We present our vineyards 1: Campo Bianco

On the occasion of the release of the new 2019 vintage of Criseo Bolgheri DOC Bianco, here is a short video where Michele and I present the vineyard where it is born, Campo Bianco.

As good as we are at winemakers :-), we are by no means big players: get over it and I hope you like the content.

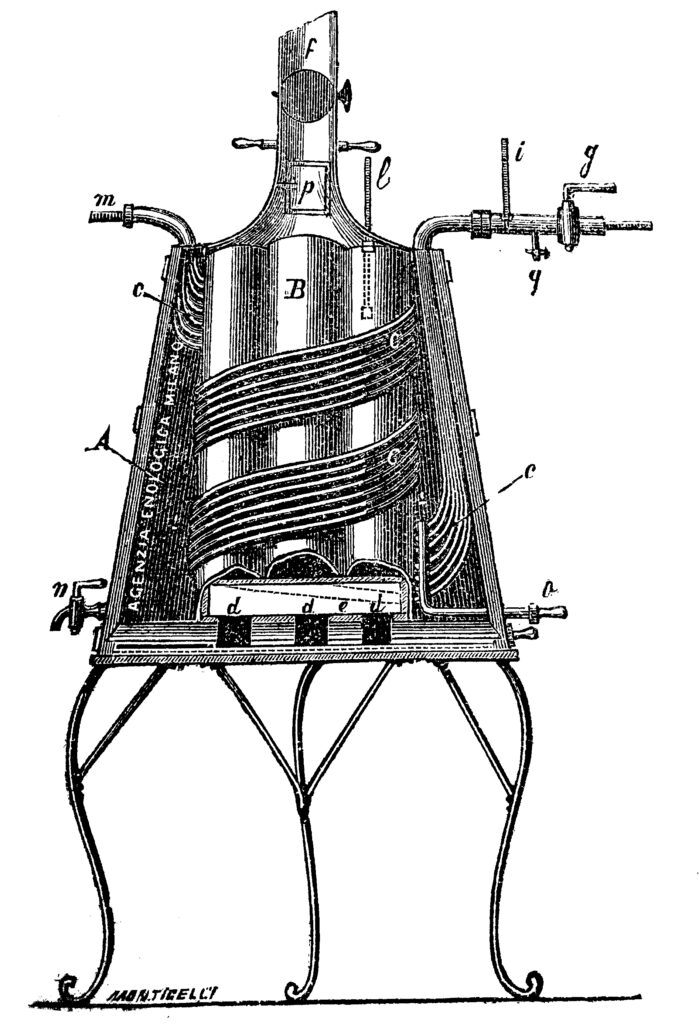

News for our wine museum

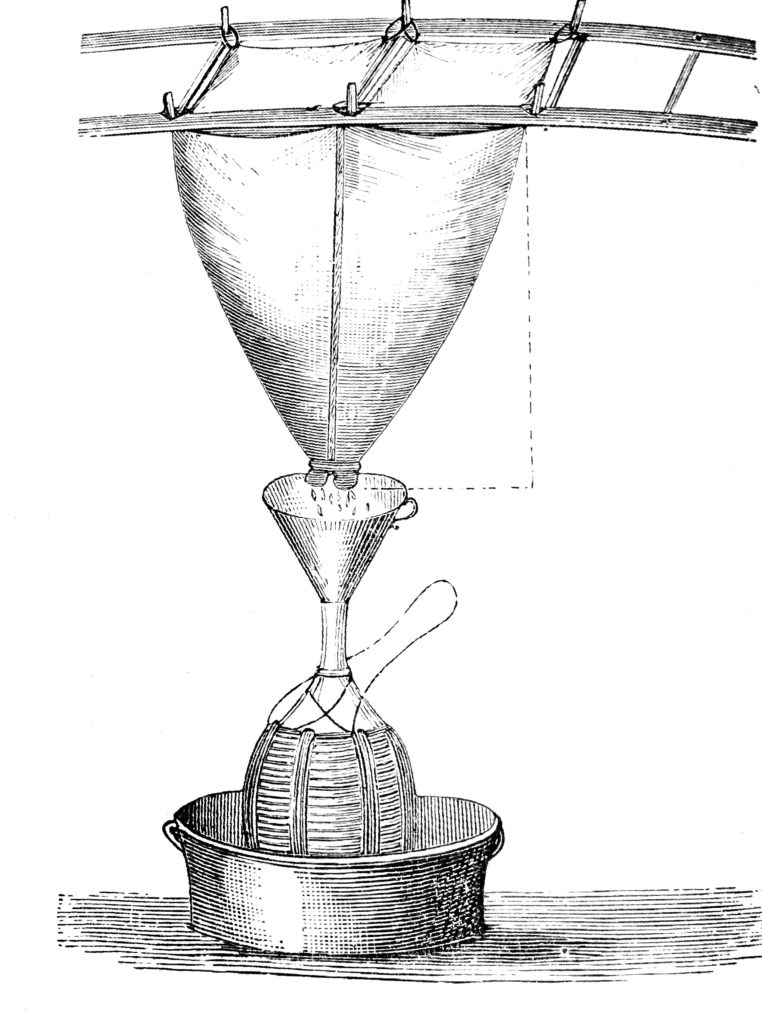

Thanks so much to the great prof. Roberto Miravalle, who donated this beautiful bottler from the early twentieth century to our wine museum.

Our wine museum is open from Monday to Saturday. The summer opening hours, from June 14th, is: 10.00-13.00 16.00-20.00, Saturday afternoon 15.00-18.00 h.

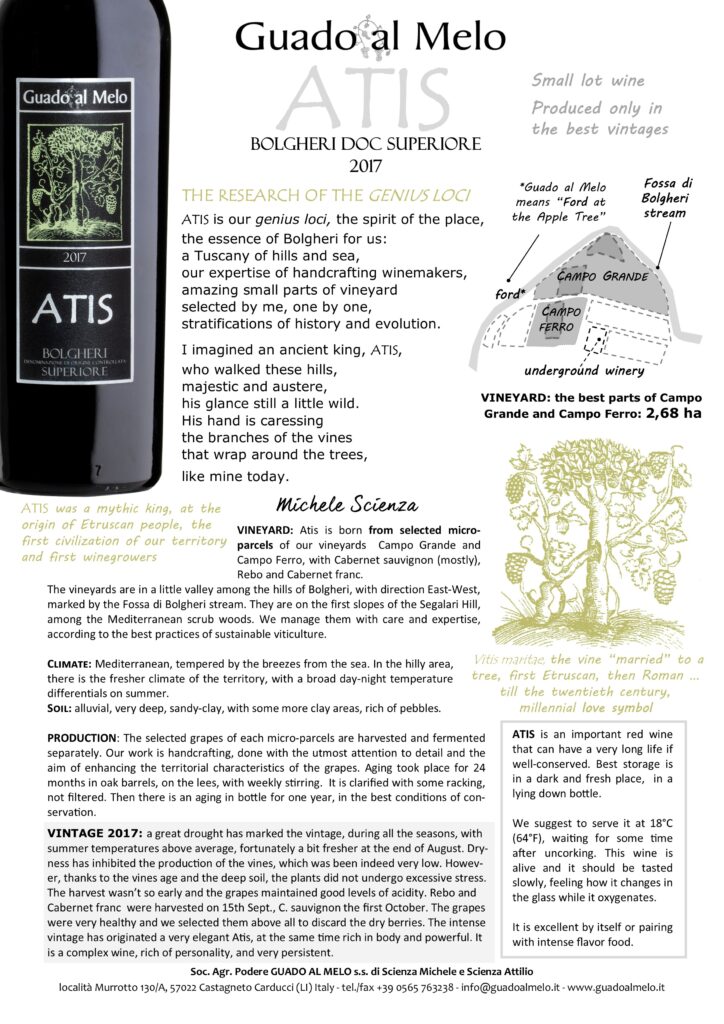

Great news about Atis 2017: more and more personality and sustainability

We kept this surprise so far, but we have been working on it for years. The novelty is that we have made a change in the composition of our Bolgheri DOC Superiore, Atis. The base remains the same, as always, with Cabernet sauvignon (about 80%) and a little of Cabernet franc (about 10%). However, we have replaced the Merlot (the last 10%) with the Italian variety Rebo. Don't worry: it's not a drastic change, as you will see. The advantage is that it leads us to an Atis with an even more pronounced and harmonious personality, as well as more sustainable.

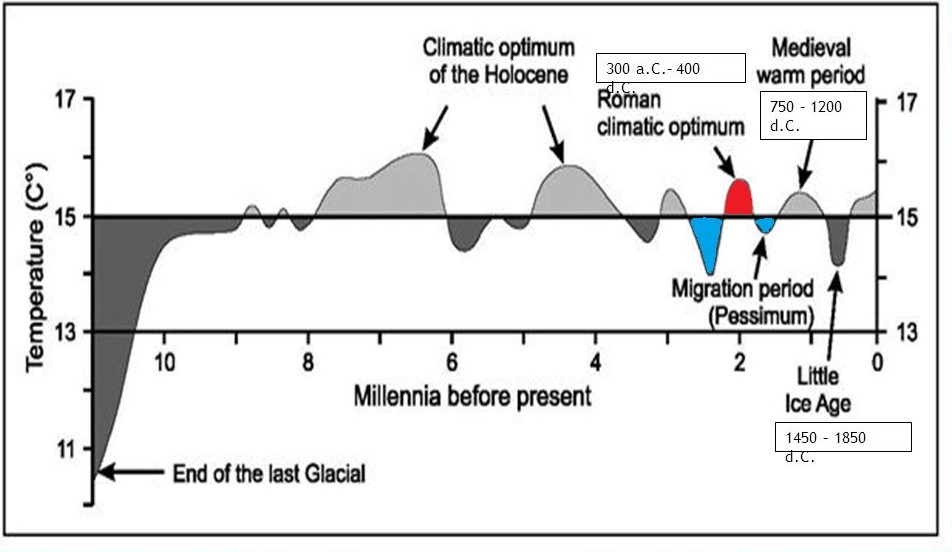

The main reason of this choice is the climate change. Rebo filled us with great satisfaction in its relationship with our territory for years during our constant and multiple experiments. Conversely, Merlot left us a little perplexed, especially in the recent years. The climate change made it increasingly difficult for us to find the perfect moment of its harvest for the production of the Bolgheri Superiore wine. This moment was carried forward more and more to compensate for an imbalance between the maturation of sugars and acidity with the polyphenolic one.

The change is not so drastic also because the Rebo is a variety resulting from the crossbred between Merlot and the Italian variety Teroldego. It was born in a program of crossbreds to improve the quality and resistance of the varieties, that began in the 1920s at the research center of San Michele all’Adige. The name derives from its creator, the geneticist and agronomist Rebo Rigotti.

What are the advantages of Rebo?

It is an optimal variety for sustainability because it has very good resistance to grapevine diseases and weather adversities. It has excellent characteristics of both quality and production regularity. Its maturation is later than Merlot, which makes it much more suitable for optimal ripening in our climatic conditions. However, it maintains the original aromas and taste of Merlot in the wine, but with more freshness. This contribute to much more balance to an important wine, which is born in a Mediterranean area like ours.

Taste it and tell us what you think.

Below is the wine card and the awards it has had so far. Here you can download the data sheet in PDF version.

Let's defend the real wine: whether it is watered down, de-alcoholised, manipulated ... please don't call it wine!

Alarming news has begun to circulate in the press and on the web that Europe can admit the watering down of wine. Then, there are those who wrote that it is fake news.

However, there seems certainly that there is a discussion in Brussels about the regulation of partially or completely de-alcoholised wines, whether they are obtained with the addition of water or with other systems.

Behind that, there is the expanding marketplace of wines with low alcohol content (or totally free of alcohol). All revolves around the crucial question: are these drinks wine? Or rather, will they be able to boast this important indication on the label? Here everything is at stake: if they will be able to write wine on the label, it will be decisive for the future market of these products, but … I hope not.

On the one hand, there are politicians from northern Europe, with a prohibitionist approach, who want to limit the consumption of alcohol, pushing towards de-alcoholic products. One wonders, rhetorically, why the main target of these politicians is always wine, produced in the Mediterranean countries and central Europe, and not the huge multinationals of spirits (with a lot of money and a lot of ability to advertise, as well as than to impose themselves politically). In fact, I think that people that abuse of alchool don't exceed with Bolgheri or Barolo or Lambrusco. I think it happens more frequently with vodka, beer, other spirits or cocktails. However, Europe seems pushing in this direction, using terrorism techniques on our health. They start from even partially correct considerations, which are however communicated in an extreme way, in an increasingly paternalistic vision of power.

On the other hand, there are those who see enormous opportunities for the sale of de-alcoholised wines in Muslim countries, where the consumption of alcohol is formally prohibited (even if it is often used privately), or in markets where wine still fails to enter.

Politics will therefore decide what to write on the label, but is de-alcoholised wine real wine?

I think not. Wine is a millenary drink, that is the result of the transformation of grapes, of a land and its culture, of a meticulous and respectful work in the vineyard and in the cellar. Those who believe in artisanal wine, in its inseparable link with the territory and nature, doens't see kinship with these products. Call them what you like, but not wine.

Michele remembers in the 1980s, when he was still studying at the agricultural institute of San Michele, a similar story with regard to "wine coolers". At the time, always with the idea of capturing consumers from countries not accustomed to wine or the younger generations, the production of wines with added fruit juices (like ready-made cocktails), called "wine cooler", seemed to be tempting. What happend to them? Forgotten and without success (thankfully). I don't demonize them, but all of this has little to do with real wine. These are attempts to sell low-quality wines, which are otherwise difficult to sell, manipulating them in the most diverse ways. They are, in fact, different drinks: let's not ruin the real wine by confusing it with them.

Some, in Italy, positively judge these de-alcoholization techniques, with the aim of lowering the gradations of wines which are always higher. I state that I do not share too generalized discourses on what is pleasant or not in wine taking into consideration only a single element. There are 12-13 degree wines that are unbalanced and heavy. There are wines at 14 degrees, or even more, which are perfectly balanced, with a lot of complexity and also freshness.

The climate change certainly plays an important role in this regard. However, remember that the alcoholic strengths began to rise well before, for other reasons as well. A good part of the world of wine has been pushing in this direction for thirty years already, with determined and well-targeted choices of winegrowing and winemaking.

Is it really necessary to use the de-alcoholization to return to having wines that are more drinkable, less heavy and less alcoholic?

Certainly not. Let's not forget that wine is born first of all in the vineyard (and it's not just a cliché). Let's go back, for example, to choosing the most suitable varieties for the territory and not for the market. Let's go back to rethinking the exposure of the vineyards, the training systems, the planting density, the thinning, etc. Whether it is to change wine fashions or to combat climate change, the good viticulture, that is, the skilful care of the vineyard, is the best ways towards more balanced and pleasant wines. These chooses are much more sustainable, as well as able to preserve our culture of wine and the territory.

