So far, we have learned to know the Etruscans and their viticulture, based on the “married vine”. Now let’s talk about wine production.

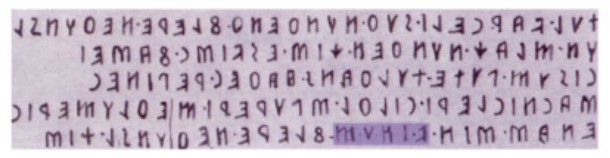

As for viticulture, even when we talk about ancient winemaking in Italy, we only allude to Roman wine. Yet the Romans also learned also winemaking from the Etruscans. The word vinum, wine, is passed to the Latin from the Etruscan. It then has remained in modern European languages (Italian and Spanish vino, French vin, English wine, German wein, etc.). However, its origin is even older and it comes from far away. It seems to be a sort of “traveling word” that most likely followed the same historical-temporal path of the vine and wine, from East to West:

winuwanti in ancient Licaonia (Caucasus)

wnš / wnšt in ancient Egyptian

wo-na-si or wo-no in Mycenae

foinos-voinos in Aeolian dialect

vinom in faliscan (ancient language of the Falisci, who lived in the southern part of Etruria, between the Cimini mountains and the Tiber river, in the area of present-day Civita Castellana)

vinum in Etruscan and then in Latin.

The current Georgian (Caucasus) gwino marks the starting point.

The Etruscan word vinum therefore derives from a foreign influence, from Greek culture. It is therefore thought that it came into use only from the 8th century B.C. There is a native word for this drink: temetum. This belongs to the protohistoric roots of the Etruscan and Latin peoples. However, the word vinum will be the winner.

After this linguistic digression, we come to our point.

How did the Etruscans make wine?

It is not easy to answer this question. We know some things for certain, we can deduce others by affinity from other Mediterranean peoples. We can surely get a lot of information from Roman authors. The productive techniques of Archaic Rome tell us much about Etruscan oenology.

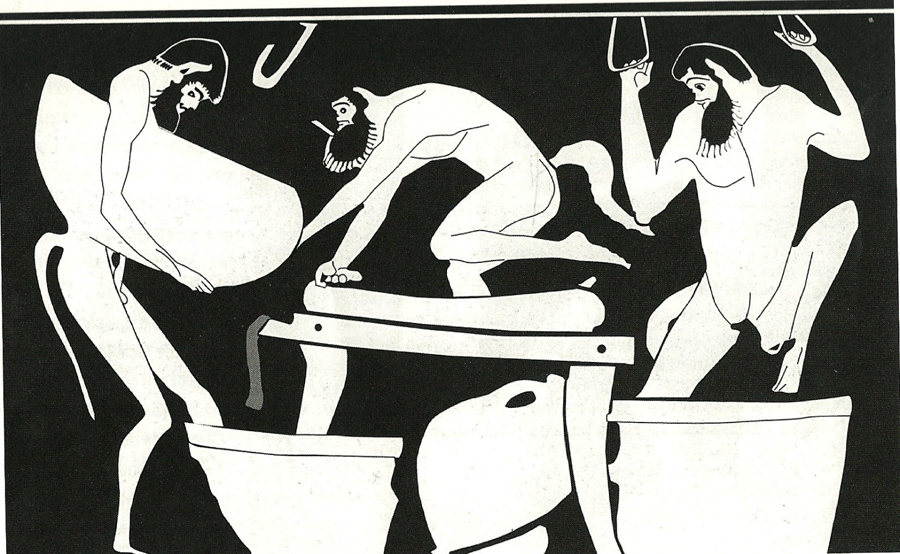

In very primitive times, in general, scholars hypothesize that grapes were crushed in small containers, simply squeezed by hand or using stones as pestles.

