What are we doing now in the vineyard: the topping

After the fruit set, this is the moment of the topping, that is, the cutting of the final parts of the growing shoots, the apex and the last leaves. It is an ancient traditional practice, recommended since the Roman agronomist Columella. Today we know why. It is not a generalized practice, but it brings several advantages that I am now trying to explain to you.

The topping is part of the large family of works called "green pruning", which modify the canopy of the plant. If done properly, they improve the production and the sustainability of the vineyard.

These practices are in general usefull to keep the canopy within certain growth limits, to avoid the risk of accidental breakage of the branches. They also serve to regulate the balance between vegetation and production. It is important that the vine has sufficient canopy, in relation to its environmental and production conditions, to accumulate sufficient energy in the form of sugars. However, it is not only a question of quantity: the sugars correct distribution between the various parts of the plant is also fundamental for an optimal ripening. Some practices of green pruning also affect these energy balances. However, the canopy must not even be too much big, for an optimal exposure at the sun of the leaves and the bunches (these, depending on the climatic conditions, sometimes is better a more exposure, sometimes they must more protected). Finally, the too overlapping vegetation creates unfavorable, humid micro-environments that favor different diseases. So certain green pruning jobs also serve to prevent pathogen infections.

Let's go into detail: why do we do the topping?

The most simple reason is to cut the very long vine shoots. The physiological implications are instead listed here, in a synthetic way:

- The topping makes the vines more resistant to water stress: the apical leaves are the largest consumers of water. By removing them, the plant achieves a better balance for the available water resources.

- It contributes to the creation of more balanced wines: the cutting of the apices blocks the development in height and stimulates the lateral buds, which form the lateral shoots. This shifts the internal balance, lowers the general vigor and therefore leads to a slight decrease in the production of sugars, which, at the same time, are better conveyed towards the bunches.

- It improves the micro-climate of the canopy: the cut slightly lightens the canopy, with greater illumination and aeration of the underlying leaves and bunches, improving the general quality. Furthermore, the humid environmental micro-conditions which favor various diseases are avoided.

- It rejuvenates the canopy: at first it actually ages it, because it cuts the tips with young leaves. Later, during the maturation, the stimulation of the lateral shoots leads to the birth of many new young leaves, very efficient in photosynthesis. The leaves of the main shoot begin to age at this stage. The overall rejuvenation helps to support an optimal maturation, allowing the accumulation in the bunches of all those components that will give the wine richness and complexity.

Be careful, however: all the viticulture practices are optimal if well done. They can create problems if done wrong .

The topping is optimal at this stage, immediately after the fruit set. If done too early it blocks the growth of the shoots and limits the canopy. If done too late, its action on the delicate physiological vine balance can become more negative than positive, because it can cause a too strong decrease in the sugar content and weight of the grape. For example, in cooler climates, the late growth of the lateral shoots goes to compete too much with the ripening berries for the absorption of the energy resources of the plant, to the detriment of the latter. In warmer environments, on the other hand, late topping does not particularly stimulate the growth of the lateral shoots. The risk is taking away leaves without benefits, only getting to decrease the canopy.

How much to cut? It depends on situation, but usually it is short. Generally, too drastic cuts must be avoided: we are not pruning an ornamental hedge! As said, if the leaves are too few, we risk negative consequences. It has been calculated that the bunches need to have a sufficient number of leaves above them for optimal ripening (at least a dozen). The leaves above the cluster are those that provide the sugars for ripening. Those below send their sugars essentially to the branches and perennial organs (trunk, roots). If the vegetative luxuriance is too intense that it requires very important cuts, we must consider changing something else in the general management of the vineyard.

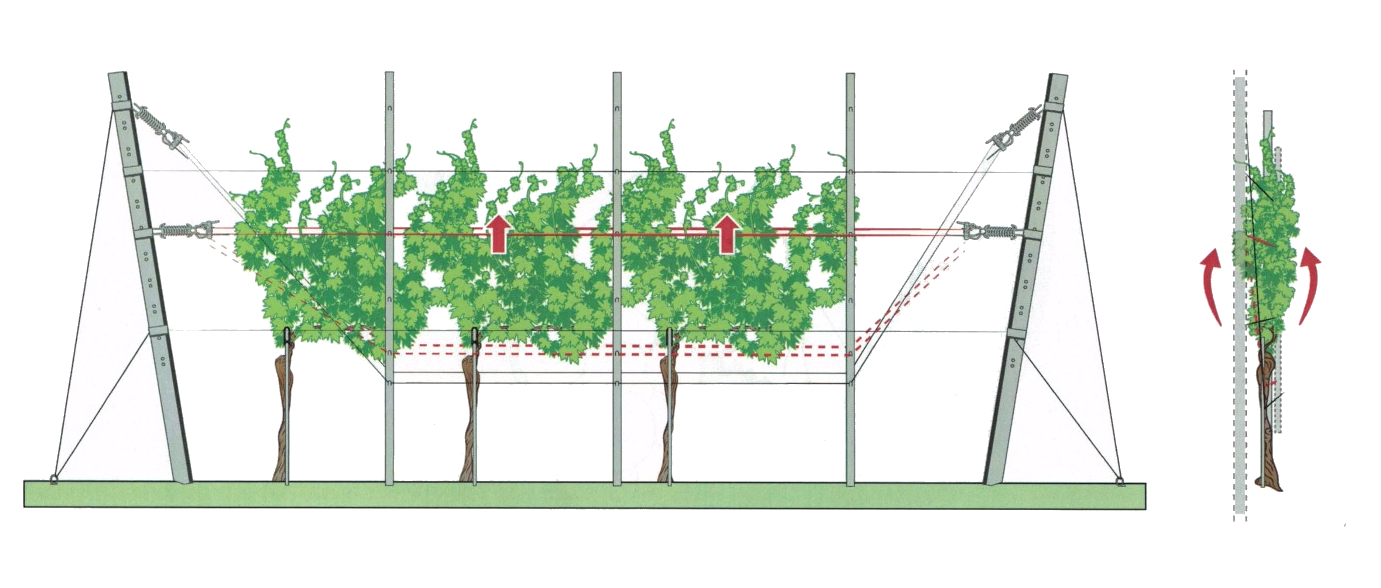

Although the attention I have explained is needed, topping is not a job that requires a great precision. For this reason, in a espalier system like ours, it can be done mechanically, also because it is very important to end it quickly, in the short time that follows the fruit set.

New vintage: Criseo Bolgheri Bianco (white) 2018

The wait was long but the new vintage of our Criseo Bolgheri DOC Bianco, 2018, has finally arrived.

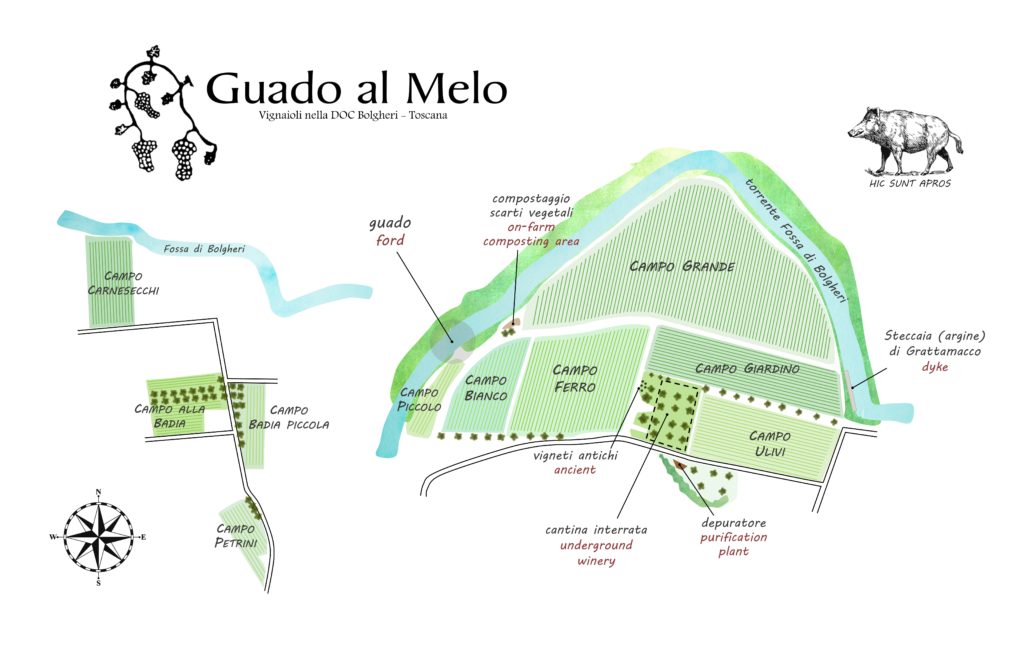

There is always a bit of a wait, but this year has been longer than usual. Every year we finish it before the following year is released because it is a wine produced in small quantities. In fact, it comes from a single vineyard of only 0.7 hectares, Campo Bianco, located close to our ford (= Guado), before the forest begins.

The 2017 vintage had been particularly low: the drought had significantly reduced the production yields. Because of this and the more attention derived from the TreBicchieri Award of the Gambero Rosso, the 2017 vintage finished very quickly. If you are curious to taste it, there are only a few last Magnums.

2018 was a very regular year, with characteristics of greater climatic freshness than 2017. Spring was very rainy and made it possible to recover the dryness of the previous year. Summer was instead, as normal, hot and dry, without particular excesses. Some short rains cooled the temperatures at the end of summer, without creating problems. This seasonal trend allowed a longer ripening than usual: we harvested the Campo Bianco vineyard on September 10th.

The harvest date varies with the vintages: in the hottest and driest it can be brought forward to the end of August or in the first days of September, in the cooler it can moved a little further. The important thing is to seize the perfect moment of synergic maturation of the vineyard, in which the perfect balance is found between the varieties present (mainly Vermentino, Fiano, Verdicchio, Manzoni Bianco, Petit Manseng). In this choice, the experience we have acquired in over twenty years is very important.

This wine is a field-blend. The grapes, which grew together in the Campo Bianco vineyard and were harvested together, are also co-fermented after the selection. The co-fermentation is a old traditional practice, capable of making them express a unique personality.

Its taste? It is full-bodied, soft but balanced by a great freshness. It also has an incredible aromatic complexity, with aromas that change constantly as the wine is oxygenated in the glass. Fragrances of grapefruit, tropical fruit, pastry, sage, white flowers, saffron, mineral notes, hydrocarbons are released. Over time the latter will prevail, because it is a white wine that can have a long aging, thanks to the fact that after fermentation has remained in steel on the lees for almost a year. Now, we propose it after another year in the bottle.

It is excellent now, but if you love whites with more evolved notes, such as Michele and me, you can safely keep it in the cellar (at low temperature and with a bottle lying down) for a few more months ... or a few years.

If you resist!

We are waiting for you

Our winery is open now, with special opening hours. The wine shop is open:

from Monday to Thursday 10.00-12.30 15.00-17.30

Friday 10.00-12.30 15.00-17.30

Saturday 10.00-13.00 15.00-18.00

Guided tours and tastings are by reservation only. Please, phone at 0039 0565 763238 or send a message to info@guadoalmelo.it

Spring in the vineyard: the works of this period

In this season the growth of the vine is very fast. There are so many jobs to do!

We are now finishing the green pruning works, that is, a set of different interventions that act on the green parts of the plant (leaves, shoots, branches, bunches), so called in contrast to the "dry" or winter one (which we did on the branches). We do these jobs all by hand, because we must carefully chosen how to do them for each individual vine. Let's see those of this period.

Desuckering is the elimination of shoots that arise from the rootstock of the vine, as well as those that arise from the latent buds, on the trunk or other woody branches. It is important to do this very early, before they develop too much. We also has done the thinning of the shoots on the canes of the year.

https://youtu.be/nNVu7MpobYk

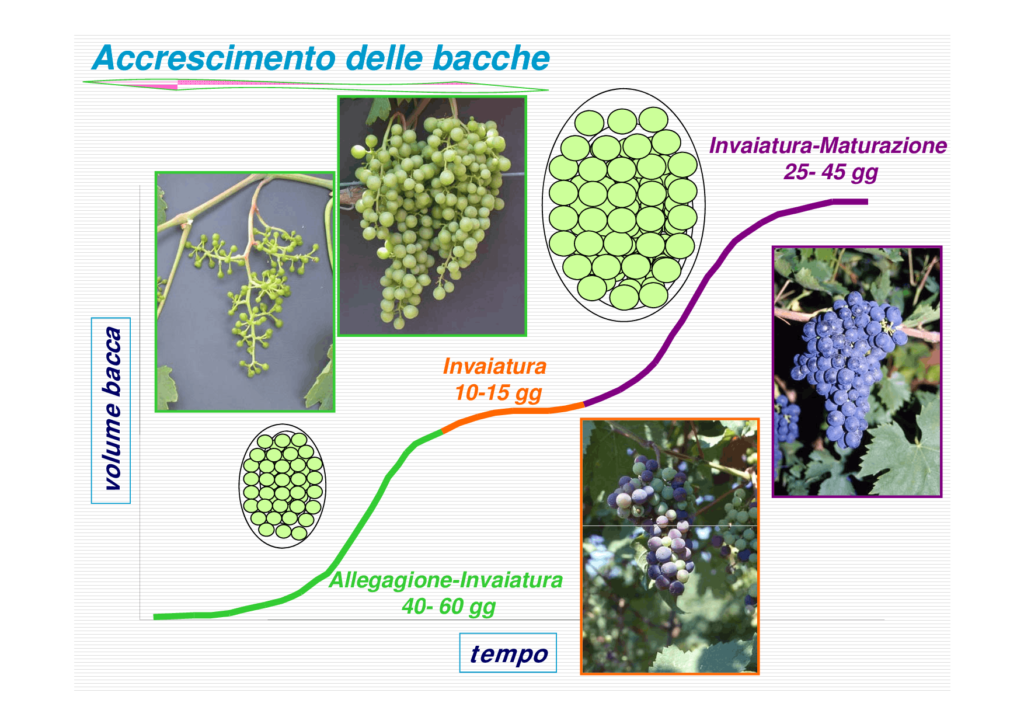

All these green pruning jobs are very important to help the vine find the right balance. They allow to decrease the load of the plant, so that future bunches ripen as well as possible. They prepare also the future winter pruning, which will be easier. Furthermore, the leaf mass is made less dense, thus avoiding the creation of an humidity environment conducive to the development of mold or other diseases. Finally, they also prevent blossom dropping problems. In general, compared to the flowers produced by each vine, only 20-50% (depending on the variety) will be fertilized and will set, that is, it will form the fruit. There is a problem when the blossom dropping is higher than normal for the variety. It can depend on physiological imbalances, difficult climatic conditions, nutritional deficiencies, various diseases (virosis, downy mildew, powdery mildew, vine moth, ...).

The work we are doing now is the arrangement of the branches in a vertical position. In espalier systems like ours, this is done by lifting a pair of parallel wires. The effects are numerous: the branches do not invade the inter-row and we do not risk breaking them in the passageways with the tractor, they are better distributed and less bundled. The vertical position, as I already explained in the post on pruning, increases the physiological activity of the shoots.

In this period it is also very important to understand, as soon as possible, if there are nutritional deficiencies in the vine. However, a dedicated post will be needed on this complex argument.

Depending on the environmental conditions, we must also take action to avoid the problems caused by powdery mildew and downy mildew, according to the principles of integrated pest management (sustainable viticulture practices). In this spring 2020, at least for now, we are more at risk of powdery mildew than downy mildew, as is usual for the climatic conditions of our territory. Downy mildew is a problem in the most humid and rainy areas. As for the vine moth, we have already distributed traps and systems of sexual confusion (biological control) in the vineyard.

Make every day Earth Day

Today is Earth Day but we must remember it every day, with actions than with words. We, as winegrowers, know that if our work is not sustainable, it cannot have a future.

For this reason, we choose every day the current best practices of integrated sustainable viticulture, which garantee 0 residues in wine and the environment, as well as a rich biodiversity in the vineyard.

For this we have built an underground cellar, which "disappears" in the landscape, which allows us to save 70% of energy, with a rainwater recycling system that reduces consumption by 40% (for all internal uses for which no drinking water needed).

For this reason, in the cellar we work with craftsmanship, respectful of the grapes and the exaltation of our most precious heritage: our territory.

More info on our website www.guadoalmelo.it

Renewal of our vine and wine museum

This suspended time is ideal for arranging the winery, to be even more beautiful and welcoming for when you can come back to us. These signs had broken by the wind. I took the opportunity to renew them.

Happy Easter

Dear friends, happy Easter to all!

