(continued from here)

We are concluding our journey through Italian viticulture at Roman times, with the latest works from the vineyard and the harvest.

First, however, I would like to complete the picture of the time with the description of the climate. The climate changes have had great importance in the historical events of humanity, all the more so as regards the evolution of agriculture.

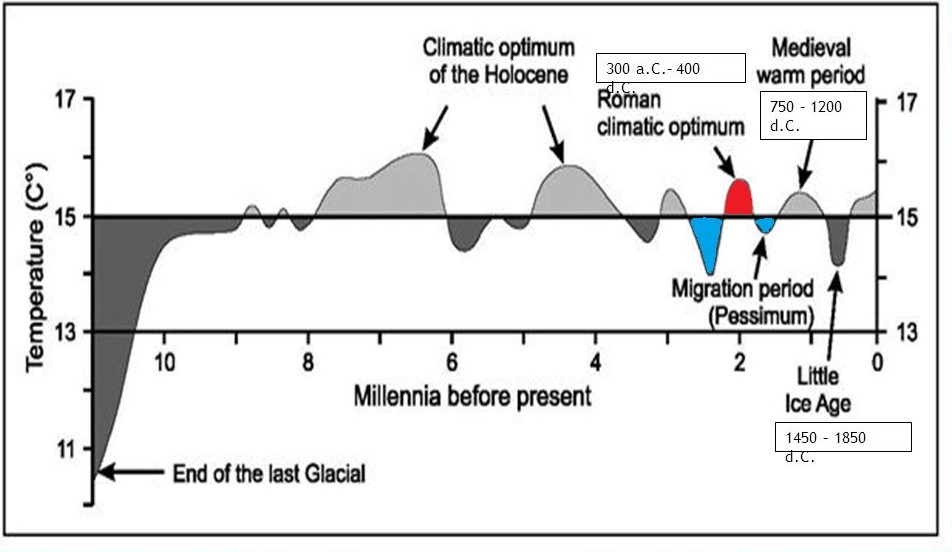

The foundation of Rome (753 B.C.) occurred in a period of small ice age (in the graph, it is the first blue descending peak), which lasted from about 900 to 300 B.C. This means that, in the first centuries of the Roman era, Italy had a decidedly colder climate than what we are used to today. The graph on the side shows the annual average temperatures from the Ice Age to today. The final vertical line represents our period.

Numerous Roman authors testify to the terrible winters of those periods. Columella and Juvenal say that, at the beginning of the fourth century BC, the winters were so severe that the Tiber was covered with ice. The woods of Latium and Etruria were constantly covered with snow. The winter of 399-400 B.C. remained in the history of Rome because of an incredible snowfall. More than 2 meters of snow (7 feet) fell. The collapses of trees and roofs throughout the city caused numerous deaths and wounded. Varro tells of very long winters in the Italian mountains. Saint Augustine reports that, still in the winter of 275 B.C., the Tiber froze and Rome remained under the snow for 40 days.

How can we imagine the viticulture of that period? We don’t have references. We can think that it was present above all in milder areas, such as the coasts or other favorable areas, up to not very high altitudes.

After that, the climate started to undergo a remarkable change, with the rise of temperatures, up to the moment called the Roman Optimum Climatic, a hot period. It lasted from about 250 B.C. to 400 A.D. and locally affected Europe and the North Atlantic. The climatic passage towards higher temperatures corresponds with the expansion of Rome in the Mediterranean. In ancient times, in fact, the sailing was possible only during the favorable seasons. The better climate allowed longer sailing periods. It also corresponds to the exponential increase in Italian viticulture. The warmer climate allowed it to expand even in areas that were previously unfavorable. Thus, the massive export of wine also began.

The increase in temperatures determined, in general, the shift to the north of the Mediterranean crops line, such as the olive tree. Pliny writes that the beech, which previously only reached the height of Rome, pushed its habitat to the north of Italy. Then, the hot period favored the spread of viticulture by the Romans in most of Europe, even in the territories that had never seen the vine before. They took the vines up to England, as well as to considerable altitudes. From many of these extreme areas, the viticulture will disappear with the subsequent Little Ice Age

Instead, a cooling period began from around 400 A.C. According to several scholars, the instability and the climate worsening, with the consequences on agriculture and people’s health, contributed to the fall of the Western Roman Empire.