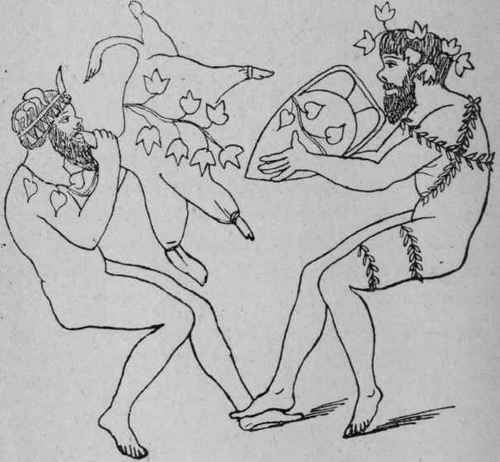

However, when the man began to represent the scene of vinification in frescoes or on found vases, the use of pressing with feet in larger containers prevailed already.

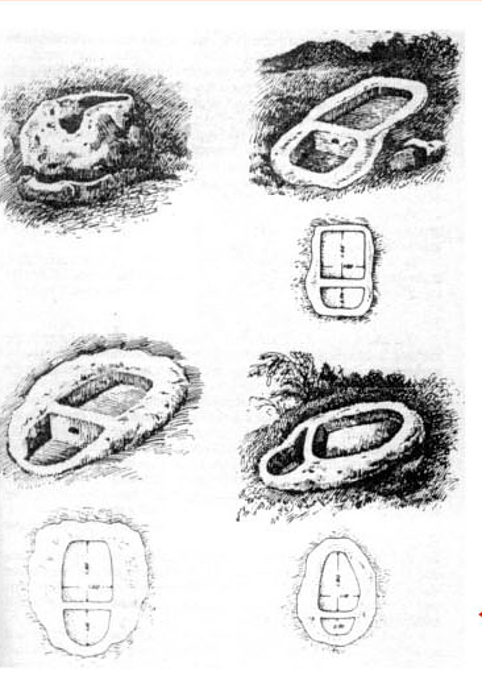

We know for sure that, at a certain point, the Etruscans began to crush the grapes into rough vats carved in the stone, called PALMENTI (the singolar is palmento). They were dug into natural rocky outcrops. These vats, before the vine domestication, were realized near the wild vines in the woods. With the beginning of cultivation, the palmento was made in the vineyards. It was probably covered with light structures, made by canes or other, to shade them or to protect them from light rains. We know it because four holes were found in some of them, also dug into the rock, as bases for housing the support poles of a canopy.

