The main part of the wine charm is represented by its aromas. I’ll tell you how they are born and how it is possible a so high diversification of them.

(cover picture from Isak S. Pretorius, 2017 Critical Reviews in Biotechnology, 37:1, 112-136)

How many are the wine aromas? It has an incredible aromatic richness and diversification. Some wines are more simple, with few perfumes. Some others have an amazing complexity. Each wine is not identical to another. You can also find difference between wines from the same area or produced with the same grape varieties.

How is such a great complexity and diversification possible?

“Strawberries, cherries and an angel’s kiss in spring

My wine is really made from all these things”

(Summer Wine, by Nancy Sinatra)

Oh, oh summer wine / Strawberries, cherries and an angel’s kiss in spring / My summer wine is really made from all these things / Take off your silver spurs and help me pass the time / And I will give to you summer wine / Oh, oh summer winee“

I will now try to explain how the aromas of wine come from the vineyard and reach the bottle. Above all, I will try to make you understand where all the aromatic diversity that wine can express comes from, how it is possible to enhance it in production or, vice versa, lose it.

In the following boxes there are some simple basic information on aromatic molecules and the smell, also useful for understanding some specific terms that are very often used in the world of wine. Immediately after, we will enter the heart of the scent of wine.

Today, thanks to increasingly sophisticated analysis techniques, we have come to define hundreds of aromatic components in wines from a chemical point of view. The aromatic molecules, that is the substances responsible for perfumes, are of many different types. However, they have in common the ability to interact with our olfactory receptors, located in the nasal cavity. Their aromaticity depends on the fact that they are volatile, that is, they have a marked tendency to pass from the liquid to the gaseous state. They are able to reach our olfactory receptors, using two ways. They can pass through the nose when we smell. They can also reach them from the mouth, when we have wine in the oral cavity, through the retro-nasal passages. About wine, we call aromatic profile the entire range of aromas that it expresses.

Why is the nose (of expert people) still the privileged tool for making certain decisions in wine production? It is not easy to trace to the aromatic profile of a wine starting from the chemical analysis, because the aromatic expression of these molecules is not always easily predictable. Some of them are perceptible only above certain concentrations, others are dominant in the profile even if present in little more than traces. Some change the type of aroma depending on their concentration or can even become unpleasant. Certain aromatic compounds have a synergistic action: if they are present together, they give a different smell. Not only that: the studies done so far have shown that it is very difficult to predict the volatility of an aromatic molecule in a complex mixture (such as wine). The volatility of a molecule is influenced by the others. Even the non-volatile part of the wine (made up of polyphenols, polysaccharides, glucose and other substances) has an influence on the volatility of the aromatic component, in a way not yet fully understood.

Smell is an incredibly complex and very powerful sense. We have about a thousand different types of olfactory receptors. Each aromatic molecule activates a different combination of these receptors. Therefore, considering a potentially infinite combinatorial possibility, our nose can recognize a very high number of odorous substances. But it also has a very individual component. First of all, our individual olfactory capacity is influenced by genetics. This not only means that someone is more gifted than others, but also that different people can perceive sensations differently. Furthermore, important psychological factors also are present. Linking an aromatic sensation to a name (rose, strowberry or other) gets involved our olfactory memory, that is the memory of having already smelled a similar sensation and having classified it with that name. In a complex blend like wine, the aromas are not always clear and defined. The associations we can make are therefore not unique: we connect a certain odor sensation to the one that is most similar in our memory. Hence, this connection can vary depending on our experiences. Surely, people who are more used to smelling perfumes have an olfactory memory that is more trained to recognize and denominate certain sensations. Furthermore, the numerous studies carried out so far have also shown that our olfactory capacity is influenced by the situations: by the mood of the moment, by our (unconscious or not) prejudices and expectations, by the suggestion created by other people, … For all these reasons, in sensory analysis researches (where the tasting is not for pleasure but to try to describe a wine in the most objective way possible), the tests are made by groups of people, organizing them and examining the results according to statistical evaluations.

Given that there is an rilevant individual component, people that drinks wine for pleasure should not feel in awe of freely expressing his sensations. If you want to improve your smell capacity, it’s not that difficult. It is enough to train yourself often, smelling single aromas (fruits, aromatic herbs, spices, etc.), so that they are marked in your olfactory memory.