It is not known exactly how much the human activity of the time could have influenced climate changes. We know, however, that the Roman era recorded the first massive human interventions on the transformation of the Italian natural landscape.

In pre-Roman times, Italy was made up of immense expanses of woods, interrupted by marshy areas in the coastal areas or in the plains. Only a very small part was occupied by agriculture, restricted around the colonies of Magna Grecia in the south or the city-states of central Italy.

For example, the vast area between Aquileia, Ravenna, Mantua, Brescia, Reggio and Como was all marshy. The Adriatic, Tyrrhenian and Ligurian coasts were covered with dense forests, from which timber, considered valuable for the size of the trunks, was taken. The hills of Rome themselves, such as the Palatine Hill or the Quirinal Hill, were covered with woods. Between Modena and Bologna, the forests were still so dense in the Republican era that they considerably slowed down the construction work of the Via Emilia. Livy says that the Cimino forest in Etruria was more terrifying than the Germanic ones described by Tacitus. The Cisalpine Gaul (north of Italy) was very rich in oaks, in fact it was the main breeding center for the empire’s pigs. The Gargano promontory, in Apulia, was covered with oaks and other trees that reached the sea.

[one_second][info_box title=”The vineyard even before the law” image=”” animate=””]

«Sed etiam a vinea, et balneo, et theatro nemo dubitat

in ius vocari licere».(Gaius, Liber I ad Legem XII Tabularum)

“It is not allowed to sue (bring to court) anyone who is in his vineyard, in the thermae or at the theater“.

This sententia, cited by the jurist Gaius, is included in the most ancient written laws of Rome, the Laws of the XII Tables (Lex XII Tabularum) (450 B.C.). It shows how important the works in the vineyard were considered in the most ancient eras of Rome, to the point of also suspend legal proceedings. They had to wait for the vintner to finish his job.

In general, the importance of viticulture in Roman period can be understood from the large number of laws that concerned it, with respect to successions, sales, legacies, etc. In agricultural contracts, it was always recognized the increase in the value of a land in which a vineyard had been made. In the event of early termination of the rental contract, also due to arrears, the owner had to indemnify the tenant farmer who had planted vines there.

There are also numerous court cases concerning the vineyard, which offer us not always edifying scenes of the life of the time. For example, the jurist Sextus Pomponius tells of a man who, taking advantage of the great luxuriance of the vines (trained to the trees) of the neighbor, collected and sale the fruits from the shoots that stretched up to the trees of his property. At one point, the owner of the vines noticed it and he wanted to cut those branches. The man opposed the cut, and he sued the neighbor to prevent it to him. However, the court ruled against him, reiterating that the branches always belong to the owner of the land where the vines are planted, wherever they go.

In ancient Rome, there was the first example in the history of a government intervention to regulate the planting of vineyards and, therefore, the wine market. In 92 A.D., the famous Domitian’s Edict prohibited the planting of new vineyards and introduced the obligation to destroy half of those in the provinces. According to some scholars, the edict was born in a moment of general stagnation in the wine trade. In particular, the Roman patricians, who were wine producers, did not want to have external competition. Cicero already had protectionist intentions when he wrote in De Re Pubblica (55-51 BC): “We do not allow the Transalpine peoples to cultivate the olive tree and the vine, so that our olive growing and viticulture remain superior“. According to others, the edict was also born from the choice to curb the excessive expansion of the vineyards that was taking place in that period, to avoid famines due to lack of wheat.

The subsequent decline of viticulture in Italy made the ban disappear and, vice versa, several emperors worked to stem this phenomenon. For example, around 275 AD, Aurelian distributed slaves free of charge to the landowners, from Etruria to the Maritime Alps, to expand their vineyards.

Instead, the ban on creating new vineyards outside Italy was lifted by the Emperor Probus, towards the end of the third century A.D. Probus finally allowed “all the Gauls and all the Spaniards and even the Britons to cultivate vines and make wine“, and to “own the vineyards to the Gauls and the Pannonians” (Historiae Aug. Probus, 18, 8). He also introduced corves for the Roman centurions, dedicated also to the planting of vines, such in Germany.