Wine tours and tasting in April and May 2021

Given the recent government regulations due the virus Covid, in May we can carry out tastings and guided tours with some limitations.

Tastings can only be done outdoors. Given the structure of our winery:

1. Visits and tastings will not be possible in case of rain or strong wind.

2. They can only be done in good weather, but we still have a limited number of places. Therefore, the reservation becomes mandatory in any case.

3. Each reservation can be definitively confirmed only in the previous 2-3 days before the visit, based on the weather forecast.

I also remember that the usual safety rules on distancing remain in force, both during the visit and tasting, except in the case of relatives or cohabitants. There is also the obligation to wear a face mask at all the time of your stay in our winery, except when you are tasting.

We are sorry for these inconveniences. From June, we should be able to return to do the tastings in the cellar, with the appropriate precautions.

Wine Spectator's reviews of our wines

Here there are the reviews of Wine Spectator of our wines. We are very pleased due to the very good ratings and their tempting tasting notes. Read below.

The vine and the spring frost

In these days, there is a lot of concern in the world of wine about damage from spring frost. Imagine the anger and despair of those who see their gems die overnight.

We are in an area (the Mediterranean one) where frosts are more than rare, but you have surely seen the (poetic) photos of fires lit in the vineyards of central Europe, especially in France or Switzerland, to combat damage to the vineyard.

Why does this happen? In this season, a phenomenon of thermal inversion can be created in the lower layers of the atmosphere. At night, the earth releases heat to the air and, at ground level, temperatures can drop even dramatically.

In the areas where the risk of spring frost is very rare, such as the Mediterranean ones, when these events happen, it becomes difficult to take cover.

This phenomenon are frequent in the territories with a continental climate, especially those more northern. In particular, the risk in these areas is greatest in the valley floor and in the plains. The wine producing was (and is) too important and the vineyards have been planted everywhere, even in places that are not exactly perfect for these plants. The winemakers of these territories, who have been fighting against these adversities for thousands of years, have developed useful practices to contain the damage caused by spring frost. Let's see what they are. However today, sometimes, other choices prevail, useful for other purposes, but which expose the vines more to the risk of frost.

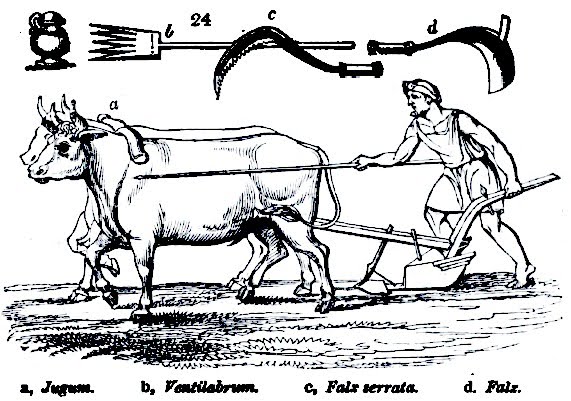

Firstly, they used traditionally varieties characterized by a late bud break. In addition, the winegrowers pruned the vines as late as possible. In fact, the delay in pruning can set back the moment of awakening of the plant. Even the agro-ecological choices can limit the damage caused by frost, such as the presence of grass under the vines or trees and hedges among the vineyards (very common in the past).

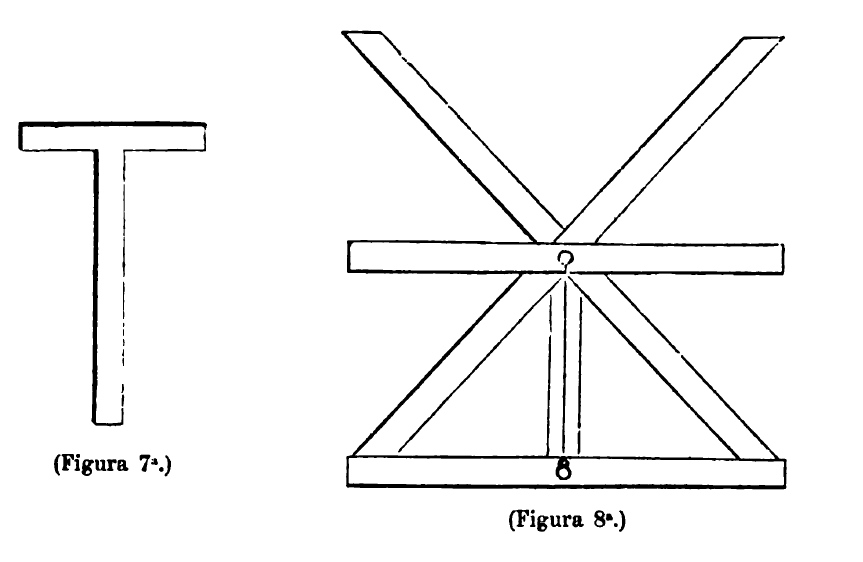

Above all, the high-vine training systems were used traditionally in these territories. In fact, during the spring frost, the coldest layers of air are those closest to the ground, while the temperature rises moving away from it. Going from 0 to 2 meters in height, there can be variations of even 5-10 Celsius degrees. The tall vine training systems (such as the traditional "vine married to a tree", the Casarsa, the Raggi, the Belussi, the pergola, etc.) are perfect systems to avoid, or at least contain, this problem. Today, if you notice it, the lit torches are always in low vineyards.

Fires were lit with sheaves of straw or shoots already in the ancient Roman times, just as today various types of stoves or anti-freeze candles are lit. Another modern system is the anti-frost irrigation, that is, water is sprayed on the vines (as long as there is good water availability). The benefit comes from the fact that the water has a higher temperature than the atmospheric one. In addition, part or all of water can freeze. The transition of the physical state of water from liquid to solid is a phenomenon that releases heat. Finally, even more expensive, there is the system of putting tall fans in the vineyards, which push the warmer air downwards. I believe that the helicopters, that are sometimes seen, has only a "spectacularity" function, because they pass by day, while the phenomenon of thermal inversion is nocturnal.

However, all these systems are not sustainable, because they consume resources and emit high levels of Co2 into the atmosphere. They can be useful if used occasionally. If the use of them were to become frequent enough, perhaps something is wrong about the location of the vineyard, the choices of the training systems, the varieties, …

Sustainability comes first of all from excellent knowledge of the best viticultural practices for the type of territory. However, there is always a certain degree of unpredictability in the work of the winemaker. As capable as we may be, we are always subjected to the vagaries of the weather and luck.

L'Airone 2019: 91 point from Wine Enthusiast

Our little egret (Airone), with my beloved Vermentino, gives a beating of wing at the end: it collects 91 points from Kerin O’Keefe, on Wine Enthusiast, a score that is usually achieved by wines of a much higher price range.

Our little-big Airone, however, does not flatter itself, it only confirms how in Bolgheri fine white wines can be born, even among the youngest ones. Have you tasted it? Did you like it? Tell me your impressions. I really love its delicately soft lightness and its iridescent scents.

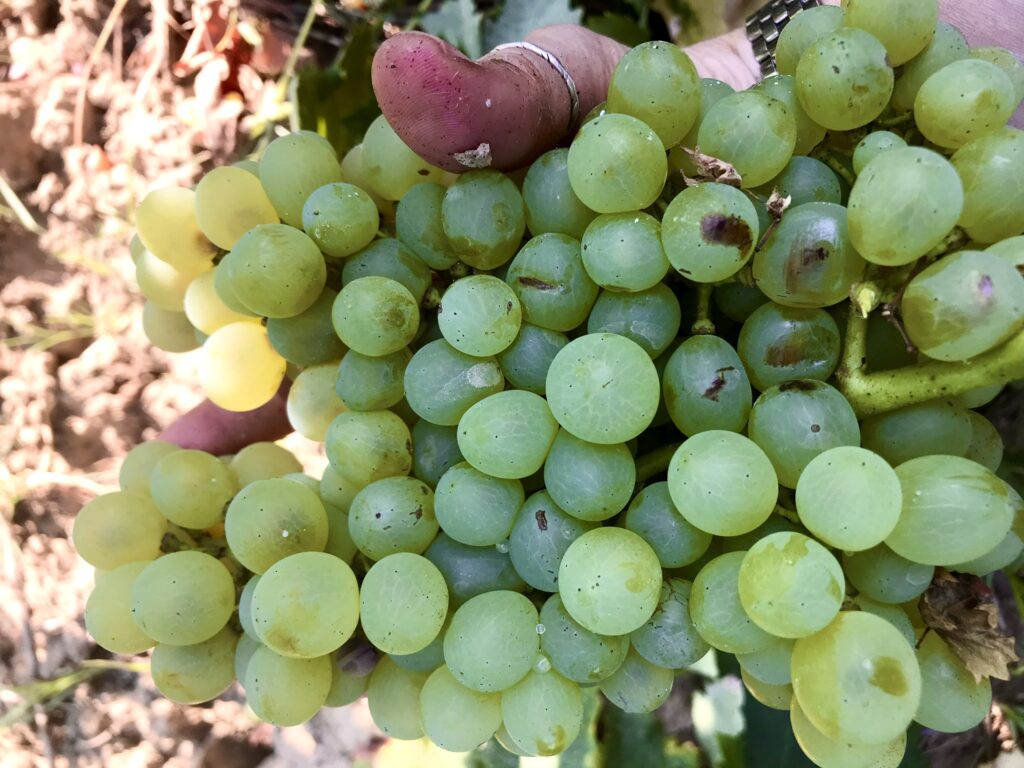

Vermentino, as we know, loves the sea: it is the white grape of the Tyrrhenian coasts par excellence. It is a variety that makes happy the winegrowers in the vineyard (it adapts to even very difficult conditions, giving us beautiful clusters of large sun-colored berries, often slightly pink). However, it tests the mastery of the winemaker in the cellar (already finding the perfect moment of the harvest requires a lot of attention). However, if we approach him with love and respect, he give us a wine with a very marked personality.

I wrote "a beating of wing at the end" because there are few bottles by now in the cellar. There will be soon the new 2020 vintage. It is the usual problem of managing reviews for the young wines. At the time of tasting by the journalists, the new vintage is not ready. By the time the tastings are concluded and the results are published, the wine is almost finished.

