“Where could we better start if not from the vine, compared to which Italy has such an undisputed supremacy, that it gives the impression of having overcome, with this single resource, the wealth of every other country, …?” Pliny

In addition to Pliny, Horace also says that the Romans considered viticulture as one of the nation’s greatest economic resources. Cato places it in first place among the more profitability crops. We are not surprised: Italy is a great land for the viticulture and has a great production still today.

You will think: what can be said of Roman viticulture that has not already been already said and repeated?

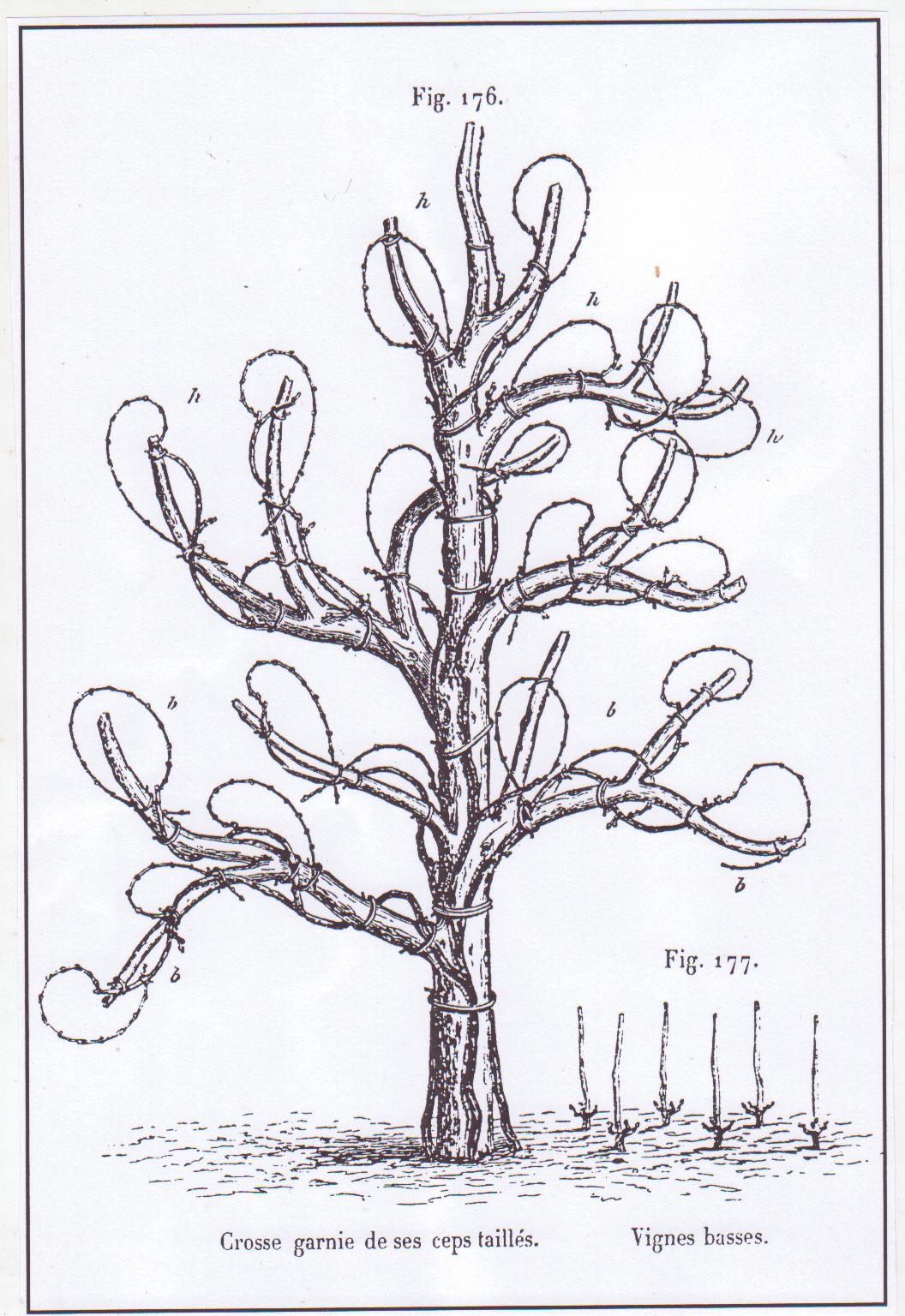

In truth, Roman viticulture has often been misrepresented due to linguistic and cultural misunderstandings, although it has been well described by Latin authors (our sources: see here) and examined far and wide by scholars of all centuries. This fact has often prevented from understanding its original and absolutely distinctive trait: the cultivation of the vine “married” to the tree (or vine training system to a tree) of Etruscan origin, a form that will remain in Italy until the first half of the twentieth century. This cultivation system was also present in other ancient civilasations but in Italy it has played a particularly important and lasting role for millennia.