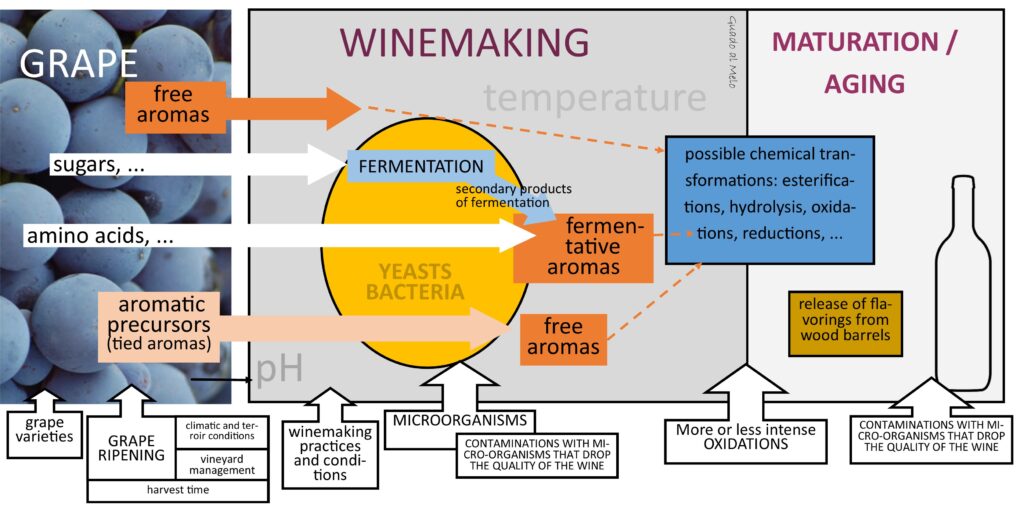

How the wine aromas are born

Hearing about peach or rose or berry scents in wine, inexpert people often ask if these aromas are added during wine production. The answer is that there is no need: all the aromas of wine originate from grapes and winemaking process. Adding flavorings could be a shortcut. In Italy, this practice is prohibited by law.

How then is it possible that wine can smell of peach or rose (or many other things)? It is possible because the molecules that give these aromatic sensations are common among the different species of the plant kingdom. In this context, the grapevine (Vitis vinifera L.) is decidedly particular: it has a very large potential aromatic richness. Throughout history, this characteristic has made grapes the queen of raw materials with which to produce a fermented drink.

However, the grape itself does not have many smells. There are some grape varieties more fragrant than the others, which are defined as “aromatic”, such as different Moscato. Most of the aromas we can find in the wine derive from grape but they are molecules that are in a non-odorous form in the fruit. They are called aromatic precursors. They are not perceptible to the smell because the aromatic molecules are linked with others that prevent their volatility. They can become volatile only if this bond is broken. That can occur during winemaking, as we will see.

The varietal aromas are numerous. We can group them into 4 families which, as mentioned, are widespread in the plant kingdom, so they give aromas that recall other plants, fruits and flowers:

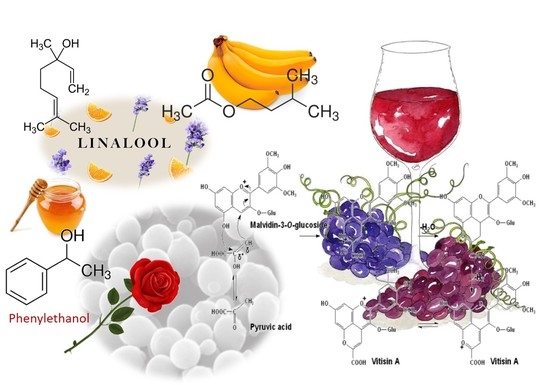

- a very extensive family is that of terpene compounds, which give aromas of rose, linden, lily of the valley, lemongrass, … but also that composite sensation of “muscat”;

- carotenoids derivatives, which give complex aromas of flowers, exotic fruits, apples, violets, tobacco, tea, berries, …;

- metoxypyrazines, which give notes of green pepper, asparagus, earthy hints;

- thiol compounds, they can contribute in several cases to the notes of cassis, passion fruit, broom, tomato leaf, peach, eucalyptus, … They also develop in fermentation, where they are often responsible for bad odors.

Some aromatic molecules can develop when the grapes are pressed: they are called prefermentative aromas. The most typical example are aldehydes, which give hints of cut grass (not very pleasant). When the grape is mashed, some enzymes come into contact with the bloom, the waxy material that covers the berry peel, and transform it. The stronger the mechanical stress to which the grape is subjected, the more these substances originate. In reality, today they are much less important than in the past: it is now common to use crushing or pressing machines that act very softly.