We wish you the best, even if at this moment it is really difficult to find words of hope, with so many deaths and suffering people, struggling economy, politicians who give us only empty words, …

Yet, Albert Camus wrote that hope (alone) equals resignation. And to live is not to resign oneself.

As you, in general we always show our happy and optimistic face, but our work is already made of thorns and roses.

We work with nature, that can fill us with satisfaction and joy, but sometimes it gives us terrible blows: the drought, the frost, a bad year, ... Furthermore, we have to fight with a suffocating bureaucracy, the importer that suddenly leaves us, the tractor or the bottling machine that breaks suddenly (a tad more than petty cash!), ...

That's why we are used, as you, to being strong against the life's obstacles, to reinventing ourselves, to work as much, as and more than before. This virus is one of the worst blows for all of us, but it doesn't scare us: if it not will take down us, it will make us even stronger.

So, we wish you to have strength. Let's stand strong, for us and for our loved ones, for the less fortunate, for those who cannot really make it alone.

Everything will be fine, but only if we work hard for it.

... and don't forget to drink an excellent wine, the best remedy for the spirit!

Annalisa and Michele Scienza

photo: Katrin Pfeifer

Rute, new vintage 2017

I had to write the data sheet of the new vintage of our Rute Bolgheri Rosso, 2017. I thought about what Bolgheri is for us: it is our home simply. So, I looked for what we (Michele, me and our children) mostly love of our living here, and I described it like this, in few lines:

"Bolgheri was a very difficult, harsh,

and waste land for centuries.

Today it is a Mediterranean garden,

with a still somewhat wild beauty.

For us, it is our home,

which has the scent of the hill paths

in the scrub, of the salty sea smell

in the sand dunes,

which has the sound of the waves of the sea,

of the cackles of the boys

who are bathing in the ford*, …

Rute is this Bolgheri, familiar to us,

that we look for in the earth and

in the stones of our vineyards,

in our craftsmanship."

What do you say?

*Guado al Melo means “ford* at the apple tree”. There is really a ford near our vineyards, where our children and their friends have played.

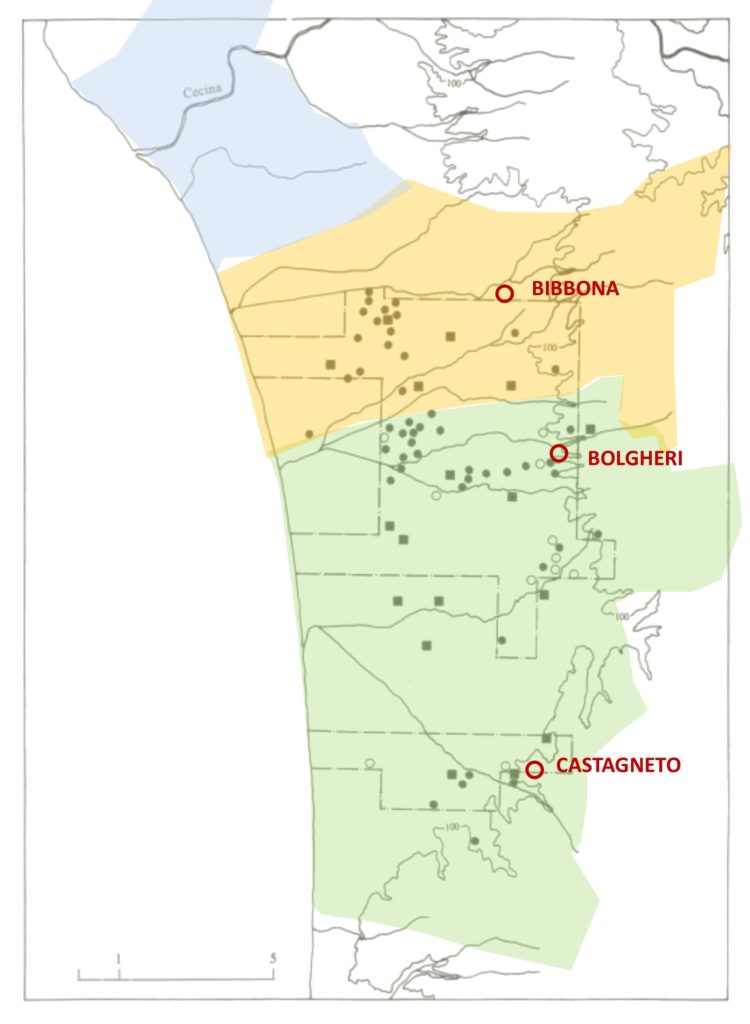

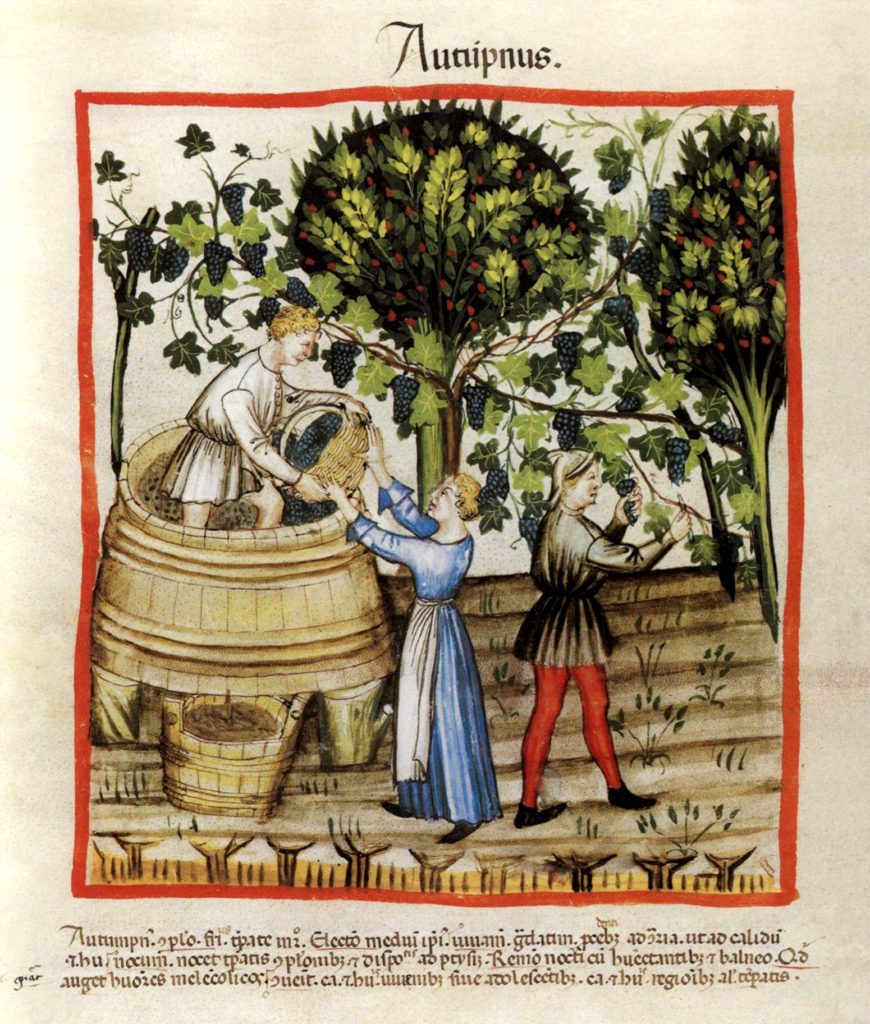

Viticulture in Rome and the rediscovery of the Genius Loci

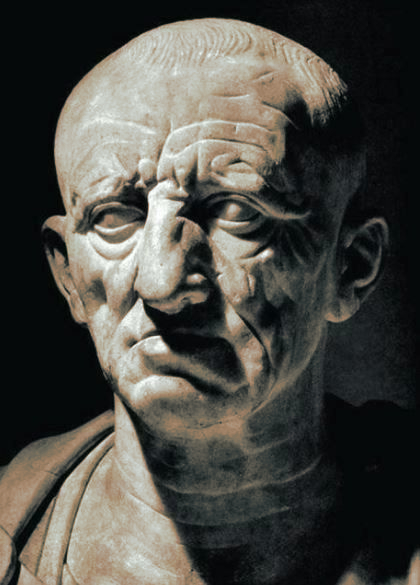

The Romans were great winegrowers. At the time of their agricultural acme, they had reached good empirical knowledge of the vineyard practices (with the due limits). Later, it will take centuries to recover these skills. Among these knowledge, the truly disruptive element of Roman viticulture, which will mark the Italian (and European in general) vine-wine culture up to the present day, was the understanding of the inseparable link between wine and territory.

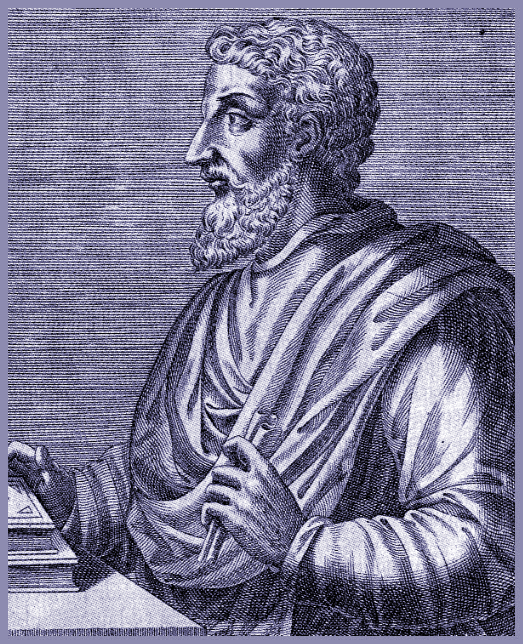

Roman viticulture knowledges were built in centuries, from a primitive viticulture of the origins to what is considered the apex, the second part of the first century BC. In this period Columella lived, who is considered the first agronomist in history. His work "De Re Rustica" is so precise and detailed that it is considered the first real agricultural treatise ever. The agrarian authors after him will essentially resume its contents and not for a short time: Columella will remain as the main reference for agriculture at least until the end of the eighteenth century.

[one_third][info_box title="The choice of soil, climate and varieties according to the ancient Romans" image="" animate=""]Let's see what the agrarian Latin authors wrote about wine and territory, especially Columella.

Columella writes numerous reflections on the choice of the place of the vineyard, in relation to the soil and climate, and the consequent choice of the most suitable varieties. Not all of his considerations are correct, in light of our knowledge, although many are so (albeit generic). What is relevant is that the Romans understood the importance of these relationships more than two thousand years ago.

Columella writes that the best soil should not be too clayey and not too light (today we would say medium-textured), but get closer to the latter. It must not be too poor and not too fertile, but better similar to the second. The steep terrain is not the better, not even the extreme plain. The better is a more or less inclined plane (to drain the water). It is necessary to investigate the type of land, even underground, and not only look at the surface. The best choice, however, is to experiment with the different types of soil, to understand the different production responses.

In general, however, if the soil is suitable for giving pleasant and precious wine, it is better to plant varieties that are not too productive, but not too little either. If, on the other hand, the soil is not so good, it is better to plant a very fertile variety, to have a good yield in quantity.

Nel piano si ha vino più in abbondanza, nelle colline quello più gradevole. Le vigne inclinate verso il nord sono più fertili, ma quelle verso il sud danno il vino dal gusto migliore. Nei luoghi freddi è meglio avere l’esposizione a sud, in quelli tiepidi è meglio l’est, purché in entrambi i casi non siano esposti a venti provenienti da quelle direzioni.

We know the names of many Roman varieties, in fact they have been listed in several ancient texts. It is really impossible to connect them to modern ones. The names changed even at that times. Varieties that are listed by Cato are no longer named by Columella and Pliny, who write 200 years later. Even these two authors, who are contemporary, sometimes list different names. Anyway, I don't write the varieties, also because they can be found everywhere. It seems to me more interesting the part where Columella explains the choice of vines in relation to the territories.

He writes that, when you have to make a vineyard, you must be personally informed about the best vines to plant and do not entrust the purchase of the cuttings (viviradicem) to others. Better still is the internal nursery (vitiarium). It must not be placed in a soil of worse quality than that of the vineyard.

The farmer must understand that the varieties of vines that resist fog are suitable for the plains, instead those that tolerate drought and winds are more suitable for the hill. So, in the fertile soil, the not very vigorous vine will be planted, in the poor soil the most vigorous vine, in the dense soil the strong vine that produces many canes. The vines that produce large and soft berries are not suitable in moist soil. Those with small and hard grapes are better. Different varieties can grow in well-drained soil.

The winegrower, however, must not only to pay attention to the soil but also to the climate. Where there is colder and fog, the early vines are better, the fruits of which ripen earlier or those that have robust and hard grapes. Where there is a lot of wind and storm, robust vines with hard berries will also be planted here. Where it is very hot, the most tender varieties and that have the most compact bunches are the best. In the most placid and serene places, you can put all sorts of vines, but the early season ones are the better.

The wise winemaker in addition to the best vines, should always plant different varieties, because each can respond differently to the adversities of each vintage.

From Columella description, we can also understand that the common practice at the time was the field-blend vineyard, i.e. with multiple varieties mixed together, as remained in Italy (and other European territories) for centuries to come. According to Columella, however, it is better to arrange the varieties separately. He lists the advantages of this choice. Not all of them bloom and mature at the same time. It is not easy to collect together grapes with different maturity: if you wait for the later grapes, the first ones are eaten by birds and damaged by winds and rains. The separation also allows the vintner to know how to prune each of them, because at that time there isn't the leaves to make the typology understand. In addition, the winegrowers can choose to plant each species in the part of the vineyard best suited to its characteristics, for the soil or with the right exposure. However, Columella admits that it is often difficult to implement this principle, also because most of the winegrowers cannot distinguish the different varieties. However, if not possible otherwise, Columella writes that at the least it is better to plant together those varieties that have similar taste and similar maturity. We can find identical considerations to Columella's ones in numerous texts of the agronomists of the nineteenth century. As Columella, also they tried to ferry the viticulture of their times towards more rational forms!

The vineyard with more varieties is called by Plinius vitis conseminea, conseminales vinea by Columella.

[/info_box][/one_third]

In his and in other Latin texts, it is underlined and examined how each soil and climate require the choice of the most suitable grape varieties, the different choices of work approach and the production of different types of wine. This, linked to the fact that the Romans first identified wine with the place of origin and the year of production, makes us understand that they were the first to conceive that fundamental concept that we commonly call today "terroir".

The Romans had not given a name for this concept, just as it will not be done long in Italy and in the rest of Europe. Yet, it has been a tradition for millennia.

This concept was examined in depth in more recent times, within that long process of transformation of the twentieth century wine sector, that is the basis of the birth of modern wine. In particular, this argument was mostly discussed after the Second World War.

In this period many scholars and experts began to reflect deeply on the concept of wine and territory, as a basic element of wine European culture.

Its definition is not simple, as it is made up of many factors. The first, the most obvious one, is certainly the territorial one in the strict sense, linked to the geographical characteristic, therefore soil and climate. In relation to these pedo-climatic differences, there are also the different answers that each grape variety can give in a different territory or micro-territory. Furthermore, the annual variations of these elements, linked to the vintage, must be considered. However, not only the "natural" elements intervene. A territory is also linked to the local traditions, their transformations over time, the transformation of the landscape by the man, the history, the local wine culture, the production choices, etc.

The scholars understood necessary to find a name to express this so complex concept. The word "territory" is limiting, too common, and therefore possible cause of misunderstanding. The easiest mistake, which many persons still make today, is to reduce it to the pedo-climatic characteristics only. Thus, two terms were born: Genius Loci and terroir.

They are different? No, they express more or less the same concept, but they are born in two different cultural spheres.