Viticulture in Rome, as for almost all Italic peoples, is very ancient. Ever since man stepped our lands, he has always collected wild grapes in our Mediterranean woods. In Rome, the transition to advanced viticulture seems to have occurred due to Etruscan influence. I have already written in more detail here on the origins of viticulture in Italy.

The original Roman viticulture was therefore the same as for the Etruscans, a training system based on the natural way of wild-vine growth. In the woods, in fact, it uses trees as a support to reach the light. In Etruria maples were mainly used, in Rome mainly elms. In Latin, this cultivation system was called arbustum vitatum (vine trained-system to a tree or alberata), with the vitatum often omitted. More poetically, the term vitis maritae was also used, “married vine” (vine married to a tree). I have already described these aspects in more detail here.

If we want to imagine the classic agricultural landscape of the Roman era, we must think of a countryside with vines married to trees, arranged in rows or quincunx (like the number 5 on a dice), with intermediate strips of wheat (or other crops). There were also the olive trees.

This agricultural world is not so distant from us, even if forgotten today. Still at the beginning of the twentieth century, Chianti wine was produced by a very similar model of viticulture, well represented in this work by Raffaello Sorbi (1893): vineyards with “married vines” (system called “testucchio” in Tuscany, at the time), alternated with strips of wheat (or other crops), managed by farmers in sharecropping. The oxen with the muzzle were also identical (Pliny also recommends it, you will see).

Rome will incorporate the Greek viticulture training-system only later: the low vine cultivation system, without support or with a “dead” support (the pole), then carrying on both.

Lost in translation.

I refer to the title of a well-known film from several years ago, “Lost in translation”, which gives a good idea of what happened with the viticulture of ancient Rome, often misrepresented due to translation and cultural problems.

Unfortunately, it is also our fault. Modern Italy wine world has not paid much attention to its immense historical and cultural heritage, often with a superficial approch. Often the narration of the history of wine (including ours) in the modern era has been left to foreign authors, unrelated to our culture, who did not have sufficient instruments to understand it.

Roman viticulture has therefore often been identified only with the Greek vine-training system, the low vineyard. Scholars or popularisers, unrelated to Italian culture and / or without in-depth agricultural skills, did not even know the existence of the “married” vine. Others have considered it absolutely secondary, a primitive form of little interest, soon supplanted by Greek vine training-system, considered more advanced. Whenever the term vinea (vineyard) was found in the Latin authors, it was assumed that it referred to the low vineyard. Hugh Johnson, for example, cites the existence of the “married” vine, but he writes that “the ancient authors never talk about it” (!).

The Latin term specific to the alberata or “married” vine, arbustum, has been widely misunderstood. English authors often have translated it as a plantation of trees or woods or grove, so French ones, as Apollinaire (bouquet of arbre), and various German writers (Jungholz). They did not notice the absurdity to translate Varro’s works, for example, writing that a “grove” produces certain quantities of wine and wheat!

Latin poets wrote about the “married” vine, too, never about the low vineyard. Catullus was the first who describes the vine and the elm as wife and husband (in the Carmina). In the Augustan era, this system is often cited by Virgil and Horace. The one who talks about it most is Ovid, who frequently uses the “married” vine as a metaphor for love in Amores, Fasti, Heroides, Tristia and Metamorphoses, in the Vertumnus and Pomona’s tale (see here).

As previously mentioned on the origin of viticulture in Italy (here), there have been several multidisciplinary studies (between archeology, linguistics and viticulture) in recent decades that have tried to shed more light on our viticultural origins. Above all it the work of Paolo Bracali (University of Perugia) has clarified the meaning of the Latin terms related to the vine and their change during the long Roman history.

Vinea or arbustum?

Cato, the first of the agrarian Latin authors, is quite clear when he writes that to make a good vineyard it is necessary “that the trees are well married to the vines and that they are in sufficient numbers“. The Roman vineyard, from its origins and still in Cato’s time, was made only with vines married to trees. He indicates it with the generic term vinea (vineyard) or, when he wants to underline the form of cultivation, the more specific word arbustum.