Mainly, other aromatic molecules are formed by the action of yeasts and bacteria during fermentation reactions, as secondary products of the process. Other aromas are produced by the microorganisms by other metabolic pathway, starting from substances that are present in the must / wine (especially amino acids). All these aromas are called fermentative. All together, they represent the specific aromatic base of the wine, that “vinous” sensation that makes us understand that we are smelling wine even with closed eyes. This aromatic core, which prof. Ferreira of the University of Zaragoza defines a “vinous matrix“, it is a set of heterogeneous compounds. It includes higher alcohols (“vinous” notes), ethyl esters of fatty acids (honey, wax, different floral aromas, …), acetic esters of higher alcohols (banana, apple, candy, rose), volatile fatty acids (acetic acid, …). So far, 27 have been identified. In each wine they can be different in presence and quantity. Ethyl acetate, the most important ester in wine (but also the least positive) is responsible for the notes of acescence (not acetic acid, as is often believed). It is produced by yeasts in fermentation in small part. At low doses, it seems to contribute positively to the aromatic profile. When it is more, it almost always derives from contamination of acetic bacteria.

I have described to you what is the basic core of wine aromas. Then, other modification can occure that can enrich or alter the wine profile. Malo-lactic fermentation, mainly carried out by the bacterium Oenococcus oeni, leads to the formation of other fatty acids and esters, which can give a buttery smell. During winemaking and aging, other chemical reactions can occur which act on aromas and modify them: esterifications, oxidations, reductions, hydrolysis, etc. Some wine containers may release aromas (expecially new oak barrels or if you add wood chippings) or can create conditions that favor oxidation (concrete, amphora). If the aging is done on the lees, there are typical aromas of bread crust or yeast. I will not enter now in the very complex part of what are defined “olfactory wine defects”, which we will talk about another time.

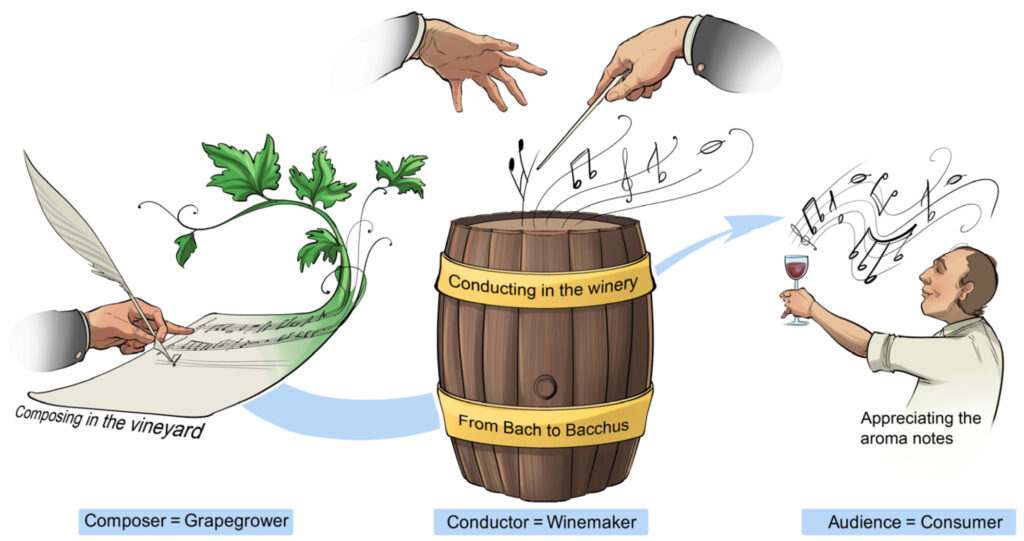

In general, the aromatic profile of wine is based on the vinous matrix on which the aforementioned varietal aromas are grafted. All these aromas integrate with each other like the instruments of an orchestra, in a complex relationship between them and with the non-volatile component of the wine, which modulates the olfactory expression.

Why is there such a large differentiation between wines?