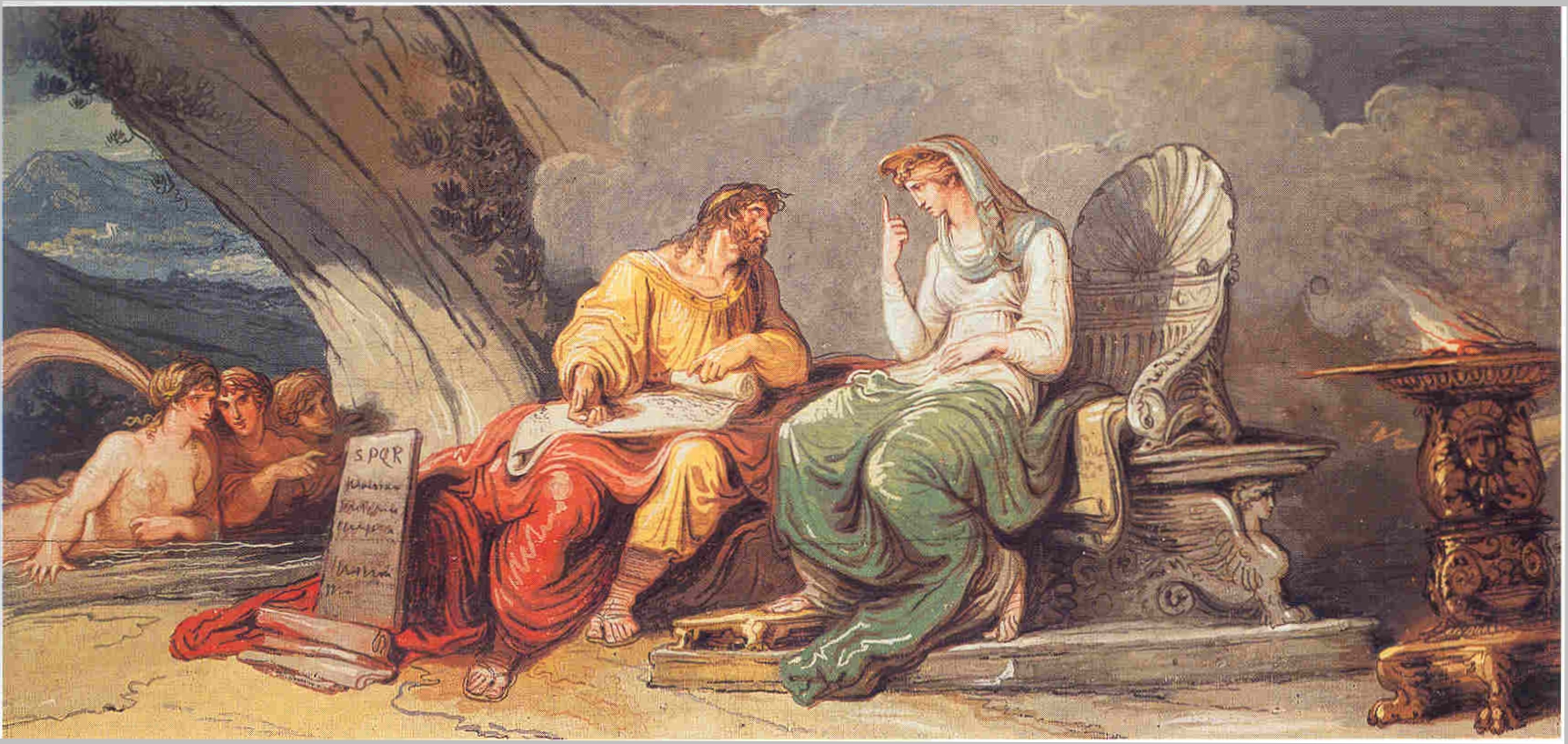

The Genius Loci

In modern times, the Latin locution Genius Loci was first introduced in architecture, inserted in the historical reflection on the concept of place. From here it was transferred to the concept of wine territory.

What does mean Genius Loci?

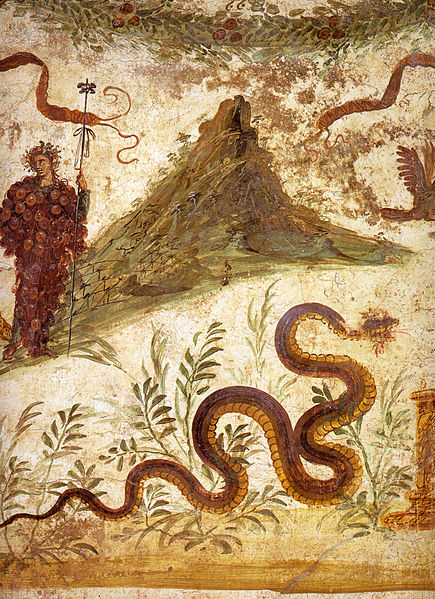

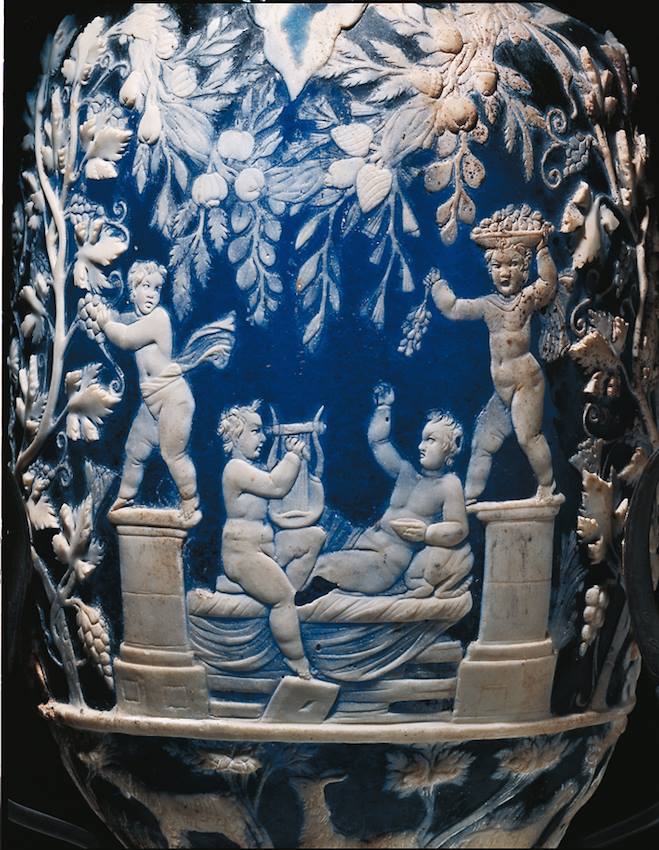

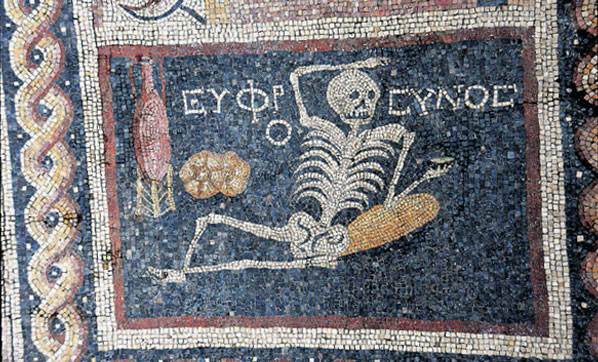

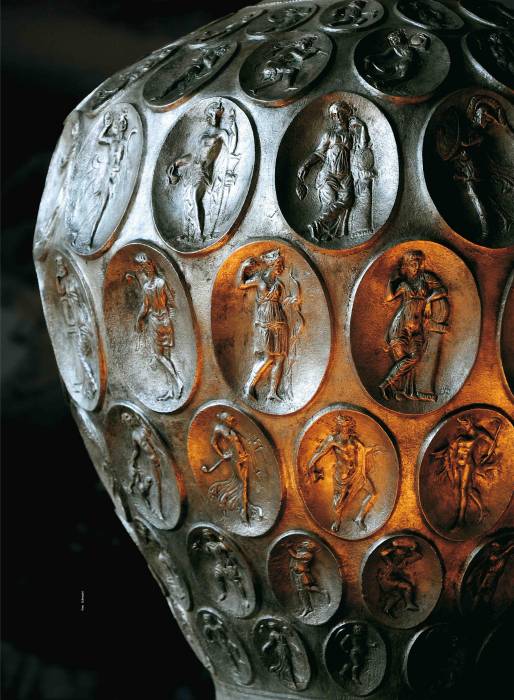

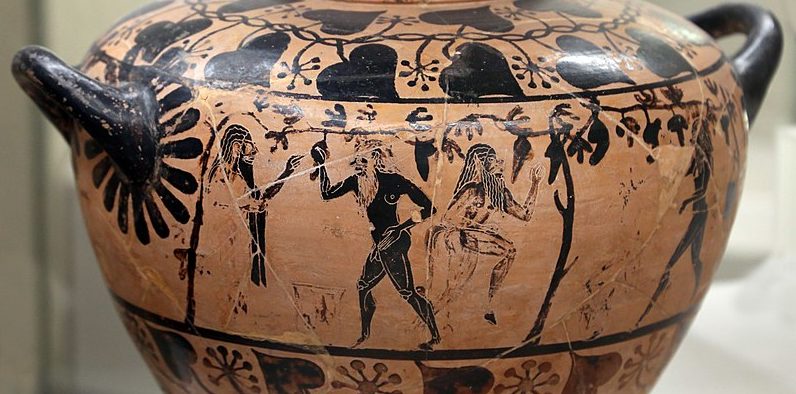

In ancient Roman times, the Genius (from the verb gignere = to create, to generate), was a tutelary spirit, a benevolent god who watched over every person. More or less, the same concept was present in Greek culture, where it was called daimon. It was not only proper of the individual, but also of the community: there were also a Genius of the family, of the Province, of the State, of various associations, etc. The concept was also extended to places, with the name Genius Loci, the genius of the place (locus). It was a benevolent caretaker who watches over it and the people who lived there or even a sort of personification of the place. According to Servius:

"nullus locus sine Genio est" (no place is without a genius).

Virgil, in the Aeneid, describes it (him or her, the Genius may be masculine or feminine) as a big and slimy snake that crawls out of the depths of the earth (book V, 84-75). It was often depicted as a snake, an animal considered a symbol of luck. Its image on the walls of a building was the expression of the desire to put it under the protection of the Genius Loci. Often it is depicted as a snake wrapping himself around an altar, where it goes up to devour the offerings that people have been made to him.

To have its benevolence, it is necessary to respect its place, to invoke its protection and to offer it perfumes, flowers, fruits, focaccias and wine. Then, the Genius would have been benevolent, it would have revealed himself/herself filling the place with sacredness and lucky. On the other hand, if the person had been hostile to the place, devastating it or exhausting its resources, then the genius would have been antagonized. It would have denied itself, it would have emptied the place of its presence, thus causing misfortune.

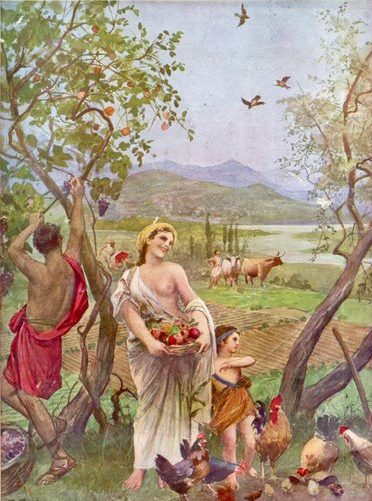

Sometimes, the Genius is represented as a human figure, surrounded by symbols of plants and animals typical of the place. The more common picture of the Genius was a winged person, from which the depictions of the Christian angels are derived.

These beliefs will however be assimilated into Christianity in the figures of the Guardian Angels and Patron Saints.

The architects Aldo Rossi, in the late 1960s and, above all, the Norwegian Christian Norberg-Schulz, a decade later, were the first to introduce the figure of the Genius Loci in the modern debate on the meaning of "place". The Latin locution Genius Loci thus began to be used to define the complex multiplicity of those elements that constitute the deepest identity of a place. They include all its intrinsic characteristics, made up of geographical and structural, natural and artificial elements, but also by immaterial and changeable elements, such as historical and cultural stratifications, the very way in which the observer perceives it, its character, the colors, the variations of the light, etc.

Few years later, prof. Attilio Scienza, taking inspiration from the architectural debate, proposed the use of the figure Genius Loci in the wine sector, to powerfully recall that link between wine, territory and culture, inherited from the Romans.

The birth of the "terroir"

At about the same time, this reflection was also maturing in France, starting from the same cultural background: all European wine territories are heirs of Roman viticulture.

The French scholars made this concept explicit with the term terroir, which began to be used with this meaning more or less from the mid-1900s. Until then, this word was an archaic synonym of soil or territory, not commonly used in modern French. It was an archaism used mostly in agriculture. Oddly, in the XVIII-XIX century the word "terroir" has been derogatory. The "goût de terroir" (terroir aroma) indicated a negative aroma of the wine. "On dit que le vin a un goût de terroir, quand il a quelque qualité désagréable qui vient par la nature de la terre où la vigne est plantée". "It is said that the wine has the taste of the terroir when it has some unpleasant quality that comes from the type of land where the vine was planted". (Louis Liger, “Dictionnaire pratique du bon ménager de campagne et de ville”. Ribou, Paris, 2 t., 449 & 407 p.).

In the 70s-80s, prof. Attilio Scienza committed himself to spreading the concept of viticultural territory as Genius Loci, with a view to highlighting its productive and cultural importance, but also to underline our "birthright", as Italians, of a cultural heritage born in Italy, using a Latin name.

Unfortunately, the world of Italian wine did not understand the centrality of this aspect, as well as the great communication on Italian wine in the world that would have derived from it. Later, when Italian wine-producers began to understand the importance of narrating their traditional relationship between wine and territory, they had to accept the use of the French word “terroir”, which in the meantime had emerged in the world. In fact, our neighbors (unlike us) had understood the importance of this concept first. Then, the word "terroir" was amplified and consolidated universally by Anglo-Saxon wine writers. Today, sometimes, the French claim to have also invented it! Sic transit gloria mundi (as Latins said)

I can't hide being biased. My Latin soul makes me love the term Genius Loci more, also because it seems to me that it explores greater depths! It is so fascinating the image of a genius who gives us favors or misfortune as much as we love and respect our land!

However, beyond primogeniture and words, the fact remains that nothing like the concept of Genius Loci (or terroir) is able to represent the truest soul of artisan wine, from over two thousand years. There are people who say it is something impalpable, difficult to explain in detail or to understand rationally while tasting a wine. On the other hand, it is its nature: in part it is explained by science, but it also has something elusive, complex, easier to understand only with the intuitive side of the mind. Anyway, when I'm doing my work of winemaker, however, I always realize that nothing is more real and alive in our wines than it.

