dionysiac rites arrived in Rome, which were subsequently prohibited by the Senate in 186 BC, as injurious to public order and morals.

These rites have often been misunderstood as simple sexual excesses and wild behaviour. In fact, Greek philosophy believed that wine unleashed a liberating and stimulating power in its devotees. The ecstasy that is achieved at the apex of Dionysiac frenzy is a form of higher awareness, and a means of uniting oneself with the divine. Wine was defined as “nectar of the gods” because it was considered a true and effective symbol of the sacred.

Nevertheless, the gift of Dionysus was ambiguous. On one hand, it unleashed vitalistic energy, but on the other, it induced a frenzy that could lead to death. Dionysus himself is thus a contradictory divinity, a god of vitalistic inebriation brought on by wine, but also “terrible for his irresistible power” (The Bacchants, Euripides). Dionysus is a saviour god, in fact, having been “born twice, descending to the underworld and returning hence alive.”

“mortem moriendo destruxit, vitam resurgendo reparavit”

In this way he reaffirmed life by means of death. Wine represented this death and resurrection of the god, since the juice of the grape was killed by the fermentation but then regenerated itself as a beverage with higher powers. For this reason, the sacred fury wine unleashed did not represent chaos, but opened to the cosmos, that is, to life over death.