Towards the end of the ancient era, the Italian viticulture was in sharp decline also because it was oppressed by bureaucracy and ever more suffocating taxes. Cassiodorus says that the producers went so far as to cut their vines to avoid unsustainable taxation. In the Codex Theodosian Code (413 A.D.), it is written that those who cut the vines to escape the tax authorities were condemned to the death penalty and confiscation of property:

“Si quis sacrilega vitem falce succiderit, …”

If someone had cut down the vine with a profaning sickle …” Cod. Theod. l. XIII. Tit. XI. leg. 1.

The Lombards will return to write laws for the vineyards some centuries after. [/info_box][/one_second]

These woods had always been used by man but, in Roman times, the population increased considerably compared to the past and so did the technical applications. The use of timber became massive, used as fuel, but above all for the building, in considerable expansion, and the construction of the great Roman naval fleets, …

So, over the centuries, the Romans deforested a large part of the peninsula, also to make more space for agricultural land and pastures. Compared to today, however, there was still a big part of uncontaminated nature

In archaic times, the king Ancus Marcius had placed the woodland patrimony under the protection of the gods and the decemviral magistrates, declaring it Public Natural Property. More than a protection, probably, it was only an economic question: an important part of the public income derived precisely from the management of this patrimony. However, we know that the Romans themselves noticed the degradation that ensued from the intensive exploitation of natural resources. Pliny and other authors tell us about it, talking about landslides, floods, erosions, water shortages and agricultural problems, recognizing the human hand behind them

But, let’s go back to the last works of the vineyard.

Green pruning

The Roman agrarian authors tell of the various works that we include under the term “green pruning”, at the time called vites pampinari. For Varo, it is even more important than winter pruning and must only be done by expert people. Already Cato mentions the work of pinching off the suckers, binding the shoots and tearing off the leaves. Columella also adds the topping and thinning of the bunches, completing all the works of green pruning, as in our day.

They used the cultelli minores, small curved knives, to take off the suckers. The shoots of the vines were tied so that they would not be broken by the tools and animals during the passage, taking care to direct them upwards. These choices were made without knowing the physiology of the vines, as today. It was an empirical knowledge, born from the careful and rational observation of the response of plants to the different ways to done the works.

In August, Columella explains, the leaves are removed around the fruits in the territories where the climate is cooler and rainier, to avoid the bunches rot. Instead, he advises not to do it in hot places, like we do today. He also tells how vines were shaded with wattle matts in areas with a torrid climate, as his uncle Marcus did in Betica (southern Spain).