[one_third][info_box title=”” image=”” animate=””]*Cicero tells the story of Attus Navius, a young pig guardian with divinatory skills. One day he lost a sow in a vineyard and he vowed to Jupiter, if he found it again, to offer him the largest bunch. So, it happened and, to fulfill the vow, he divided the vineyard into different parts and interpreted the flight of birds for each one, according to the divinatory Etruscan uses. In doing so, he found a cluster of incredible size and beauty to be given to the god. The young man then became the official augur of the first Etruscan king of Rome, Tarquinius Priscus.

This myth is considered at the origins of the Roman rite of the auspicatio vindemiae. Before the harvest, Flamen Dialis, the high priest of Jupiter, offered the god a bunch chosen from a public vineyard. The rite served to ensure a good harvest and was the official start at the time of the harvest. So, the period of this rite varied every year. [/info_box][/one_third]Until the late Republican era, therefore, whenever the word vinea is found, it refers only to the vine planted with trees, the traditional form of Roman viticulture. Many of these authors do not explain how the vineyard is made, they have no agronomic intent, but we can also notice it from some details. Cicero, for example, tells a myth in which a boy brings pigs into a vineyard *. It can only be a vineyard made with “married vines”, since it is practically impossible to think to graze pigs in a low vineyard with ripe grape (they would have eaten it!).

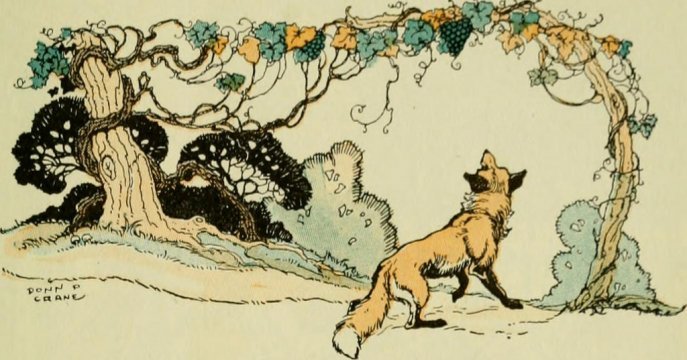

Phaedrus, who translates and readapts Aesop’s fables in the first century BC, uses the term vinea alta (tall vineyard) in the famous history of the fox that cannot reach the grapes. A change is beginning. He still uses the word vinea in the ancient way, but he feels the need to add the alta (tall) adjective. Maybe, is he afraid of not being understood?

In fact, Rome had now annexed several territories that had been Greek colonies, in the south of Italy, where the vines were cultivated low, without a support or sometimes supported by a stake. This other cultivation system also became part of Roman culture. The need not to confuse them led to a linguistic change that seems to be fixed in the last decades of the first century BC.

Varro seems to be the first to use two distinct names to indicate the two cultivation systems. From then on, in Latin texts, the word arbustum remained to indicate the “married” vine system, while vinea became the preferential term for the Greek low vineyard. The vinetum (vineyard) included both, as well as sometimes vinea (… just to not make it too easy …).

So, you understand the difficulty? It was easy for inexperienced translators (on viticultural aspects) to get lost, especially by mistaking the arbustum for a grove, not even realizing that they were talking about a vineyard.

Today in Italian, vinetum is become vigneto, vinea is become vigna. They are synonyms, both of them means “vineyard” (in general). The arbustum vitatum is become vite alberata. But this vine-training system disappeared almost completely in Italy in the mid of twentieth century and today very few Italian people remember it.

Tall or low vineyard?

From the late Republican Era and especially in the Imperial Epoc, therefore, both forms of viticulture were present.

In many texts of wine history there is a schematic subdivision according to which the low vineyard was typical of the large slave villae (the big estates) with an intensive and higher quality production. The arbustum is relegated to more primitive or less specialized contexts. In truth, this interpretation seems to reflect a twentieth-century concept of viticulture rather than an understanding of the historical epoch.

The studies of the last decades, in fact, have led to reconsider this model. The concept of specialization and intensive cultivation in Roman times was different from the modern one. Promiscuous agriculture was prevalent even in large villae. Furthermore, the presence of one or another form of viticulture seems to respond more to the cultural tradition of the place than to the estate dimension or the quality of the wine (with due exceptions), as witnessed by Virgil, Pliny the Elder and many other authors.

