We want undestand at how climate change affects wine, what changes it can bring to wine-producing areas, and why it is best to avoid easy but unsustainable choices.

Until the end of the 20th century, hardly anyone gave much thought to the possibility that the climate of wine-growing regions might change. However, changes have become evident especially since the second decade of the 21st century. The wine world has therefore begun to ask serious questions about its future.

Climate change affects wine since the characteristics of this product are shaped in important ways by the climate and seasonal patterns of the territory where the grapes are grown. It is precisely seasonal temperature changes that determine the phases of the plant cycle. In addition, temperature has an important influence on the ripening of the fruit, determining wine organoleptic characteristics and balance. Finally, the right availability of water also plays a key role in good wine production.

In fact, already in the past the climate changed considerably, leading over time to the shifting of areas of grape coltuvation. However, these are eras far removed from us, of which we have not preserved a historical memory. In Etruscan times and the early centuries of Rome, the climate was much colder than it is now: they were coming out of a small ice age. Temperatures then rose, and in the imperial era they entered a very warm time, during which viticulture expanded greatly, spread to higher altitudes, and was also taken to regions of northern Europe. In the late Roman Empire, the temperature dropped again, with agricultural crises exacerbating political instability. This was followed by the medieval warm period, with a major new winegrowing expansion, later scaled back by the Little Ice Age, which brought famine and epidemics throughout Europe. Temperatures then gradually returned upward, more or less stabilized by the second half of the nineteenth century. Our historical memory more or less stops at this period, which by the way is when modern viticulture began to take shape.

By now it is clear that climate change is proceeding in an inescapable manner. In the vineyards it has led toward a gradual increase in average temperatures. There is a decreasing availability of water in the summer period, although in different ways in different areas. Conversely, in spring there are often extreme phenomena of heavy rainfall, causing erosion problems or actual flooding, sometimes accompanied by hail or late frost. These changes bring inevitable modifications, some for the future but several should already be introduced now.

The water problem

The higher temperatures of climate change and long periods of drought are resulting in lower water availability for several Italian territories. Hot weather worsens drought, affecting greater evaporation of water from the soil and greater plant loss through transpiration.

As a reminder, the vine is not a very demanding plant when it comes to water. It is a Mediterranean plant, so it does not need large amounts, in fact it fears stagnation. Excess water can compromise its survival. However, it must have enough at certain key moments in its cycle. A high and continuous availability of water does not lead to the production of great wines. It has always been said that slight water stress is important in the production of red wines, especially at certain stages of fruit ripening. This phenomenon has been explained with scientific studies: light water stress reduces the size of the berry, thus increasing the accumulation of polyphenols in the skin and positively affecting aromatic expression, especially in aging wines. For white wines the situation is more differentiated by variety. Stress however should be much more limited, otherwise there are more harms than benefits. In general, water stress must still be moderate to bring benefits, otherwise the benefits are lost and there is a major drop in grape quality. The availability of sufficient water, in fact, is the most important limiting condition of viticulture in Mediterranean or warm climate territories.

It may sound absurd, but in recent summers there have been more stress problems in certain parts of the north of Italy than in the center and south, albeit that it has rained even less here. Sometimes, we can see vines that are doing well and others in water stress in the same area, like the one in the image above. Why?

Because several essential factors take over, which we will try to analyze below. The first is the water capacity of the soil, that is, the ability to supply enough water to the vines when it is needed. This can also be very different among vines in the same area, even neighboring ones. The second factor is the vine’s adaptation to growing situations. If a vine has grown for years in an environment that has provided it with a good water supply, it has adapted to this situation. When periods of drought occur, it is not “ready” to deal with them and suffers much more than vines that have always lived in more limiting conditions. Then there are other factors, such as the choice of unsuitable varieties or rootstocks, inappropriate cultural practices, etc. We will take a closer look at all these aspects below.