Soil tillage

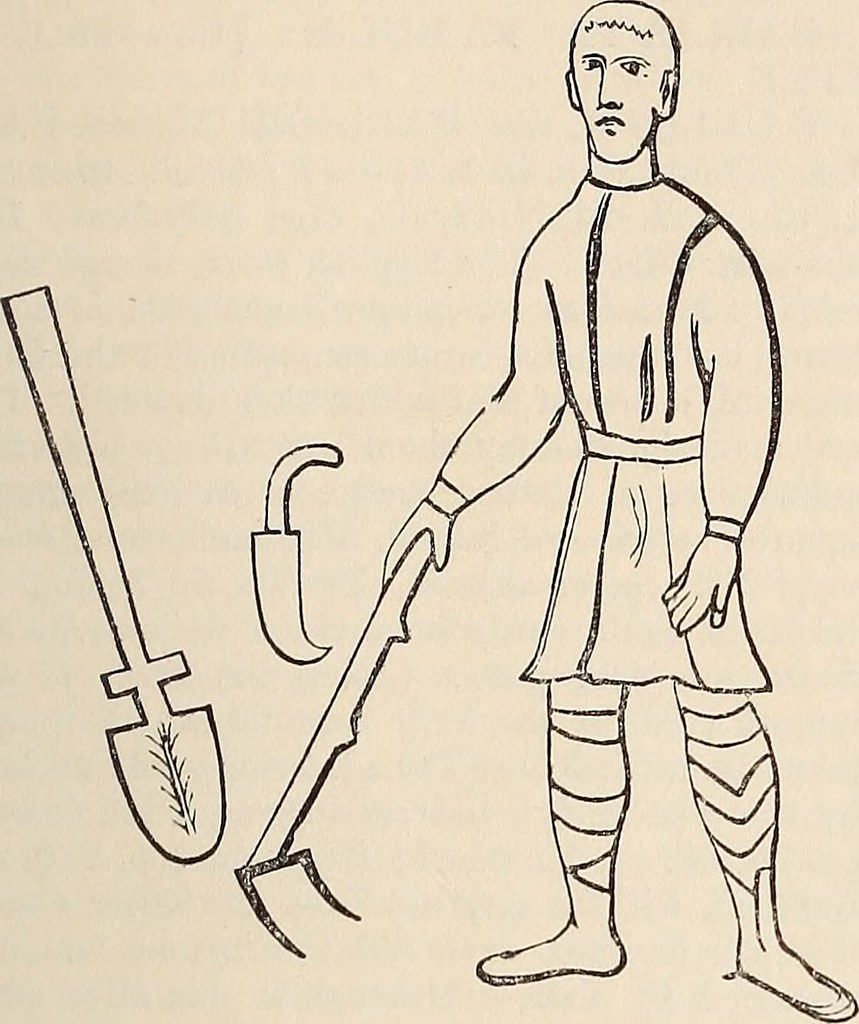

Soil tillage and weeding were also important then as today. The operation was called fossio and who did it fossor. Virgil uses the verb jactare.

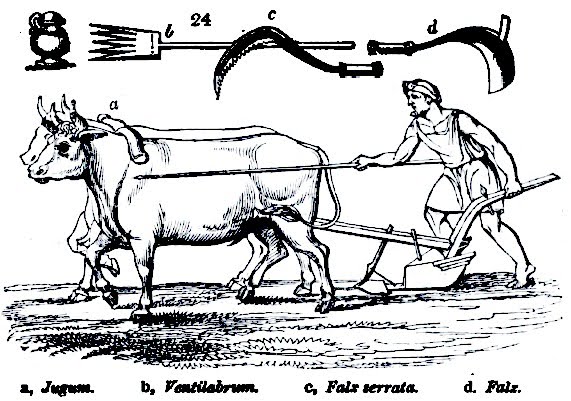

Where possible, it was always done with the plow pulled by oxen. Where it wasn’t impossible the use of the plow, they worked with the simple spade (pala or ligo) or with the bipalium (a spade with a transverse bar, which digs twice the depth of the common one). The marra was a large, toothed head hoe. The rastrum and the sarculum were different types of rakes. The irpex was a heavy rake pulled by oxen, like the modern harrows

The Latin authors recommend hoeing the vine at least three times a year: one when it sprouts, the other at flowering and the third for ripening. The vineyard with young vines must always be carefully dug to remove all weeds. These works are essential even today, even if done differently, to remove the vegetation close to the vine and to avoid unfavorable competitions in delicate moments of the life of the plant.

Another job was to dig out the soil under the vines (ablaqueare or circumfodere) with the dolabra or the dolabella, which were small axes. At the time of Palladius it was said excodicari: the earth was lightly dug around the vine and the most superficial roots were cut. Then, in the territories with a cooler climate, the bases of the vines were covered again with earth in the winter. This traditional work is no longer practiced today.

Grape harvest

The grape harvest was an event linked to religious practices, mainly dedicated to Jupiter, as already described here. The Vinalia Rustica festivities took place on August 19th and they served to propitiate the good weather during the ripening of the grapes. During the festivities, the grape harvesters could make jokes of all kinds, even offending passersby, without them may to react. Cicero speaks of the Auguratio Vineta, augural practices before the harvest. The official start to the harvest was given by the festivity called Auspicatio Vindemiae, with a ritual officiated by the Flamen Dialis, the high priest of Jupiter. He collected the first bunch in a public vineyard and offered it to the god, making an animal sacrifice. The ritual had to guarantee a good harvest. The period of the festivity varied every year, in relation to the harvest period. Pliny the Elder instead mentions a magical ritual used to ward off bad weather: they put a bunch of fake grape in the vineyard that should have attracted damage to himself, saving the rest.

Instead, Columella writes about the search for rational methods to decide the ideal moment of the harvest. He examines the systems proposed by various authors, such as the evaluation of the softness of the berry, the color and brightness of the fruit, the fall of the leaves. This latter is not surprising, because at the time it was frequent the late harvest. However, according to Columella, these are not good systems because they can also depend on other causes besides maturity, such as the bad weather or other. There are those who taste the grapes but even this method can be misleading for Columella, because he says that it is not always possible to understand by the tasting the relationship between sweetness and acidity of the grape, especially for the sourer varieties.