Most of the varietal aromas accumulate more or less progressively during the ripening of the grapes. The metoxypyrazines, on the other hand, follow the opposite path: they are highest in the small green berry and are demolished during the ripening. We can therefore understand that the conditions in which ripening takes place (the terroir, the climate, the vintage, the choices and cultivation practices) can change the internal balance of the fruit, influencing the aromatic components. It is therefore confirmed that the quality of the grapes is truly fundamental for a great wine. Poor, poorly grown, unhealthy grapes, etc. they will never give great products. Likewise, the decision of when to harvest is important. If the harvest is done before or after, different aromas are obtained. For example, the hint of green pepper is often described as typical of Cabernet sauvignon, but is only partially true. The content of methoxypyrazines, responsible for this aroma, becomes important in wine if grape is harvested too early. The methoxypyrazines are also influenced by environmental conditions: it is easier to find them in wines of cooler climates than in warmer ones with high solar irradiation (where they are degraded much faster).

The aromatic precursors, as mentioned above, are released during the winemaking. Therefore, there is a reserve of potential aromas in the must that is derived from grapes, but it is not automatic that they’ll be expressed in the wine. They can be expressed or not, in whole or in part, depending on the winemaking (and the subsequent phases) conditions and practices. These conditions also influence the fermentative aromas, the vinous matrix I mentioned above.

There are many studies on these aspects. It has been showed that various elements influencing yeast activity can modify the aromatic component of wine. Among them, I remember the presence and composition of some important nutritional factors, essential to yeasts as sources of nitrogen and vitamins. An influence is also due to the pH and to the temperature. Nutrients and pH depend on the qualitiy of grape: if it ripened with optimal conditions, the managment of the vineyard, the moment of harvesting … It is possible to add additives to adjust these elements, but it is an industrial approach, that does not enhance the identity of the grape varieties and territory. The pH can vary in other ways, for example by the presence of some microrganisms. In the past, it was frequently modified by the release of substances from concrete containers.

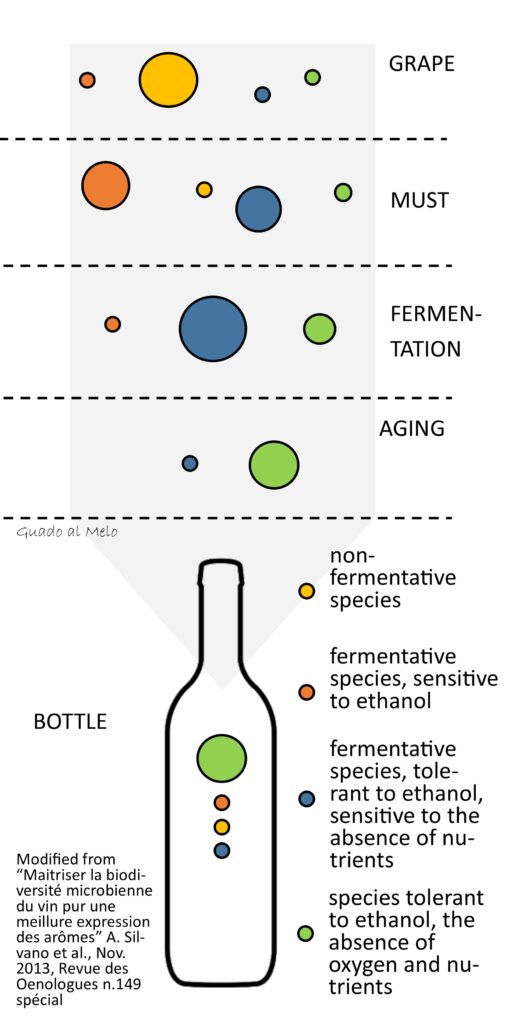

Another important element in modifying the aromatic composition of a wine is represented by the type of microorganisms (yeasts and bacteria) that are present. Each type (species and strain) produces different quantities and proportions of the fermentative aromas. Therefore, the higher the biodiversity of yeasts, the more complex wine is. However, let us remember that all these elements are connected: for example, if we have a high biodiversity of yeasts but poor quality grapes, there will still be no aromatic complexity. However, the microorganism pool need to be managed carefully, to avoid the presence of those that have a negative action for the wine. I would like to underline that in any case no pathogenic microorganisms for humans survive in wine, due to its acidity.