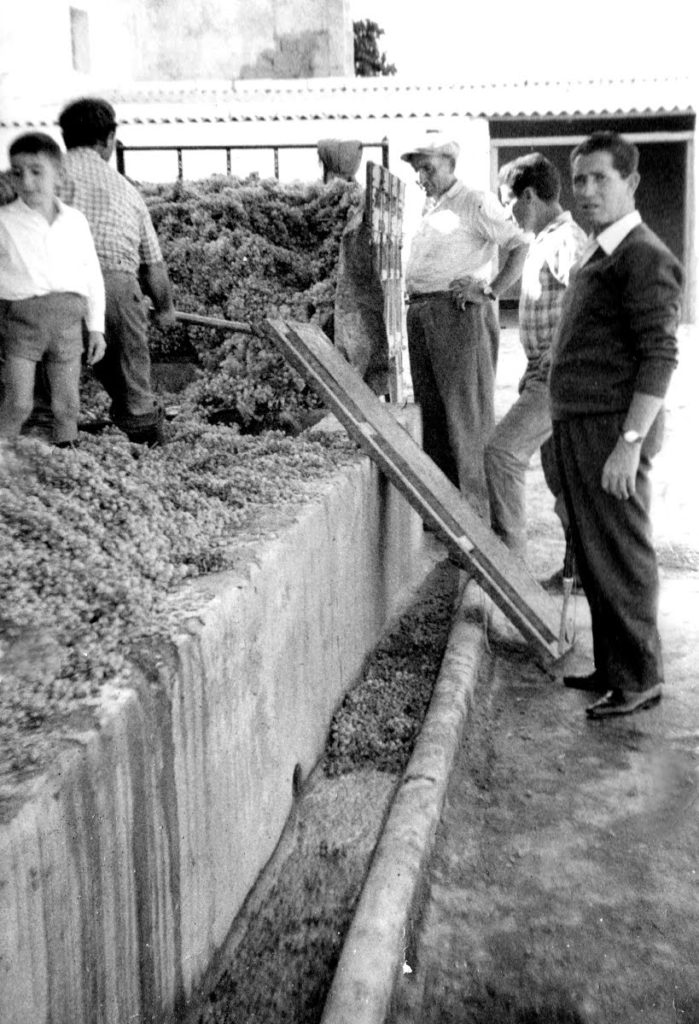

It is thought that stone vats appeared more or less from the first millennium BC. Rare examples date back to the Bronze Age but they become more numerous later. Their dating, however, is not simple, because they were also used for centuries. In Italy, many ancient palmenti were been used by local farmers until the Middle Ages and, sometimes, even later, some even up to the mid-twentieth century.

The stone vats have been found in Tuscany, in the Marche, in Latium, in Campania, in Calabria, in Sardinia, as well as in almost all areas of the Eastern Mediterranean. They have also been found in the countries of the Western Mediterranean (such as Spain, Portugal and southern France) but these date back to Roman colonization.

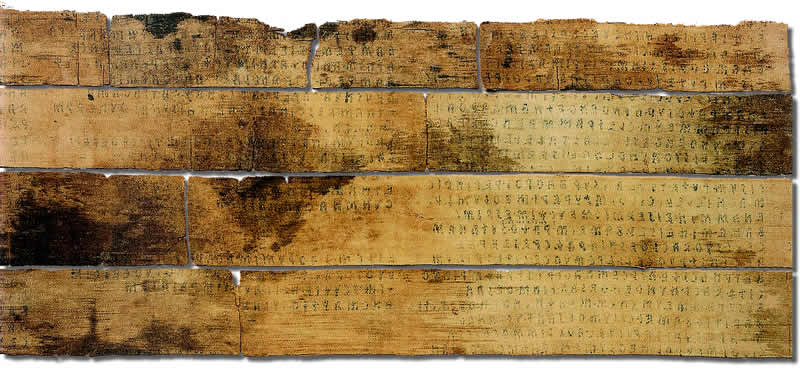

On the other hand, except for rare exceptions, they are missing in the Greek colonies of southern Italy. It is thought, probably, that wooden containers were more used in this area, of which obviously there are no traces left. This system was the one most used also in the mother country. Infect, from the numerous harvest scenes on the vases, it is clear that in Greece, in archaic times, transportable wooden vats were mainly used, with legs, positioned directly in the vineyard.

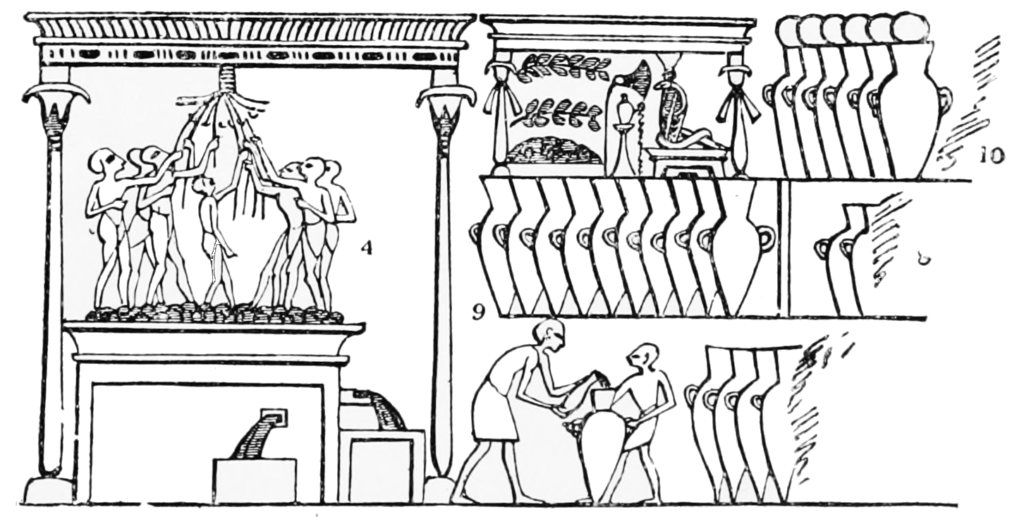

In Crete, in the Bronze age, the depictions show the grape crushing with the feet in species of ceramic vats. Also in Magna Graecia there is evidence of lime-covered clay vats. Similar constructions, made with raw bricks, are also found in the Phoenician-Punic world and in Egypt.