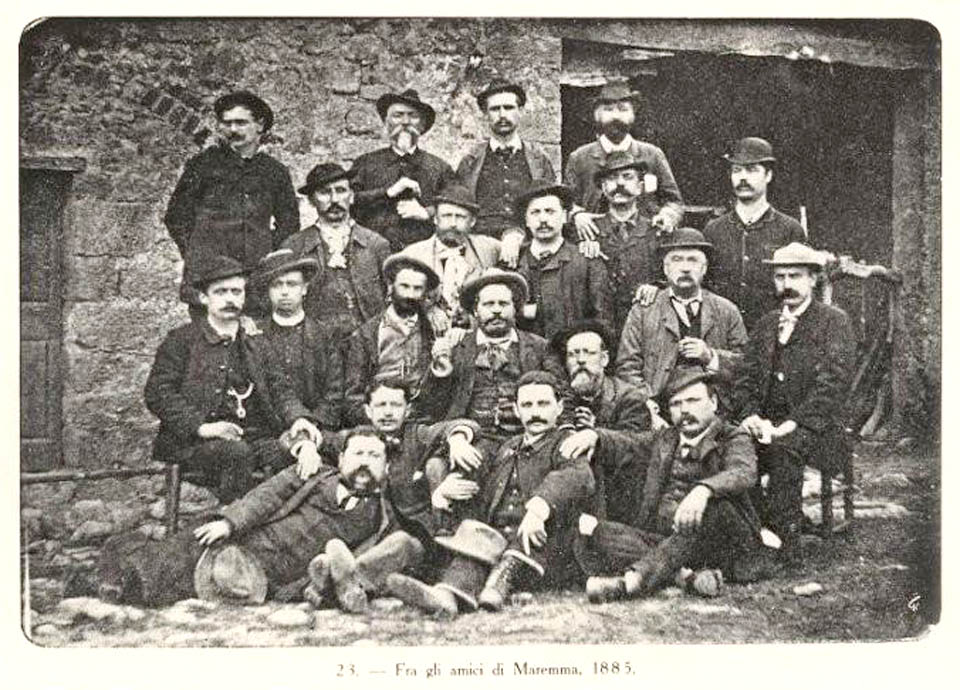

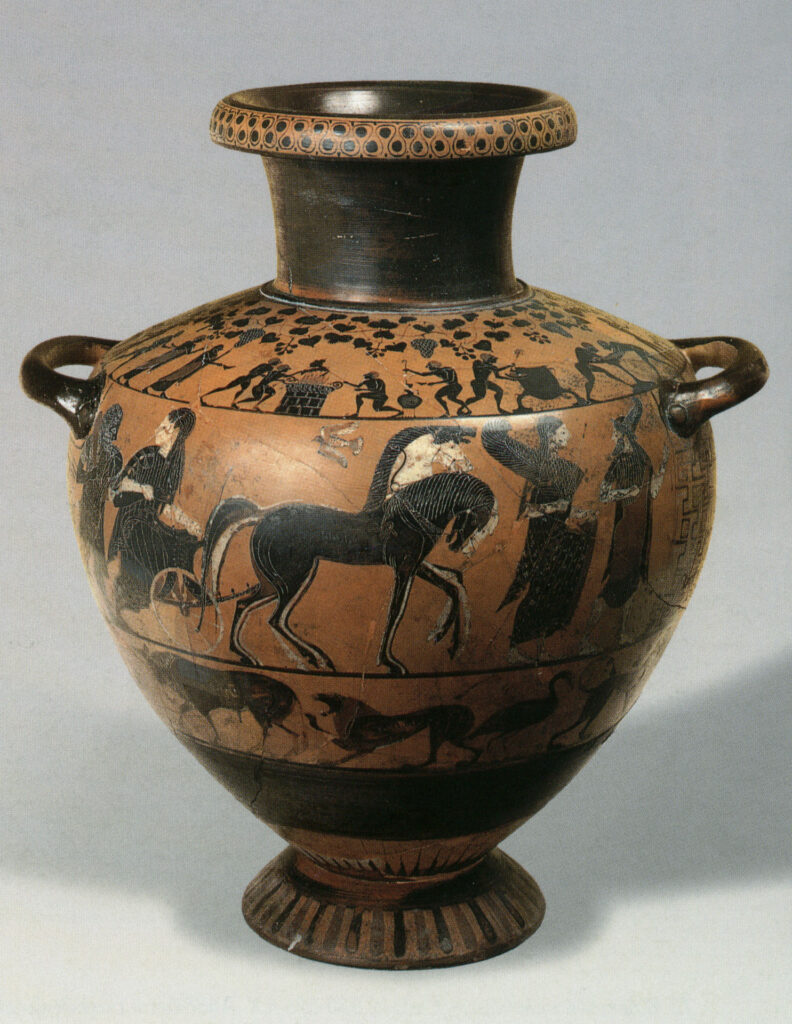

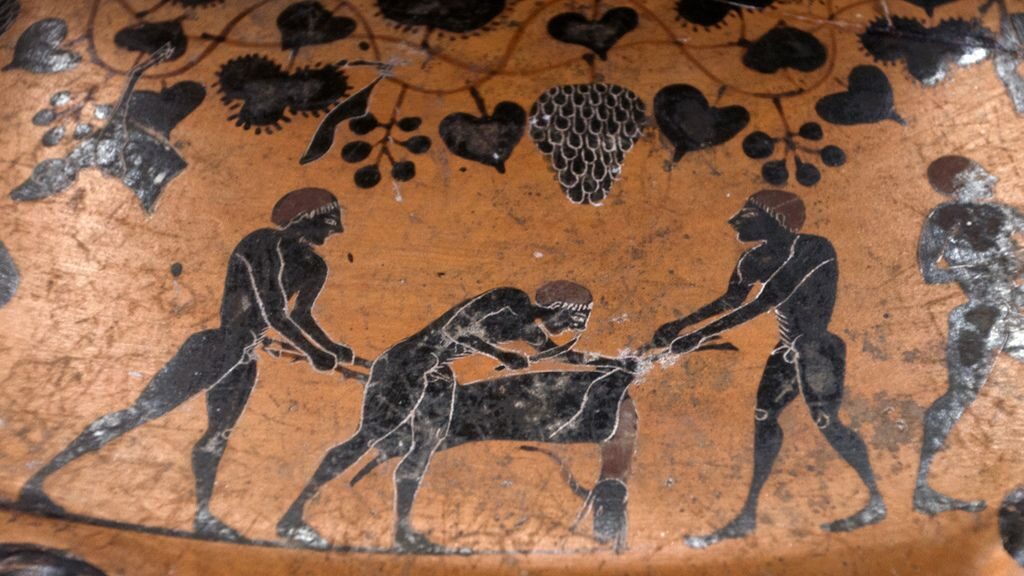

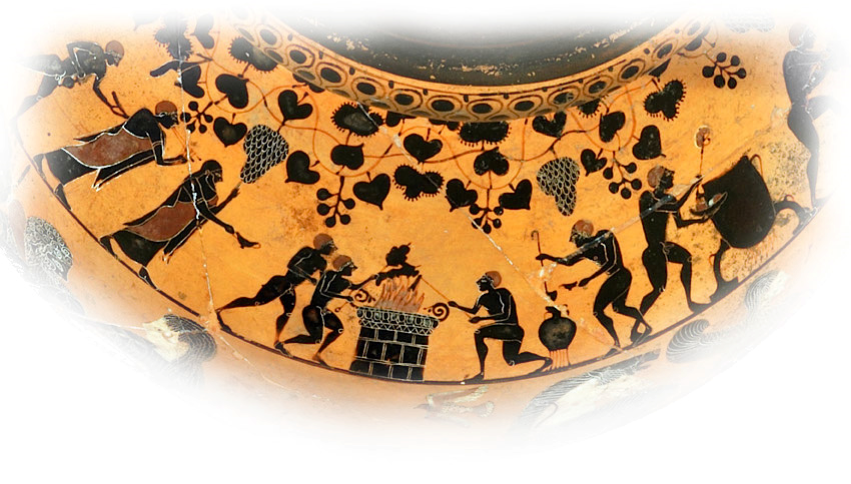

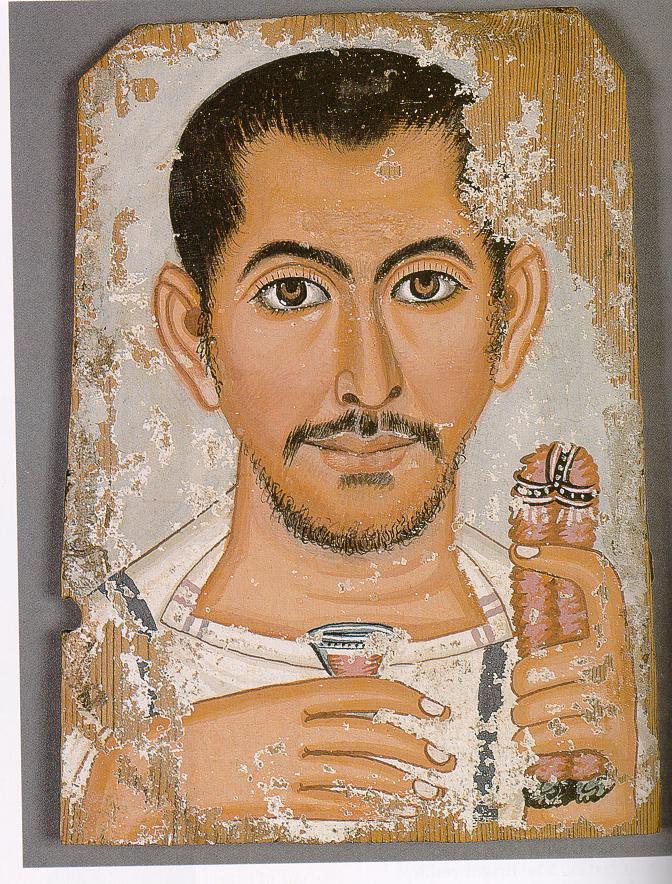

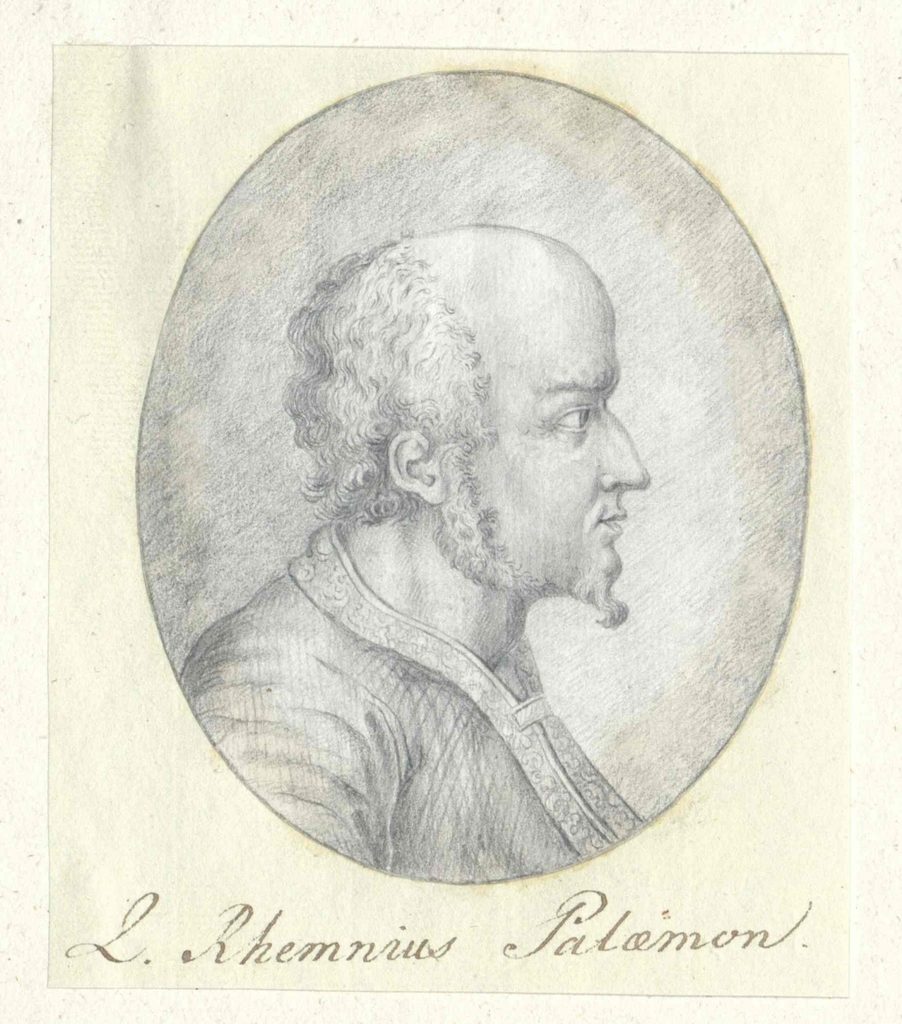

The great wine boom in Bolgheri: the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries

“I have been in Maremma for a long time. There is not even a wolf anymore. Where those poor animals came in droves in the evening, howling, now yellow vines bloom and the boys play the mandolin. The old secular oaks were cut down, years have passed, and everywhere there are olive trees, wheat and vegetable gardens. You can see the dark green of the woods only in the high hills; and some old boar, bored by the world, retires there … No more buffaloes. It's a sin. Something is missing.

But the wine is a lot and it is very good!”.

This is a letter that the poet Giosuè Carducci wrote on October 26 1894, telling about one of his trips to Castagneto and Bolgheri, the lands of his childhood. In these few lines, he makes a perfect synthesis of the change in the territory that took place during the nineteenth century: from a wild area, it has become an agricultural one, where a very good wine is produced. Are you ready to find out it?

Windy vineyards, Carducci and Barbaric Odes: as Paolo Conte sings (in Italian and Spanish) in "Cuanta Passion":

"… Le vigne stanno immobili / nel vento forsennato / Il luogo sembra arido / e a gerbido lasciato / Ma il vino spara fulmini / e barbariche orazioni / che fan sentire il gusto / delle alte perfezioni …. (The vines stand still / in the frenzied wind / The place seems arid / and uncultivated / But the wine shoots lightning / and barbaric prayers / that make you feel the taste / of high perfections ...)

Cuanta pasiòn en la vida / Cuanta pasiòn / Es una historia infinita / Cuanta pasiòn / Una illusiòn temeraria / Un indiscreto final / Ay, que vision pasionaria / Trascendental! … (How much passion in life / How much passion / It is an infinite story / How much passion / A reckless illusion / An indiscreet ending / Oh, what a passionate vision / Transcendental!)

(Paolo Conte, "Cuanta Passion")

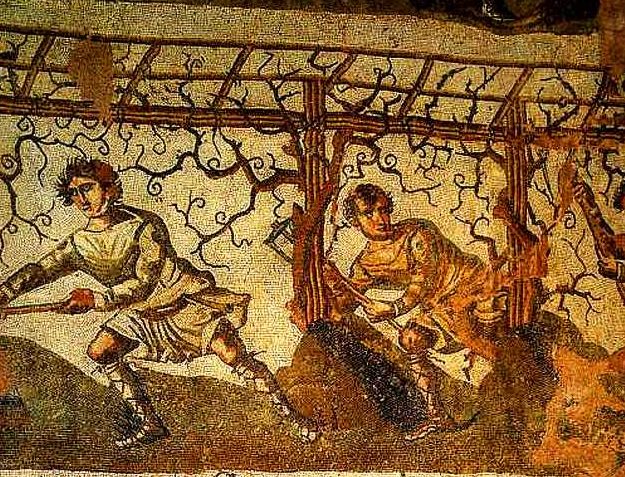

We are continuing our journey in the lesser known history of the Bolgheri DOC, our small Tuscan wine appellation, located in the municipality of Castagneto Carducci (Carducci, in honor of the poet, of course). We have already seen how here, in Etruscan land, the viticulture was born in an autochthonous way, starting from the wild vines of the woods made domestic (here). We learned about the traditional Italian training form of the vine "married" to the tree, born in the Etruscan-Roman culture and never disappeared until about the mid-twentieth century (here and here). We have seen how, especially in Roman times, ours was a flourishing agricultural territory, wine producer, at the center of a network of European trades (here and here). We have seen how a difficult phase followed (here), when the Maremma becoming harsh and wild, but the wine resisted, even if only for subsistence.

The nineteenth century was the century of the rebirth of our area. The territory returned to having a flourishing agriculture, completing the transformation slowly begun in the previous centuries. Above all, the wine production increased, as I'm going to tell you.

The transformation took place thanks to the reclamation works begun at the end of the eighteenth century. The Maremma, from a forgotten and exploited land, had now become the “great sick” to be healed in the Grand Duchy of Tuscany, thanks to the new sensitivity born in the Century of Enlightenment. The definition of Maremma at the time was not strictly geographical, but socio-economic. It included all those territories of Tuscany characterized by "little agriculture, massive extension of woods and marshes, scarce population" (Carlo Martelli, 1846). Our part of Maremma, called at the time "Pisana" (of Pisa; the current province of Livorno will be established in 1925) was the first to complete the transformation and move up a category.

The disparity between the different parts of Tuscany was enormous and the common thought about Maremma was divided between compassion and contempt. For example, the French agronomist Drédéric Lullin de Châteauvieux, who visited our lands in 1834, wrote that he felt like "sur la frontière du désert au de-la toute culture cesse" ("on the frontier of the desert beyond which the culture ends”). Beyon this border, extreme poverty, malaria and bandits continued to reign.

If this was the opinion of the time, you will understand why leaving the category of Maremma was seen as a victory, as evidenced by the politician Alfredo Beccarini in 1873. He wrote that the Maremma begins under San Vincenzo, as the northernmost territories were already reclaimed and occupied by farmers, to the point now "to despise the ancient and defamed name".

The exodus from the hills

Before telling about wine, let's see how the landscape of Bolgheri territory has transformed in general in this period. Between the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, the actual structure begins to take shape, with the definitive shift of the focal point from the hills to the coastal flat.

The agricultural development therefore started from the hills and the foothill areas. The deforestation then extended to the plain area around Bolgheri. Then, it advanced in the rest of the plain, which began to be populated, in parallel with the water regulation works, which eliminated the marshy areas.

The occupation of the plain also required the creation of a better road system. At the beginning of the nineteenth century, the via Aurelia was rebuilt, the ancient Roman consular road, by now plundered by stones and reduced to a path (or a little more). The new road was realized some meters towards the sea than the original route. The famous boulevard of Bolgheri, created in the late eighteenth century, was planted in 1831 with poplars. These trees were replanted several times because they were constantly damaged by the (last) buffaloes. In 1834, they began to be replaced with the cypresses, not so good for the buffaloes. At the time of child Carducci, who then made the cypress avenue famous with his nostalgic ode "Before San Guido", the trees arrived halfway along the route. The tree-lined avenue was completed till Bolgheri after the poet's death (1907), to pay homage to him and his famous ode.

The rall straigh cypresses in double row

troop from San Guido down to Bolgheri;

like giant striplings at a race they go

Bounding to meet and gaze once more me.

Straightway they knew me: "Welcome back again,"

Bending their heads to me they whispering say,

"Why dost thou not alight? Why not remain?

The evening's coll, familiar the way,

"Oh, sit thee down beneath our odorous shade,

Where breathes the North-West wind from off the sea.

...

I have found the traslation here.

...

The definitive shift of the population towards the plain depended by the construction of the railway line, in 1863. The station was built next to a farm belonging to the della Gherardesca noble family. Around it will develop what is now the most populous village of the municipality, Donoratico. It takes its name from the ancient hilltop fortress (that I have already mentioned), abandoned for centuries.