According to Columella, the best and error-free system is to evaluate the color of the grape seeds:

“The best thing, as I do, is to observe the natural maturation. Now, the natural maturity occurs if, after squeezing the grape seeds which hide in the berry, they are dark in color or black. In fact, only the natural maturity can give color to the grape seeds … “(De Re Rustica“).

In fact, the grape seeds are a good sign of the ripening of the grapes. At the moment of veraison (the moment of change of color of the berries), they change from green to yellowish or brownish, depending on the variety. Then, they become darker and darker. It is an objective parameter, good enough for the past. It has remained in use for centuries, although it is not very precise. In fact, it becomes increasingly difficult to evaluate the different shades of brown in the final stages. Today we evaluate a set of different parameters to decide the time of the grape harvest (see here). The grape seeds complete the information necessary, especially by tasting them on the maturation of the tannins.

Another recommended system in ancient times consisted in evaluating the growth of the size of the berries which, when ripe, stops. The suggested method is to remove a berry from a bunch and check it after some time. If the grape is not yet ripe, the other berries continue to grow and fill the void left by the removed one. When the berries no longer grow and the hole is not filled, the grape is ready. This system is also based on careful observation of what is happening in the vineyard. Like the previous one, it is a fairly good system but does not allow the precision that we are looking for now.

In any case, this knowledge, like that related to other vineyard works, had advanced for the time. Let us remember that, most likely, they were known and put into practice only by those who had the culture to read the agricultural treaties of the time. Certainly, most of the winemakers collected the grapes without knowing these techniques and without great precision for maturity, as happened in the vast majority of the vineyards until not long ago.

Often, in the past, much winegrowers collected the grape in the same period every year, when the neighbor started, when there was time from other works, … In ancient times, people also went to ask it to fortune tellers. In fact, Cato and Columella, in their texts, scold the winemakers who rely on astrologers, haruspices or other similar sources to decide the time of the harvest, instead of learning their craft!

When did they harvest?

Columella offers us the most precise testimony on the dates of the harvest, in his calendar of agricultural works (book XI of De re rustica). Columella wrote it in the second half of the first century. A.D., so in the Roman Optimum climate period. The harvest period seems very similar to ours.

In the monthly calendar of works, Columella begins to talk about the grape harvest in August, when he says that grapes are being harvested in lands with remarkably hot climates, such as Betica, in southern Spain (that of his Uncle Marcus) and north Africa. At the beginning of September, he writes, harvest begin in Italy in places near the sea and warm ones in general. In the second half of the month, he says that harvest is done in the great part of the vineyards. Finally, in October the harvest starts in the cooler areas. I remember that in the times of Columella the Julian Calendar was followed, we the Gregorian one, but more or less the months coincide.

The collection was done with small curved sickles, called falcula vindimiatoria. To reach the bunches of the vines trained to the trees, they used stairs. Pliny recommends to not harvest hot grapes or covered with dew, excellent advice also for today. The bunches were placed in baskets, as showed in many Roman mosaics or frescoes, or in wooden containers, as Cato writes.

How much did a vineyard of ancient Rome produce?

“Vinea est prima, si vinum multum siet”

Cato wrote in the second century B.C.: “The vineyard is the most convenient of the crops, if it produces a lot of wine”.

In fact, in general, compared to our parameters, the production told by the Latin authors is really high, as we have already seen in preview with the wonderful vineyard of Palaemon (here).

During the Roman time, as in all past eras even closer to us, the value of the vineyard was linked to a high productivity, even if they recognized an appropriate reduction in yields for wines of great value. With the exception of this small part, the large mass of grapes was used to produce large quantities of cheap wine. The various ancient authors provide us with some estimates.