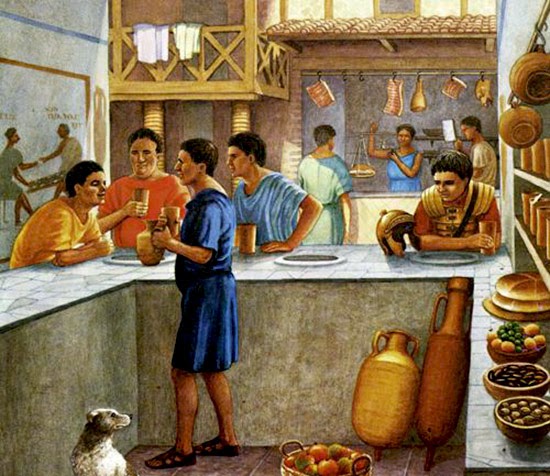

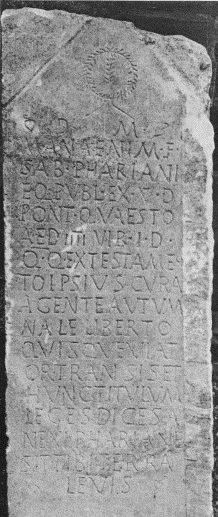

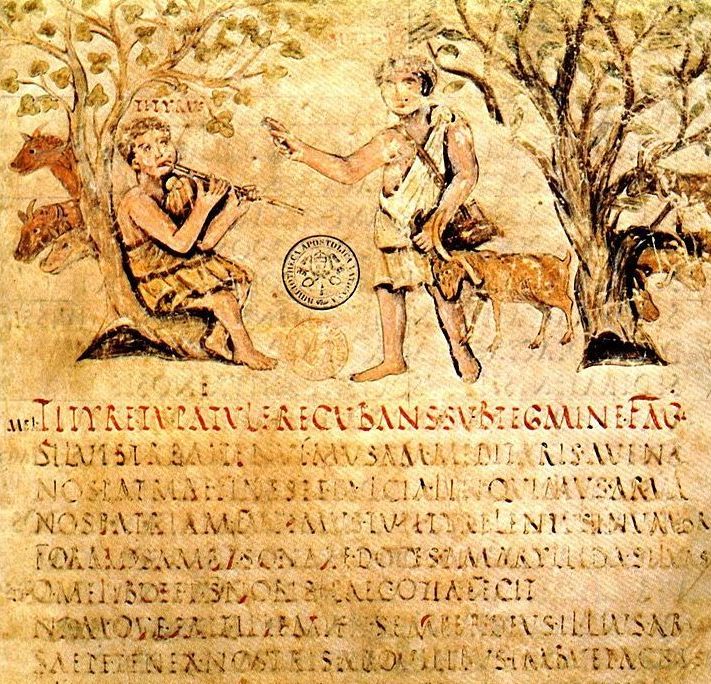

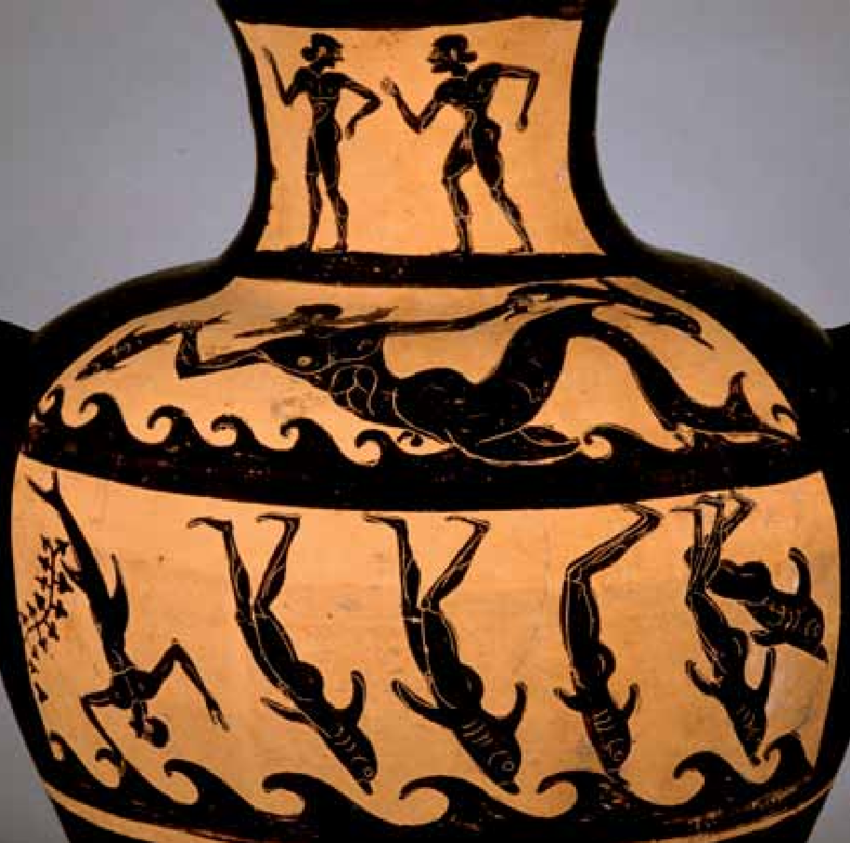

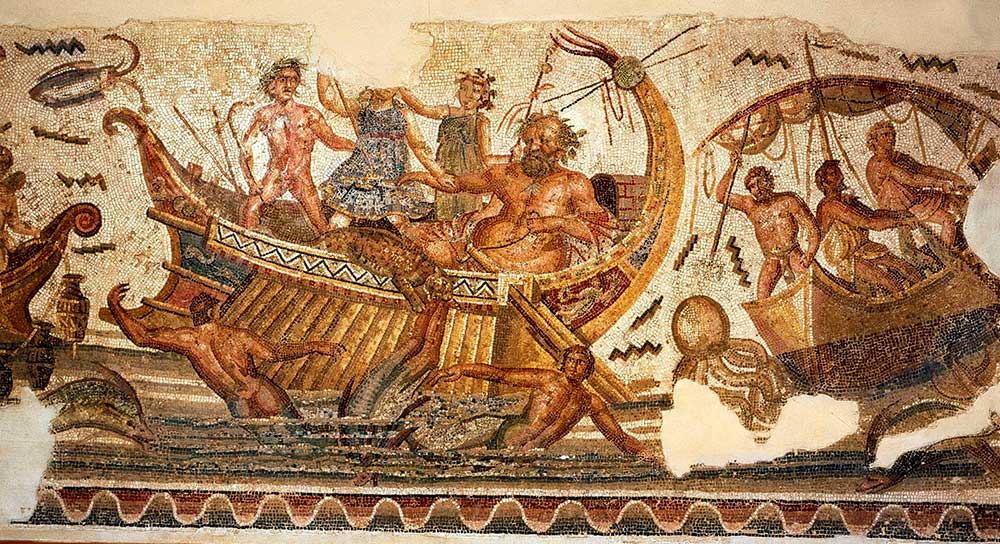

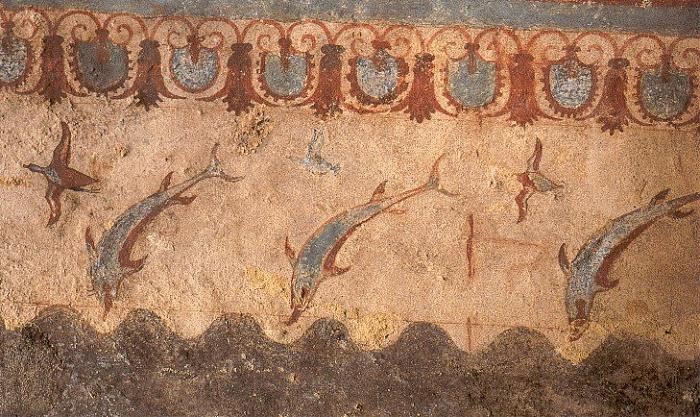

The images without caption are mosaics and frescoes from the Roman era.

Bibliography:

Columella, “De re rustica” , 65 d.C.

Giangirolamo Pagani, 1794, Rustici Latini Volgarizzati, Lucio Giunio Moderato Columella, ed. Vittorio Curti Venezia.

Attilio Scienza et al., 2010, Atti del Convegno “Origini della viticoltura”.

Luigi Manzi, 1883, “La viticoltura e l’enologia presso i Romani”.

Dalmasso e Marescalchi, 1931-1933-1937, “Storia della vite e del vino in Italia”.

Emilio Sereni, 1961, “Storia del paesaggio agrario italiano”,

Marcella Peticca, "Genius Loci: perdita e riscoperta del luogo", 2015, Università di Bologna.

P. Prévost, P. Morlon, J. Salette, "Le Mots de l'Agronomie", 2017, https://mots-agronomie.inra.fr/index.php/Terroir

https://www.romanoimpero.com

We are closed

As known, we are in an emergency Corona virus. So we adjust to the rules and we are closed. if you want our wines, we ship them your home. Write me at info@guadoalmelo.it for info.

We are closed at least until April 3 (inclusive), then we'll see.

The vineyard balance always stars with a good pruning

In these days we are doing the winter pruning in the vineyard, which is the most important of all the works to direct the vines to a harmonious balance. I will try to make you understand broadly how and why we do this work.

First of all, I would like to emphasize that nothing must be improvised in the winegrower's work: we rely on a thousand-years peasant knowledge, then deepened by the studies on the physiology of the vine and its relations with the environment around it. Only a good knowledge allows to respect its balance and intervene in a respectful but useful way.

It is important not to make mistakes in the pruning, otherwise we will not be able to produce great terroir-expressive wines. Making a mistake (or making a bad pruning due to lack of skill or lack of competence) has the result of limiting the expression of the full potential of the vineyard and / or damaging it to such an extent as to shorten its life.

[one_third][info_box title="What happens if the vine is not pruned??" image="" animate=""]

If you do not prune, as happens to wild vines in nature or as it was done in the forms of primitive viticulture, the plant tends to grow a lot and produce many bunches. They are small, not very sweet and not very balanced. It is a grape that is good for feeding wild animals or for making a rudimentary wine.

However, the first winegrowers began to understand with the experience that, by pruning, they managed to produce a better, sweeter grape, and they were able to produce a much more interesting wine. From then on, this practice was no longer abandoned but refined, to the point of becoming almost an art.

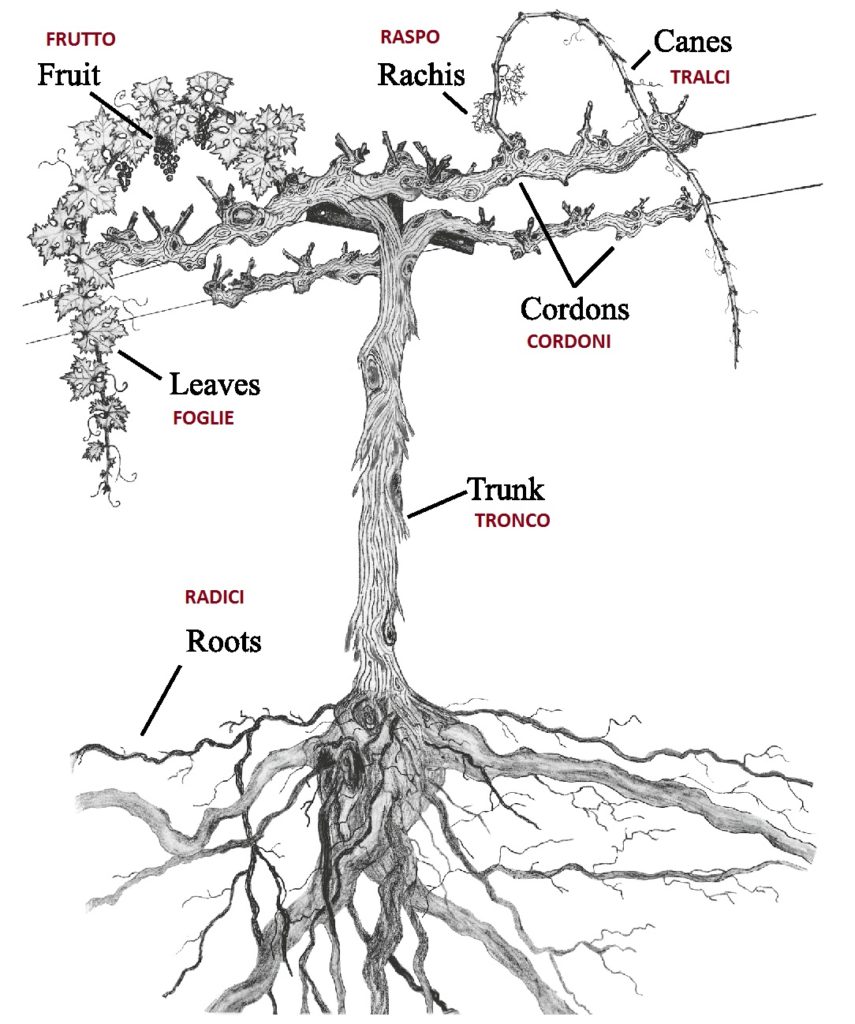

The unpruned vine also has a significant production alternation. It means that a year there is an abundant production, the following year instead there will be very little grapes or practically nothing, and so on (beyond the normal fluctuations of the year production, linked to the seasonal trend).[/info_box][/one_third] In practice, when the vine is on dormancy, we cut the branches of the past year, leaving a certain number of buds. This number is carefully evaluated, because it determines the production of the following year. The number and distribution of the buds also define the living space of the plant, that is what is called the vine training system. It is important because it determines the balance between all the parts of the vine (trunk, roots and canopy), in relation to the environment in which it lives.

The cut should be evaluated vine by vine, vineyard by vineyard. It can only be done by hand, by expert people. No choice is random in the good management of the winegrower: if you have the patience to go through with this post, you will understand it.

However, it is not the only work that acts on the overall balance. So, it must be done with an overview, starting with the birth of the vineyard itself, its story over time and already thinking about the subsequent works. Everything must be integrated in the vineyard management.

When pruning:

Pruning is done when the vine is in the winter dormancy phase.

The time of pruning affects that of the spring budding. The sooner you prune and the sooner the vine will sprout (and vice versa). Generally, we winegrowers want to prevent an earlier budding, because there is often a great risk of bad weather at the beginning of spring. There could be frost or hailstorm, which could damage the shoots. For this reason, generally, we prune as far forward as possible. However, it depends a lot on climate: the risk is maximum in northern Italy, minimum in the south (with all the possible intermediate variables). The big risk for our territory is the frost due by the north or north-east winds.

It must also be taken into account, especially for those who are in colder climates, that some varieties bear winter frost less well if they have already been pruned. In this case, it would be better to wait until the coldest period has passed.

Finally, the winemakers have to deal with their own forces and the size of their vineyards, to calculate the exact times. Pruning must be finished, in any case, before the "vine weeping", i.e. the emergence of droplets from the cutting points of the wood. It is the signal of the restart of the sap circulation in the plant, the first sign of the forthcoming development of the shoots.

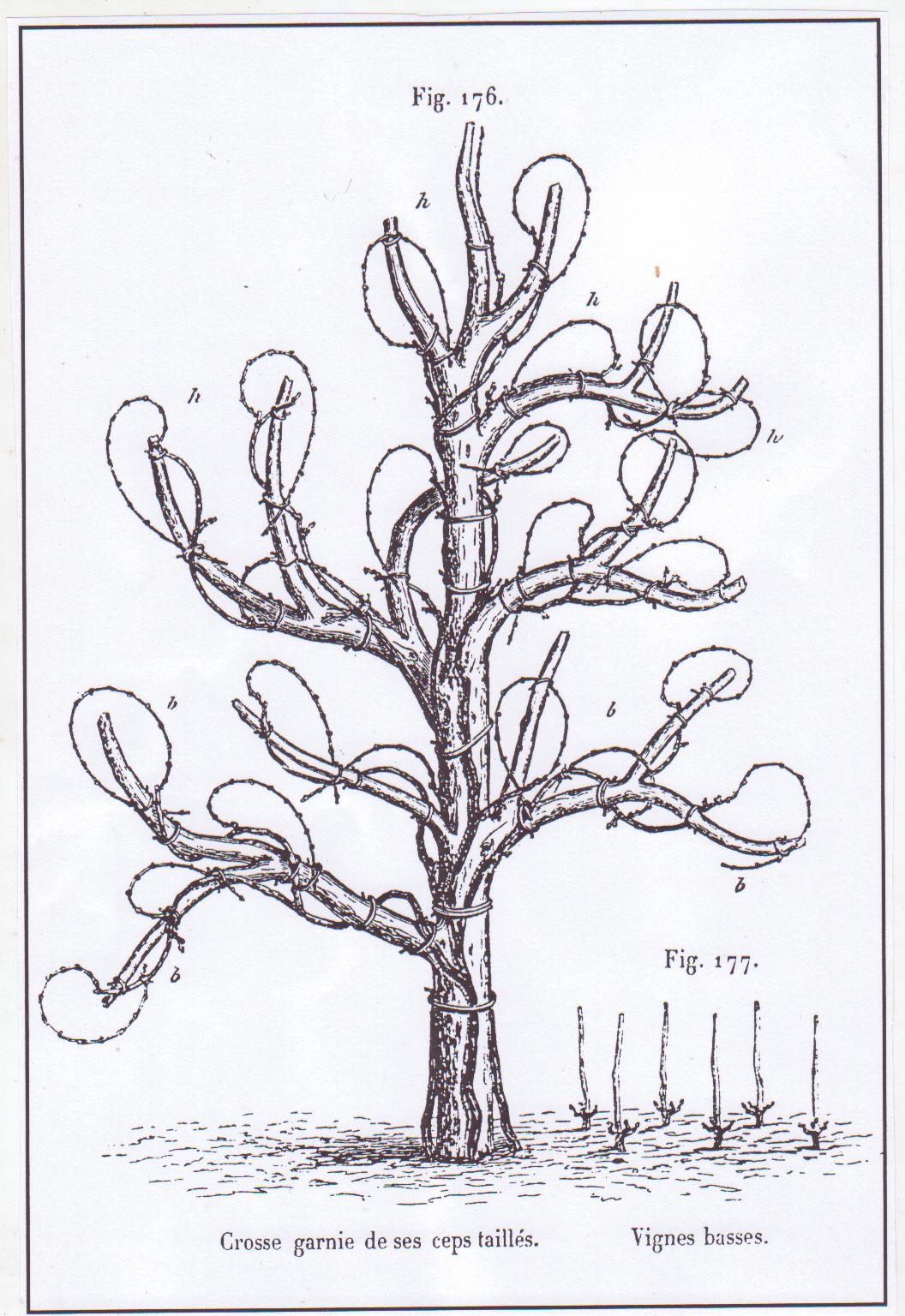

The tools of the pruner.