For example, Pliny the Younger (nephew of the other Pliny) had large properties in the upper Tiber valley, which earned him huge profits thanks to the sale of wine in Rome. Pliny says that his farmers used to cultivate “below and above“, where “above” means the “married” vine and “below” cereals, in line with the oldest local tradition. Pliny, telling of his activity as a lawyer, uses this agricultural metaphor that testifies to promiscuous agriculture: “As in agriculture I do not cultivate only the low vineyard (vinea), but also the tall one (arbustum), and not only the “married” vines (arbustum) but also the fields and in the same fields I not only sow spelled or wheat, but also barley, fava beans and other legumes, so in the discussion of a lawsuit, I broadly use different topics as if I were sowing, to harvest what will be born “.

There could therefore be been some variability in the vineyard choices. However, the prevalence of local tradition is also demonstrated by the fact that the most ancient wine-growing cultural frontiers remained more or less the same, in Italy, from ancient times until the twentieth century, as emphasized by most of the Italian agricultural historians. Generally speaking, the “married” vine remained predominant in central and northern Italy, where the Etruscan tradition had arrived in the past, including neighboring peoples influenced by them. The low vine remained prevalent in southern Italy, where there was the ancient Greek viticultural culture. (see here)

In modern interpretation, the “married” vine has often been linked to the production of a poor-quality wine. The Romans, however, didn’t think so. Pliny the Elder testifies that the most renowned wines of his time, the famous wines from Campania, capable of very long aging, derived precisely from “married” vines.

He is an advocate of the “married” vine compared to the low vine, as well as Columella. The Latin authors list a series of advantages, the same cited by Italian authors till the beginning of the twentieth century. Numerous subsequent Italian historical and literary sources, from the Edict of Rothari (645 AD) to the nineteenth-century works, indicate the “married” vine as the most suitable for the economy of the farm and the interests of the owner.

He is an advocate of the “married” vine compared to the low vine, as well as Columella. The Latin authors list a series of advantages, the same cited by Italian authors till the beginning of the twentieth century. Numerous subsequent Italian historical and literary sources, from the Edict of Rothari (645 AD) to the nineteenth-century works, indicate the “married” vine as the most suitable for the economy of the farm and the interests of the owner.

The grapes, kept away from the ground, were more protected from frost and humidity. The branches of the tree protect (in part) grapes from other adversities, such as hail. Furthermore, it was considered a considerable advantage to be able to exploit the same plot of land for multiple uses. The cultivation of wheat, or other crops, is easy between the rows of the tall vineyard. Animals can be grazed there for most of the year, without risks for grapes or sprouts (unless there were other crops in the middle to protect). At the time, it was common for the owner to rent the pasture also to external shepherds. In the low vineyard the pasture was possible only during the period of vine rest. In addition, the “married” vine had no need of fences and hedges, being the grape more protected even from wild animals. Only large livestock is dangerous for tall vineyards. In fact, Pliny recommends putting muzzles to oxen when plowing the soil.

When Cato makes his famous ranking of economically most interesting crops, he reminds us that the “married” vine gives double profitability. In fact, he puts it in first place as grape production, but it also returns to the eighth place thanks to the support trees: the leaves as fodder, the pruning of the branches like firewood, the fruits in case of utilize of fruit trees (Cato often mentions the use of the fig tree). This passage was one of the most misrepresented: the vinea in the first place was interpreted as a low vine and the arbustum, in the eighth place, as a grove.

There are not only advantages. The Romans themselves recognized the difficulty of the vineyard works. Pliny tells that, at the origins, King Numa Pompilius introduced the obligation of pruning vines, but the Romans did not want to climb trees, even very tall, for fear of falling. Since then, the use of guaranteeing the funeral expenses to the vintners was introduced in the employment contract. Aside from the myths, Columella cites the Saserna family, owners in the Cisalpine Gaul, who found this system too expensive.

In the following centuries (especially in the nineteenth century) the dispute, that will divide the experts between detractors and supporters, will continue. Several negative aspects have been recognized such as the shading of the vines, the competition between the two species (in not sufficiently fertile soils) with the production of poor body wines, the slowness to achieve an optimal grape production, pruning and higher harvesting costs, the impossibility of even a minimal mechanization, … The plant disease called graphiosis contributed to abandon this traditional form in the 20s of the twentieth century, causing the death of most of the elms. Simply, there wasn’t more space for the “married” vine in the modern specialized viticulture. The peasant ancient world was already sunset.

