In the first part I told about the mutations of our territory in Roman times compared to the Etruscan one, but also about how culture and social base have not changed so much.

Let ‘us now know better the local villae and how the ancient era ended in our territory.

(Remember: in Latin, “villa” is the singular, “villae” the plural).

The peculiarities of the “Bolgheri villa“

Many villae were born in the ager Volaterranus (the countryside of Volterra). They were the big farms of the time, that produced above all wine, olive oil and wheat. Only in the area closest to us, as many as 19 were found, born between the II century BC and the first half of the first century AC. They survived almost until the end of the ancient era.

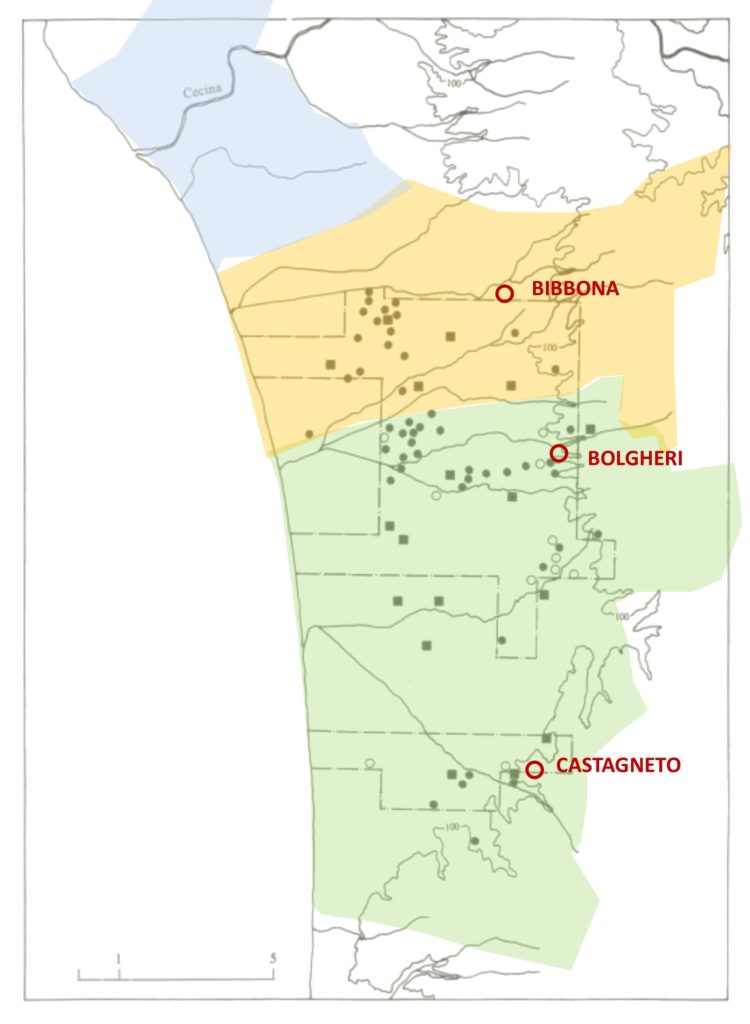

As can be seen from the map (the villae are represented by little squares), they developed mainly in the intermediate flat areas, far from the marshy coast, (more or less) along the line of what was to be the ancient Aurelian Way. Other villae are in the highest plain and on the first hills (on the right in the map). They are the same areas as today’s farms and wineries. However, let’s not take it for granted: between the prosperous Roman era and the actual situation there have been many centuries in which the territory was decidedly different.

The more classical Roman villae in the center or south of Italy, overall those in Campania (properties of the patrician families of Rome) were very rich and profitable farms. They were very specialized and based on slave’s work. They also had a relatively short life. They became larger and larger estates, with the concentration of Rome’s wealth in fewer and fewer hands. However, the enlargement made less convenient to invest in specialized agriculture. They were also thrown into crisis by the competition of extra-Italian colonies: they did not hold at the lowest price of wheat, olive oil and wine from Africa, Spain and Gaul. Many of these farms disappeared by the end of the second century AD. Others were converted in an extensive production of wheat or, above all, to grazing and breeding, with the degradation of the agricultural landscape.