In the past, the winegrowers used different cutting tools for each region of Italy. The billhook was mainly used in the north. In the center and in the south, different shapes of "pennato" were prevalent (in the drawing: it is similar to a billhook, but with the addition of a second blade. This pruning knife shape dates back to the Roman period). These tools were difficult to wield: it was easy to injury yourself, to injure the plant too much (with the entry of diseases and pests) and it takes strength. In the nineteenth century, the pruning shears (or secateurs) began to be used and the work started to be a little easier. Today we still use them, sometimes electric or pneumatic ones, to reduce fatigue and hand usury. The saw is used only for cuts of particularly large branches, or parts of the trunk.

Pre-pruning is often done for sustainability reasons (as we also do it). It is a very coarse cut of the branches, made with the pre-pruned machine. Then, the pruners will make the handcrafting precise cut. Pre-pruning eliminates the waste of time and the effort to untangle the long branches, wrapped around the wires and between them. Speed is important because, as written, the working time frame is often not very wide.

What do we do with the canes?

As tradition, we break up the branches cut in the vineyard and use them to make compost, useful for recovering organic substance. Someone burn them, but it is not environmentally friendly and it is also a waste. The vegetable compost, which we also do with all the other plant remains (stalks, grass, etc.), contributes to enriching the soil above all with nitrogen, calcium and potassium. The high biodiversity index of our vineyards favors the mineralization of the organic substance and the correct distribution of these nutrients.

Let's go into detail:

A very delicate and complicated balance

The vine directs its energy to different purposes: the growth of all its parts (woody and green), the formation and development of the bunches, the accumulation of sugars and other organic compounds in the grapes, the storage of reserve substances. All these functions are fundamental for an optimal vine balance (and the vineyard as a whole) so that it grows well, gives good grape and has a long life.

Pruning (with other subsequent works) acts on the regulation of the vigor of the vine, directing its energy first of all to the production of balanced grapes, but it is always necessary preserving a harmonious development of the plant.

The pruning is heavily conditioned by the territory (climate and soil), variety, rootstock, etc. A well-knowledge of these all elements are indispensable to do the optimal choices. Depending on the different conditions, it may sometimes be necessary to stimulate the vigor of the plant, sometimes it is better to limit it.

A too vigorous vine tends to grow a lot in all its parts, producing a lot of grapes, but they will be low-quality. Even a too weak vine will not produce the best wine it could express. It lacks energy and cannot accumulate all the necessary organic compounds in the bunches. Furthermore, it would not feel good in general: it would not be able to carry out the vegetative renewal, to deposit the reserve substances in the perennial organs. This would compromise the balance of the plant, including the optimal work of the roots, with important repercussions on the present and future life of the vine.

In both cases, there would be produced poor quality grapes (for opposite reasons), which will ripen badly. It is not just an unbalanced accumulation of sugars (too many or too few). It will also be a grape that will produce a wine with an unbalanced acidity, which could maintain herbaceous characters, which would not be able to develop aromatic complexity, etc.

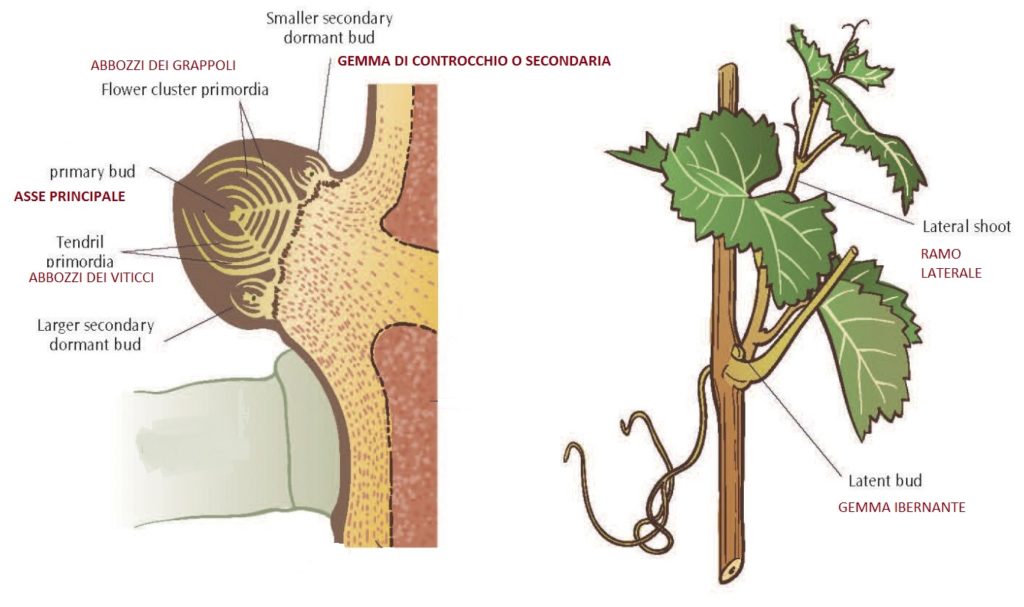

[info_box title="Life cycle and buds" image="" animate=""]The vine life is a circle: it sleeps in winter, wakes up in spring, sprouts, grows, bears fruit and goes back to sleep. However, it is not a closed cycle: each year it is closely connected to the previous one. The buds that will sprout next spring were formed the year before. They are called dormant or latent buds.

The dormant buds wake up in the spring, sprout and form new canes. Leaves, clusters, tendrils and new buds are born on the internodes of the canes. There are two kinds of buds: the latent and the lateral one. The latter is active in the same vintage in which they are born: it will develop the lateral shoot, during the spring and summer. For now, however, it doesn't interest us.

If we slice a dormant bud in its birth year and look at it under a microscope, we see that inside there is the primordia of the future cane, on which there are the primordia of the future bunches. Their number indicates the fertility of the bud.

So, do you understand why the more or less good performance of the previous year also affects the production of the next one? Fertility depends on many factors, such as the variety, the vigor of the plant or of the single cane (it grows with the growth of vigor but the two extremes instead, too much or too low, both reduce fertility), etc.

From this microscopic observation, we can also see that there is not only one future cane in the bud. In the center there is one, the largest, called primary bud. There are two other (or one) smaller ones nearby. They are called secondary buds. They are reserves: if the primary bud dies, the secondary ones develop, which are generally not much fertile.

Not all dormant buds, left with pruning, will develop. Some die. Others can remain latent. They are incorporated in the growing wood and can develop even after several years. These secret survival reserves are awakened by particular events, difficult for the vine life (blows, frost, drastic pruning, etc.). When they wake up, they form low, sterile branches, called suckers. In general, the vintners eliminate them with the green pruning. Sometimes they come in handy, because these low canes can be used to reform structural parts of a plant that have been damaged by trauma or pests.[/info_box]

The number of the buds

The number of the buds per vine changes the flow of vigor of the plant.

How many buds to leave with pruning depends on many factors. In general, too high a number of buds would cause an excess of grapes produced. Too low would induce too vigorous growth of the green parts, subtracting energy from the ripening of the bunches. However, it depends a lot on each particular situation: variety, rootstock, climate, soil, density of the vines, previous production, etc.

The best way to understand the optimal number depends only by experience and knowledge. It is necessary to live your own vineyard, make small tests and accurate observations, carried out over the years, which make us understand if we are working well or not.

The vine balance must be as continuous as possible. Excessively drastic changes, even if corrective, can sometimes be more harmful than useful. They alter too sharply a now set balance. For this reason, it is important to evaluate certain changes in an integrated way, considering all the year works in the vineyard.

Short or long pruning?

Another key element of pruning is whether it is done in a long or short way. This depends on the fact that the buds do not always have the same fertility along the cane. It has been known since Roman period, as wrote by Columella. It depends on the climate but also on the varieties.

Why the climate?

In colder climates, the buds on the first internodes are not complete. They do not form the primordia of the bunches (in scientific terms, they do not well differentiate). They will therefore be little (or not at all) fertile. This happens because they are the first to develop, in early spring. In these climates, this is an unfavorable moment: there are difficult environmental conditions and the plant is weak. The same happens in summer, for the buds of the last internodes. The most fruitful are those that arise in the best moment of life of the plant. They are located in the intermediate part of the cane.

In the warmer territories, as in our case, this usually does not happen. The climate is good from the start, so the buds of the first internodes are also fertile. In this case, it is always better to prune short. A long pruning leave too many fertile buds and too much production would occur.

Some varieties behave differently, regardless of the climate.

Where possible, the winegrowers usually prefer short pruning, which generally gives a better balance between leaves and bunches, with better ripening. In this case, cutting the cane, a short stump remains, called spur.

Long pruning is instead done more frequently in the north Italy, in cooler climates, or it is necessary for some varieties. When we cut, a longer piece of cane remains, with more internodes.

There is also mixed pruning system. In this case, we cut some short and other long canes. It is necessary for certain forms of grapevine training system, when we need to have fruiting branches and to renew the woody parts.

I continue to write "in general" because these aspects are very variable and only experience and knowledge of one's situation lead to the best choice.

Grapevine training system.

So far, I have described the production pruning. It changes also according to the form of vine growing.

In the first years of life of a vineyard, pruning does not have productive purposes but serves to make the small vine grow well and to take it to the shape of the chosen training system.

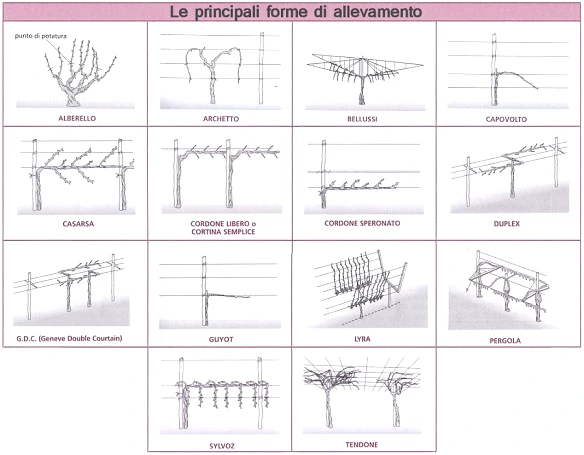

How do you choose the training system? It depends on the territory (over all, the climate) and the varieties. In Italy there are many traditional training systems. Each choice is not accidental.

A substantial difference is the height of the trunk of the vine. This element greatly changes the balance of the plant. Inside the trunk, there are vases that carry what is absorbed by the roots (water and mineral salts) and, vice versa, what produced by the leaves (organic substances and energy). The longer the trunk, more energy is lost only for these transfers, subtracting it from the rest. However, there are also different needs, which can make more or less useful to have the trunk higher or lower. For example, where the vigor is not a problem, but there are risks of humidity and frost, it may be more useful to have the trunk high, to distance the bunches from the ground.

The training system and pruning also affect the arrangement of the canopy. If you notice, there are vineyards with vertical canes, in others they are more or less inclined. Sometimes, they are drooping. This orientation is not accidental. The vegetation activity, the vigor of a cane, is favored by the vertical position. This is generally preferred where there are limiting environmental conditions for the vine. The more the branch is bent with respect to the vertical, the more it loses its vigor. So, it is often found in the territories where you want to counteract too high a vigor. It is a phenomenon that also depends on the complex internal transport of the plant.

There are also training systems where the branches are more or less bundled together, willing to make circles, pergolas, etc. In general, the canes that are too united and overlapped favor the stagnation of humidity, the diseases, limit the absorption of sunlight by the leaves, etc. All these choices depend on the particular situation of the vineyard. For example, in very dry climates, overlapping limits water loss, reducing the transpiration. Where there is little sun, in humid climates, it is better instead to arrange branches and leaves so that they take maximum solar energy, without too many overlaps that favor damp (and therefore diseases and rots). The variables are many.

Our training systems and their pruning.

Our climate is mild-Mediterranean, hot and arid in summer, a little rainier in winter and spring. Our alluvial soils are over all lean and well-drained. In this condition, the best grapevine training systems are the low ones, subjected to short pruning, sometimes long (for some varieties), with vertical canopy. We have the Guyot and the spurred cordon.

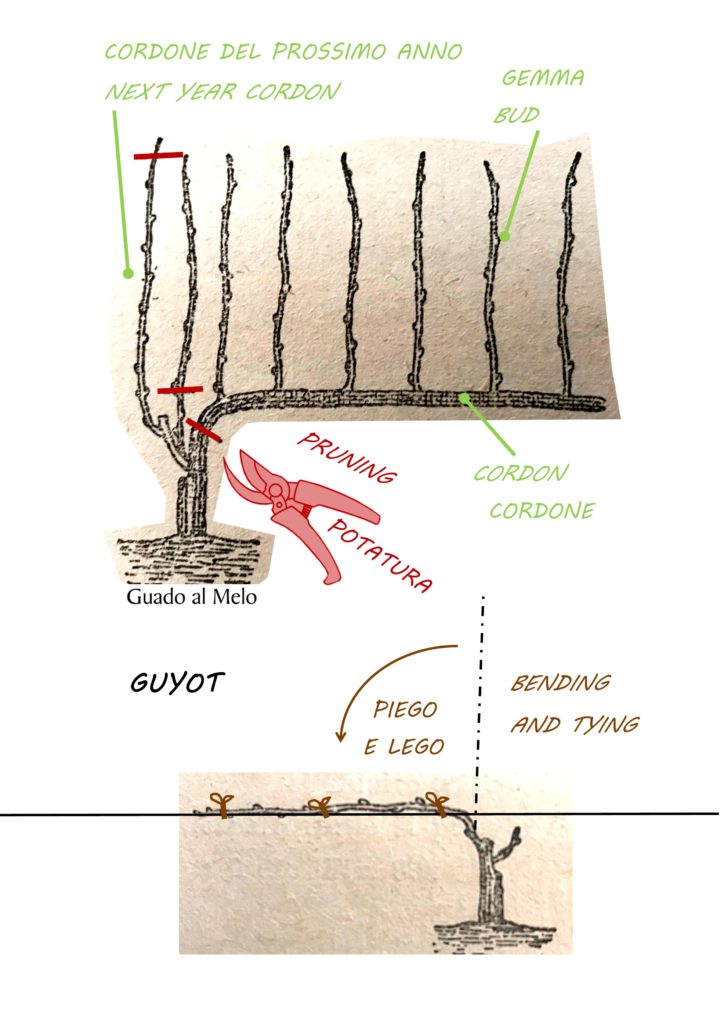

Guyot: it is a very ancient traditional Italian system. It was incorrectly attributed to a French agronomist, Jules Guyot, who described it and spread it in his country in the 19th century. It is a low-production and a high-quality form. It is found in many parts of Italy, from Sicily to Piedmont. It is a mixed pruning system. It is perfect for those varieties that are more fertile in distal buds. It isn't an expanded form, suitable for not very fertile and drought soils, where the vine generally has a limited development. In the pruning, we cut a long cane, from which the future fruit-bearing canes will develop. A second cane is pruned at spur, which will serve for the next year.

Guyot: it is a very ancient traditional Italian system. It was incorrectly attributed to a French agronomist, Jules Guyot, who described it and spread it in his country in the 19th century. It is a low-production and a high-quality form. It is found in many parts of Italy, from Sicily to Piedmont. It is a mixed pruning system. It is perfect for those varieties that are more fertile in distal buds. It isn't an expanded form, suitable for not very fertile and drought soils, where the vine generally has a limited development. In the pruning, we cut a long cane, from which the future fruit-bearing canes will develop. A second cane is pruned at spur, which will serve for the next year.