While the foothills and the plain were being deforested, the forest returned to regain most of the hills, especially due to the abandonment of the pastures. In general, the colonization of the plain will have the effect of a real exodus of the population, who will increasingly abandon the hills to move towards the plain. The great extension of the hilly woods, that we can still see today derives, for the most part, from natural reforestation phenomena, which occurred in the last hundred / one hundred and fifty years.

The wood widened but at the same time it ended its ancestral relationship with the local people. For millennia, it had been at the center of a large part of the local economy and life, with the harvesting of chestnuts and much more. It was populated by charcoal burners, woodcutters, gatherers, pigs that grazed in the wild. Today it is a wild and empty forest, if not for the shooting of hunters and companies specializing in cutting wood.

The deforestation of the plain caused deleterious effects on the environment. Thus, in 1837, the planting of the coastal pine forest began, above all to act as a barrier to the wind and sand, to protect the cultivated fields. The railway made transport by sea disappear and thus permanently closed the Customs offices, located in the ancient fort on the beach (on the far right in the photo below). Close to it, in the 20s of the twentieth century, the first small group of villas was born in what would later become the seaside resort of Marina di Castagneto.

The great expansion of the wine, between tradition and modernity

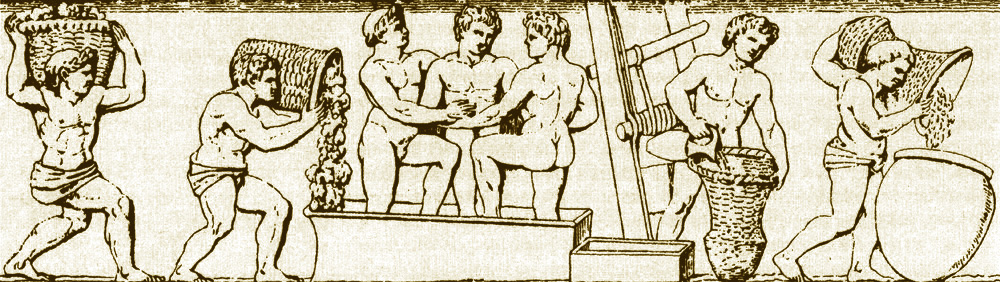

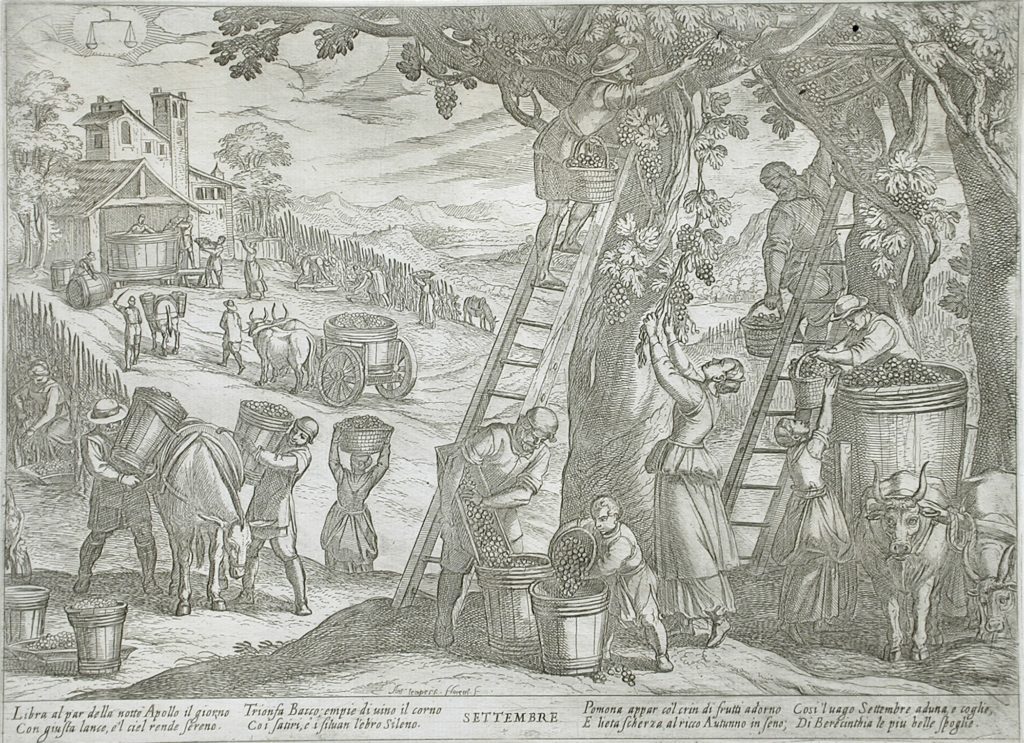

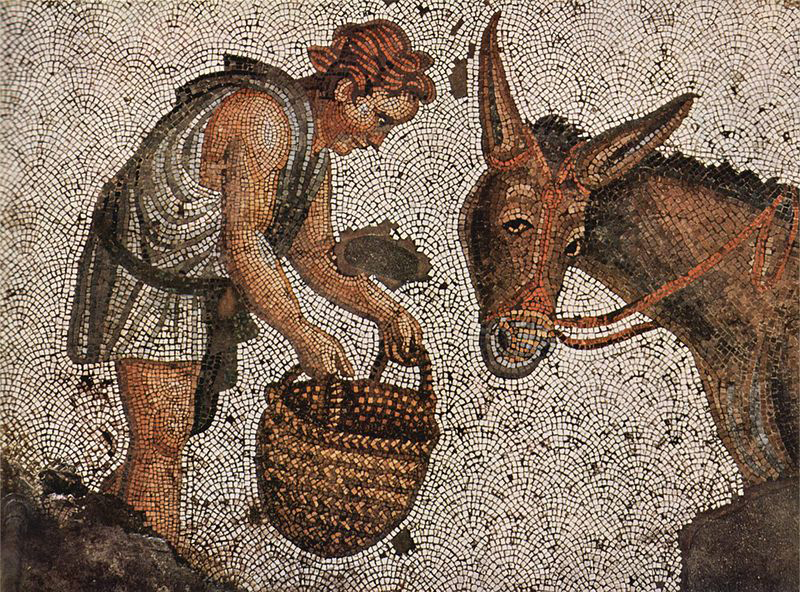

On the nineteenth century, there was a fairly generalized boom in wine production throughout Italy (and in the rest of Europe). The production grew almost everywhere, driven by the significant increase in the population at the time, as well as by the progressive improvement of production techniques. The same happened in our Maremma Pisana, as told in the Tuscan Agricultural Journal of 1832, in the article "Corsa Agraria della Maremma" ("The rapid increase of agriculture of Maremma") (here the full article):

"The main income items of a possession in Maremma are: 1 ° the cereals, 2 ° the wine, 3 ° the oil, 4 ° the cattle, 5 ° the woods. …

The cultivation of the vine spreads for every where in Maremma … "

As reported in the piece, the vineyards in Maremma increased a lot because the wine production was no longer able to fully satisfy the local request. The wines were already sold out before the summer. The article highlights the strengths and weaknesses of this production, more or less the usual problems of the time: the production of too many quantity of grapes, bad oenological techniques, especially that so called Tuscan "governo", wine-cellars not suitable for the storage (especially for the temperature).

What is the Tuscan "governo"? How was the wine producted in Tuscany at the time? The "governo" was a winemaking practice useful to give more strength to poor and too light wines. They were frequent at the time, due to limited winegrowing and winemaking practices . It was not the only system: for example, it was common at the times to reinforce weak wines by adding a little grappa or other liqueurs, both in Italy and in France. Firstly, some healthy bunches were harvested separately, which would be used for the "governo". These bunches were dried on racks or hung on hooks and wires in the cellar. The rest of the grapes were normally harvested and winemaked. Then, the wines were placed in wooden barrels. On November, the chosen bunches, now partially dried, were pressed and the fermentation was started. The "governo" was this mixture of very concentrate fermenting must and skins that the winemakers added to the casks (not completely filled at first) of the weaker wines (from 5 to 10%). The (relatively) low temperature of the period, the alcohol present and the little sugar caused a very slow fermentation, which lasted even a month. This practice enriched the wine with few degrees of alcohol and a some more scents. This wine was slightly sparkling, due to the carbon dioxide developed in the second fermentation. The "governo" wine was consumed young, leaked directly from the barrel.

The Tuscan Agrarian Journal is critical about this practice. Firstly, the producers often neglected the good care of the production due to the possibility to correct the wines with the "governo" practice. Secondly, the "governo" reinforced the wine but also originated several defects. The refermentation, carried out in conditions of poor hygiene and not always adequate temperature, often increased a lot the volatile acidity and many other defects. The subsequent improvement in winemaking techniques brought back the "governo", which spread in Chianti, but also in other Italian regions. Later, it disappeared in Tuscany (today, it is enough our sun, with good practices, to produce great wines). Similar practice has remained in cooler Italian regions (as the "ripasso" in Veneto).

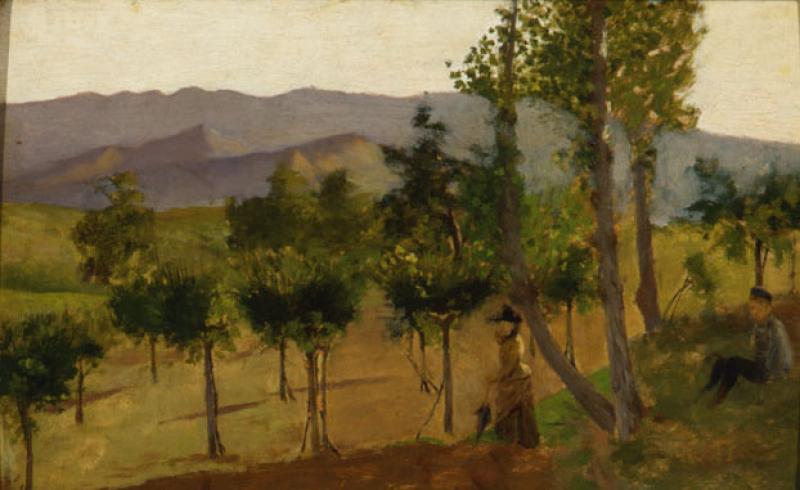

Now let's talk specifically about our territory. A suggestive description of the agricultural landscape of that time is found in the Tuscan Agricultural Journal of 1832. The article tells of the visit to the territory by three exponents of the Georgofili Academy of Florence: Cosimo Ridolfi, Lapo de' Ricci (agronomist, who signed the article) and Raffaello Lambruschini. The three guests visit Bolgheri, then they went to Castagneto, passing near the long Segalari Hill (see the map below).

Describing the vineyards of a noble family farm (Della Gherardesca) in the plain near Bolgheri, the piece tells that the vines are mainly supported by cane, broom or juniper poles, sometimes also by field maples ("loppi", in the Tuscan of the time). There is a criticism of the fact that the rows are too narrow and the vines too dense, as well as other pungent observations. The farm manager, Giuseppe Mazzanti replies to the criticisms with a proud letter, published on December 15th, 1832. According to Mazzanti, the rows are not too narrow, being 24 "braccia" wide (about 14 meters) and allow the intermediate cultivation of rotation of wheat, broad beans and lupins. This is clearly a mixed cultivation.

The visiting group then goes to Castagneto. Passing in front of the Segalari hill, they are struck by the care of the crops, dominated by vines sustained by field maples, alternating with fields of forage and cereals. They praise them, without lacking a certain condescension:

“… the Segalari hill draws the passenger's attention for its delightful cultivation. Small modernly built houses, fields planted with vines, and these leaned on field maples, flourishing vegetation of cereals and fodder, a certain care in the direction of the water and, we could say, a certain refinement that is not common in Maremma…”

The hill of Castagneto is described as steep, covered with vines and olive trees of remarkable vigor. After visiting the village and the castle, they descend towards the via Aurelia, crossing "arable land and vineyards".

From this and other testimonies, we can understand that, at the time, the mixed viticulture dominated here, as in all Tuscany and central Italy, that is, rows of vines were cultivated alternating them with strips of wheat or other. This not means that grapes were a secondary production. Let us remember that Chianti, in those periods, exported wine all over the world producing it from vines supported by trees (vine "married" to the tree, it is the traditional Italian name), in mixed cultivation with wheat.

As we have understand from this testimony, at the time (as today and even more) our territory was dominated by the great estates of noble families. Each farm was divided into severl "poderi". A "podere" is one little part of the estate, entrusted to a farmer family. On the other hand, around Castagneto and on the Segalari hill, due to the historical events that I mentioned here, there were numerous medium and small properties and there were much more buying and selling movements.

I tried to understand the dimension of local production at the time, but I found only very few data. They are also often affected by the modern prejudice of considering as vineyards only those with intensive cultivation (monoculture). Actually, the vast majority of the vineyards of that time was rapresented by the promiscuous viticulture, that was the local tradition since the Etruscan time. Excluding it means introducing a big error in the evaluations.

The University of Florence, under the guidance of Mauro Agnoletti, conducted studies starting from the analysis of data from the land registry of the time. Three historical moments have been examined: 1832, 1935 and 1954. I was amazed by the fact that they left a frightening hole in the middle (about 100 years), which includes precisely the period of maximum wine-growing expansion of the territory.

In 1832, which is still a moment of onset of agricultural development in the Maremma, the cultivated areas occupy 23.5% of our territory, with a prevalence of arable land. The study reports that the monoculture vineyard occupies about 35 ha (I remember that one hectare equals 10,000 square meters) and, curiously, it stops here, not considering that at the time intensive viticulture was the minority. So, I added up all the areas where the nineteenth-century cadastre explicitly reports the presence of vines with other crops, reaching over 360 ha, 1/4 of the cultivated areas. Of course it is not possible to compare the hectares of mixed viticulture with those of intensive, which we refer to with our modern models. However, we can understand that already in 1832 viticulture was very widespread in the area. I remember you that our territory is very small: the actual wine production is 1300 ha circa of vineyards.

The period of maximum growth of the farms took place in the following decades, with the birth of numerous vineyards, as evidenced in the books by Luciano Bezzini and Edoardo Scalzini, who examined the rich documentation left by the estates of that time. Unfortunately, there is a lack of overall data from this long and decisive period. Below, there is a sigle data, ase the below example.

In 1903, in the Farm Gherardesca of Castagneto, there were 750 ha of mixed viticulture and cereals, with the presence of 352,190 vines. There are also 22 ha of monoculture vines, of which 17.5 ha were dedicated to black varieties (with 144,514 vines) and 4.5 ha of white grapes (30,680 vines). Their density is comparable to the densest modern vineyards: over 8,000 vines per hectare in the first case and almost 7,000 in the second. If we divide the number of vines of promiscuous viticulture by this density, we can relate the mixed production to an intensive vineyard of about fifty hectares. In total, therefore, this single farm produced wine for an area comparable to about 72 hectares of dense vineyards.

The area planted with vines in 1935, according to the land registry study, is 301 ha, but again it only refers to intensive viticulture. This time there are no detailed data that allow me to calculate the mixed viticulture. There is only a generic "arable land with other trees" (which could include vines but not only) which occupies 1665.76 ha. However, we know that this is a period of decline in the area's viticulture. From the 1920s, the phylloxera (remember? It is the parasite that threatened to wipe out world viticulture) damaged locally as never before, after a first appearance in 1895.