In any case, the simplest solution that is always put forward for increasing aridity is irrigation. Unfortunately, it may be the extreme solution, but it would be to avoid it as much as possible. In fact, it is an entirely unsustainable choice. Water is an increasingly precious resource, and in the future we will have to think about saving more and more of it for essential needs. We cannot think of using it continuously to produce wine, which, although it gives us pleasure, is not an essential food.

Vineyard irrigation is not part of Italy’s historical viticultural culture, while it is already widely used in the countries of the new wine world, where vineyards were often made in places not suitable for viticulture. Already here we see the negative effects of these choices dominated by capitalist market logic. It is unethical to see farms (which produce nonessential goods) consume a lot of water when the local population lacks it for the most basic uses. This is not the case in Europe for now, and we would not like to see it happen in the future.

The most sustainable solution, although more time-consuming and complex, is to work on the judicious choice of places to make vines, on the choice of the most drought-resistant varieties, clones and rootstocks. In addition, it will become increasingly important to learn the best viticultural practices for these conditions. Let us now briefly look at these different aspects.

Rising temperatures and the choice of varieties

In regions with a long viticultural tradition, vintners have understood over the centuries which varieties were best suited and which viticultural techniques were most appropriate for their area, finding an optimal balance between productivity and quality. If climatic conditions change, past choices will have to be revised.

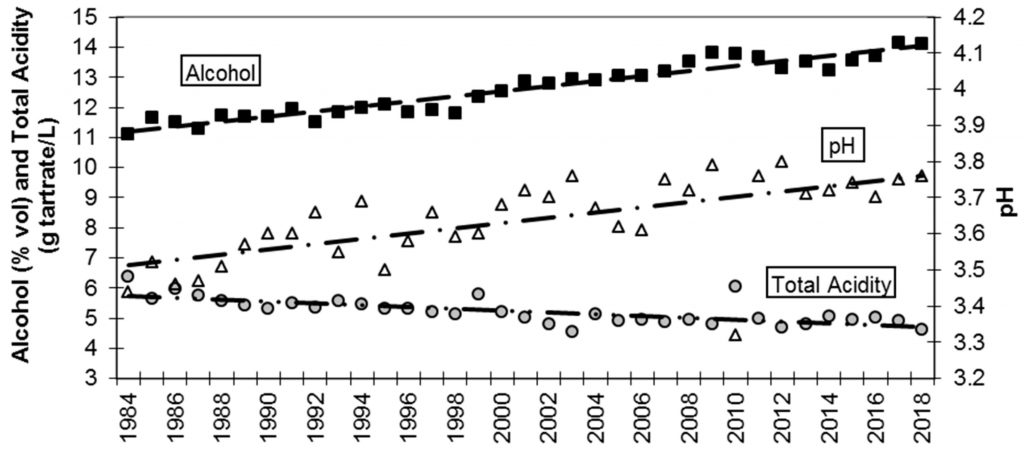

In fact, each variety has a preferential adaptation toward certain climatic conditions. Some have proven to be better than others for a given territory. This means that they manage to ripen optimally, expressing a good balance in the ratio of sugar to acidity as well as for the aromatic and polyphenolic component. Lack of balance in cold environments leads to the production of wines that are too acidic, sharp and vegetal. the worst risk in warmer climates , if there is no balance, is to have wines that are too alcoholic, flat and heavy, not balanced by freshness. There are few aromas, most of them “cooked.” In between these two extremes is the infinite scaling of situations that leads to the production of wines with different sensory characteristics. The trend of climate change is toward warmth, so the risk is mainly related to the loss of freshness and aromatic complexity.

L’alterazione di questi equilibri dipende da diversi fattori. I cambimenti di temperatura stagionali influiscono sulle fasi del ciclo della vite, alterando tutti le fasi, soprattutto le tempistiche della maturazione. Inoltre numerosi studi hanno ormai dimostrato come la temperatura ha effetti diretti sulla maturazione. L’eccesso di calore nel periodo estivo porta ad alterazioni dei processi metabolici che avvengono durante la maturazione del frutto, come ho già raccontato in precedenza qui.