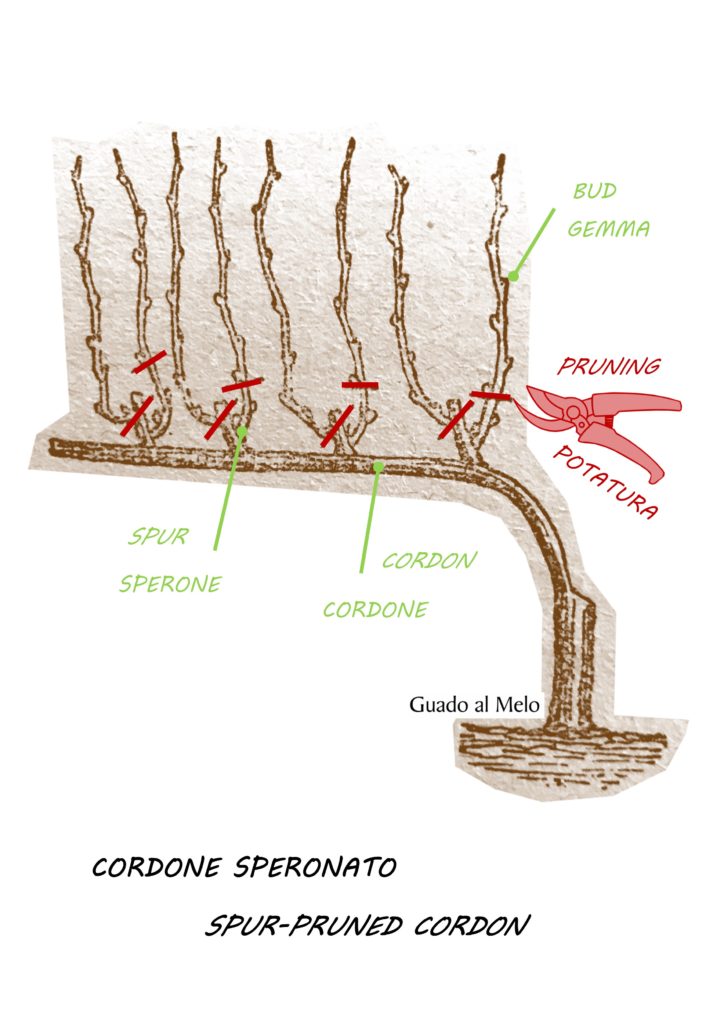

Spurred cordon: it is also traditional and it derives from Guyot. In this case, however, there is only the short pruning. It is suitable for low or medium fertility soils, even dry, and for those varieties that have good fertility on the proximal buds (the first ones). It is frequent in Tuscany and other Italian central regions. During the first years of the vineyard, the best cane is placed horizontally and it becomes a structural element of the plant. The gems on the underside are eliminated. In spring, fruiting canes will form from the upper buds. The following year, each cane will be cut into a spur, forming the cordon. Each subsequent year, it will be cut with short pruning. This system has been successful and has spread due to the excellent quality management of the vineyard, but also for simple and fast pruning.

Spurred cordon: it is also traditional and it derives from Guyot. In this case, however, there is only the short pruning. It is suitable for low or medium fertility soils, even dry, and for those varieties that have good fertility on the proximal buds (the first ones). It is frequent in Tuscany and other Italian central regions. During the first years of the vineyard, the best cane is placed horizontally and it becomes a structural element of the plant. The gems on the underside are eliminated. In spring, fruiting canes will form from the upper buds. The following year, each cane will be cut into a spur, forming the cordon. Each subsequent year, it will be cut with short pruning. This system has been successful and has spread due to the excellent quality management of the vineyard, but also for simple and fast pruning.

In our historic vineyards we also have:

Head-trained system (In Italian, “alberello”): it is traditional in Italy in the places of ancient Greek or Phoenician culture. It is one of the oldest forms. It is suitable for extremely dry, poorly fertile, or windy or very cold soils, where it is convenient to have a contained vegetation that remains close to the ground. It is at the lowest point of the productivity scale, with the highest sugar levels. It is found in Valle d'Aosta (which is semi-arid) and Sicily, for opposite climatic reasons. Pruning can be very short, as we do (the Greek system, the vites capitatae described by Columella), short or even long or mixed, depending on the territories and varieties.

The pergola: the oldest representation is in the Egyptian tombs, where it is represented in the shape of a tunnel, as we have reproduced it at Guado al Melo. In Roman times, horizontal pergolas (called jugatio compluviata) were created to cover avenues and terraces, described by both Columella and Varro. Many variations developed, some more suitable for table grapes, others for wine production. It is a high-vine shape, with the branches well distributed on a more or less inclined surface, to capture the sun's rays to the maximum, avoid stagnation of humidity, but do not give excessive vigor. In Italy, for wine production, it is widely used in mountain areas, such as Trentino. Pruning can be of different types, depending on the territories and varieties.

The trained-to-a-tree system or married vine: one of the oldest forms ever, that of our primeval tradition. I have already talked about it at length (here, here and here). It was not pruned at all, in the primitive viticulture. Later and until the twentieth century, it was subjected to long and rare pruning (every two years or even three). It was the system that guaranteed the most longevity of the vine, which frequently became over hundred years old (before phylloxera arrived from America, to complicate the life of the winemakers).

At Vinexpo Paris, with the TreBicchieri WorldTour

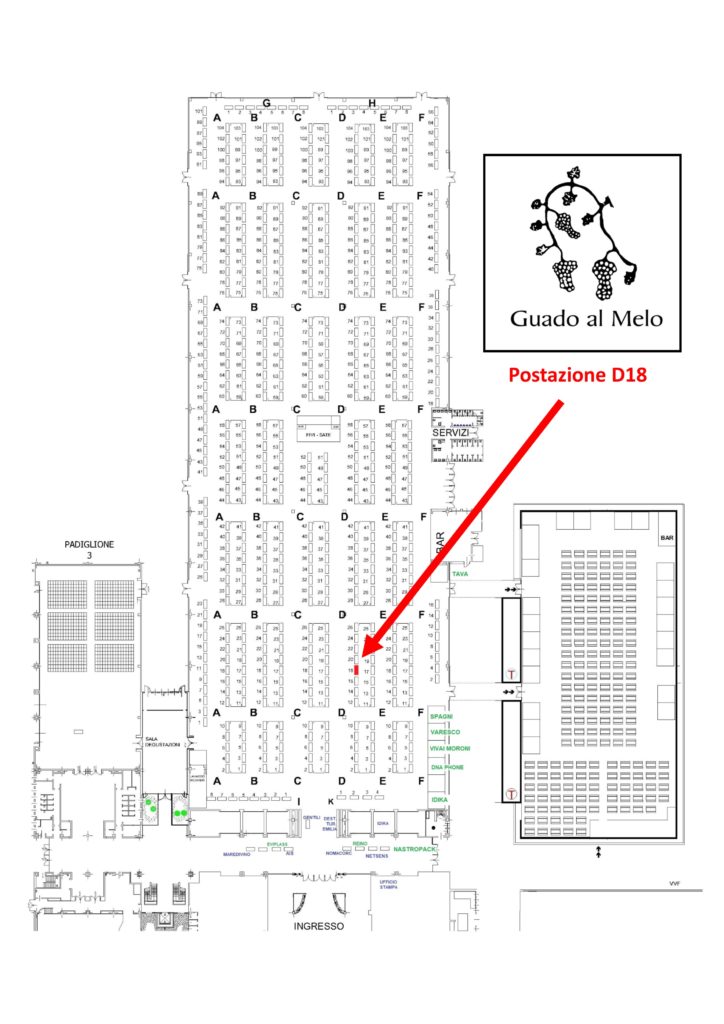

We’ll be in Paris Vinexpo, on 11th February with the TreBicchieri World Tour of Gambero Rosso.

There will be, overall, the tastings of the prizewinning Criseo Bolgheri DOC Bianco 2017, and other our great red wines.

Vinexpo Paris, Porte de Versailles

Pav. 7.2

Tuesday 11th February , h. 2.00-6.00 PM

Ancient Rome: a lost in translation vineyard

"Where could we better start if not from the vine, compared to which Italy has such an undisputed supremacy, that it gives the impression of having overcome, with this single resource, the wealth of every other country, ...?" Pliny

In addition to Pliny, Horace also says that the Romans considered viticulture as one of the nation's greatest economic resources. Cato places it in first place among the more profitability crops. We are not surprised: Italy is a great land for the viticulture and has a great production still today.

You will think: what can be said of Roman viticulture that has not already been already said and repeated?

In truth, Roman viticulture has often been misrepresented due to linguistic and cultural misunderstandings, although it has been well described by Latin authors (our sources: see here) and examined far and wide by scholars of all centuries. This fact has often prevented from understanding its original and absolutely distinctive trait: the cultivation of the vine "married" to the tree (or vine training system to a tree) of Etruscan origin, a form that will remain in Italy until the first half of the twentieth century. This cultivation system was also present in other ancient civilasations but in Italy it has played a particularly important and lasting role for millennia.

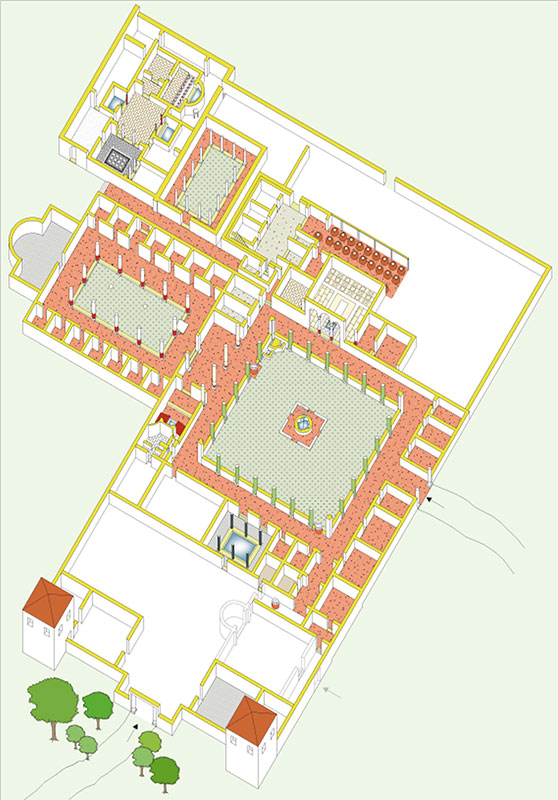

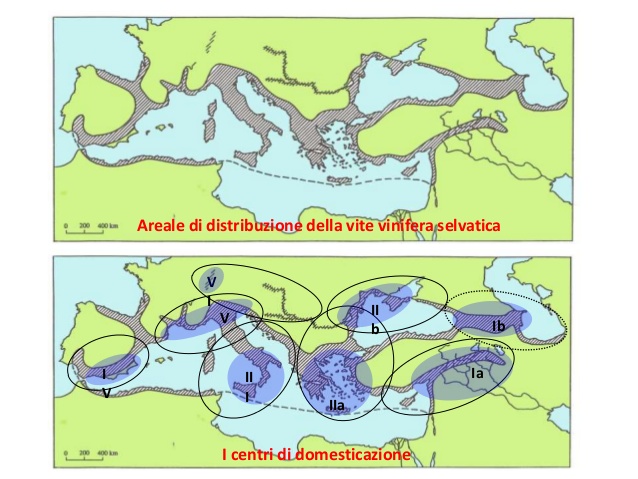

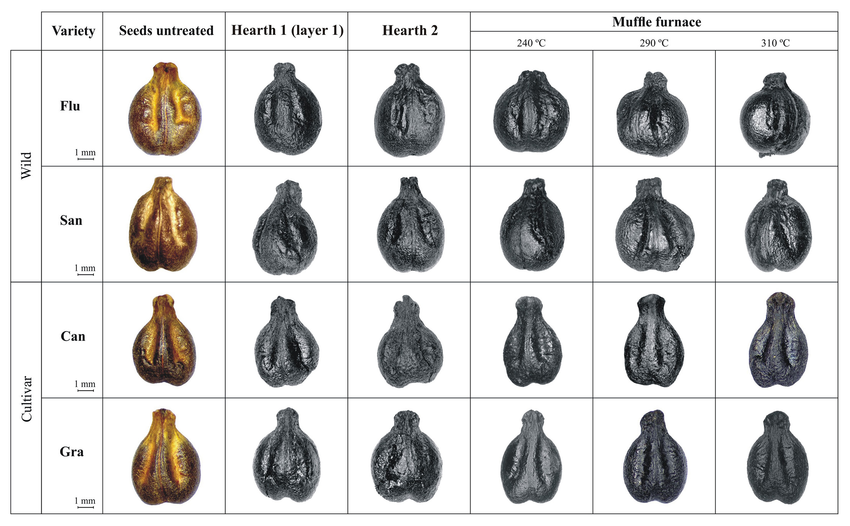

Viticulture in Rome, as for almost all Italic peoples, is very ancient. Ever since man stepped our lands, he has always collected wild grapes in our Mediterranean woods. In Rome, the transition to advanced viticulture seems to have occurred due to Etruscan influence. I have already written in more detail here on the origins of viticulture in Italy.

The original Roman viticulture was therefore the same as for the Etruscans, a training system based on the natural way of wild-vine growth. In the woods, in fact, it uses trees as a support to reach the light. In Etruria maples were mainly used, in Rome mainly elms. In Latin, this cultivation system was called arbustum vitatum (vine trained-system to a tree or alberata), with the vitatum often omitted. More poetically, the term vitis maritae was also used, "married vine" (vine married to a tree). I have already described these aspects in more detail here.

If we want to imagine the classic agricultural landscape of the Roman era, we must think of a countryside with vines married to trees, arranged in rows or quincunx (like the number 5 on a dice), with intermediate strips of wheat (or other crops). There were also the olive trees.

This agricultural world is not so distant from us, even if forgotten today. Still at the beginning of the twentieth century, Chianti wine was produced by a very similar model of viticulture, well represented in this work by Raffaello Sorbi (1893): vineyards with "married vines" (system called "testucchio" in Tuscany, at the time), alternated with strips of wheat (or other crops), managed by farmers in sharecropping. The oxen with the muzzle were also identical (Pliny also recommends it, you will see).

Rome will incorporate the Greek viticulture training-system only later: the low vine cultivation system, without support or with a "dead" support (the pole), then carrying on both.

Lost in translation.

I refer to the title of a well-known film from several years ago, "Lost in translation", which gives a good idea of what happened with the viticulture of ancient Rome, often misrepresented due to translation and cultural problems.

Unfortunately, it is also our fault. Modern Italy wine world has not paid much attention to its immense historical and cultural heritage, often with a superficial approch. Often the narration of the history of wine (including ours) in the modern era has been left to foreign authors, unrelated to our culture, who did not have sufficient instruments to understand it.

Roman viticulture has therefore often been identified only with the Greek vine-training system, the low vineyard. Scholars or popularisers, unrelated to Italian culture and / or without in-depth agricultural skills, did not even know the existence of the "married" vine. Others have considered it absolutely secondary, a primitive form of little interest, soon supplanted by Greek vine training-system, considered more advanced. Whenever the term vinea (vineyard) was found in the Latin authors, it was assumed that it referred to the low vineyard. Hugh Johnson, for example, cites the existence of the "married" vine, but he writes that "the ancient authors never talk about it" (!).

The Latin term specific to the alberata or "married" vine, arbustum, has been widely misunderstood. English authors often have translated it as a plantation of trees or woods or grove, so French ones, as Apollinaire (bouquet of arbre), and various German writers (Jungholz). They did not notice the absurdity to translate Varro's works, for example, writing that a "grove" produces certain quantities of wine and wheat!

Latin poets wrote about the "married" vine, too, never about the low vineyard. Catullus was the first who describes the vine and the elm as wife and husband (in the Carmina). In the Augustan era, this system is often cited by Virgil and Horace. The one who talks about it most is Ovid, who frequently uses the "married" vine as a metaphor for love in Amores, Fasti, Heroides, Tristia and Metamorphoses, in the Vertumnus and Pomona's tale (see here).

As previously mentioned on the origin of viticulture in Italy (here), there have been several multidisciplinary studies (between archeology, linguistics and viticulture) in recent decades that have tried to shed more light on our viticultural origins. Above all it the work of Paolo Bracali (University of Perugia) has clarified the meaning of the Latin terms related to the vine and their change during the long Roman history.

Vinea or arbustum?

Cato, the first of the agrarian Latin authors, is quite clear when he writes that to make a good vineyard it is necessary "that the trees are well married to the vines and that they are in sufficient numbers". The Roman vineyard, from its origins and still in Cato's time, was made only with vines married to trees. He indicates it with the generic term vinea (vineyard) or, when he wants to underline the form of cultivation, the more specific word arbustum.

[one_third][info_box title="" image="" animate=""]*Cicero tells the story of Attus Navius, a young pig guardian with divinatory skills. One day he lost a sow in a vineyard and he vowed to Jupiter, if he found it again, to offer him the largest bunch. So, it happened and, to fulfill the vow, he divided the vineyard into different parts and interpreted the flight of birds for each one, according to the divinatory Etruscan uses. In doing so, he found a cluster of incredible size and beauty to be given to the god. The young man then became the official augur of the first Etruscan king of Rome, Tarquinius Priscus.

This myth is considered at the origins of the Roman rite of the auspicatio vindemiae. Before the harvest, Flamen Dialis, the high priest of Jupiter, offered the god a bunch chosen from a public vineyard. The rite served to ensure a good harvest and was the official start at the time of the harvest. So, the period of this rite varied every year. [/info_box][/one_third]Until the late Republican era, therefore, whenever the word vinea is found, it refers only to the vine planted with trees, the traditional form of Roman viticulture. Many of these authors do not explain how the vineyard is made, they have no agronomic intent, but we can also notice it from some details. Cicero, for example, tells a myth in which a boy brings pigs into a vineyard *. It can only be a vineyard made with "married vines", since it is practically impossible to think to graze pigs in a low vineyard with ripe grape (they would have eaten it!).