Returning to the Etruscan stone vats, these were dug inside rocky outcrops composed by easily workable material, often of volcanic origin, such as peperino or tuff. These materials are very perishable by erosion; they were been the cause of the loss of mostly of the ancient palmenti, became over time unrecognizable.

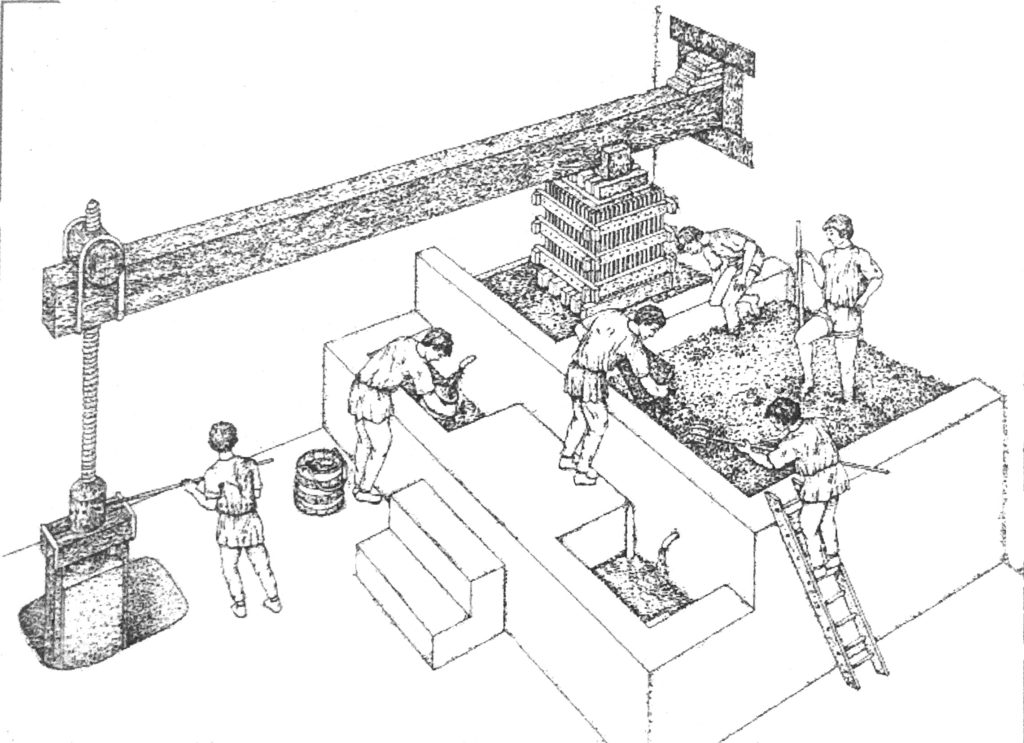

The palmenti were formed by a cavity or, more frequently, by two, communicating through a drainage channel. The grapes were crushed with bare feet in the upper vat. This is (more or less) square in shape and not too deep, with the drainage channel closed with clay. The crushed grapes were left to rest. Then the communicating hole was opened and the liquid was left to filter in the vat below. This second vat was deeper and smaller, often semicircular. Here fermentation was completed. The must could also be transferred and fermented in terracotta amphoras, those that the Romans will call dolii (dolium, in the singular).

The pomace, left in the upper tank, was crushed to recover the must-wine contained. The most primitive systems were based on the squashing made with stones or pieces of wood resting on. Later, probably, grapes were squeezed in sacks. At the end, the pomace was washed with water, producing a very light wine for the lower classes (the Romans call these wines deuteria or loria; this practice will remain common until modernity).