If there is an increase in temperatures, the phases of the vine cycle tend to speed up. This can result, for example, in earlier sprouting. This can be a problem in territories at risk of spring frost. The risk increases especially if you have susceptible varieties, such as Sangiovese or Nebbiolo.

A climate that becomes warmer results in changing the timing of grape ripening, risking taking certain varieties out of the optimal ripening time window for that particular territory. In our hemisphere, it has more or less been seen that the ideal harvest window is from early September to the first half of October, with variables related to individual territories (as well as to the production of particular wines). On average, this window is identified by jamming together two basic needs:

1. the best time for the grapes to have sufficient time for slow and gradual ripening so that they have a good balance,

2. that the weather conditions at harvest time remain good enough not to affect the quality of the fruit.

If the environment is too warm for a given grape variety, all the stages may be too fast, ripening becomes too early, not allowing the fruit to accumulate in a balanced way all the substances that lead to the birth of a good wine. Conversely, if the climate is too cold for a grape variety, it can take too long. In this case, the risk is that sufficient ripeness may never be reached before temperatures begin to drop, thus stalling the process before its conclusion. Or ideal ripeness might be reached at times when weather conditions deteriorate significantly (thunderstorms, hailstorms, etc.), making it very difficult to harvest good grapes.

In European territories with a very long viticultural tradition, as Italy and France, the selection of varieties that we now consider “historic” or “native” actually took place mainly between the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. The criteria for selection were related to the climatic conditions of those periods. As the climate changes, the selection criteria will also have to change. Speaking very generally, in the past, when temperatures were cooler on average, the most productive grape varieties were favored, with early ripening times and high sugar accumulations. As temperatures rise, we will have to fall back on varieties with opposite characteristics: varieties with later ripening, more acidic and less sugar accumulation.

In the Old World we have a huge historical reservoir of grape varieties that can come to our aid. Many of the varieties that were little used or abandoned in past centuries, because they were not suited to the climatic conditions of the time, can once again become important resources for today and tomorrow. Absurdly, there may be more problems in New World countries where, although there are generally no restrictions on the varieties to be used, a much smaller number of grape varieties are actually used, with no knowledge of all the others.