As I have already told in a previous article (here), a heterogeneous group of microorganisms goes into the must: they derive from grapes, harvesting tools and the cellar. The group changes with the territory, the climatic conditions, the insolation, the different variety of vines, the management of the vineyard and the cellar, … Actually, most of these microorganisms die in the passage from grape to must. There are very different conditions with respect to the surface of grapes or objects: there is no oxygen, there is a very high sugar concentration, the temperature changes, etc. During fermentation, the conditions change again and the populations of the microorganisms yet change. Above all, those who suffer from the progressive increase in alcohol succumb. Some strains also have the ability to produce substances capable of eliminating competition. We know that Saccharomyces will become prevalent in conducting fermentation. However, non-Saccharomyces, both in the initial stages and when they become secondary, can enrich the must with metabolites that contribute positively to the wine’s aromatic profile, expanding its complexity. In the figure below, the microorganisms indicated with the green dot are negative, which you would never want to have in your cellar, much less in the final bottle.

It is possible to schematize the different groups of microorganisms in 4 families, according to their behavior:

- Non-fermentative microorganisms: these are those prevalent on the grape skins but which decrease significantly with mashing (e.g. species of Cryptococcus, Rhodotorula, A. pullulans, various species of Serratia, etc.)

- Fermentation species but with low tolerance to ethanol (alcohol): they increase in the must and participate in the initial stages of fermentation but then, they decrease with the progressive accumulation of alcohol and for other reasons (different species of Candida, Pichia, Lactobacillus, G. oxydans, etc.)

- Fermentative species, which tolerate the accumulation of ethanol. At the end of the processes, however, they decrease because they suffer from a lack of nutrients (Saccharomyces cerevisiae, Oenococcus oeni, …).

- Species resistant to the absence of nutrients and to sulphites: some microorganisms can remain in high numbers even after the end of fermentation because they can feed on other compounds and can also resist the addition of sulphites in bottling. Among these, there are some very dangerous ones, such as Brettanomyces bruxellensis, which causes really unpleasant smells (smell of stable, horse, etc.).

The understanding of these mechanisms has also led to the selection of yeasts that allow to change the aromatic profile of the wine, both for commercial choices and to make up for production / technical deficiencies (poor quality grapes, mistakes, etc.). In this way, however, wines that do not express the particularity of their genius loci (the spirit of the place, or terroir) are produced. They can be quite good, but similar to many others that have been produced with the same practices. They are generally simple wines, with very few aromas, according to a serial production that is the same every year.

If you have followed me this far, you will have understood how nature gives us a complexity that we humans can hardly equal. With interventions that we believe are improving, we actually reduce this wealth to the few elements that we can control. When you hear about artisanal wines, natural wines or other similar definitions, we are talking about that: winemakers who try to preserve all the peculiarities of their vineyard to the maximum and enhance it in their wines.

However, it is not easy to make a wine by managing all this complexity and being able to obtain good / great results. Mistakes or wrong management from the vineyard to the cellar can give rise to simple, mediocre or even unpleasant wines. Here lies the artisan value of the wine. Managing a vineyard and making wine are jobs that require a lot of knowledge, as well as a great deal of experience and a certain degree of talent. In other words, a great deal of professionalism is needed. Unfortunately, today this last word is definitely underestimated: sometimes, improvisation arouses more sympathy or is (erroneously) associated with something more “genuine”. Knowledge does not necessarily imply more disruptive interventions on wine: it is often the opposite. The expert winemaker understands how to work well in subtraction, not in addition.

A common metaphor (but that gives a good idea) is the one that associates the birth of wine with music. The grape is the composer, even if I would also add the territory, the vintage, the microorganisms, etc. All these elements are directed by the winemaker, like an orchestra conductor, who knows how to get the most out of each one but, above all, manages to make them work well together. (picture from Isak S. Pretorius (2017) Synthetic genome engineering forging new frontiers for wine yeast, Critical Reviews in Biotechnology, 37:1, 112-136, DOI: 10.1080/07388551.2016.1214945)

In conclusion, the birth of the wine aromas is a kind of magic, which depends on an inseparable union: nature (the grape, with all its differences linked to the territory and vintage) and man (with his work, culture, traditions and choices, as well as his ability), as the poet wrote:

"Drink it, and remember in every drop of gold, in every glass of topaz, in every spoon of purple, that autumn worked for to fill the vessels with wine; and, in the ritual of his work, the simple man has learned to remember the land and his duties, to diffuse the canticle of the grape.

(Pablo Neruda, Ode to Wine)

Bibliography:

Trattato di enologia, P. Ribéreau-Gayon et al., 2013, Edagricole

Aromes des vins, Dossier spécial de la Revue des Oenologues, n.149 Nov. 2013