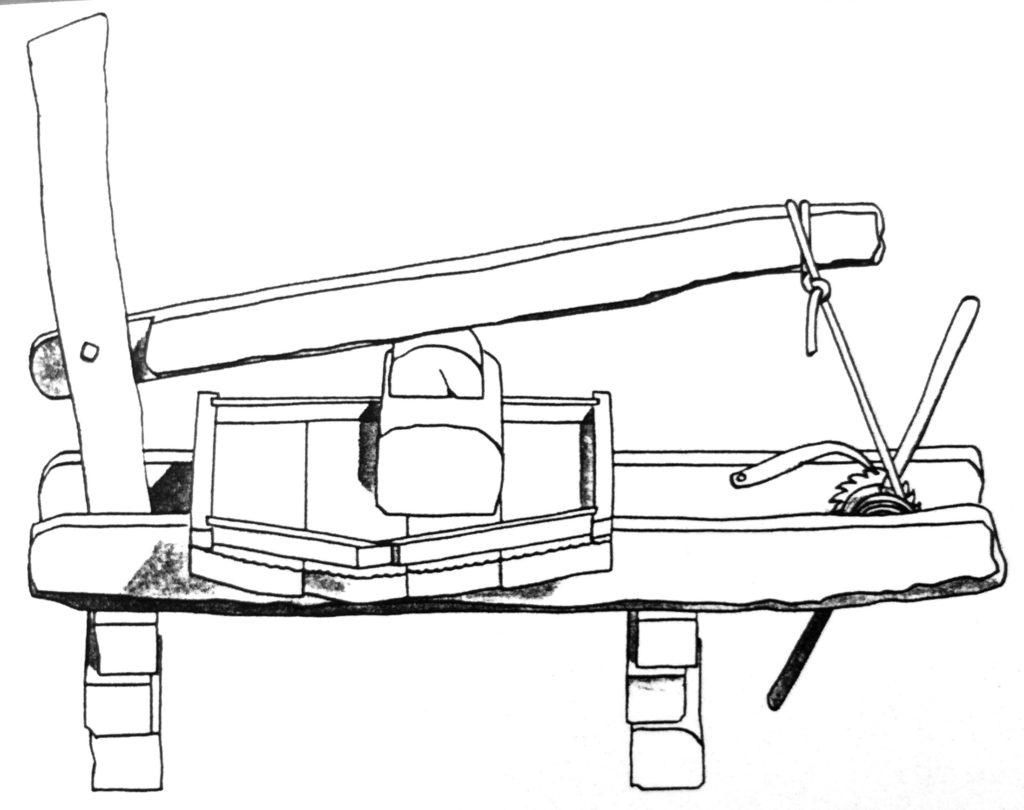

In Greece, rudimentary wine presses are documented on amphorae from the sixth century BC. They are made by a trunk lowered by human force or weighed down with stones. It is impossible to find remains of these presses, because they are made of rough materials (stones) and perishable materials (wooden parts). However, it can be assumed that they were also used by the Etruscans, by themselves or for Greek influence. However, the first documentation of similar wine presses in Italy is due to Cato, in the II century B.C.

The wines were kept in terracotta containers, like most of the products in the ancient era. Very probably also wineskins were used, of which there are no remains, but which are often depicted.