Prof Agnoletti attributes to the phylloxera the main cause of the dramatic decline that local viticulture underwent around the middle of the twentieth century. The cadastral data tell us that in 1954 intensive viticulture had dropped to just over 7 hectares. Again, the study neglects the promiscuous one, it does not even tell us whether it was still present or not, except that the generic "arable land with other trees" has expanded to 2276.76 ha.

We know for sure that the viticulture crisis of the time gave way to other crops. The first half of the twentieth century saw the boom of olive trees in monoculture, which had an increase of + 300% throughout the province of Livorno. In 1925 Mussolini started the "battle of wheat", pushing towards the expansion of productivity and surfaces, which expanded as never before in Maremma. Fascism also stimulated the increase of houses scattered in the countryside, which had never been more numerous here. The fruit trees, such as the peach trees, and the horticultural crops also spread.

Stories of vineyards and farms

Let's now see in detail how the production was at that time, from the examination of the documents of the estates of the area made by Bezzini and Scalzini.

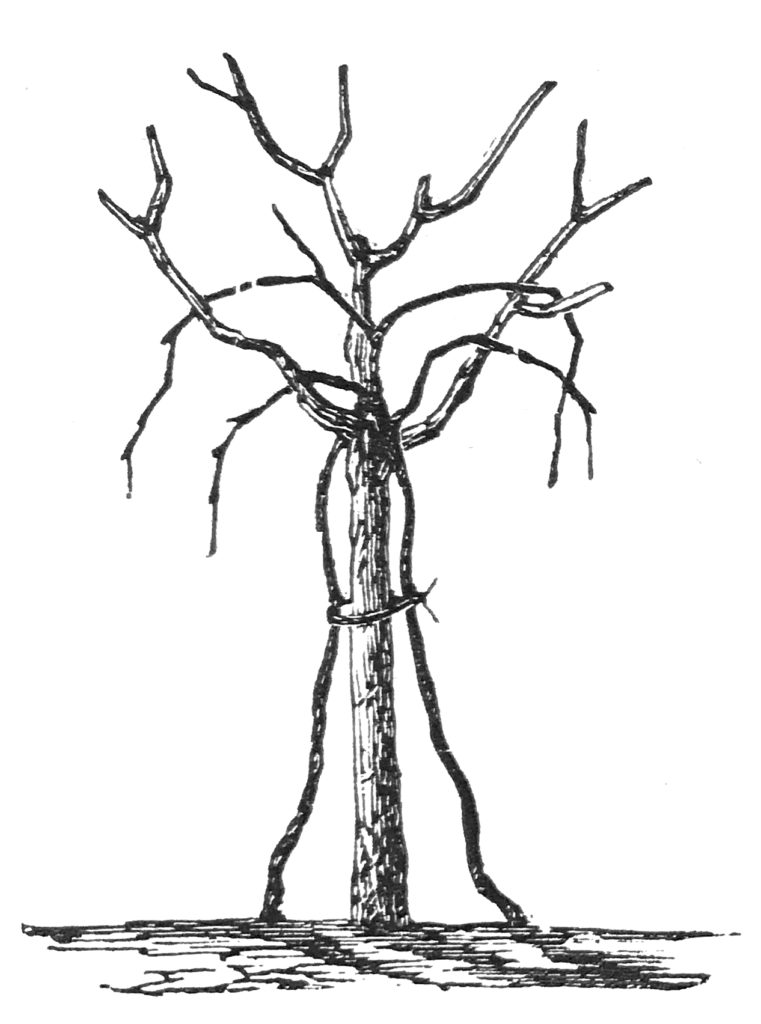

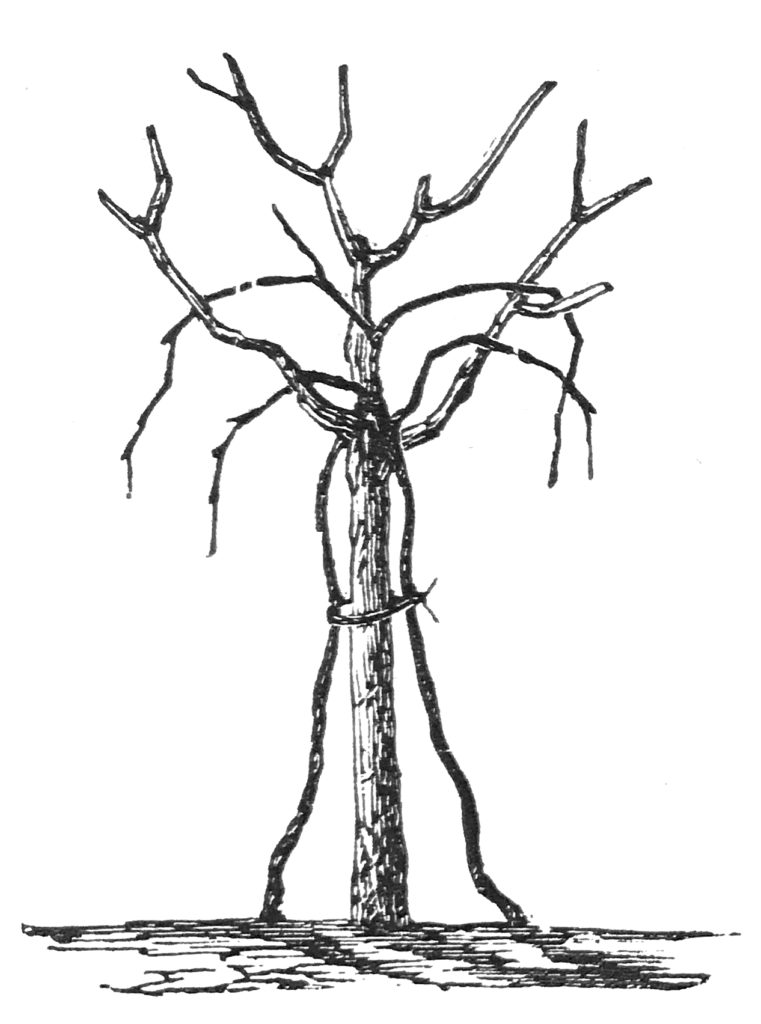

As we have seen, the vineyards were mostly made of vines "married" to trees, the ancient vine coltivation system of Etruscan-Roman origin that I have already talked about fro long. At the beginning of the nineteenth century, in Bolgheri, we often found the word "piantata", a term that has also remained in some toponyms. In the old agronomic language, "piantata" indicated married vines that pass the shoots from tree to tree, forming rows. However, it was often used improperly (and vice versa) to indicate the "alberata", i.e. the vines wrapped around a single tree. The local use of certain terms is not always easy to understand.

But we know with certainty that here, as in almost all of Tuscany and other central regions, the ancient Etruscan custom of field maples as supports remained. As wrote above, the tree was sometimes replaced by poles. I have personally seen still today in very rare old vineyards (see the photo below). Probably the version with poles was prevalent in the few monoculture vineyards at the time.

In the Tuscan agricultural texts of the time, the cultivation practices of the vine "married" to the tree are explained in detail. A reference text of the time is that of the botanist Saverio Manetti, entitled "Oenologia Toscana" (1773), published under the pseudonym of Giovanni Cosimo Villifranchi. He writes that the cultivation with the married vine allows to obtain excellent quality for the grapes and the wine, provided that this is set and managed in an optimal way, with the tree and the vine in an unexpanded form. Both of them were in fact kept low and adequately pruned. According to Manetti, but not only, the field maple is the best of many other trees, because it does not interfere with the optimal development of the vine: the roots take up little space and the crown can be easily contained with an appropriate pruning. This is the oldest form of agroecology.

The vineyards included, as was common at the time, several varieties. The wines were always born from a field blends. The main local varieties reported in the documents are Sangiovese, Vermentino, black Canaiolo, white Canaiolo, black Malvasia, white Malvasia, Tuscan Trebbiano, Aleatico, less common Mammolo and Pernicione (now disappeared). There are also French vines, often written with Italianized names, such as Gemè (Gamay), Carmené (Carmener or Cabernet franc), Caberné (Cabernet sauvignon), Scirà (Syrah). Mostly still wines were produced, especially reds (although sometimes white grapes were present in the blend), white ones in lesser quantities. There were basic and top wines. Sweet wines were also produced, especially made with Aleatico, and a slightly rosé vin santo, which is why it was called Occhio di Pernice (Partridge Eye). The production of white wines grew especially in the early decades of the twentieth century, due to the great market demand of the time. In this period, the arrival of Chardonnay, Clairette and Sémillon is also noted, as well as the first appearance of Merlot.

It was common at the time that the cellars were in the villages, especially as regards the small owners of Castagneto. You could smell the scent of wine during the fermentation in the streets of the villages, as told in the famous lyric of Carducci "San Martino" (Saint Martin's Day). For those like me who live in Castagneto Carducci (or even just know it), I imagine easily this windy day of early November (on the Saint Martin's day) while I'm looking from the top of the hilly village the stormy sea and the mist of the plain below.

The fog to the bare hills

soars in the thin rain,

and below the wind

howls and churns the sea;yet through the hamlet's alleys

from the fermenting casks

goes the pungent scent of wines

to touch a soul with glee.On the firewood, turns

the skewer crackling:

stands the hunter whistling,

on the threshold to seein the reddening clouds

flocks of black birds,

like exiled thoughts

as in the dusk they flee.

If fthe cellars were almost always inside the villages or the small owners, there were mixed situations for the large estates, with cellars in the village and even in the individual farmhouses. Usually, each farmer vinified his grapes separately and the wine was then taken by the estate owner for the part due to him. I found in only one case, at the time, the presence of a single centralized wine-cellar, in the Serristori estate (which was located in the southern part of the municipality).

Let's go back to the article of the three Florentines visiting the territory in 1832, as they describe the wines tasted in Castagneto:

“The common wine is not very intense but it does not have a brackish taste like many Maremma wines, and it is pleasant. The wines made with more accuracy, "for the bottle", are exquisite; the skill of the winemaker overcomes the quality of the grapes, or one conspires with the other. Aleatico and vin santo have a lot of grace and fragrance and are excellent; they are never too much sweet, nauseant, characteristics that displease all connoisseurs of local wines so much".

These praises stand out particularly in the newspaper which, on the other hand, is generally very hypercritical about the wines of the Maremma Pisana.

My interest was particularly focused on the history of the old Espinassi Moratti Farm, because it also included the vineyards that today are those of our winery, Guado al Melo. The Morattis, then Espinassi Moratti, created and expanded their properties starting from the end of the eighteenth century, until to create a very large estate. Giovanni Moratti bought the land, that today form the vineyards of Guado al Melo, in an area then called "Campo al Lucchese", on the first edges of the north side of the Segalari hill, in two times. In 1818, he bought a part from a small farmer, Giovacchino Balli, and in 1820 by the owner of the Segalari Farm, Giulio Bigazzi. In 1824 he also bought the neighboring "podere" Grattamacco from Bigazzi, where there was a farmhouse and formed a single large podere. The wine that was produced there managed to get high prices in the high society of Pisa, because it was “full-bodied and fragrant”. The success prompted the owner to take all the wine, including the part due to the farmer, giving him one of lesser value in exchange. The vines cultivated were the classic ones of the area already mentioned: Trebbiano, white and black Malvasia, Vermentino, white and black Canaiolo Bianco, Sangiovese, Cabernet sauvignon. In the twentieth century the prevalence of white varieties is reported, as well as the presence of Merlot. In the early years of the twentieth century, the farm experienced a period of crisis, but then flourished again in the 1930s. In 1925, the estate's wine also won the first prize of the Rome Wine Fair. In 1937, the Grattamacco farm, judged too large for a single family of farmers, was divided in two. The Santa Maria farm was born, with the construction of a new farmhouse, at whose service the vineyards of today's Guado al Melo remained. In the second post-war period, the estate began to be partially dismembered. In the 1960s, it yet included 22 hectares of specialized vineyards, among which the vineyard of Santa Maria is still mentioned, equal to 12 hectares, whose boundaries described are precisely those of Guado al Melo (between the Gelli's mill and the Grattamacco dyke). The vineyards of today's Guado al Melo were then sold, separated from the remaining Podere Santa Maria, to a local farmer who, as his sons told us, continued to produce wine.

“The wine is a lot and it is very good” and will have a great future

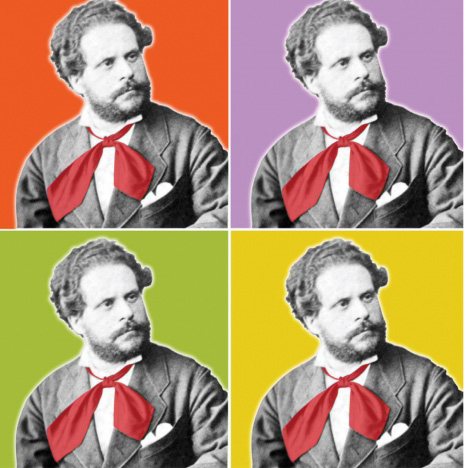

Finally, let's go back to Giosuè Carducci, Nobel Prize for literature, with whom we began this little journey and with which we conclude it.

The poet celebrated our land in his lyrics, even if he was not a native of the place (he was born in Valdicastello, in Versilia, norther in the Tuscan coast). He arrived here with his family at the age of three, following his father (a doctor). He spent the carefree years of childhood and early adolescence there, first in Bolgheri and then in Castagneto, and this land remained imprinted in his heart. He had the local wine sent to Bologna, where he taught, and he also consumes it abundantly during his visits to his friends, dedicated to banquets with a lot of wine, which he called “ribotte” (blowouts).

Carducci is the emblem of the great boom of wine in Bolgheri (and Castagneto area) during the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. As mentioned, the phylloxera destroyed the local production, giving space to other crops. However, as we all know, it will only be a pause: then, a new rebirth of wine will begin, which will be more extraordinary than ever (in the next post).

Bibliography:

Agnoletti M, "Il Paesaggio come risorsa, Castagneto negli ultimi due secoli", Ed. ETS, 2009

Agnoletti M., Paletti S., "Il ruolo del vigneto nel paesaggio di Castagneto Carducci fra l'Ottocento e l'attualità", Facoltà di Agraria, Università di Firenze, Overview allegato n.15 di Architettura e Paesaggio.

Bezzini L., Guagnini E., "Vini di Bolgheri e altri vini di Castagneto Carducci". ed. Le Lettere, 1996

De Ricci L. et al., "Corsa Agraria della Maremma", Giornale Agrario Toscano, 1832

Garoglio G., "La nuova Enologia", eds. Istituto di Industrie Agrari Firenze, 1963

Scalzini E., "Inventario dell'archivio della fattoria Espinassi Moratti di Castagneto Carducci (1781-1981), ed. Comune di Castagneto Carducci

Villifranchi G.C. (alias Saverio Manetti), "Oenologia Toscana", rivista il Magazzino Toscano, 1773

Webinar domani con Michele Scienza

Questo periodo di pandemia ci ha resi famigliari con nuovi termini e modalità di incontro. Così eccoci ad un nuovo webinar, un seminario a distanza che ci permette di incontrarci nonostante tutto.