Phaedrus, who translates and readapts Aesop's fables in the first century BC, uses the term vinea alta (tall vineyard) in the famous history of the fox that cannot reach the grapes. A change is beginning. He still uses the word vinea in the ancient way, but he feels the need to add the alta (tall) adjective. Maybe, is he afraid of not being understood?

In fact, Rome had now annexed several territories that had been Greek colonies, in the south of Italy, where the vines were cultivated low, without a support or sometimes supported by a stake. This other cultivation system also became part of Roman culture. The need not to confuse them led to a linguistic change that seems to be fixed in the last decades of the first century BC.

Varro seems to be the first to use two distinct names to indicate the two cultivation systems. From then on, in Latin texts, the word arbustum remained to indicate the "married" vine system, while vinea became the preferential term for the Greek low vineyard. The vinetum (vineyard) included both, as well as sometimes vinea (... just to not make it too easy ...).

So, you understand the difficulty? It was easy for inexperienced translators (on viticultural aspects) to get lost, especially by mistaking the arbustum for a grove, not even realizing that they were talking about a vineyard.

Today in Italian, vinetum is become vigneto, vinea is become vigna. They are synonyms, both of them means "vineyard" (in general). The arbustum vitatum is become vite alberata. But this vine-training system disappeared almost completely in Italy in the mid of twentieth century and today very few Italian people remember it.

Tall or low vineyard?

From the late Republican Era and especially in the Imperial Epoc, therefore, both forms of viticulture were present.

In many texts of wine history there is a schematic subdivision according to which the low vineyard was typical of the large slave villae (the big estates) with an intensive and higher quality production. The arbustum is relegated to more primitive or less specialized contexts. In truth, this interpretation seems to reflect a twentieth-century concept of viticulture rather than an understanding of the historical epoch.

The studies of the last decades, in fact, have led to reconsider this model. The concept of specialization and intensive cultivation in Roman times was different from the modern one. Promiscuous agriculture was prevalent even in large villae. Furthermore, the presence of one or another form of viticulture seems to respond more to the cultural tradition of the place than to the estate dimension or the quality of the wine (with due exceptions), as witnessed by Virgil, Pliny the Elder and many other authors.

For example, Pliny the Younger (nephew of the other Pliny) had large properties in the upper Tiber valley, which earned him huge profits thanks to the sale of wine in Rome. Pliny says that his farmers used to cultivate "below and above", where "above" means the "married" vine and "below" cereals, in line with the oldest local tradition. Pliny, telling of his activity as a lawyer, uses this agricultural metaphor that testifies to promiscuous agriculture: "As in agriculture I do not cultivate only the low vineyard (vinea), but also the tall one (arbustum), and not only the "married" vines (arbustum) but also the fields and in the same fields I not only sow spelled or wheat, but also barley, fava beans and other legumes, so in the discussion of a lawsuit, I broadly use different topics as if I were sowing, to harvest what will be born ".

There could therefore be been some variability in the vineyard choices. However, the prevalence of local tradition is also demonstrated by the fact that the most ancient wine-growing cultural frontiers remained more or less the same, in Italy, from ancient times until the twentieth century, as emphasized by most of the Italian agricultural historians. Generally speaking, the "married" vine remained predominant in central and northern Italy, where the Etruscan tradition had arrived in the past, including neighboring peoples influenced by them. The low vine remained prevalent in southern Italy, where there was the ancient Greek viticultural culture. (see here)

In modern interpretation, the "married" vine has often been linked to the production of a poor-quality wine. The Romans, however, didn't think so. Pliny the Elder testifies that the most renowned wines of his time, the famous wines from Campania, capable of very long aging, derived precisely from "married" vines.

He is an advocate of the "married" vine compared to the low vine, as well as Columella. The Latin authors list a series of advantages, the same cited by Italian authors till the beginning of the twentieth century. Numerous subsequent Italian historical and literary sources, from the Edict of Rothari (645 AD) to the nineteenth-century works, indicate the "married" vine as the most suitable for the economy of the farm and the interests of the owner.

He is an advocate of the "married" vine compared to the low vine, as well as Columella. The Latin authors list a series of advantages, the same cited by Italian authors till the beginning of the twentieth century. Numerous subsequent Italian historical and literary sources, from the Edict of Rothari (645 AD) to the nineteenth-century works, indicate the "married" vine as the most suitable for the economy of the farm and the interests of the owner.

The grapes, kept away from the ground, were more protected from frost and humidity. The branches of the tree protect (in part) grapes from other adversities, such as hail. Furthermore, it was considered a considerable advantage to be able to exploit the same plot of land for multiple uses. The cultivation of wheat, or other crops, is easy between the rows of the tall vineyard. Animals can be grazed there for most of the year, without risks for grapes or sprouts (unless there were other crops in the middle to protect). At the time, it was common for the owner to rent the pasture also to external shepherds. In the low vineyard the pasture was possible only during the period of vine rest. In addition, the "married" vine had no need of fences and hedges, being the grape more protected even from wild animals. Only large livestock is dangerous for tall vineyards. In fact, Pliny recommends putting muzzles to oxen when plowing the soil.

When Cato makes his famous ranking of economically most interesting crops, he reminds us that the "married" vine gives double profitability. In fact, he puts it in first place as grape production, but it also returns to the eighth place thanks to the support trees: the leaves as fodder, the pruning of the branches like firewood, the fruits in case of utilize of fruit trees (Cato often mentions the use of the fig tree). This passage was one of the most misrepresented: the vinea in the first place was interpreted as a low vine and the arbustum, in the eighth place, as a grove.

There are not only advantages. The Romans themselves recognized the difficulty of the vineyard works. Pliny tells that, at the origins, King Numa Pompilius introduced the obligation of pruning vines, but the Romans did not want to climb trees, even very tall, for fear of falling. Since then, the use of guaranteeing the funeral expenses to the vintners was introduced in the employment contract. Aside from the myths, Columella cites the Saserna family, owners in the Cisalpine Gaul, who found this system too expensive.

In the following centuries (especially in the nineteenth century) the dispute, that will divide the experts between detractors and supporters, will continue. Several negative aspects have been recognized such as the shading of the vines, the competition between the two species (in not sufficiently fertile soils) with the production of poor body wines, the slowness to achieve an optimal grape production, pruning and higher harvesting costs, the impossibility of even a minimal mechanization, ... The plant disease called graphiosis contributed to abandon this traditional form in the 20s of the twentieth century, causing the death of most of the elms. Simply, there wasn't more space for the "married" vine in the modern specialized viticulture. The peasant ancient world was already sunset.

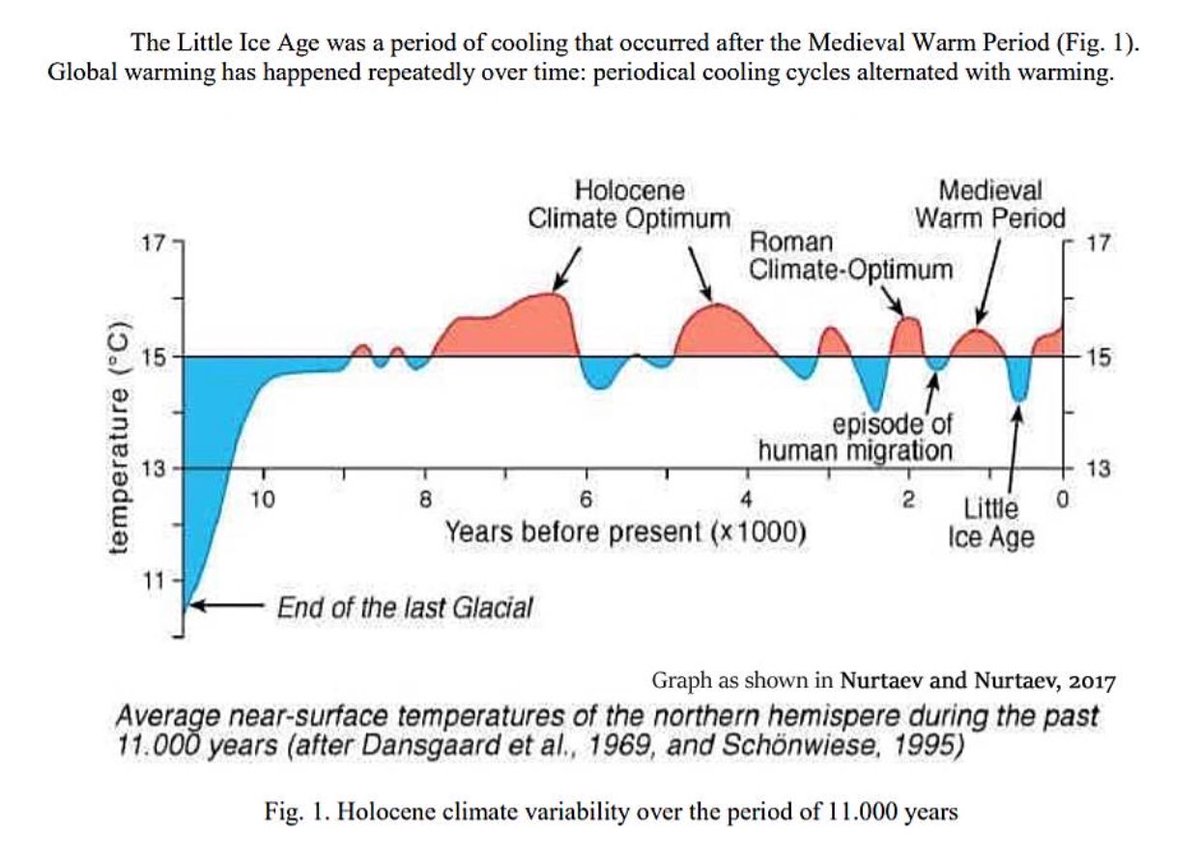

Finally, I would like to remind you that the Roman era, especially in the Imperial phase, was characterized by a very hot climatic period. Today, with the changes in the climate going on, we have already realized that we need to review the production balance of just twenty-thirty years ago. We cannot exclude a priori that a high-producing viticultural form, if well managed and in the appropriate climate and soil, cannot however produce good quality wines. We must remember that Columella testifies how, at the acme of their viticulture, the Romans had a clear understanding of the concept of the link between productive balance and wine quality. This aspect will be "rediscovered" only several centuries later.

Finally, I would like to remind you that the Roman era, especially in the Imperial phase, was characterized by a very hot climatic period. Today, with the changes in the climate going on, we have already realized that we need to review the production balance of just twenty-thirty years ago. We cannot exclude a priori that a high-producing viticultural form, if well managed and in the appropriate climate and soil, cannot however produce good quality wines. We must remember that Columella testifies how, at the acme of their viticulture, the Romans had a clear understanding of the concept of the link between productive balance and wine quality. This aspect will be "rediscovered" only several centuries later.

The "married" vine around Europe (and more).

I have already written about the long "career" of the vine married to the tree in Italy (here). One of the great contribution of Rome was to have spread viticulture in other parts of Europe, through its legionnaires. It was taken for granted that it was only the low vineyard. In reality they also spread the "married" one. In fact, there is a trace of it in the viticultural history of other European territories.

I also remember that other systems of tall vine growing, with poles or pergolas, were always spread by the Romans. They are still present in many parts of Europe.

There are several traces of the ancient "married" vine tradition in France. The tall vineyards (in general) are called hautains. The "married" vine was present in the Middle Ages in numerous territories, for example in Picardy or in Provence (on walnut trees). In the 14th century, there are documents demonstrating its spread to Avignon. Olivier de Serres in "Le théâtre d’agriculture et mesnage des champs" still testifies to its presence in the seventeenth century, especially in Brie, Champagne, Burgundy, Berry, Dauphiné (on cherry trees), Savoy and in the Rhone valley. Until the beginning of the twentieth century, they could still be found mainly in Haute-Savoie and in the area of the western Basque Pyrenees. It disappeared completely after the phylloxera crisis.

In north-western Portugal, the tradition of the tall vineyard still remains, with poles but sometimes still the real "married" vines, with the name of viña de enforcato, in the production area of the vinho verde.

In Spain the "married" vine has not left traces in the viticultural tradition, although we know that it was brought there by the Romans. In particular, there is direct evidence from Columella, who introduced it in its properties in Baetica. Today, there are only other forms of tall vineyards in Galicia and the Basque country.

The very ancient cultural imprint has remained at least in a widespread proverb, which says: "no se le pueden pedir peras al elmo", "you cannot ask the elm for pears", also quoted by Cervantes in Don Quixote. In Portugal there is a very similar one: "Não pode o ulmeiro dar peras", "the elm cannot give pears". Both of these proverbs have the meaning of asking for something that is impossible, but most Spaniards and Portuguese do not know why they're speaking on elms and pears. The proverbs origin most likely is found in the Sententiae of Publius Syrus (1st century BC), who writes: "Pirum, non ulmum accedas, si cupias pira", "you should go to a pear-tree for pears, not to an elm". The ancient Romans understood it easier: the elm was the favorite "husband" of the vine, so he certainly could not give pears but grapes.

If the Spaniards abandoned the "married" vine in their motherland, they took it to the New World during the Conquista (the Spanish colonization of the Americas) with other forms of tall vine-training systems. They needed wine for Mass, so they planted vineyards wherever they went. They also had succeeded in Bolivia, in the Cinti valley, at an altitude of 1900-2550 meters above sea level, where it was really difficult for growing vines. Yet they solved the problem by "dusting off" ancient Roman knowledge, with vines married to indigenous trees, even very tall ones, the only way to preserve shoots and grapes in that so difficult climate.

If you want to see a "married" vine, come at Guado al Melo estate and visit our little ancient vineyards.

(...continued..)

Bibliography:

Paolo Braconi, "Vinea nostra. La via romana alla viticoltura".

Paolo Braconi, "Catone e la viticoltura intensiva".

Paolo Braconi, "In vineis arbustisque. Il concetto di vigneto in epoca Romana.

Paolo Braconi, "L'albero della vite: riflessioni su un matrimonio interrotto".

P. Fuentes-Utrilla et al., "The historical relationship of elms and vines", Invest. Agrar.: Sist. Recur For (2004) 13 (1), 7-15

Attilio Scienza, "Quando le cattedrali erano bianche", Quaderni monotematici della rivista mantovagricoltura, il Grappello Ruberti nella storia della viticoltura mantovana.

Attilio Scienza et al., Atti del Convegno "Origini della viticoltura", 2010.

Luigi Manzi "La viticoltura e l'enologia presso i Romani", 1883.

Dalmasso e Marescalchi, “Storia della vite e del vino in Italia", 1931-1933-1937.

Emilio Sereni, "Storia del paesaggio agrario italiano", 1961.

Enrico Guagnini, "Il vino nella storia", 1981.

Hugh Johnson, “The Story of Wine”, 1991.

Valerio Merlo, "Contadini perfetti e cittadini agricoltori nel pensiero antico", Alce Nero.