The villae of our area instead were not very specialized, economically more modest, but much more durable. They have in fact survived for a very long time, generally up to the IV-V century AD, in one case even up to the VI. It was probably their local economy that made them longer-lived, less subject to external competition.

The remains of the local villae occupy surfaces ranging from 2.000 to 10.000 square meters. We do not know the dimension of their agricultural lands. I remember that the villa building included several parts, more or less large, with different names according to their function. The villa urbana was not in the city, but it was the master’s house part; the villa rustica instead included the part with workers’ quarters, stables and tool deposit. The part called fructuaria comprised the warehouses of agricultural products, the cellars, the granaries and the barns.

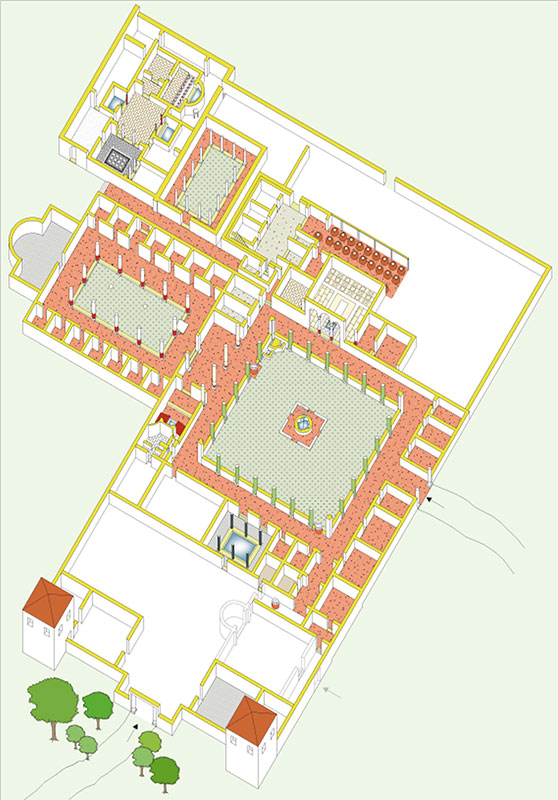

Unfortunately, there is little or nothing left of the numerous villae nearly Bolgheri. Not so far, the San Vincenzino Villa is one of the few preserved, which has been the subject of excavations and in-depth studies. It is located at north of Bolgheri, near the mouth of the Cecina river (today Marina di Cecina). It was owned by the already mentioned Caecinae family. Here there is the reconstruction of its planimetry. In the upper part of it you can also see the cellar, with the buried dolii (the wine-making amphoras). Below is there are a 3D reconstruction and a video that allows you to explore it.

The remains of the villae of the ager Volaterraneus include building material (bricks, roof tiles, stones, etc.), dolii and amphoras of different types. Unlike the villae of other areas, which over time also became refined dwellings (for the villa urbana), here it is rare to find luxurious decorative parts. Perhaps they were less used as residences, more dedicated to strictly agricultural purposes.

The decoration was found only in very few cases, which occurred however in much later times than elsewhere, only from the second century AD (in other parts this evolution took place already from the end of the I century BC). An important example of embellishment is the Castagneto Carducci Mosaic Villa (see box). Even the San Vincenzino Villa was added of rich decorations only from the end of the second century and, in several phases, up to the fifth. Perhaps there was a late discovery of the pleasures of country life, rather than a disaffection for that of the city. Perhaps it is no coincidence that this new course corresponds to the historical period of the decadence of Volterra.

[three_fifth][info_box title=”The Mosaic Villa of Castagneto Carducci” image=” animate=””]

At the foot of our Segalari hill, a little further towards Castagneto, the part of a sumptuous two-story Roman villa was found in the mid-nineteenth century. It was called Mosaic Villa because of the well-preserved mosaic floors. It dates back to the Augustan age (I century AD), while the mosaics were the result of a subsequent restructuring, of the II century AD.