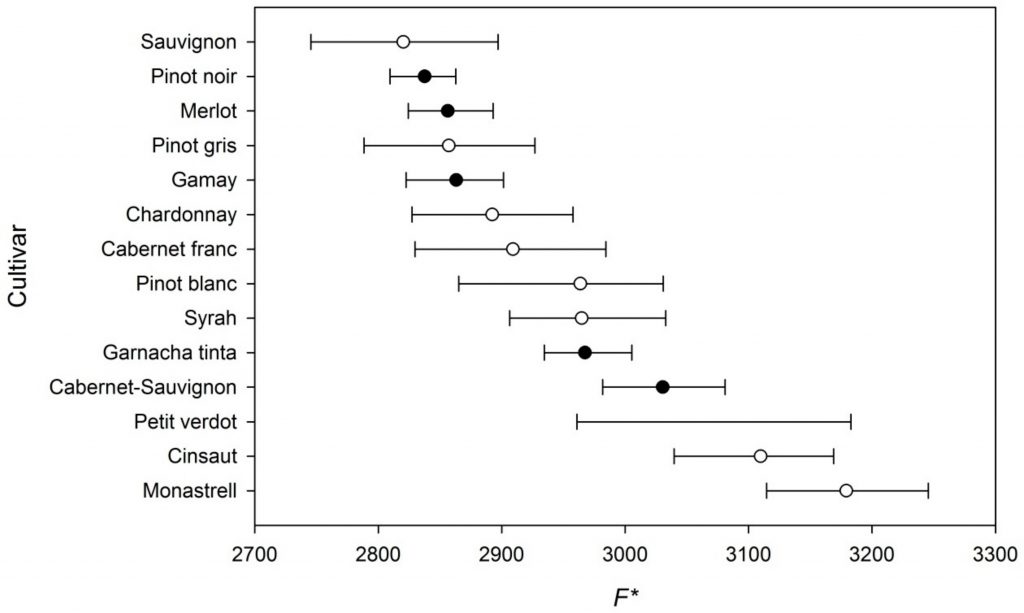

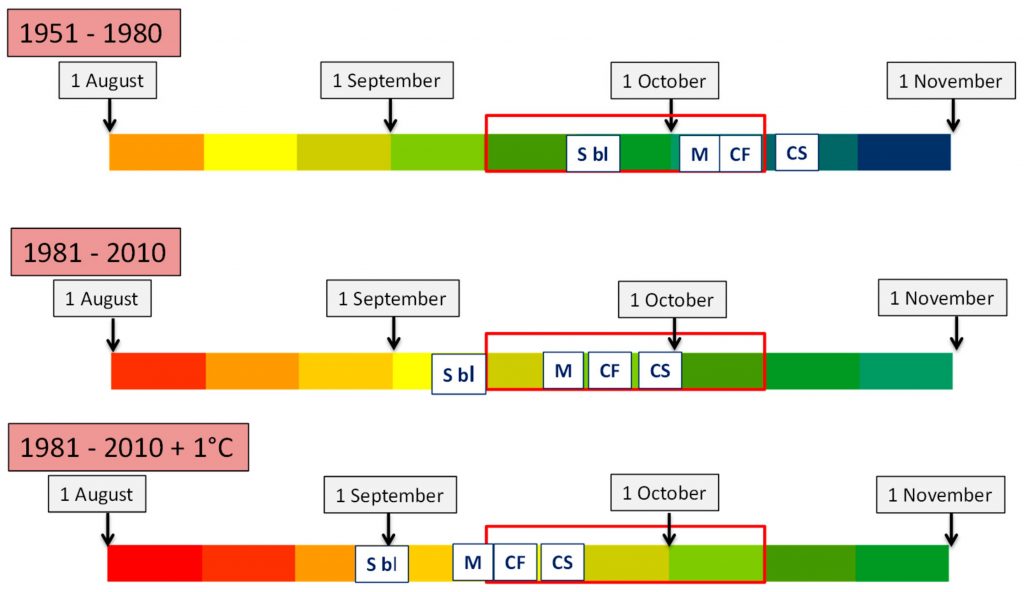

For example, one of the varieties seen to be suffering the most from climate change is Merlot. In particular, it is watched and studied with concern in its original region, Bordeaux. In the study whose results I report below, an attempt was made to understand how the harvest date has changed over time in Bordeaux for different varieties. In the following graphs, the following are indicated by initials: the Sauvignon blanc (S bl), Merlot (M), Cabernet franc (CF), and Cabernet sauvignon (CS). The first line indicates the average harvest period for each variety in the years 1951-1980, the second for the years 1981-2021, and the third for the often period (1981-2021) in a slightly warmer zone (registering +1°C compared to the previous one). The colors indicate the average temperatures for the period: ranging from red indicating warmer temperatures to blue for colder temperatures. Comparing the three rows, you can see how the variety boxes shift: the harvest is getting earlier for each variety. The red box highlights the harvest time window considered the best for the area, the one with the optimal temperatures. As can be seen in the graphs, several varieties have already left the optimal time window for the territory, such as Merlot and Sauvignon blanc.

Rootstocks

Varieties are important but let us remember that it is the rootstock that determines the root part. Let us also remember that for plants, the most important part in mediating with the environment is what is under the ground, rather than what is outside. Roots play a central role, as I have already recounted in these two dedicated posts (here and here).