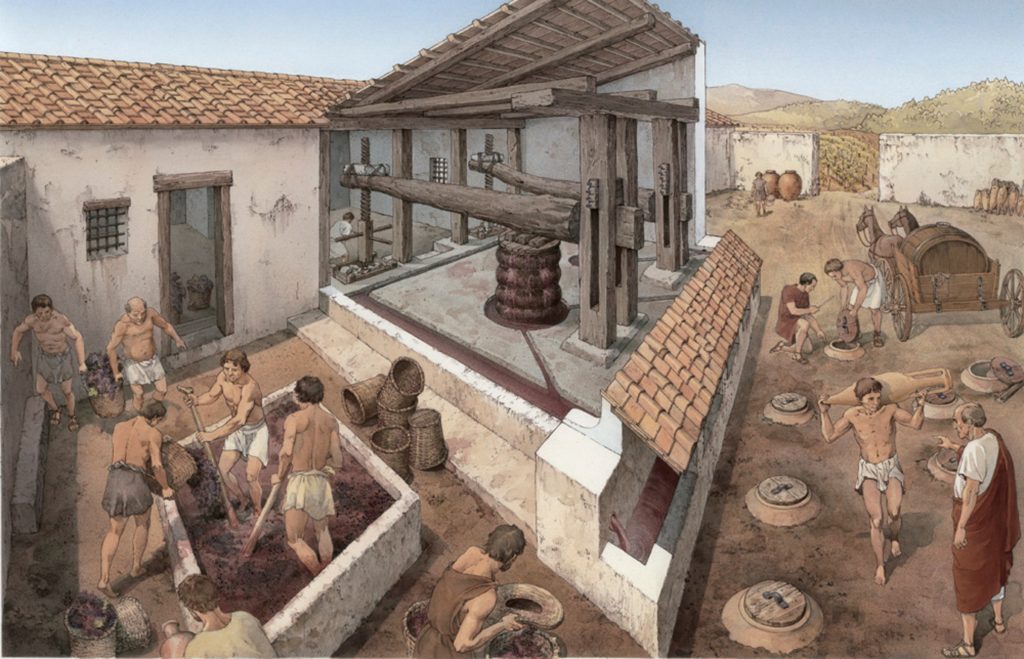

In successive epochs, the passage towards a more evolved wine production is marked by the realization of the palmenti directly in the farms. Meanwhile, Etruria was gradually annexed by Rome, in a period ranging from the 3rd to the 1st century BC. From the late Republican age onwards, the methods of wine production in Italy are widely known and documented by Roman authors.

At this stage masonry vats appear, which will remain typical of many parts of Italy, almost to the present day. They were made of stones or bricks cemented with mortar and then plastered with waterproof mortar. The grapes were pressed with the feet and the must was left to settle. Then it was fermented in cisterns in masonry or in amphoras (dolii), lined internally with pitch. In all these ages we cannot exclude the use of wood, of which no traces remain.

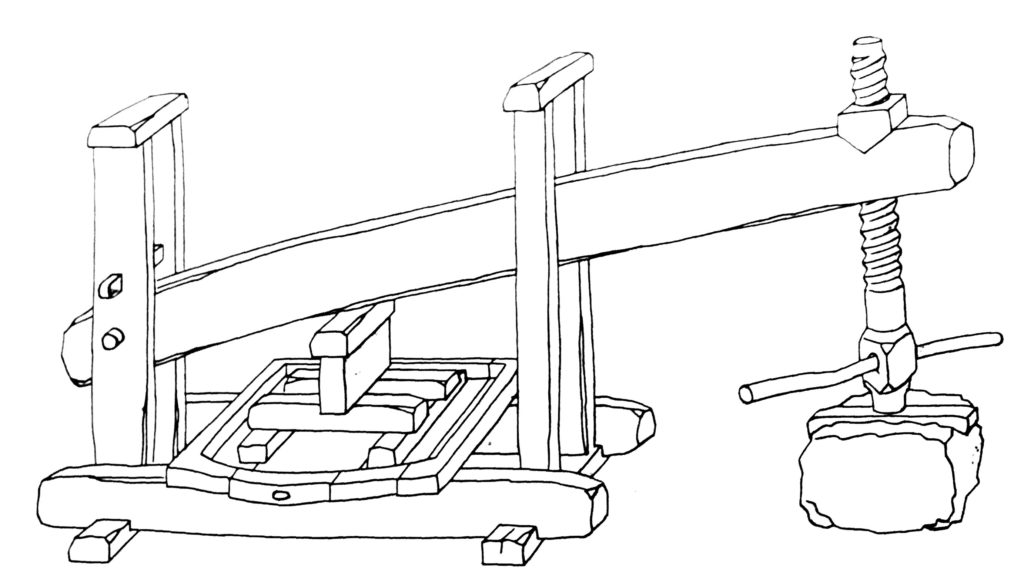

The first wine obtained from the harvest was usually consumed immediately, while the remainder was poured into terracotta containers with the internal walls covered with resin or pitch. The wine was left to rest, foaming frequently; it was decanted in spring and poured into transport amphorae. The pomace was squeezed into lever presses, operated by ropes pulled by a winch. In the largest farmers, from the first century BC, there were also large presses with lever and screw, with big stones that served as a counterweight.