Given the mentality of the time of the discovery, the mosaics were detached and taken to the Guarnacci Museum of Volterra. The remains of the villa were abandoned and have now completely disappeared (perhaps the stones were used for constructive purposes, as probably for the remains of many other local villae). The mosaics can still be seen today in the rooms of the first floor of the museum, even if their history and provenance are not told. At least, however, they were saved.[/info_box][/three_fifth]

Several of the particular characteristics so far listed of the villae of the ager Volaterranus (the scarce economic propensity, the owners of Etruscan descent, the lack of a typical Roman style villa life, the particular relationship with the people of the villages and small settlements, etc. ) have made archaeologists think that, at least in the first centuries, these estates had a different meaning compared to the Roman mentality.

In Roman culture the villa was born as an economic investment devoted to intensive agriculture, as Cato tells in the II century AC. Varo tells us, about 120 years later, that the villa then evolved as a place of intellectual leisure and relaxation for the owners, a refuge from the social and political tensions of city life.

For the local domini (lords), with a Romanized name but perhaps still very tied to the culture of their ancestors, the villa seems at first represent a new prestigious symbol of power and control of the territory, as the great burial mounds of their Etruscan forefathers. The cultural Romanization will be only centuries later.

The local wine trade.

Although they were not very rich and luxurious villae, they produced agricultural products that represented an excellent economic resource for the territory: above all wine, olive oil and cereals. Partly they were consumed locally and partly exported, thanks to good road system (the Aurelian Way) and various ports. They arrived in Volterra mainly by ship, along the Cecina river. For Rome and other destinations, they left from the Vada port and from other smaller ports along the coast.

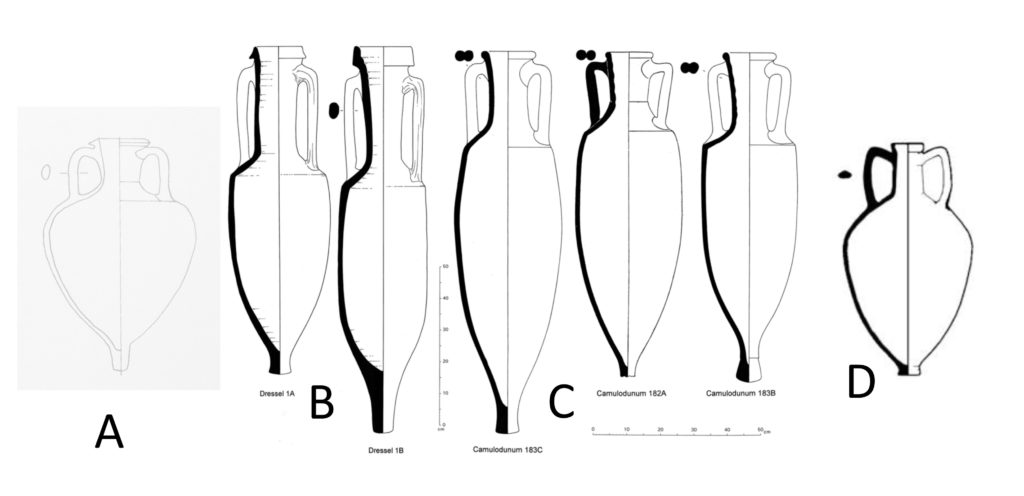

We are especially interested in wine. Its trade was traced thanks to the recognition of locally produced transport amphorae.

It appears that in the beginning the trade involved the northern area of Etruria. From the first century BC, it expanded: amphorae of wine from the Ager Volaterranus were found on the Ligurian coasts, in those of Mediterranean Gaul, along the river routes of the Rhone and the Rhine. From the III to the VI century AD, the trade returned to being mainly local, but with still finds of local wine amphorae in Rome and in Corsica.

The crisis and the disintegration of our territory.

Already in the third century, there was a general crisis of the Empire that did not however have great repercussions in our territory. Small farms (in fact, several disappeared) suffered the most, minus the villae and the villages that showed mining activities. The real crisis (throughout the Western Roman Empire) began between the fourth and fifth centuries AC, with increasingly important economic and political difficulties.