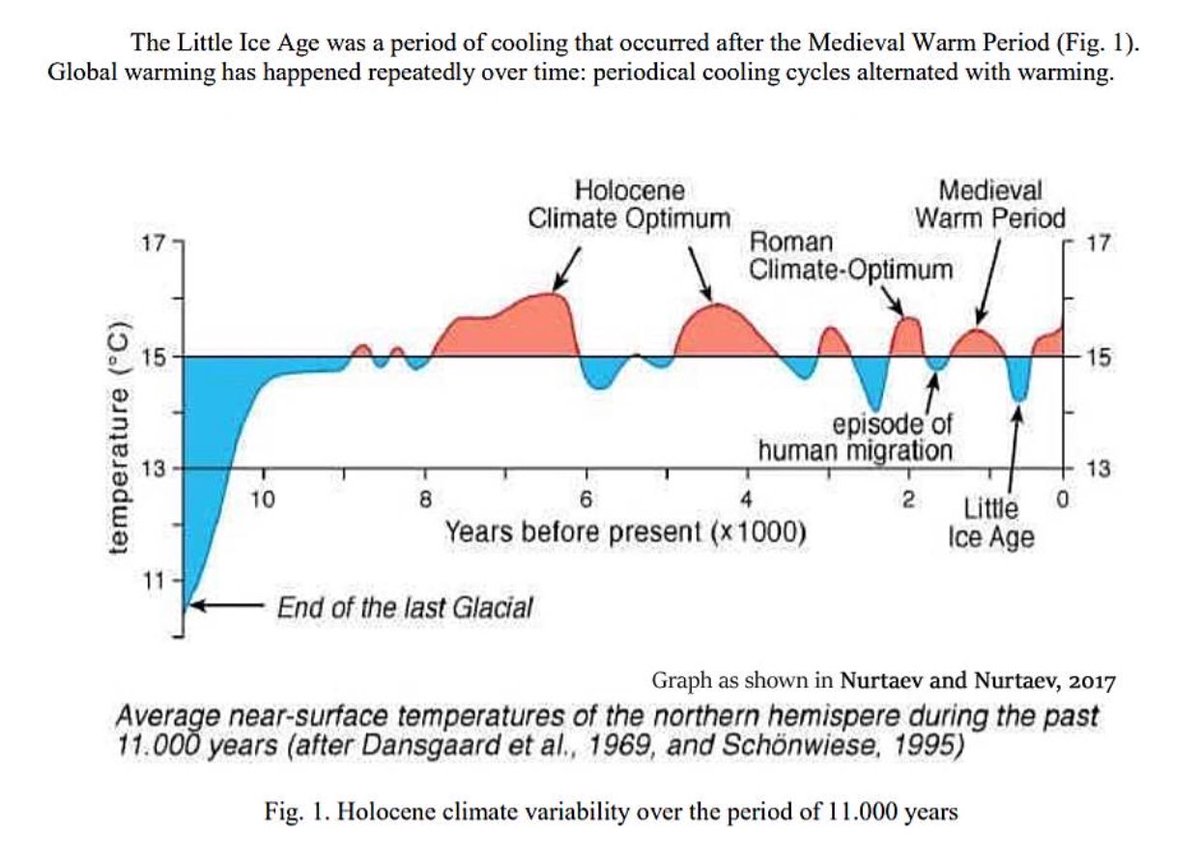

Finally, I would like to remind you that the Roman era, especially in the Imperial phase, was characterized by a very hot climatic period. Today, with the changes in the climate going on, we have already realized that we need to review the production balance of just twenty-thirty years ago. We cannot exclude a priori that a high-producing viticultural form, if well managed and in the appropriate climate and soil, cannot however produce good quality wines. We must remember that Columella testifies how, at the acme of their viticulture, the Romans had a clear understanding of the concept of the link between productive balance and wine quality. This aspect will be “rediscovered” only several centuries later.

Finally, I would like to remind you that the Roman era, especially in the Imperial phase, was characterized by a very hot climatic period. Today, with the changes in the climate going on, we have already realized that we need to review the production balance of just twenty-thirty years ago. We cannot exclude a priori that a high-producing viticultural form, if well managed and in the appropriate climate and soil, cannot however produce good quality wines. We must remember that Columella testifies how, at the acme of their viticulture, the Romans had a clear understanding of the concept of the link between productive balance and wine quality. This aspect will be “rediscovered” only several centuries later.

