During the fourteenth century, another oriental luxury wine was established. Its name was Malvasia, marketed by the Venetians. It seems that the name derives from the place where it was stored, Monembasia, a port in the Peloponnese, while the production seems to have taken place mainly in Crete Island. Malvasia was even stronger, fortified and sweet wine than the previous ones (it is thought between 16 and 18 % alcohol). It became the noblest wine of the time in all of Europe. It was imitated everywhere in Italy. Hence born the legacy of the many current Italian varieties named Malvasia (black Malvasia, black from Basilicata, long black, white, long white, white from Candia, white from Basilicata, from Casorzo, Lipari, Sardinia, Schierano, Istriana , etc.). All they are not genetically related to each other. They owe their name, most likely, to the fact that they were used locally in the past to produce the same type of wine.

As written in the previous post, almost all Italian wines up to the thirteenth century were anonymous and distinguished only by color (white= album, red = vermilium, …), by flavor (dulce = sweet, bruscum =acid, …), from the area of production (vinum de plano = wine from level ground, vinum de monte = wine from the hills, ecc.). With the fourteenth century, more and more local quality wines emerged, even if they did not imitate the oriental wines. They were yet for a local consumption, at most regional. They weren’t luxurious, but they were starting to have higher prices, within the reach of medium class people. They were also the most recommended in medical treatises, which often disdained those of luxury because they were too heavy and aromatic. These wines slowly began to have a name, which could be linked to the production area or other characteristics. Among these we remember the different Moscatello, produced in various areas of Italy, Piedmontese Nebbiolo and Arneis, Ligurian Razzese, Lombard Groppello, Lombard-Venetian Schiava, Garganigo and Marzemino from Veneto, Friulian Refosco, Chianti Tuscan, Lacrima and Fiano from Campania, the southern Gaglioppo, etc. Some were a sort of local cloning of luxury wines, such as Vernaccia of Cellatica (near Brescia), Vernaccia of San Gimignano, Ribolla from Imola, Greco from Corsica, Greco from Velletri, Malvasia and Vernaccia from Sardinia.

The dawn of the modern grape varieties. There is little point in looking for current wines and varieties in the Middle Ages, even if sometimes the same names are found. There are too many centuries and many probable transformations between. The Middle Ages, like the ancient times, were a period in which wines but also a lot of varieties traveled, for the Mediterranean and for Europe, with also the possibility of crossings with local grapevines. These exchanges are recounted, for example, in “Trecentonovelle” (“Three hundred stories”) (1390) by Franco Sacchetti. He wrote that in Italy there was so much desire to produce great wines that the winemakers tried to grab the best grape varieties from all over, recovering the rooted cuttings directly or exploiting the network of contacts offered by the Church. For example, Sacchetti reports that the Florentine nobleman Vieri de’ Bardi sent off from Portovenere to his estate in Antella (Bagno a Ripoli, near Florence) some cuttings of a variety with which the famous Vernaccia of Coniglia wine was produced.

From the mid-1300s to the early 1400s, there were some important transformations which once again significantly changed the Italian wine geography.

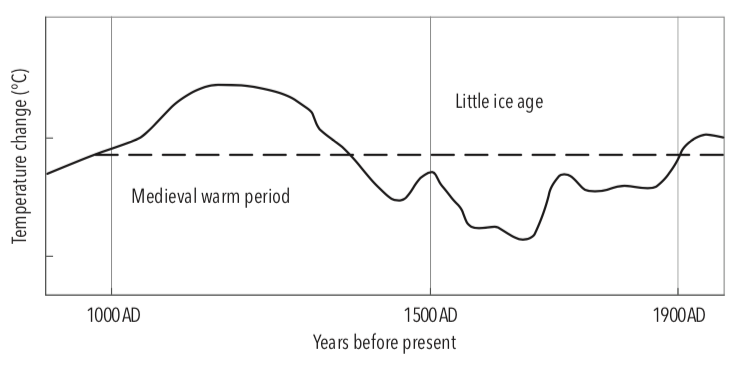

On the one hand, the climate began to worsen more and more, after the medieval warm period that had favored the boom in viticulture. That cold period called the “Little Ice Age” began, which will shock all of Europe with a general agricultural crisis. The famines contributed to the spread of epidemics such as the Black Plague which, from 1348, led to the decimation of the populations. The crisis caused the decrease of agriculture in general, including the winegrowing. Furthermore, the cold made the grape vine disappear from all those territories where the climate had now become an insurmountable limit.