In Cispadania (currently Emilia Romagna and also part of the Marche) it seems that an average of around 10 cullei* of wine was produced per jugero* (about 200 hl/per hectare), with extreme peaks of 15 cullei (about 320 hl/ha). A lower yield is witnessed for central Italy. Do you remember the wonderful vineyard of Palaemon which, according to Suetonius, produced 360 bunches for each vine? Columella also mentions it, after it had passed under the ownership of Seneca, with a production of 8 culei per jugero (about 170 hl/ha). Columella states that it was better to stop using a vineyard if it had fallen below 3 cullei per jugero (about 65 hl/ha). Of course, the few precious vineyards were excluded from this consideration, for which the mentioned minimum is of 1 culleo/jugero (about 21 hl/ha).

Consider that today the average yield in Italy is around 100-120 quintals/hectare (108 quintals/hectare in 2019), which correspond to around 75-90 hl/ha. In Tuscany, where the average quality is very high, in 2019 the average yield was 66 quintals/ha, i.e. just over 50 hl/ha. (these data came from the very useful blog “I numeri del Vino“, here)

Therefore, the Roman yields are enormous compared to ours, considering also that at the time the vineyards did not have the density of today. On the contrary, they were often in promiscuous cultivation. Thus, each single vine produced exaggerated quantities of grapes. We should also remember that the most common form of cultivation was the “married” vine (trained to a tree), which is very expanded form and leads to high production.

Some scholars have justified these numbers by thinking they were the maximum possible yields. There are those who argue that they should not be taken literally. There is the suspicion that some Roman authors may use a certain emphasis when they want to praise something. Certainly, the quantity, for mass production, was not lacking at that times.

We stop here for now, on the threshold of the cellar, with a grape basket on our shoulder. We will enter another time.

[alert style=”warning”]*Units of measurement mentioned in this article:

The used unit of the capacity for the wine production was the culleus, which corresponded to a large wineskin of about 520 liters, the largest Roman volume unit. Below it, there was the amphora which corresponded to about 26 liters. It took 20 amphorae to make 1 culleus. The basic unit of measurement was the sextarius, which corresponds to just over half a liter (about 540 ml). 1 amphora = 48 sextarii.

The most used unit for agricultural areas was the jugerum, about 2553 m2, more or less ¼ hectare (which, I remember, is 10,000 m2). The basic unit was the actus quadratus, half of the jugerum.[/alert]

Bibliography:

“L’agricoltura di Lucio Giunio Moderato Columella” volgarizzata da Benedetto del Bene, con annotazioni adattate alla moderna agricoltura e con cenni sugli studi agrari d’Italia del cav. Ignazio Cantù, Milano, dalla Tipografia di Giovanni Silvestri, 1850.

“Interventi di bonifica agraria nell’Italia romana”, a cura di Lorenzo Quilici e Stefania Quilici Gigli, ed. L’Erma di Bretchneider, 1995.

“Il vino nel «Corpus iuris» e nei glossatori”, Cornelia Cogrossi, (2003) In: La civiltà del vino. Fonti, temi e produzioni vitivinicole dal Medioevo al Novecento. Atti del convegno (Monticelli Brusati, Antica Fratta, 5-6 ottobre 2001). Centro culturale artistico di Franciacorta e del Sebino, Brescia, pp. 499-531.

“Interventi di bonifica agraria nell’Italia romana”, a cura d Lorenzo Quilici e Stefania Quilici Gigli, ed. L’Erma di Bretchneider, 1995.

“Storia dell’agricoltura italiana: l’età antica. Italia Romana” a cura di Gaetano Forni e Arnaldo Marcone, Edizioni Polistampa, 2002

“Terra e produzione agraria in Italia nell’Evo Antico”, M. R. Caroselli.

“Meteo, clima e storia. Le variazioni climatiche del periodo Romano”. Marco Rossi, 2007.

“Studi sui Libri ad edictum di Pomponio”, Emanuele Solfi, 2002, ed. LEM

“Origini della viticoltura”, Attilio Scienza et al., Atti del Convegno, 2010.

“La viticoltura e l’enologia presso i Romani”, Luigi Manzi, 1883.

“Storia della vite e del vino in Italia”, Dalmasso e Marescalchi, 1931-1933-1937.

“Storia del paesaggio agrario italiano”, Emilio Sereni, 1961.

“Il vino nella storia”, Enrico Guagnini, 1981.

“Il vino, storia, tradizioni, cultura”, Hugh Johnson, 1991.

“Contadini perfetti e cittadini agricoltori nel pensiero antico”, Valerio Merlo, Alce Nero.