The degradation of the territory spread more and more also due to a progressive depopulation, due to the beginning of barbarian incursions. The first were conducted by the Visigoths (410-412), then by the Vandals. Then the Greek-Gothic war followed, with its destruction, famine and pestilence, ending with the Lombard invasion (end of the 6th century).

The abandonment of the territory led to the gradual came back of coastal wetlands, after millennia of reclamation and care. The swamps will remain for many centuries to come.

The human settlements progressively diminished and the few remaining moved more and more towards the hilly hinterland. On the one hand, the populations escaped the spread of coastal marshes. On the other, they moved away from the Via Aurelia which had now become the gateway to the territory of the raiders.

The Aurelian Way had already been degraded for some time. In the Late Empire many sections of the Roman roads were now impassable, without any maintenance on the part of increasingly weaker administrations. The (aforementioned) Namantianus, at the beginning of the fifth century, tells that he had had to face the journey to Gaul by ship precisely because of the terrible conditions of the Aurelian Way: “I chose the sea because the roads are, in the plains, flooded with rivers and in the hills full of stones. Since the ager Tuscus (the Tuscan countryside) and the Aurelian Way have been taken by storm by the Goths, there is no longer a farm to control the forest, there is no longer a bridge that crosses a river, it is better to rely on my sails and take the road of the sea”.

The viability on the lowland was gradually replaced by new inland routes, halfway up the hills or on the ridge, far from the unhealthy air of the marshes, also following the displacement of human settlements. Thus, a new more disorganized road system was born, which responded above all to local needs. This will also be reflected in the birth of the new medieval abbeys, villages and castles, which will take place only in the hill areas. But we will talk later about the Middle Ages.

The viability on the lowland was gradually replaced by new inland routes, halfway up the hills or on the ridge, far from the unhealthy air of the marshes, also following the displacement of human settlements. Thus, a new more disorganized road system was born, which responded above all to local needs. This will also be reflected in the birth of the new medieval abbeys, villages and castles, which will take place only in the hill areas. But we will talk later about the Middle Ages.

The glorious ancient era ended on a territory now almost depopulated and devastated.

In the next posts we will try to better understand how the wines of this era were and how they were produced.

Bibliography:

-“Storia del paesaggio agrario italiano”, Emilio Sereni (1961)

-“Analisi di Agricoltura – la viticoltura e l’enologia presso i Romani”, Luigi Manzi, 1883, Roma tipografia Eredi Botta.

-“Castello di Donoratico. I risultati delle prime campagne di scavo (2000-2002)” A cura di Giovanna Bianchi, Quaderni dell’università degli Studi di Siena.

-“Populonia e la romanizzazione dell’Etruria Settentrionale”, Franco Cambi et al., Atti del Convegno Internazionale Sapienza Università di Roma, 7-9 maggio 2012, 2013.

-“Le stele funerarie d’età imperiale dell’Etruria settentrionale”, di Giulio Ciampoltrini, in Prospettiva, 30, 1982, pp. 2-11 “Ricognizioni archeologiche nel territorio di Volterra: la pianura costiera” di Alessandra Saggin and Nicola Terrenato, Archeologia Classica, Vol. 46 (1994), pp. 465-482 (18 pages), Published by: L’Erma di Bretschneider

-“Sepolture tardoantiche in Toscana (III – VI d.C.): i corredi e le epigrafi”, di A. Costantini, Published in “Studi Classici e Orientali”, 60, 2014, pp. 99-161

-Il Museo Archeologico di Rosignano Marittimo – “Risorse e insediamenti nell’Etruria settentrionale Costiera” – Ministero per i Beni e le Attività Culturali – Polo Museale della Toscana, Soprintendenza Archeologia Belle Arti e Paesaggio per le province di Pisa e Livorno, Comune di Rosignano Marittimo, Museo Civico Archeologico Palazzo Bombardieri Pubblicazioni varie del Museo Archeologico del Territorio di Populonia e dei Parchi della Val di Cornia.

-“Il paesaggio come risorsa – Castagneto negli ultimi due secoli”, Mauro Agnoletti, 2009, Ed. ETS.

https://www.museoarcheologicocecina.it/il-museo-archeologico/la-villa-romana-di-san-vincenzino/