As with varieties, the choice of rootstocks has always depended on soil type and climate. Already there are rootstocks designed for drier climates. Others have been created recently, increasingly targeted for climate change. I recall those in the M series studied by the University of Milan, which were created by hybridizing with American vines native to particularly arid places.

However, it is not all solved because research in viticulture is not simple. If something works on paper or under experimental conditions, the same may not necessarily happen in the field. The variables of adaptation of a rootstock are many for each territory and micro-territory. In addition, the affinity between the rootstock and the productive variety must also be considered. Add to that the fact that to get answers in viticulture, field trials of at least a decade are needed to limit the variables related to vintage changes.

Better places fot the grape vine

The choice of where to plant a new vineyard must be very careful. It must be admitted that sometimes it depends more on reasons of convenience or economics than on a qualitative choice. However, with water becoming more and more of a constraint, it will be increasingly important not to proceed haphazardly but to do a thorough analysis to understand the water potential of the soil.

This capacity is related to several soil characteristics, particularly depth. Deep soil is capable of greatly expanding the root system of the vine. Depth refers to the part of the soil that can be explored by the roots, before the parent rock. Even in seemingly deep soil, however, there may be insurmountable obstacles that limit it, such as strongly calcareous or conversely acidic areas or rocky banks or other impediments. For example, soils with too high a clay component can become hard as stone if the summer is very hot and dry. The deeper the soil, the better the vine can expand its root system, reaching moist areas even in the driest seasons. In addition, location is important. Since (trivially) water flows downward, under limiting conditions it is best to choose foothill or valley floor soils, not steep sides. It is no coincidence that in Bolgheri or other semi-arid or arid lands, viticulture has historically developed in the low hills and lowlands.This capacity is related to several soil characteristics, particularly depth. Deep soil is capable of greatly expanding the root system of the vine. Depth refers to the part of the soil that can be explored by the roots, before the parent rock. Even in seemingly deep soil, however, there may be insurmountable obstacles that limit it, such as strongly calcareous or conversely acidic areas or rocky banks or other impediments. For example, soils with too high a clay component can become hard as stone if the summer is very hot and dry. The deeper the soil, the better the vine can expand its root system, reaching moist areas even in the driest seasons. In addition, location is important. Since (trivially) water flows downward, under limiting conditions it is best to choose foothill or valley floor soils, not steep sides. It is no coincidence that in Bolgheri or other semi-arid or arid lands, viticulture has historically developed in the low hills and lowlands.

However, soil depth is not enough; vine adaptation is also essential. As it grows, the vine adapts to the conditions in which it finds itself. If there is little water, it implements a whole series of strategies that enable it to limit the problem, such as the development of a large root system and other physiological adaptations. On the other hand, if the plant has grown by having enough water available, it does not need to develop such adaptations, whether the soil is deep or not. This is why it is usually recommended not to overwater young vines, to stimulate them to produce roots.

You will therefore have understood from these considerations why the drought of recent summers has often shown more negative effects in certain vineyards in northern Italy (or in France) than in central and southern Italy, even though the amount of rain that has fallen is not proportional. Simply because these are vines not adapted to drought conditions, so they are much more fragile to the problem. Besides all, the traditionally place for a vineyard in continental climates were that avoid water stagnation, such as steep hillsides and mountainsides, places that do not retain water. In addition, these are places that often have shallow soils. Here vines can develop shallow, modest root systems. These are all conditions for which even a not necessarily excessive period of drought can have a deleterious effect. Conversely, in the already semi-arid areas of the center and south Italy, drought can worsen, but it is a problem that vines and vintners have always been used to dealing with. Therefore, soils with higher water potential have always been chosen, and vines have grown adapted to these conditions (not to mention the choice of rootstocks, varieties, etc.).

Climate change also seems to prospect over time a shift in the historical sites of viticulture. Historically, vines have ascended and descended mountains several times as a result of climate change. In the mountains, the temperature decreases by 0.65°C for every 100 m of elevation. Raising the quote of the vineyards, if there are no other limitations (soil characteristics, water availability, exposure, etc.), has always been a way to counteract temperature increases.