Si terrà lunedì, domani, alle ore 19.00, organizzato da Alberto Levi, per parlare di Bolgheri, vigne ed artigianalità.

Per informazioni www.albertolevi.it

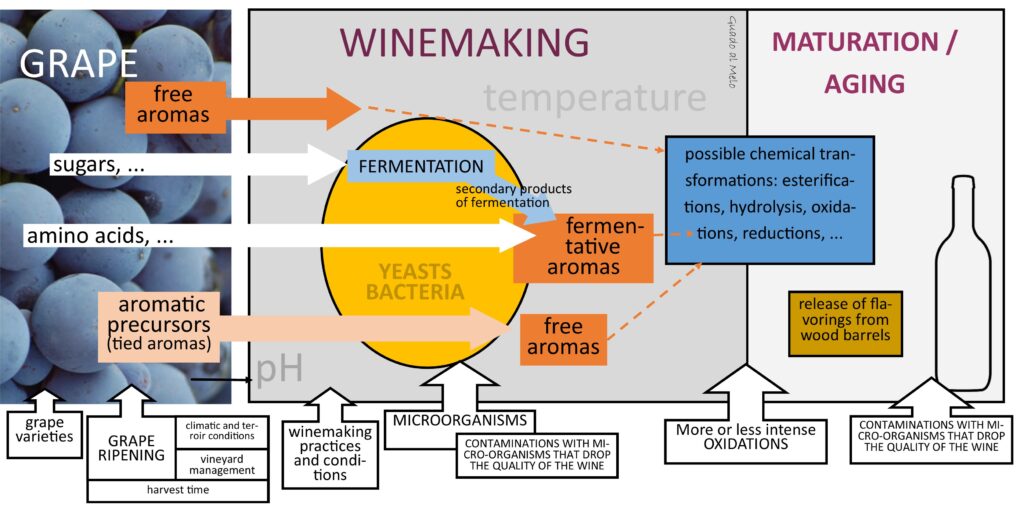

From the vineyard to the bottle: the magic of the scent of wine.

The main part of the wine charm is represented by its aromas. I'll tell you how they are born and how it is possible a so high diversification of them.

(cover picture from Isak S. Pretorius, 2017 Critical Reviews in Biotechnology, 37:1, 112-136)

How many are the wine aromas? It has an incredible aromatic richness and diversification. Some wines are more simple, with few perfumes. Some others have an amazing complexity. Each wine is not identical to another. You can also find difference between wines from the same area or produced with the same grape varieties.

How is such a great complexity and diversification possible?

"Strawberries, cherries and an angel's kiss in spring

My wine is really made from all these things"

(Summer Wine, by Nancy Sinatra)

Oh, oh summer wine / Strawberries, cherries and an angel's kiss in spring / My summer wine is really made from all these things / Take off your silver spurs and help me pass the time / And I will give to you summer wine / Oh, oh summer winee"

I will now try to explain how the aromas of wine come from the vineyard and reach the bottle. Above all, I will try to make you understand where all the aromatic diversity that wine can express comes from, how it is possible to enhance it in production or, vice versa, lose it.

In the following boxes there are some simple basic information on aromatic molecules and the smell, also useful for understanding some specific terms that are very often used in the world of wine. Immediately after, we will enter the heart of the scent of wine.

Today, thanks to increasingly sophisticated analysis techniques, we have come to define hundreds of aromatic components in wines from a chemical point of view. The aromatic molecules, that is the substances responsible for perfumes, are of many different types. However, they have in common the ability to interact with our olfactory receptors, located in the nasal cavity. Their aromaticity depends on the fact that they are volatile, that is, they have a marked tendency to pass from the liquid to the gaseous state. They are able to reach our olfactory receptors, using two ways. They can pass through the nose when we smell. They can also reach them from the mouth, when we have wine in the oral cavity, through the retro-nasal passages. About wine, we call aromatic profile the entire range of aromas that it expresses.

Why is the nose (of expert people) still the privileged tool for making certain decisions in wine production? It is not easy to trace to the aromatic profile of a wine starting from the chemical analysis, because the aromatic expression of these molecules is not always easily predictable. Some of them are perceptible only above certain concentrations, others are dominant in the profile even if present in little more than traces. Some change the type of aroma depending on their concentration or can even become unpleasant. Certain aromatic compounds have a synergistic action: if they are present together, they give a different smell. Not only that: the studies done so far have shown that it is very difficult to predict the volatility of an aromatic molecule in a complex mixture (such as wine). The volatility of a molecule is influenced by the others. Even the non-volatile part of the wine (made up of polyphenols, polysaccharides, glucose and other substances) has an influence on the volatility of the aromatic component, in a way not yet fully understood.

Smell is an incredibly complex and very powerful sense. We have about a thousand different types of olfactory receptors. Each aromatic molecule activates a different combination of these receptors. Therefore, considering a potentially infinite combinatorial possibility, our nose can recognize a very high number of odorous substances. But it also has a very individual component. First of all, our individual olfactory capacity is influenced by genetics. This not only means that someone is more gifted than others, but also that different people can perceive sensations differently. Furthermore, important psychological factors also are present. Linking an aromatic sensation to a name (rose, strowberry or other) gets involved our olfactory memory, that is the memory of having already smelled a similar sensation and having classified it with that name. In a complex blend like wine, the aromas are not always clear and defined. The associations we can make are therefore not unique: we connect a certain odor sensation to the one that is most similar in our memory. Hence, this connection can vary depending on our experiences. Surely, people who are more used to smelling perfumes have an olfactory memory that is more trained to recognize and denominate certain sensations. Furthermore, the numerous studies carried out so far have also shown that our olfactory capacity is influenced by the situations: by the mood of the moment, by our (unconscious or not) prejudices and expectations, by the suggestion created by other people, … For all these reasons, in sensory analysis researches (where the tasting is not for pleasure but to try to describe a wine in the most objective way possible), the tests are made by groups of people, organizing them and examining the results according to statistical evaluations.

Given that there is an rilevant individual component, people that drinks wine for pleasure should not feel in awe of freely expressing his sensations. If you want to improve your smell capacity, it's not that difficult. It is enough to train yourself often, smelling single aromas (fruits, aromatic herbs, spices, etc.), so that they are marked in your olfactory memory.

How the wine aromas are born

Hearing about peach or rose or berry scents in wine, inexpert people often ask if these aromas are added during wine production. The answer is that there is no need: all the aromas of wine originate from grapes and winemaking process. Adding flavorings could be a shortcut. In Italy, this practice is prohibited by law.

How then is it possible that wine can smell of peach or rose (or many other things)? It is possible because the molecules that give these aromatic sensations are common among the different species of the plant kingdom. In this context, the grapevine (Vitis vinifera L.) is decidedly particular: it has a very large potential aromatic richness. Throughout history, this characteristic has made grapes the queen of raw materials with which to produce a fermented drink.

However, the grape itself does not have many smells. There are some grape varieties more fragrant than the others, which are defined as “aromatic”, such as different Moscato. Most of the aromas we can find in the wine derive from grape but they are molecules that are in a non-odorous form in the fruit. They are called aromatic precursors. They are not perceptible to the smell because the aromatic molecules are linked with others that prevent their volatility. They can become volatile only if this bond is broken. That can occur during winemaking, as we will see.

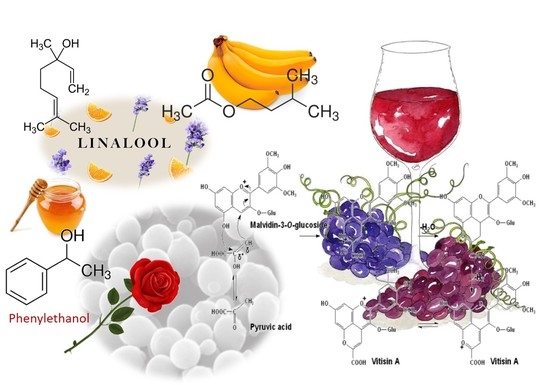

The varietal aromas are numerous. We can group them into 4 families which, as mentioned, are widespread in the plant kingdom, so they give aromas that recall other plants, fruits and flowers:

- a very extensive family is that of terpene compounds, which give aromas of rose, linden, lily of the valley, lemongrass, … but also that composite sensation of "muscat";

- carotenoids derivatives, which give complex aromas of flowers, exotic fruits, apples, violets, tobacco, tea, berries, …;

- metoxypyrazines, which give notes of green pepper, asparagus, earthy hints;

- thiol compounds, they can contribute in several cases to the notes of cassis, passion fruit, broom, tomato leaf, peach, eucalyptus, … They also develop in fermentation, where they are often responsible for bad odors.

Some aromatic molecules can develop when the grapes are pressed: they are called prefermentative aromas. The most typical example are aldehydes, which give hints of cut grass (not very pleasant). When the grape is mashed, some enzymes come into contact with the bloom, the waxy material that covers the berry peel, and transform it. The stronger the mechanical stress to which the grape is subjected, the more these substances originate. In reality, today they are much less important than in the past: it is now common to use crushing or pressing machines that act very softly.

Mainly, other aromatic molecules are formed by the action of yeasts and bacteria during fermentation reactions, as secondary products of the process. Other aromas are produced by the microorganisms by other metabolic pathway, starting from substances that are present in the must / wine (especially amino acids). All these aromas are called fermentative. All together, they represent the specific aromatic base of the wine, that “vinous” sensation that makes us understand that we are smelling wine even with closed eyes. This aromatic core, which prof. Ferreira of the University of Zaragoza defines a "vinous matrix", it is a set of heterogeneous compounds. It includes higher alcohols ("vinous" notes), ethyl esters of fatty acids (honey, wax, different floral aromas, …), acetic esters of higher alcohols (banana, apple, candy, rose), volatile fatty acids (acetic acid, …). So far, 27 have been identified. In each wine they can be different in presence and quantity. Ethyl acetate, the most important ester in wine (but also the least positive) is responsible for the notes of acescence (not acetic acid, as is often believed). It is produced by yeasts in fermentation in small part. At low doses, it seems to contribute positively to the aromatic profile. When it is more, it almost always derives from contamination of acetic bacteria.

I have described to you what is the basic core of wine aromas. Then, other modification can occure that can enrich or alter the wine profile. Malo-lactic fermentation, mainly carried out by the bacterium Oenococcus oeni, leads to the formation of other fatty acids and esters, which can give a buttery smell. During winemaking and aging, other chemical reactions can occur which act on aromas and modify them: esterifications, oxidations, reductions, hydrolysis, etc. Some wine containers may release aromas (expecially new oak barrels or if you add wood chippings) or can create conditions that favor oxidation (concrete, amphora). If the aging is done on the lees, there are typical aromas of bread crust or yeast. I will not enter now in the very complex part of what are defined "olfactory wine defects", which we will talk about another time.

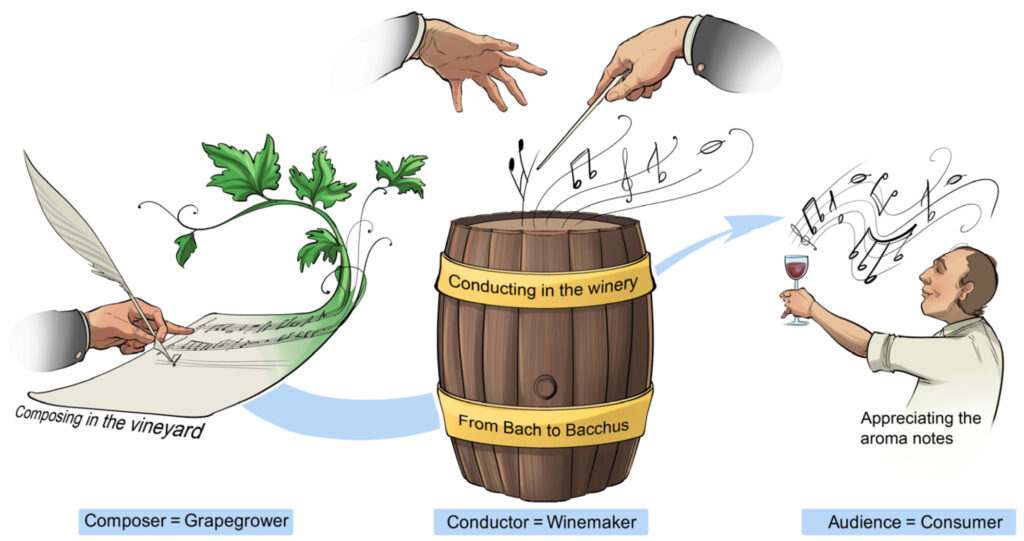

In general, the aromatic profile of wine is based on the vinous matrix on which the aforementioned varietal aromas are grafted. All these aromas integrate with each other like the instruments of an orchestra, in a complex relationship between them and with the non-volatile component of the wine, which modulates the olfactory expression.

Why is there such a large differentiation between wines?

Most of the varietal aromas accumulate more or less progressively during the ripening of the grapes. The metoxypyrazines, on the other hand, follow the opposite path: they are highest in the small green berry and are demolished during the ripening. We can therefore understand that the conditions in which ripening takes place (the terroir, the climate, the vintage, the choices and cultivation practices) can change the internal balance of the fruit, influencing the aromatic components. It is therefore confirmed that the quality of the grapes is truly fundamental for a great wine. Poor, poorly grown, unhealthy grapes, etc. they will never give great products. Likewise, the decision of when to harvest is important. If the harvest is done before or after, different aromas are obtained. For example, the hint of green pepper is often described as typical of Cabernet sauvignon, but is only partially true. The content of methoxypyrazines, responsible for this aroma, becomes important in wine if grape is harvested too early. The methoxypyrazines are also influenced by environmental conditions: it is easier to find them in wines of cooler climates than in warmer ones with high solar irradiation (where they are degraded much faster).

The aromatic precursors, as mentioned above, are released during the winemaking. Therefore, there is a reserve of potential aromas in the must that is derived from grapes, but it is not automatic that they'll be expressed in the wine. They can be expressed or not, in whole or in part, depending on the winemaking (and the subsequent phases) conditions and practices. These conditions also influence the fermentative aromas, the vinous matrix I mentioned above.

There are many studies on these aspects. It has been showed that various elements influencing yeast activity can modify the aromatic component of wine. Among them, I remember the presence and composition of some important nutritional factors, essential to yeasts as sources of nitrogen and vitamins. An influence is also due to the pH and to the temperature. Nutrients and pH depend on the qualitiy of grape: if it ripened with optimal conditions, the managment of the vineyard, the moment of harvesting … It is possible to add additives to adjust these elements, but it is an industrial approach, that does not enhance the identity of the grape varieties and territory. The pH can vary in other ways, for example by the presence of some microrganisms. In the past, it was frequently modified by the release of substances from concrete containers.