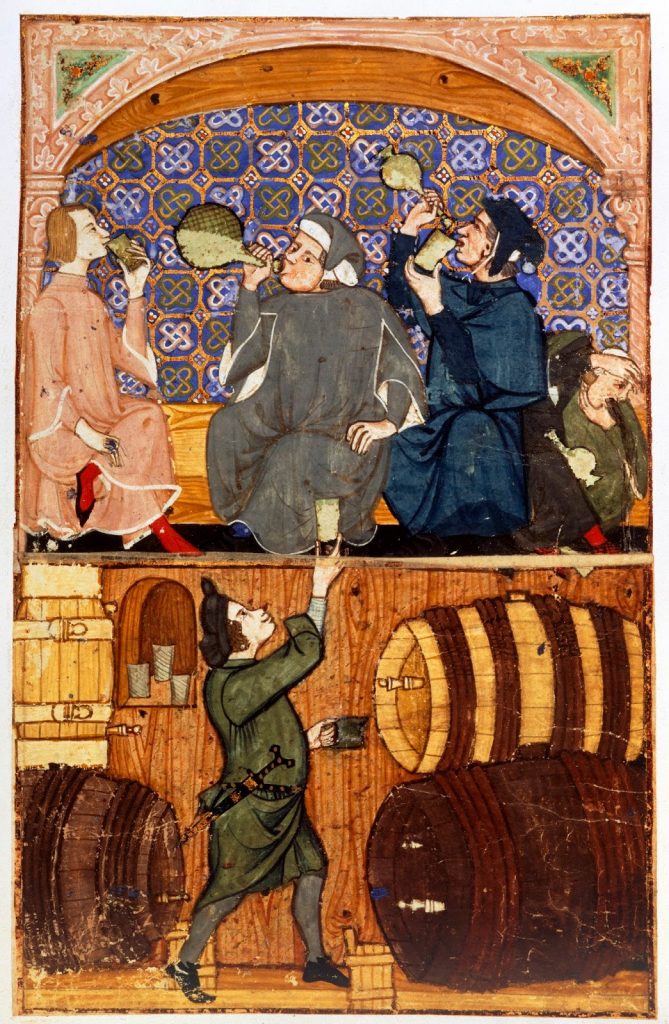

The wine between drunkenness, mockery and pleasure. The Black Plague is the background to Boccaccio’s Decameron, about which I have told so far as the greatest medieval work that talks so much about wine. The Decameron is made up of a series of short stories that a group of young Florentine nobles, seven girls and three boys, tell in turn to pass the time in the country villa where they took refuge to escape the infection. In the introduction, Boccaccio describes the beauties of this residence, including the cellars, rich in fine wines, according to him more suitable for “good drinkers than for wise and honest women“. In the Middle Ages, reputable women never must drink too much. However, at the times, the excess of wine was deplorable for everyone, both for the morals and for the health. But Boccaccio’s stories are not very moralistic, often semi-serious. Drunkenness is linked to deception or teasing, while intelligent women often manage to cunningly overcome life’s adversities.

The story of Alatiel. The beautiful Alatiel, daughter of the sultan of Babylon, is sent by her father in marriage to the king of Morocco. A long journey to the Mediterranean begins for her, during which she is kidnapped and violated by several men. The first, Pericone, thinks of making her give in with the wine. “Since he realized that she liked wine, which she was not used to because her religion prevented her from drinking it, he thought of making her surrender with the help of wine and Venus. One evening, he invited her to a party and ordered the cupbearer to serve her a glass of various wines mixed together. Having drunk the mixture, the woman, forgetting past misfortunes, became happy and seeing some women dancing Spanish dances, she too danced in the Alexandrian manner. So, she spent most of the night between wines and dances. When the guests left, the man, who was very robust and energetic, went into the room with the woman. She, warmer with wine than honesty, undressed and went to bed. ” At the end of the story, Alatiel manages to return home. At that time, all these misadventures would compromise the life of a girl. However, she manages to convince her father that she has been welcomed all that time in a convent and so she marries her fiancé.

The semi-serious history of Tofano and Ghita. The rich Tofano is very jealous of his wife, the beautiful Ghita. His torment prompts her to correspond to a young suitor. The woman starts frequently gets her husband drunk to meet her lover. One night, as she returns from a date, her husband locks her out of the house, to unmask her in front of the neighbors. The woman threatens craftily to commit suicide, telling him that they would later blame him. Then, thanks to the darkness that hide her actions, she throws a stone into the well. The worried man runs to watch. Ghita quickly enters the house and locks her husband out. Tofano starts screaming and swearing, waking up the neighborhood, while Ghita yells at everyone that her husband always gets drunk and spends the night in the taverns. Tofano’s misconduct spreads and reaches also the ears of Ghita’s relatives, who beat the man and take the woman away. Eventually, Tofano, realizing that everything had started from his mad jealousy, repents and convinces his wife to come back, leaving her free to do as she pleases, as long as discreetly.

Between the end of the 14th century and the beginning of the 15th century, there was also an epochal change in trade, called the “freight revolution“. Until then, the wine trade was limited to the most expensive products, as well as durable, because the shipping costs were calculated essentially on the basis of the volume occupied by the goods on the ship. The wine barrels take up a lot of space. Proportionately, it was cheaper to transport gemstones. The freight revolution instead introduced the use of calculating the cost also taking into account the value of the goods. The wine trade benefited greatly and, consequently, it had a very important increase.