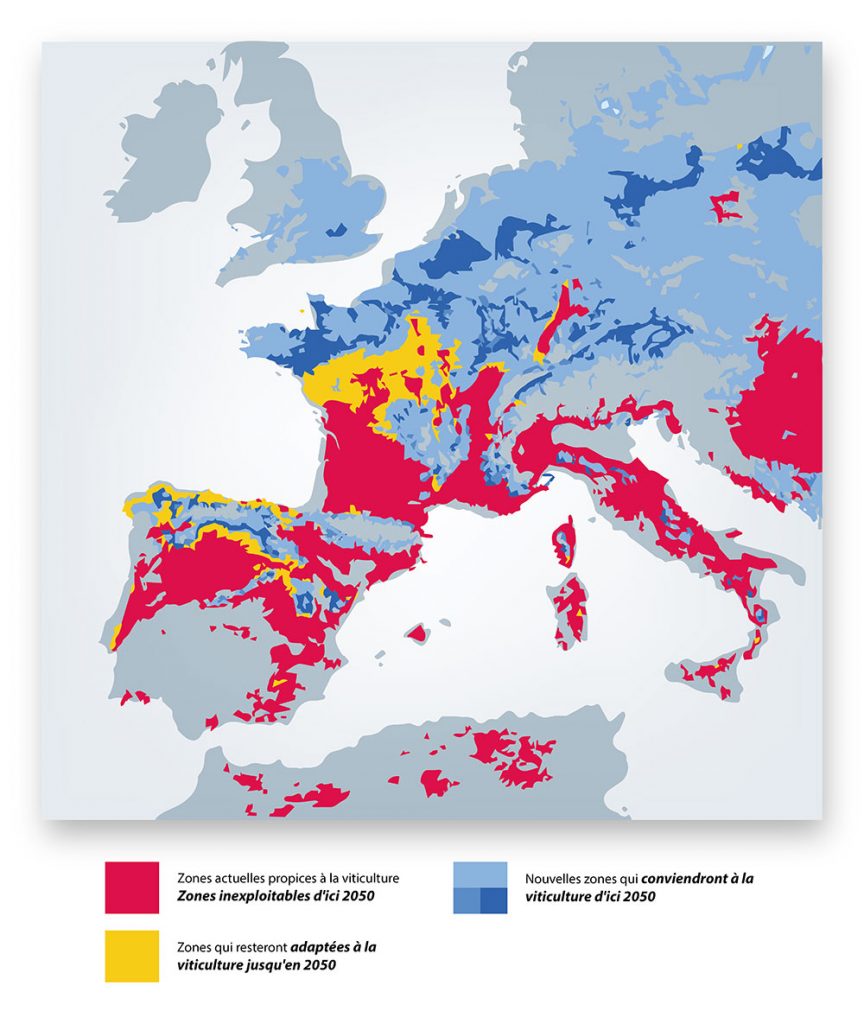

Some also fear major changes in latitude, with a future that could see the disappearance of viticulture from traditional territories and expansion into countries without tradition. It will probably happen a bit, but let’s not get ahead of ourselves. Hot periods have been there in the past as well, resulting in the expansion of production aerals to more northern areas. However, traditional countries have never lost more ground. It will also depend on the vintners, how committed they are to implementing the necessary adaptations. Several studies, such as the one from which I took this chart, make bleak predictions for Italy’s viticultural future, although not all of them are so dramatic. Here they predict the disappearance of viticulture almost everywhere in Italy by 2050. However, Italian production will certainly undergo changes.