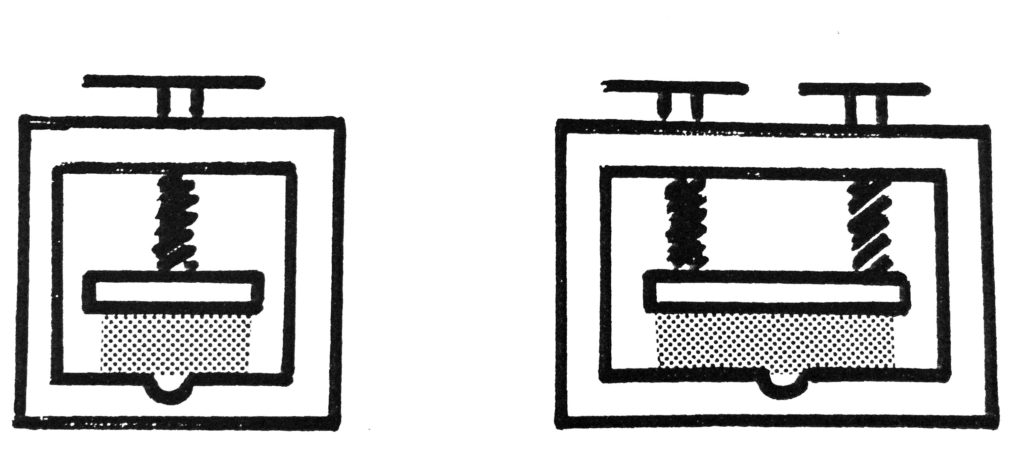

From the 1st century AD the central screw press was invented, safer and more manageable than the lever one, even if less powerful. It was made entirely of wood and therefore there aren’t remains of the ancient era. We have this information from documents, especially from the testimony of Pliny (Naturalis Historia). For this reason, it is also called “Pliny’s press”.

The Pliny’s press will make a remarkable leap only when it will can pass from the wooden gears to iron ones, which will happen only in the second half of the nineteenth century. In Roman times and in those to follow, iron was a very expensive material (without considering the technical difficulties of threading it regularly). No one would have thought of using iron where wood could be used. Only in the nineteenth century, thanks to the greater availability and the lower cost of the metal, its used began for the gears and then for the whole tool, allowing the definitive abandonment of the bulky (and difficult to handle) lever presses.

The wine production technique of the late empire will be the one that will remain substantially unchanged in Italy (and other areas of the Empire) for centuries to come. The various systems explained so far coexisted, some very archaic and others very advanced. We can imagine the great landowners who has made themselves build avant-garde and very expensive wineries. They could be imitated by local notables, but certainly not by other small farmers, with fewer financial resources, who continued to produce wine with simple tools, easy to produce by themselves.

Summarizing, the grapes were pressed with the feet in stone or masonry palmenti. Must was fermented in masonry tanks or, above all, in terracotta dolii. In this era, more and more wooden containers (documented) appear for crushing, fermentation and transport, which will become prevalent from the Middle Ages onwards. The pressing was done in the various types of wine presses described above, but mainly with lever presses with ropes and winch. Although this was an outdated technology, it remained the most widespread because it was the simplest and least expensive. The most modern systems of lever-screw or central screw presses, on the other hand, required skilled craftsmen to make them and quality timber, so they were only present in the richest wineries.

From the Middle Ages on, these same systems will remain. Almost all the terracotta containers will disappear and the wood will prevail. The palmenti and the different types of presses will remain. For substantial changes from these models, we will have to wait until the nineteenth century.