The “married” vine around Europe (and more).

I have already written about the long “career” of the vine married to the tree in Italy (here). One of the great contribution of Rome was to have spread viticulture in other parts of Europe, through its legionnaires. It was taken for granted that it was only the low vineyard. In reality they also spread the “married” one. In fact, there is a trace of it in the viticultural history of other European territories.

I also remember that other systems of tall vine growing, with poles or pergolas, were always spread by the Romans. They are still present in many parts of Europe.

There are several traces of the ancient “married” vine tradition in France. The tall vineyards (in general) are called hautains. The “married” vine was present in the Middle Ages in numerous territories, for example in Picardy or in Provence (on walnut trees). In the 14th century, there are documents demonstrating its spread to Avignon. Olivier de Serres in “Le théâtre d’agriculture et mesnage des champs” still testifies to its presence in the seventeenth century, especially in Brie, Champagne, Burgundy, Berry, Dauphiné (on cherry trees), Savoy and in the Rhone valley. Until the beginning of the twentieth century, they could still be found mainly in Haute-Savoie and in the area of the western Basque Pyrenees. It disappeared completely after the phylloxera crisis.

In north-western Portugal, the tradition of the tall vineyard still remains, with poles but sometimes still the real “married” vines, with the name of viña de enforcato, in the production area of the vinho verde.

In Spain the “married” vine has not left traces in the viticultural tradition, although we know that it was brought there by the Romans. In particular, there is direct evidence from Columella, who introduced it in its properties in Baetica. Today, there are only other forms of tall vineyards in Galicia and the Basque country.

The very ancient cultural imprint has remained at least in a widespread proverb, which says: “no se le pueden pedir peras al elmo“, “you cannot ask the elm for pears”, also quoted by Cervantes in Don Quixote. In Portugal there is a very similar one: “Não pode o ulmeiro dar peras“, “the elm cannot give pears”. Both of these proverbs have the meaning of asking for something that is impossible, but most Spaniards and Portuguese do not know why they’re speaking on elms and pears. The proverbs origin most likely is found in the Sententiae of Publius Syrus (1st century BC), who writes: “Pirum, non ulmum accedas, si cupias pira“, “you should go to a pear-tree for pears, not to an elm”. The ancient Romans understood it easier: the elm was the favorite “husband” of the vine, so he certainly could not give pears but grapes.

If the Spaniards abandoned the “married” vine in their motherland, they took it to the New World during the Conquista (the Spanish colonization of the Americas) with other forms of tall vine-training systems. They needed wine for Mass, so they planted vineyards wherever they went. They also had succeeded in Bolivia, in the Cinti valley, at an altitude of 1900-2550 meters above sea level, where it was really difficult for growing vines. Yet they solved the problem by “dusting off” ancient Roman knowledge, with vines married to indigenous trees, even very tall ones, the only way to preserve shoots and grapes in that so difficult climate.

If you want to see a “married” vine, come at Guado al Melo estate and visit our little ancient vineyards.

(…continued..)

Bibliography:

Paolo Braconi, “Vinea nostra. La via romana alla viticoltura”.

Paolo Braconi, “Catone e la viticoltura intensiva”.

Paolo Braconi, “In vineis arbustisque. Il concetto di vigneto in epoca Romana.

Paolo Braconi, “L’albero della vite: riflessioni su un matrimonio interrotto”.

P. Fuentes-Utrilla et al., “The historical relationship of elms and vines”, Invest. Agrar.: Sist. Recur For (2004) 13 (1), 7-15

Attilio Scienza, “Quando le cattedrali erano bianche”, Quaderni monotematici della rivista mantovagricoltura, il Grappello Ruberti nella storia della viticoltura mantovana.

Attilio Scienza et al., Atti del Convegno “Origini della viticoltura”, 2010.

Luigi Manzi “La viticoltura e l’enologia presso i Romani”, 1883.

Dalmasso e Marescalchi, “Storia della vite e del vino in Italia”, 1931-1933-1937.

Emilio Sereni, “Storia del paesaggio agrario italiano”, 1961.

Enrico Guagnini, “Il vino nella storia”, 1981.

Hugh Johnson, “The Story of Wine”, 1991.

Valerio Merlo, “Contadini perfetti e cittadini agricoltori nel pensiero antico”, Alce Nero.

Roger Dion, “Histoire de la vigne et du vin en France, des origines au XIX siècle”, Parigi, 1959.

https://fr.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hautain