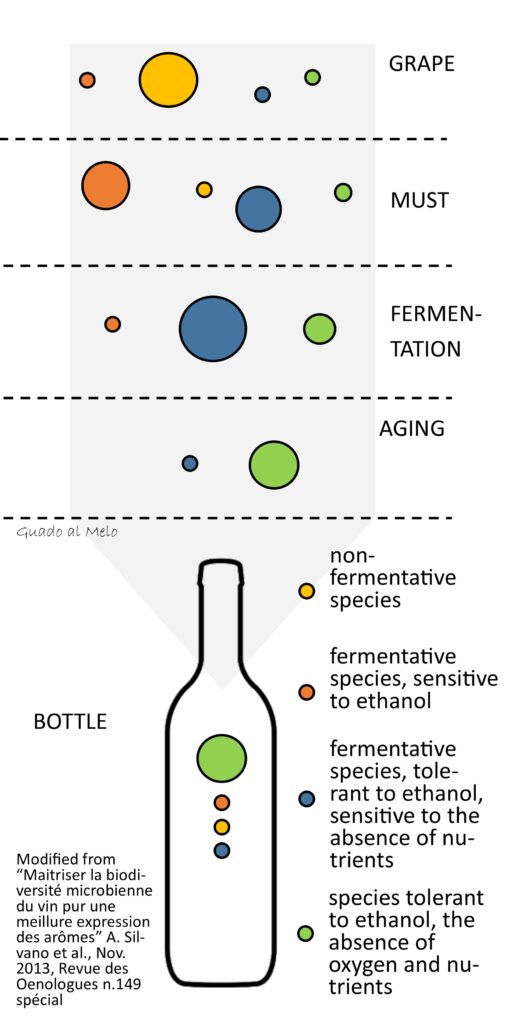

Another important element in modifying the aromatic composition of a wine is represented by the type of microorganisms (yeasts and bacteria) that are present. Each type (species and strain) produces different quantities and proportions of the fermentative aromas. Therefore, the higher the biodiversity of yeasts, the more complex wine is. However, let us remember that all these elements are connected: for example, if we have a high biodiversity of yeasts but poor quality grapes, there will still be no aromatic complexity. However, the microorganism pool need to be managed carefully, to avoid the presence of those that have a negative action for the wine. I would like to underline that in any case no pathogenic microorganisms for humans survive in wine, due to its acidity.

As I have already told in a previous article (here), a heterogeneous group of microorganisms goes into the must: they derive from grapes, harvesting tools and the cellar. The group changes with the territory, the climatic conditions, the insolation, the different variety of vines, the management of the vineyard and the cellar, … Actually, most of these microorganisms die in the passage from grape to must. There are very different conditions with respect to the surface of grapes or objects: there is no oxygen, there is a very high sugar concentration, the temperature changes, etc. During fermentation, the conditions change again and the populations of the microorganisms yet change. Above all, those who suffer from the progressive increase in alcohol succumb. Some strains also have the ability to produce substances capable of eliminating competition. We know that Saccharomyces will become prevalent in conducting fermentation. However, non-Saccharomyces, both in the initial stages and when they become secondary, can enrich the must with metabolites that contribute positively to the wine's aromatic profile, expanding its complexity. In the figure below, the microorganisms indicated with the green dot are negative, which you would never want to have in your cellar, much less in the final bottle.

It is possible to schematize the different groups of microorganisms in 4 families, according to their behavior:

- Non-fermentative microorganisms: these are those prevalent on the grape skins but which decrease significantly with mashing (e.g. species of Cryptococcus, Rhodotorula, A. pullulans, various species of Serratia, etc.)

- Fermentation species but with low tolerance to ethanol (alcohol): they increase in the must and participate in the initial stages of fermentation but then, they decrease with the progressive accumulation of alcohol and for other reasons (different species of Candida, Pichia, Lactobacillus, G. oxydans, etc.)

- Fermentative species, which tolerate the accumulation of ethanol. At the end of the processes, however, they decrease because they suffer from a lack of nutrients (Saccharomyces cerevisiae, Oenococcus oeni, …).

- Species resistant to the absence of nutrients and to sulphites: some microorganisms can remain in high numbers even after the end of fermentation because they can feed on other compounds and can also resist the addition of sulphites in bottling. Among these, there are some very dangerous ones, such as Brettanomyces bruxellensis, which causes really unpleasant smells (smell of stable, horse, etc.).

The understanding of these mechanisms has also led to the selection of yeasts that allow to change the aromatic profile of the wine, both for commercial choices and to make up for production / technical deficiencies (poor quality grapes, mistakes, etc.). In this way, however, wines that do not express the particularity of their genius loci (the spirit of the place, or terroir) are produced. They can be quite good, but similar to many others that have been produced with the same practices. They are generally simple wines, with very few aromas, according to a serial production that is the same every year.

If you have followed me this far, you will have understood how nature gives us a complexity that we humans can hardly equal. With interventions that we believe are improving, we actually reduce this wealth to the few elements that we can control. When you hear about artisanal wines, natural wines or other similar definitions, we are talking about that: winemakers who try to preserve all the peculiarities of their vineyard to the maximum and enhance it in their wines.

However, it is not easy to make a wine by managing all this complexity and being able to obtain good / great results. Mistakes or wrong management from the vineyard to the cellar can give rise to simple, mediocre or even unpleasant wines. Here lies the artisan value of the wine. Managing a vineyard and making wine are jobs that require a lot of knowledge, as well as a great deal of experience and a certain degree of talent. In other words, a great deal of professionalism is needed. Unfortunately, today this last word is definitely underestimated: sometimes, improvisation arouses more sympathy or is (erroneously) associated with something more "genuine". Knowledge does not necessarily imply more disruptive interventions on wine: it is often the opposite. The expert winemaker understands how to work well in subtraction, not in addition.

A common metaphor (but that gives a good idea) is the one that associates the birth of wine with music. The grape is the composer, even if I would also add the territory, the vintage, the microorganisms, etc. All these elements are directed by the winemaker, like an orchestra conductor, who knows how to get the most out of each one but, above all, manages to make them work well together. (picture from Isak S. Pretorius (2017) Synthetic genome engineering forging new frontiers for wine yeast, Critical Reviews in Biotechnology, 37:1, 112-136, DOI: 10.1080/07388551.2016.1214945)

In conclusion, the birth of the wine aromas is a kind of magic, which depends on an inseparable union: nature (the grape, with all its differences linked to the territory and vintage) and man (with his work, culture, traditions and choices, as well as his ability), as the poet wrote:

"Drink it, and remember in every drop of gold, in every glass of topaz, in every spoon of purple, that autumn worked for to fill the vessels with wine; and, in the ritual of his work, the simple man has learned to remember the land and his duties, to diffuse the canticle of the grape.

(Pablo Neruda, Ode to Wine)

Bibliography:

Trattato di enologia, P. Ribéreau-Gayon et al., 2013, Edagricole

Aromes des vins, Dossier spécial de la Revue des Oenologues, n.149 Nov. 2013

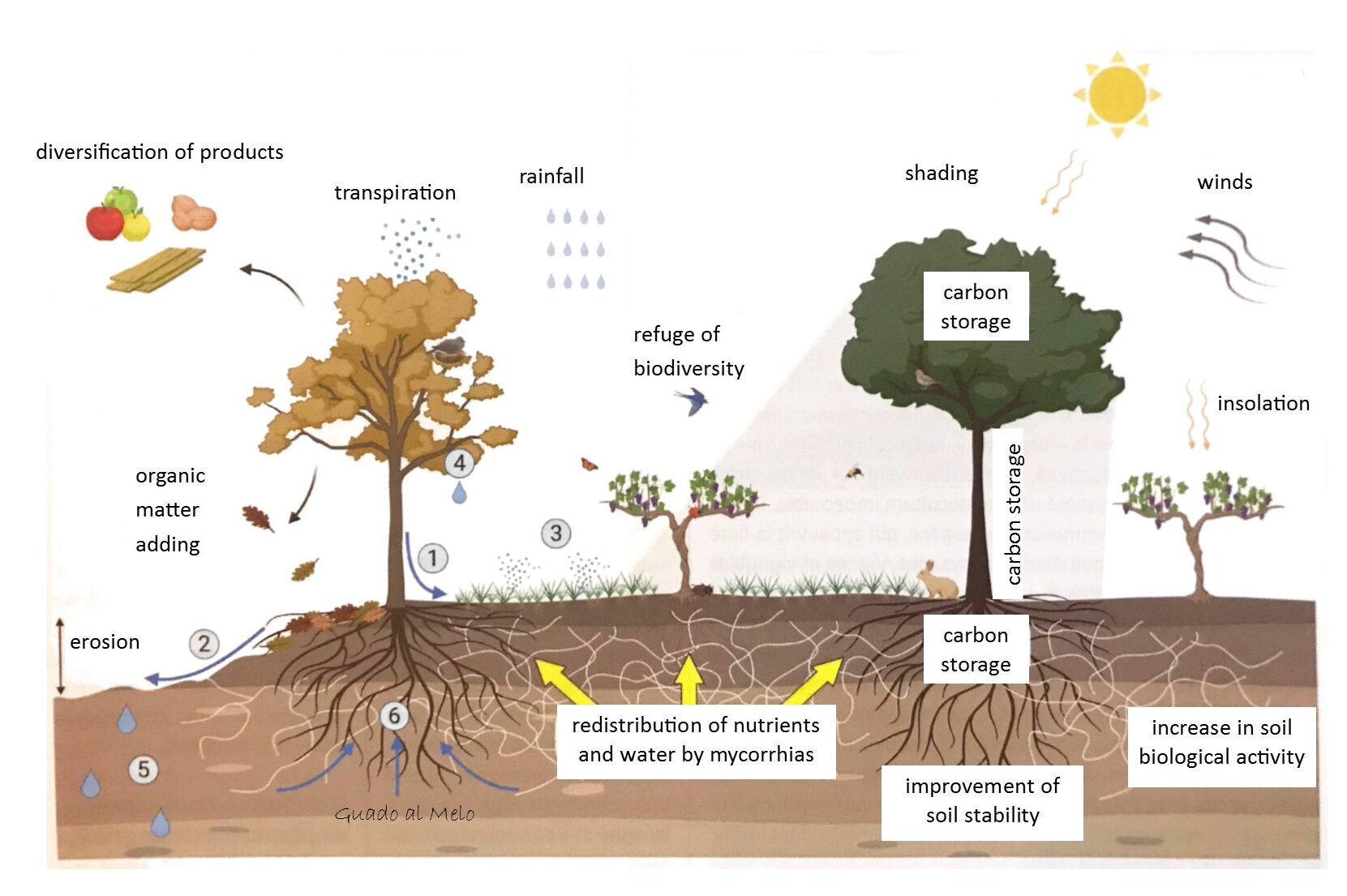

Agroecology in the vineyard, our present and future

The visitors to our vineyards and territory are particularly struck of finding an uncontaminated environment. They are impressed by our grassy vineyards, made by little particles bordering the wood, alternating with rows of olive trees, fruit trees and hedges. This vineyard managing (perfectly integrated into the environment and in association with other plant species) is the result of an ancient tradition and precise agronomic and environmental choices, which arise from agroecological studies.

[one_second][info_box title="What agroecology is?" image="" animate=""]

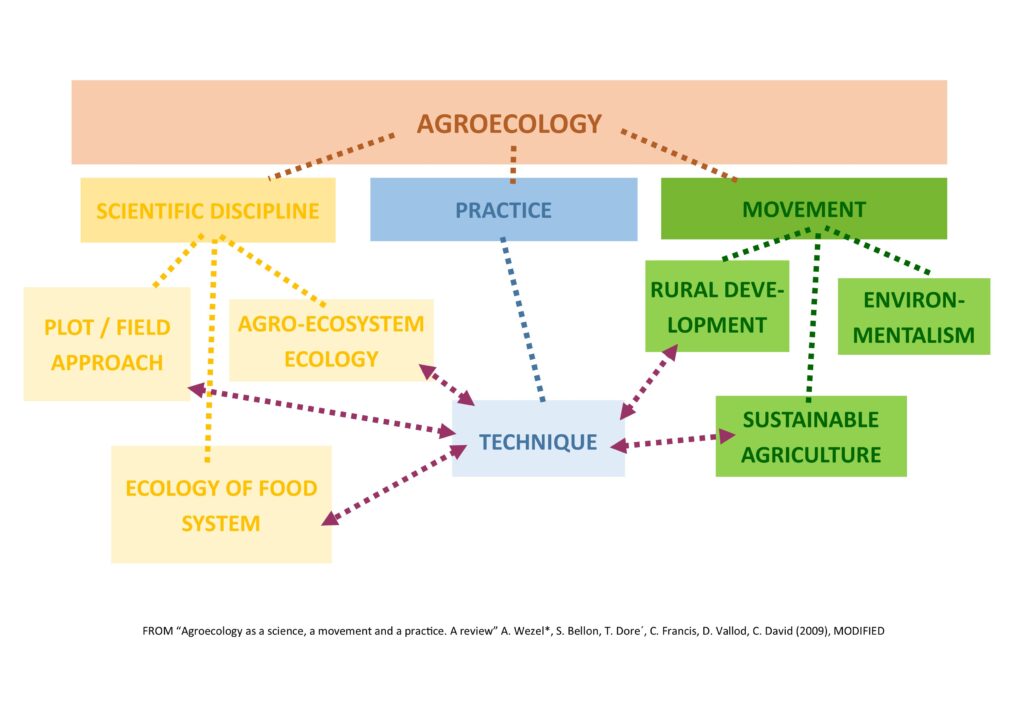

Agroecology arises from the fusion of two areas that may seem, at first, very distant: agriculture and ecology. Ecology deals with studying the relationships of a living being with its environment and with the other living beings that populate it. Agroecology applies this approach to a very particular ecosystem, the agroecosystem, the one domesticated and managed by man.

Agroecology was born around the 1960s as a science that studies these aspects in an interdisciplinary way. It has also taken on the characteristics of a political movement in Latin America, integrating within it all the management of the human food system.

Agroecology is one of the key concepts in sustainable management of viticulture. In particular, it concerns the integration of the vineyard in the environment and the preservation of its biodiversity. In other words, on agroecological vision, the vineyard is considered as an integrated ecosystem, where various subjects interacting with each other (vines, surrounding flora and fauna). If appropriately managed, this ecosystem can find an optimal balance, both for better cultivation and for preserving the environment and the landscape.