Roger Dion, "Histoire de la vigne et du vin en France, des origines au XIX siècle", Parigi, 1959.

https://fr.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hautain

Guado al Melo News 2019

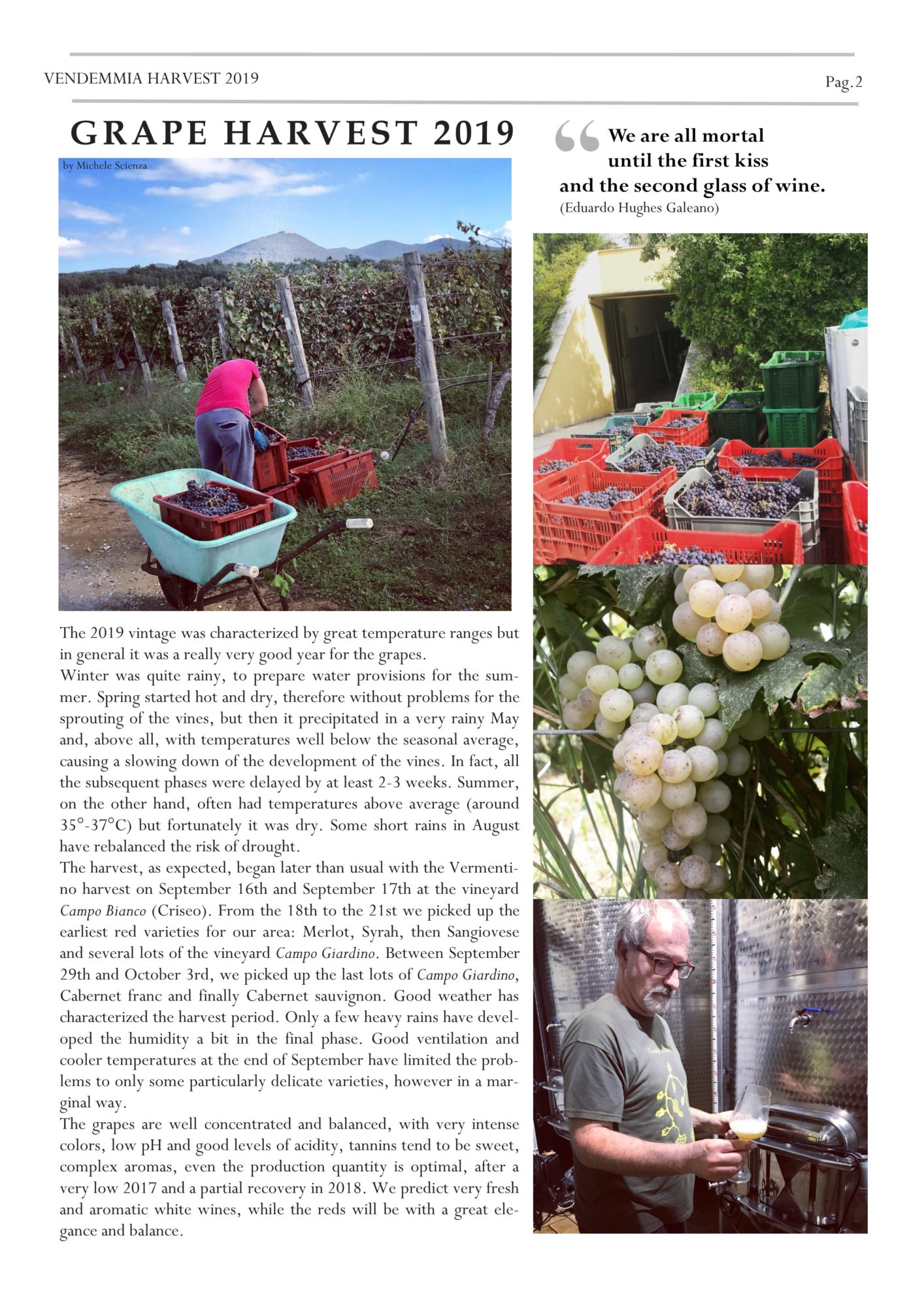

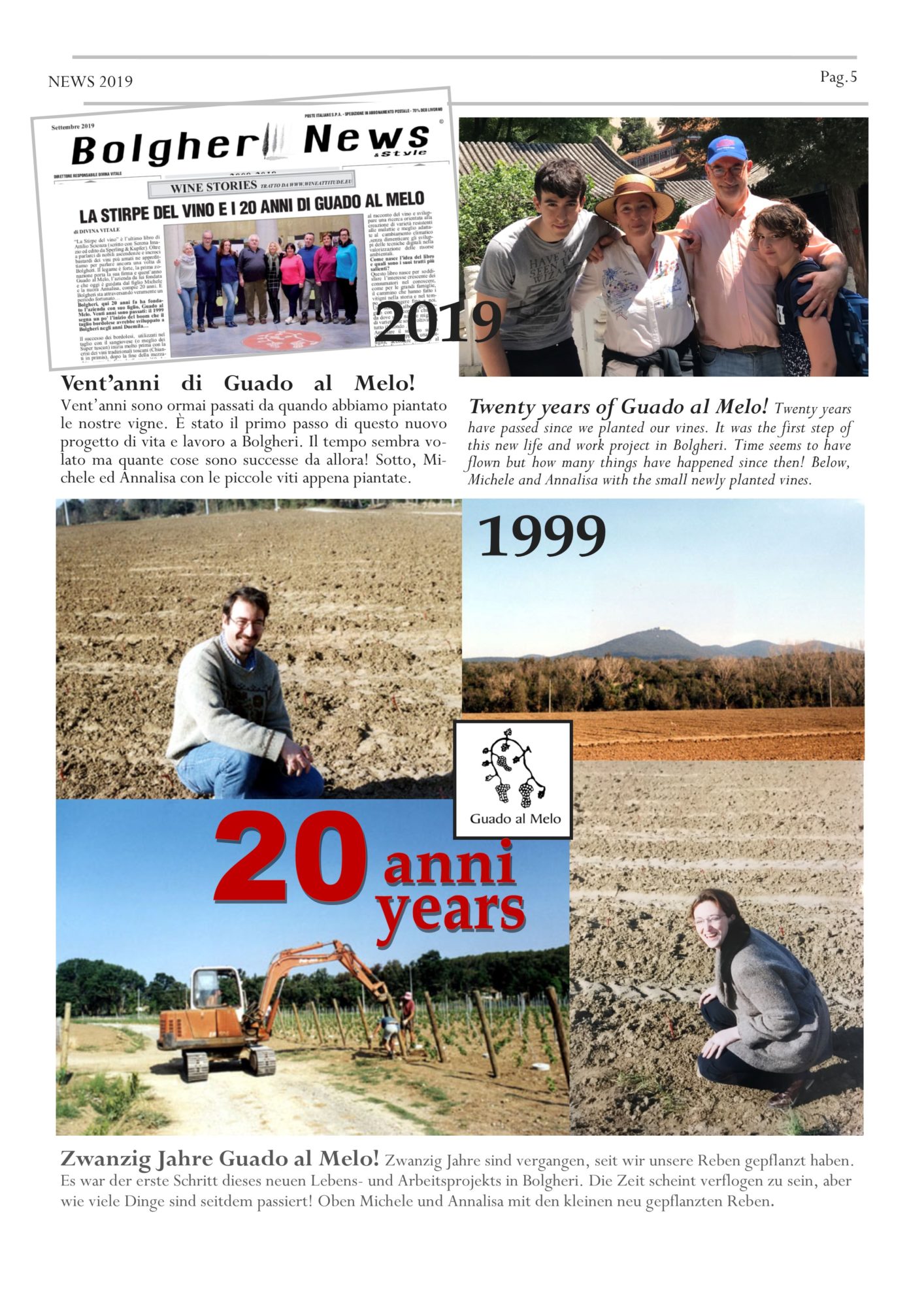

As our tradition, we remember the 2019 (that is ending) with a small publication, with 3 languages (Italian, English and German).

It starts with the harvest, the crucial year moment for us, but then traces the main events and some news for the new year.

This year's quote is from Edoardo Hughes Galeano, Uruguayan journalist and writer, one of the major personalities of contemporary Latin American culture, who died in 2015. We liked it because it underlines, with subtle irony, that it is essentially the function of wine, since time immemorial: giving joy to our days, making us forget the worries of life, as well as love.

Here you can also find it in pdf format.

The taste of wine in ancient Roman times

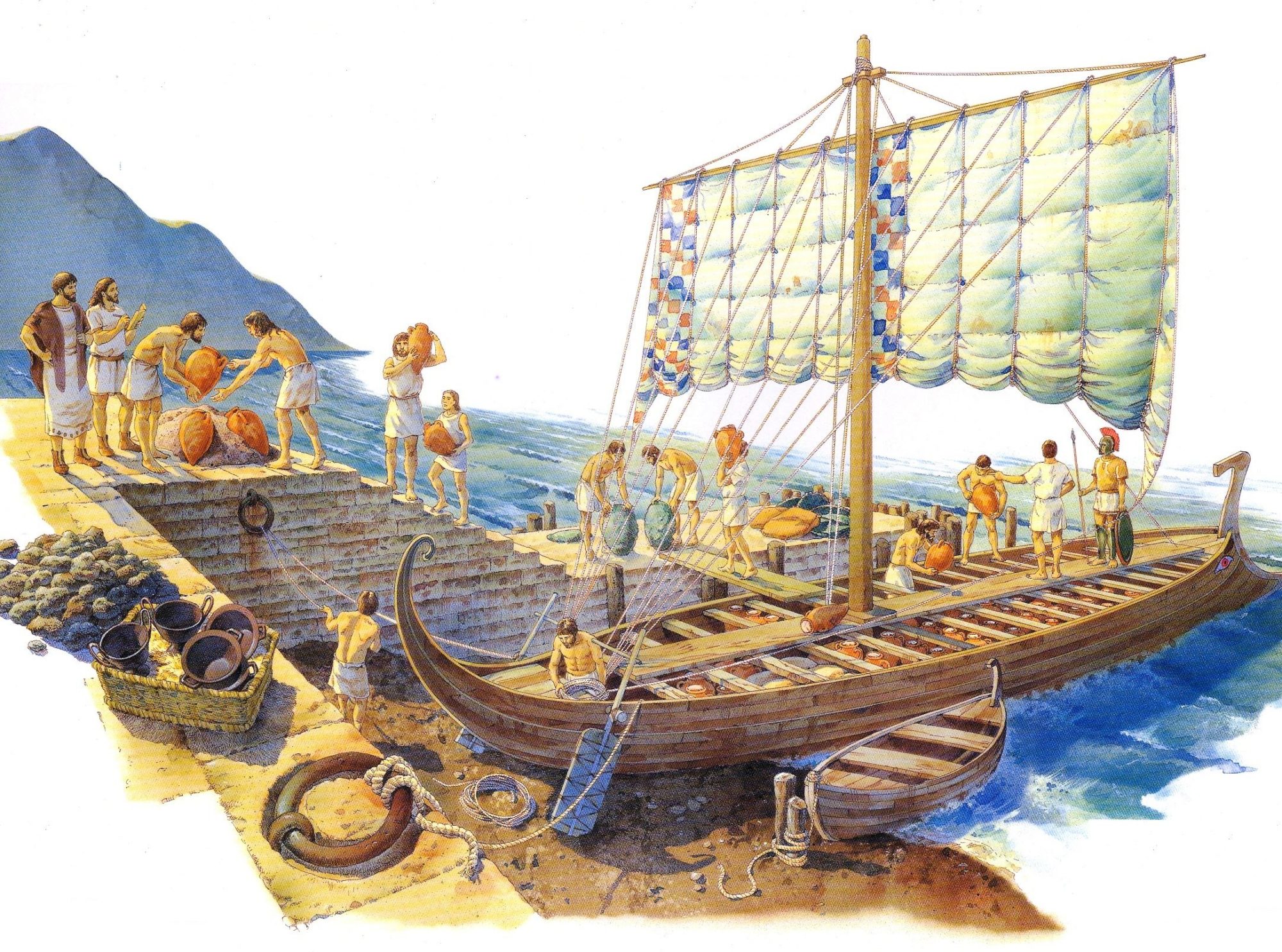

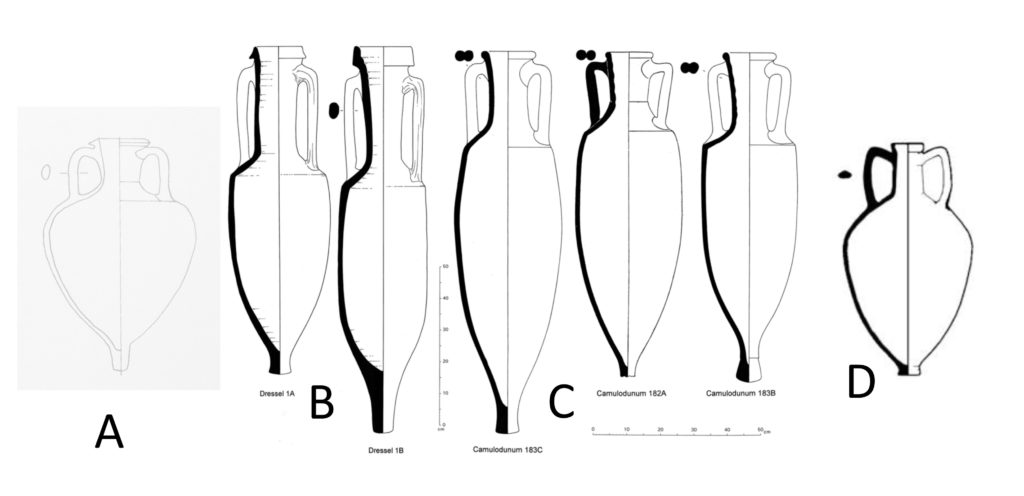

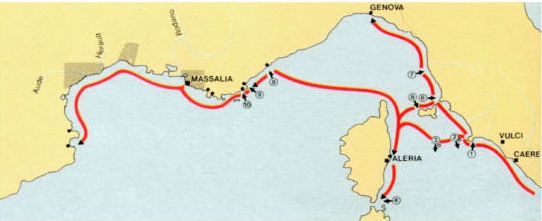

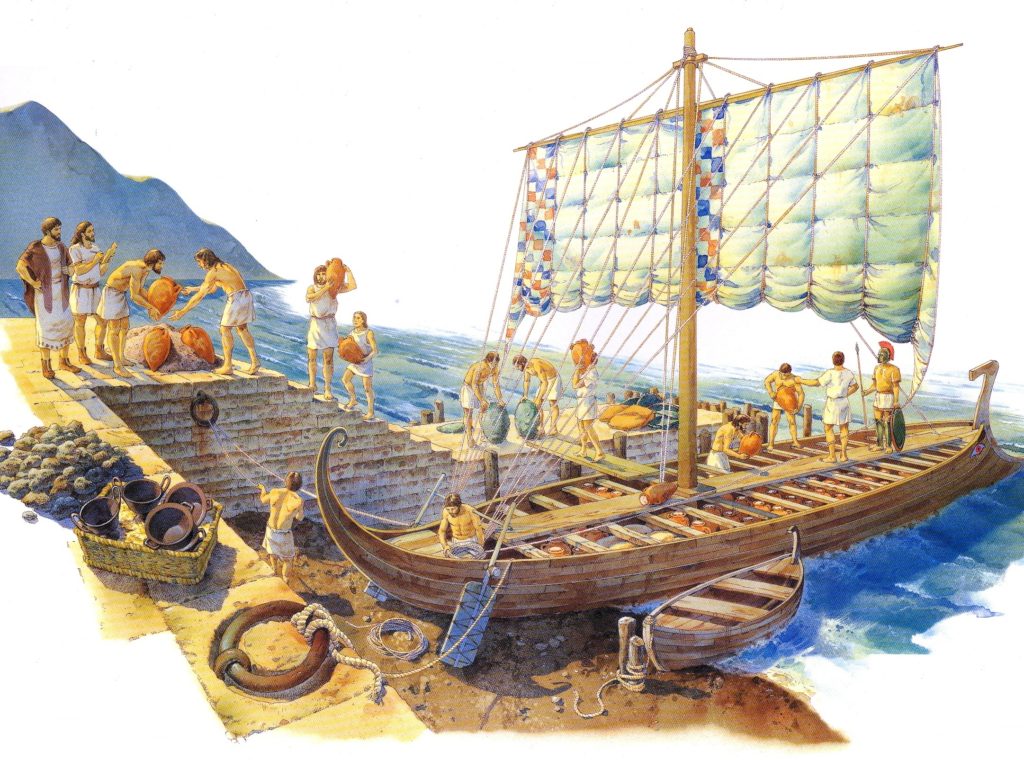

So far, I have spoken about the Roman era in our territory (here and here), about its wine production and European trade.

But, how was this wine?

How can we imagine the taste of Roman wines today?

First of all, let us remember that the Roman period was very long and with great changes. The wines of archaic Rome were certainly very similar to those of ancient Greece and the Etruscans. In those remote eras, limited production techniques produced wines with a "difficult" taste, the consumption of which always required the addition of spices, aromas, honey and so on (see here).

In Rome, however, there was a remarkable agronomic and technical evolution over the centuries, reaching a very different production situation, which we will try to understand.

[one_third][info_box title="The Rural Latin writers" image="" animate=""]

There are five fundamental works to learn about Ancient Roman viticulture and wine production, whose authors were called in the past the Rustici Latini (rustic, or rural, because they wrote about agriculture). These are Cato, Varro, Columella, Pliny and Palladius, which I will often quote in my next posts about Roman wine production.

Each of their works "photographs" a different historical moment in the long evolution of Roman agriculture (about thirteen centuries, for the Western Empire). Understanding a culture, an era, cannot be separated from its becoming, as rightly always Emilio Sereni pointed out: the agricultural landscape is not static but extremely subjected to a perennial historical elaboration.

Less specific aids, more sporadic but no less interesting, come from other non-sectoral authors. These are historians, geographers, poets, etc., such as Strabo, Galen, Cicero, Virgil, Horace and many others.

Unfortunately, we also know that only a minimal part of ancient literature has arrived. For example, Varro, in the introduction to his De re rustica, lists fifty agronomic works in Greek to which he refers, now lost.