Changes in vine training systems and other agricultural practices

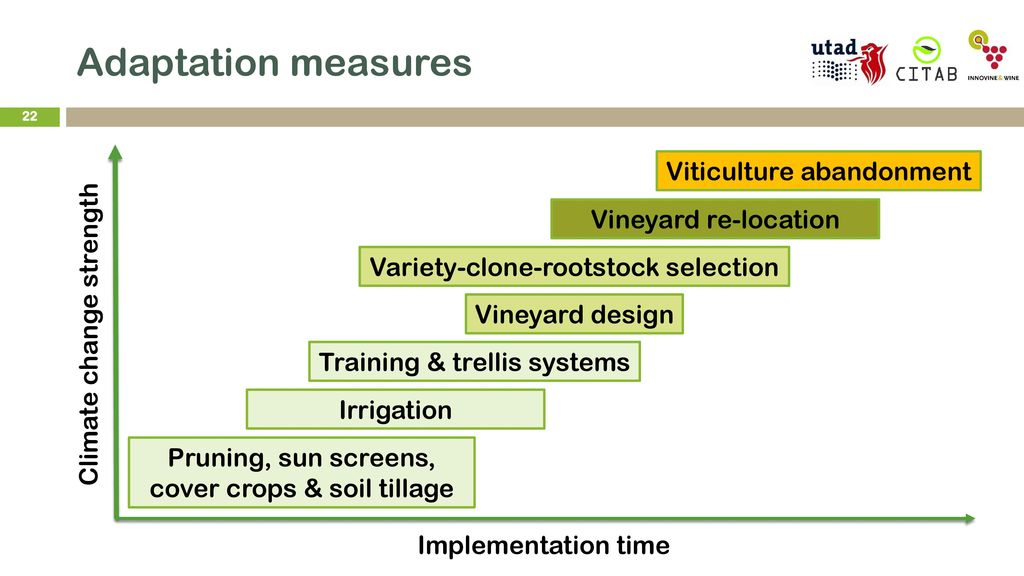

This graph (from “Modeling climate change effects on viticulture,” by João Santos et. al.) summarizes the changes that will gradually be required of an area as climate change worsens (time in the y-axis). In order, with the first signs of climate change, one should start adapting cultivation practices, i.e. pruning, bunch shading (instead of defoliation), different soil management, etc. Later or in parallel, the introduction of irrigation might be required, although, as mentioned, it is a very unsustainable option. Along with or shortly after, changes in training systems and variations in vineyard layout, such as wider spacing between vines, should be introduced. Meanwhile, it also becomes necessary to rethink varieties (and clones) in combination with rootstocks. Moving forward, there will be a need to move vines to the most suitable areas of the territory, especially when new plantings are made. Finally, if the change becomes extreme, it may lead to the abandonment of viticulture in that area.

Historical forms of vine training are many, adapted to the most diverse climatic situations and variety requirements. In modern viticulture there has been more uniformity, sometimes based on viticultural fashions or to imitate successful territories or, in the case of more industrialized production, to simplify mechanical interventions. Climate change will push us to go back to putting the choice of the best farming system first in the adaptation between variety, climate and soil. For example, research is already being done in parts of France on the advisability of returning to tall forms of breeding, which had been abandoned in many areas in favor of low ones. Trunk height also causes major temperature changes for buds and clusters, as well as changing several general aspects of plant physiology. In spring frosts the coldest air is closest to the ground, while it warms even a few degrees as it rises upward. It is no coincidence that, historically, in areas subject to frost hazards, the traditional training systems were with high vines. The opposite can happen in summer, during ripening, with temperatures sometimes very hot near the ground and dropping away from it. In a study done in Saint-Emilion, temperature sensors were installed at different heights (30-60-90-120 cm). A significantly different Winkler* index was found in the different heights, with lower average temperatures at the 120 cm height than at 30 cm above the ground. This difference results in a possible ripening delay of about 7 days.

*Winkler index: is an index used in viticulture to compare different territories or zones. It is obtained by summing the average temperature of all days between April and October (the period of vine activity)

In other pedoclimatic situations, especially where heat is associated with greater aridity, however, low forms may be the most appropriate. In fact, the breeding form that has always been most common in hot Mediterranean territories is the bush and the low systems derived from it.