As mentioned, until then the vine was grown practically everywhere in Italy, to have wine available for the community and, except for luxury products, the consumption of common wines was essentially local. As transportation became cheaper, more wines began to travel. The trade was also facilitated by the birth of larger political entities, which lowered the number of duties in travel and therefore the final price to the consumer. Furthermore, in the richer areas of Northern and Central Italy, there was also an improvement of the roads. So, people started to have a wide choice at their disposal. More and more, the consumption was focused on the best wines, not necessarily the local ones.

All these events contributed to once again change the Italian geography of wine. Viticulture decreased in general and, in particular, decreased or disappeared from all those areas where it is little or no suitable. On the contrary, it grew more and more in those districts considered of higher quality, where the economic performance became more and more relevant, such as Tuscany, the “Oltrepò Pavese”, the Venetian hills, Istria, the Castelli Romani area, Apulia, Calabria, Langhe, etc. The high alcohol content of oriental wines (or made in that style), obtained by drying or concentration style, was not more necessary. It was enough if a good alcohol content, derived from an area suited to viticulture, for the wines to be preserved well enough, saving their pleasantness and aromas.

As marketing increased, the need for wines to be recognizable, with precise identities, increased more and more. Till then, they spoke only of red or white wine or a little more. From now, the names of the wines began to become a common practice. They often derived from the type of product, often combined with the place of production or, in other cases, that of storage or distribution, rarely of the grape varieties. Particularly suited areas began to be mentioned more and more, sometimes even the single high-quality vineyards. For example, 106 different wine producing locations near the city are identified in the Florentine land registry of 1427.

But don’t think that there was a great clarity, like today. The situation was still very confused, both for the time and for modern scholars who tried to decipher it, because with the same name and origin there are also wines with very different characteristics (white and red, sweet and non-sweet wines, etc.). We are still a long way from a very precise and defined geography of wine. We can say that it was starting to take shape.

In the fifteenth century the consumption of wine was by now very advanced. The wines began to be distinguished and known for their organoleptic and cultural peculiarities, as well as for their combinations with food. The first cookery treaties were also born in that period.

In the mid-fifteenth century, the Byzantine Empire collapsed, Genoese trade with the eastern Mediterranean disappeared, while the Venetian one was considerably reduced. The prestige of oriental or oriental-style wines (very sweet, flavored and alcoholic) collapsed. However, their taste was not completely lost, especially in the banquets and the ceremonies. However, a new type of luxury wine was imposed, the one coming from a suitable territory, dry, not excessively alcoholic, white or red, pleasantly scented. They were young wines, as the aging processes will only be “discovered” again a few centuries later. However, we will talk more about the Renaissance another time.

… To be continued

Bibliography:

Prof. Alfonso Marini (AA 2020-2021) Dispense del corso di storia medievale.

Pini, Antonio Ivan (2003) Il vino del ricco e il vino del povero. In: La civiltà del vino. Fonti, temi e produzioni vitivinicole dal Medioevo al Novecento. Atti del convegno (Monticelli Brusati, Antica Fratta, 5-6 ottobre 2001). Centro culturale artistico di Franciacorta e del Sebino, Brescia, pp. 585-598.

Antonio Saltini (1998), Per la storia delle pratiche di cantina (parte 1) enologia antica, enologia moderna: un solo vino, o bevande incomparabili? In Rivista di Storia dell’Agricoltura n.1, giugno 1998.

Branca Paolo (2003) Il vino nella cultura arabo-musulmana. Un genere letterario… e qualcosa di più. In: La civiltà del vino. Fonti, temi e produzioni vitivinicole dal Medioevo al Novecento. Atti del convegno (Monticelli Brusati, Antica Fratta, 5-6 ottobre 2001). Centro culturale artistico di Franciacorta e del Sebino, Brescia, pp. 165-191.

Anna Maria Grasso, Girolamo Fiorentino (2012) Archeologia e storia della vite e del vino nel medioevo italiano. Il contributo dell’archeobotanica e di nuove metodologie di analisi integrate per la caratterizzazione varietale applicate ai contesti archeologici della Puglia meridionale. 2012, VI Congresso Nazionale di Archeologia Medievale

AAVV (1988) Il vino nell’economia e nella Società italiana medioevale e moderna. Convegno di Studi Greve in Chianti, 21-24 maggio 1987 Firenze, in Quaderni della Rivista di Storia dell’Agricoltura, Accademia dei Georgofili Firenze.

Emilio Sereni (1961), Storia del paesaggio agrario italiano, Editori Laterza.

Pietro Stara (2013), Il discorso del vino – origine, identità, come problemi storico-sociali, ed. Zero in Condotta.

Giovanni Spani (2010-2011), Il vino di Boccaccio: Usi e abusi in alcune novelle del Decameron, Heliotropia 8-9.

Gino Tellini (2014), Il “figlio del sole” : vino e letteratura in Toscana. Soc. Ed. Fiorentina