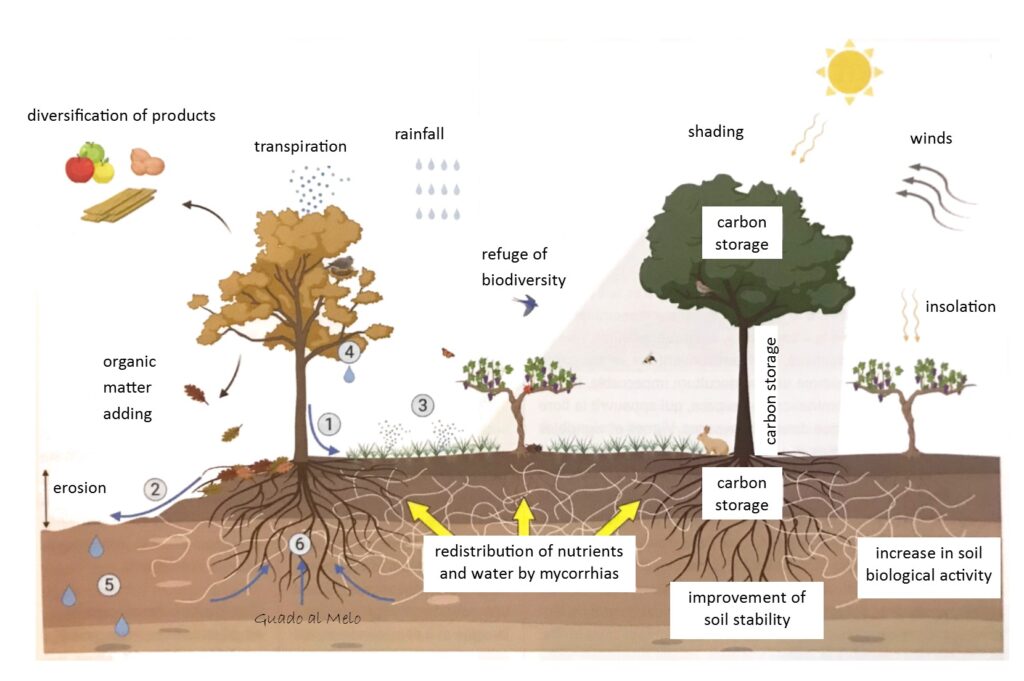

I focus this article on the association of the vine with other plant species, but the same happens with the animal world. A classical example is the application of biological control, based on some insects or mites which carry out their life cycle at the expense of species harmful to the vine. In the recent decades, interactions with even smaller organisms, such as bacteria and fungi, are increasingly being understood. Some of them are harmful, but some instead have interchange functions with the plant, which lead to precious symbionic associations (where both partners get something useful). The best known example is that of mycorrhias, fungi that colonize outside and inside the roots of the vine. This association significantly improves the supply of water and mineral nutrients, as well as the photosynthetic capacity in general. The most recent studies are also increasingly focusing on the microbiota that populates the vine leaves (the set of populations of microorganisms that live in these spaces). Several of them seem to play an important role in maintaining the health of the plant. Some bacteria have been shown to inhibit or delay the growth of harmful fungi for the vine. Some practical applications are also being developed. [/info_box][/one_second]

The amazement of these people is due to the fact that the viticultural landscape of many wine world areas is often very different. It derives from a different management, born with the modern era of winegrowing, which isolates the vine as much as possible from all living forms: bare soil, large areas of vineyards, excessive use of pesticides that (almost) "sterilize" the vines. This model, which has dominated for decades, has now shown all its limits.

The agroecological management of the vineyard was often considered a niche choice, a wrong legacy of the past or a bucolic vision by radical winegrowers (as someone told us!). Today, however, it is increasingly affecting the wine world. More and more scientific publications recognize this system as a valid agronomic model, which represents the best prospect for an increasingly sustainable future of viticulture.

The plant intercropping in the vineyard is part of Italian tradition from thousands of years, even if this approach has been lost in many territories. The most common viticulture in the history has been heterogeneous, with vine rows of vines alternating with other crops. Moreover, the trees often were the support of the vines. Do you remember the "married" vine to a tree, originated in the Etruscan-Roman epoc? It remained the main winegrowing form in the countryside of central-northern Italy until the mid-twentieth century. (I've talked about it several times, mostly here and here).

My talk is not about a naïve or old-fashioned winegrowing. Certainly, the modern era of viticulture has made us learn a lot, but it has also had indisputable excesses. By now, we have understood that viticulture must be sustainable from all points of view: not only for an optimal production but also for the protection of the environment and our health. To achieve this, we have to do the best synthesis between the different paths, taking the best of each.

Research is increasingly demonstrating that the association of vines with other plant species contributes to improving various aspects of viticulture, as part of a whole sustainable management. Let's see, in brief, the main advantages.

The most immediate positive aspect is on the landscape. The geometric lines of huge extensions of monocultures can have some charm. But a landscape where different elements alternate is certainly more beautiful and satisfying. Beauty is not a negligible factor, it fills our eyes and heart. However, the agroecological management does not stop at a beautiful postcard. It gives even more important advantages, both of natural environmental and agronomic, as we shall see below.

An environment rich in different plant species allows greater preservation of biodiversity and the environment. Today, there is a lot of talk about biodiversity in the vineyard and its usefulness on biological control. It is easy to realize that insects or other useful organisms can't try their best life condition in a monoculture environment, where also there are a large use of pesticides often. An environment with numerous plant species is much more attractive. It has many blooms for many months, as well as offering different habitats. Moreover, the vineyard also becomes a sort of "green passageway", which can be crossed by small animals, in their movements among woods and scrubes.water cycle

Research has shown how the presence of trees, shrubs and grass affects the micro-climate of the vineyard. Climate changes are leading to increases in average temperatures, which are causing more and more phenomena of acceleration of grape ripening. Extreme meteorological events are also becoming increasingly frequent, such as torrential rainfall, accentuated drought, etc. The presence of vegetation may be not decisive, but it improves the situation. For example, hedges and trees can be an obstacle to strong winds. The presence of rich vegetation improves local hydrometry, thanks to the transpiration-evaporation of the leaves. The effects of frosts also decrease. On the other hand, in warmer environments, partial shading contrasts the stresses due to thermal excesses and a too intense solar radiation, ...

Trees, shrubs and grass cover have an important influence on improving the quality of the soil. They cause an increase in organic matter and the biological activity of the rhizosphere. One of the most important problems of our Mediterranean climate is the low average presence of organic matter in the soils, due to mineralization cycles that are too accelerated by high temperatures. The numerous roots that explore the soil at different depths facilitate the exchange of matter, as well as helping to maintain a certain porosity that buffers excess water and, on the other hand, reduces drying and erosion.

In general, all the energy flows change: light irradiation, wind turbulence, water and nutrient cycle. For example, studies have highlighted the differences of the carbon fixation cycle in situations of "bare" vineyards compared to intercropping ones, to clear advantage of the latter

In particular, the presence of a rich vegetation determines a positive effect on the rhizosphere microbiota. So, the soil is more rich in fungi, bacteria, earthworms, etc. The presence of mycorrhias increases, because these not only colonize the vines but also other tree species. These fungi, as demonstrated, have positive effects on the photosynthetic capacity of plants but also on their ability to explore the soil for the supply of mineral salts and water. The extra-radical mycelium of the mycorrhias can colonize several plants at the same time, both vines and others, creating a sort of inter-specific cenosis. The presence of more plant species can lead to a greater differentiation of the mycorrhizae present, compared to monoculture, increasing the probability of their spread and survival. The presence of diversified communities of mycorrhias has also been shown to speed up the colonization time of the roots of young vines.

The traditional heterogeneous winegrowing derives from ancient practices, sometimes done with wisdom, sometimes casual. Today, the vineyard agroecology born from studies on the parcel to understand the best arrangement of trees and bushes, the choice of the best species both as essences and as size, etc.

However, I believe that the presence of local species, even spontaneous ones, creates a specific association that is much more interesting than too-constructed projects, also falling within the general concept of genius loci (or viticultural terroir) of that vineyard. We must not forget that one of the main goals of sustainable viticulture should be to minimize human inputs. I think that a too artificial construction of a "false" naturalness is a contradiction, overall if it needs continuous human interventions to be maintained. Optimal management should lead to an agro-ecosystem that balances itself without external interventations as much as possible.

For example, the spontaneous meadow has undoubted advantages over the sown one. Numerous studies have shown that the accumulation of nitrogen available in the soil thanks to the green manuring of some legumes is not significantly different from what can be obtained with spontaneous meadow. If there are no other obstacles, why not leave it to nature, avoiding continuous sowing? The ecological and management advantages are evident: the uses of the tractor are limited (fuel consumption is reduced and too many inputs that compact the soil are avoided), expenses are reduced (it is useless to buy seed when the lawn regenerates from itself), etc. I think it is a contradiction to talk about biodiversity in the vineyard and then set up monoculture also in the soil covering. The spontaneous meadow develops different species, that bloom in different times, in order to create an environment more in tune with the seasons, much more attractive for the local micro-fauna.

I conclude by returning to what is the highest form of association of the vine with other plant species: the vine "married" to the tree, that we have been studying in the field at Guado al Melo for several years. This traditional ancient form is snubbed by the Italian wine world. There is a closure: this vine-training system is seen as old and useless.

Curiously, I am finding instead more and more interest on "married vines" in the worldwide professional literature. More and more, I find articles and books on the subject, as in the special of the Revue des Oenologues that I quote at the bottom.

As I have already told in the final part of this article, the Romans brought this vine-training system from Italy to the rest of Europe. The French historically abandoned the "married" vine long before us, but they are returning to rediscover it as a interesting path for a more sustainable future of viticulture. For example, the OIV has awarded as best book of 2020 for sustainable viticulture ("durable", in French), a text that talks about intercropping between vine rows, including the "married vine" training system. I'm talking about "La vigne et ses plantes compagnes" by Léa Darricau and Yves Darricau, ed. La Rouergue (2019).

I want to invite the world of Italian wine to wake up. As has already happened too many times for many wine issues, will we wait to understand the importance of our tradition when the French will have taken it in the world as their? Will it seem interesting to us then? Let's meditate!

"Pratique viticoles inspirantes - Agroécologie en action au service du vivant", Revue des Oenologues.., Dossier Spécial, Nov. 2020, n.177

“Agroecology as a science, a movement and a practice. A review” A. Wezel*, S. Bellon, T. Dore´, C. Francis, D. Vallod, C. David (2009), Agronomy for Sustainable Development29(4):503-515

"Vine Roots", by E. Archer and D. Saayman, 2018 The Institute for Grape and Wine Sciences, Stellenbosch University

"La nuova viticultura", a cura di A. Palliotti et al., 2015, Edagricole.

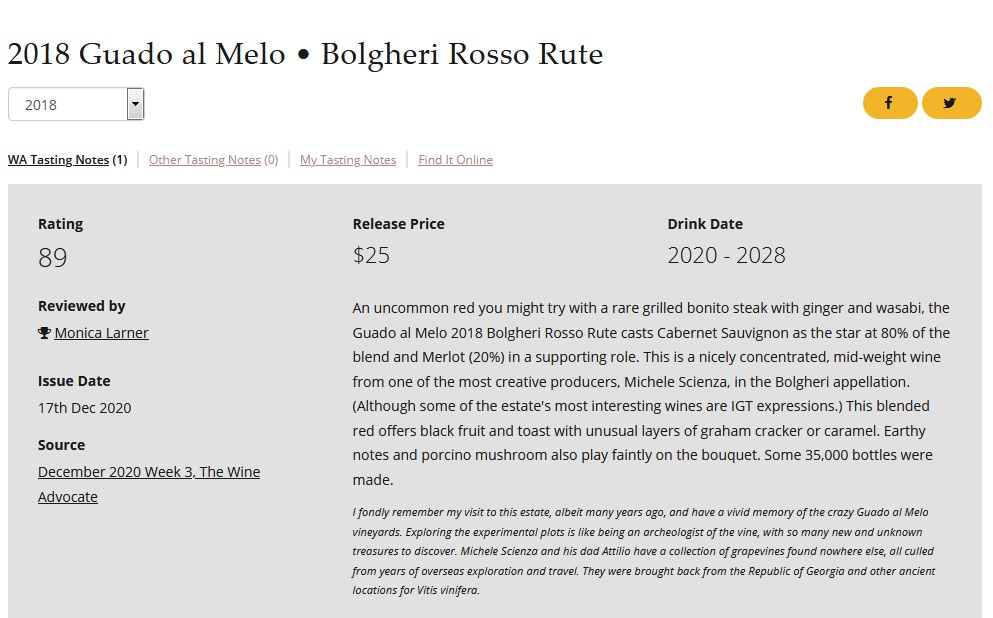

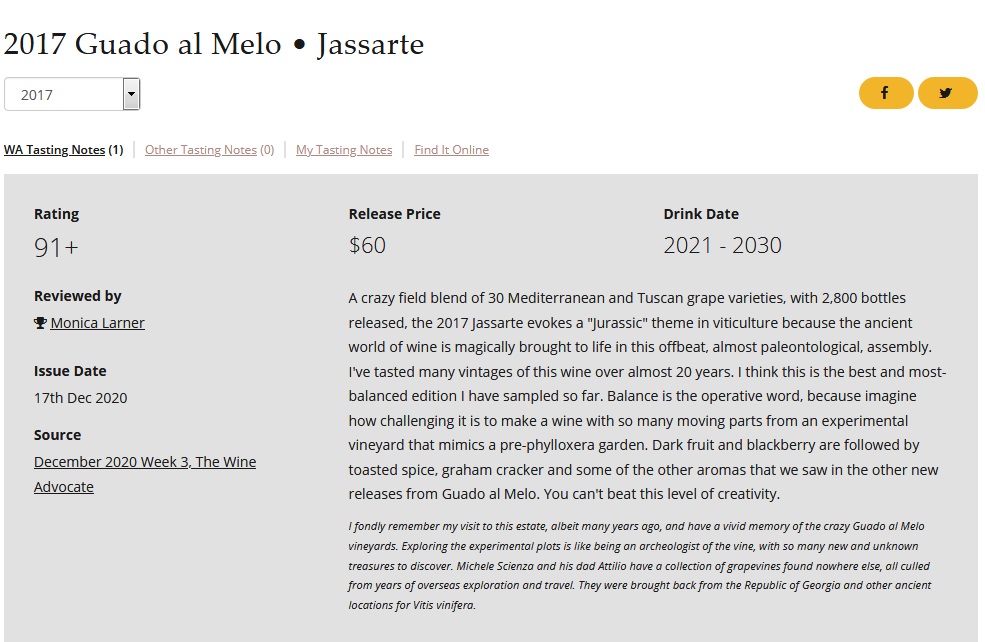

Michele Scienza, according to Wine Advocate, one of the most creative producers of Bolgheri

The American magazine Wine Advocate has published Monica Lerner's opinion on the latest vintages of DOC Bolgheri wines. You can find the article at the link below but, since it is readable only for subscribers, here is a quick guide.

Thanks so much to Monica Lernet and her staff!

We are very happy that we are defined as the most creative producers of Bolgheri. The adjectives he uses most for us (and our wines) are: "crazy", "unusual", "different from its peers", etc. It really seems strange to us to pass for "bizarre" because we are among the few winemakers that yet produce wines according to ancient Italian wine traditions. Any way, everyone has their own point of view! Absolutely, we pride ourselves on making wines that are recognized as non-trivial (or obvious).