One change in the vineyards that is already being talked about a lot is to go back to enlarging the spaces between rows and between vines, as in the past. Each vine thus has more space, with greater expansion of the root system and with more soil to explore in search of nutrients and water.

Modifying viticultural practices was also discussed. Those that are suitable for a warmer climate are those that are already put into practice in Mediterranean and arid areas, which I have often described. For example, the warmer the climate, the more there is a need to change all the work in the vineyard so as to raise the production yields a bit, to have a better balance of grapes, particularly to avoid too high concentrations of sugars (and consequently alcohol). Another useful practice is to shade the bunches, avoiding vine defoliation, …

Late pruning is useful for several purposes, as it delays all phases of the vine cycle. On the one hand, it delays budding so as to limit the risk of spring frosts. It also allows the period of grape ripening and harvesting to be moved forward so that it occurs in a better temperate window, that is, in a somewhat less warm period.

Scientific studies on climate change are also focusing on how fruit ripening changes by varying the size of the plant canopy, that is, the mass of leaves. Twentieth-century studies had set optimal parameters that can no longer be considered valid. For example, in a continental climate until now it was considered that to have optimal ripening (particularly good sugar accumulation) there had to be a ratio of at least 1 square meter of leaf area per kilogram of grapes. In hot weather this figure must be lowered, as is already done in Mediterranean climates. A lower ratio leads to delayed veraison, lower sugar and color accumulation in the reds, with no particular effect on total acidity.

Then there are numerous ongoing studies that are evaluating other aspects of climate change and that need further investigation. For example, it appears that higher levels of carbon dioxide lead to an increase in the optimal average temperature for photosynthesis in vines, with a lowering effect on transpiration. Some studies are trying to understand how climate change may alter soil microbiology and its impact on drought resilience by crop plants. These and other aspects will be understood over time.

What to do in conclusion

In conclusion, vintners must increasingly prepare for the effects of ongoing climate change. They should do so, however, by seeking solutions that keep this activity sustainable and not by indiscriminate use of irrigation. The grapevine is a Mediterranean plant, which does not require as much water anyway, unless it is grown in the right soils, with the right viticultural practices, choosing the most suitable varieties-rootstocks, etc. The most worrying aspect is the delay with which this seems to be being done, especially in Italy, which, moreover, is among the countries most exposed to the consequences of climate change.

The vintners should already take all this into account when making new vineyards. A new vineyard should be thinking with different criteria than in the past, considering the best location, new training systems, wider spaces between rows, different varieties and rootstocks, etc. Then the old vineyards will have to be redone over time and the necessary changes can be introduced everywhere.

However, focused studies are essential if one does not want to proceed haphazardly or with rough adaptations made by copying the choices of other more or less similar areas. Although the basic concepts may be universal, viticultural application still remains very local. Much research may be conducted by universities and research centers. However, these subjects cannot be expected to derimate the problems for each individual area, exposure and micro-climate. It becomes more and more important (although it always has been) for each winery to think about devoting some space of its vineyards to in-house experimentation over the long term, in order to prepare itself well in advance for possible ways forward.

Bibliografy:

C. van Leeuwen at al, “An update on the impact of climate change in viticulture and potential adaptations”, Special Issue “Viticulture and winemaking under climate change”, Agronomy 2019, 9(9), 514

L. Allamy et al., “How climate change can modify the flavor of red Merlot and Cabernet sauvignon wines from Bordeaux”, https://ives-openscience.eu/4870/

E. Archer and A. Saymaan, “Vine roots”, 2018 The Institute for Grape and Wine Sciences (IGWS), Stellenbosch University

Payan J-C., 2012 d’après García de Cortázar I., 2006, in Viticulture et changement climatique : adaptation de la conduite du vignoble méditerranéen.