“Vinum de vite dat nobis gaudia vite. /Si duo sunt vina, mihi de miliore propina. / Non prosunt vina, nisi fiat repetitio trina. / Dum quartum poto, succedunt gaudia voto. / Ad potum quintum mens vadit in laberintum. / Sexta potatio me cogi abite suppinum.” (Salimbene de Adam, XIII sec.)

“The wine of the vine gives us the joys of life. If there are two qualities of wine, give me the best. We do not enjoy wines if we do not repeat the drink three times. At the fourth, desire is followed by delights. On the fifth drink, the mind enters a labyrinth. The sixth drink makes me fall on my back. ” From the chronicles of Salimbene de Adam (13th century)

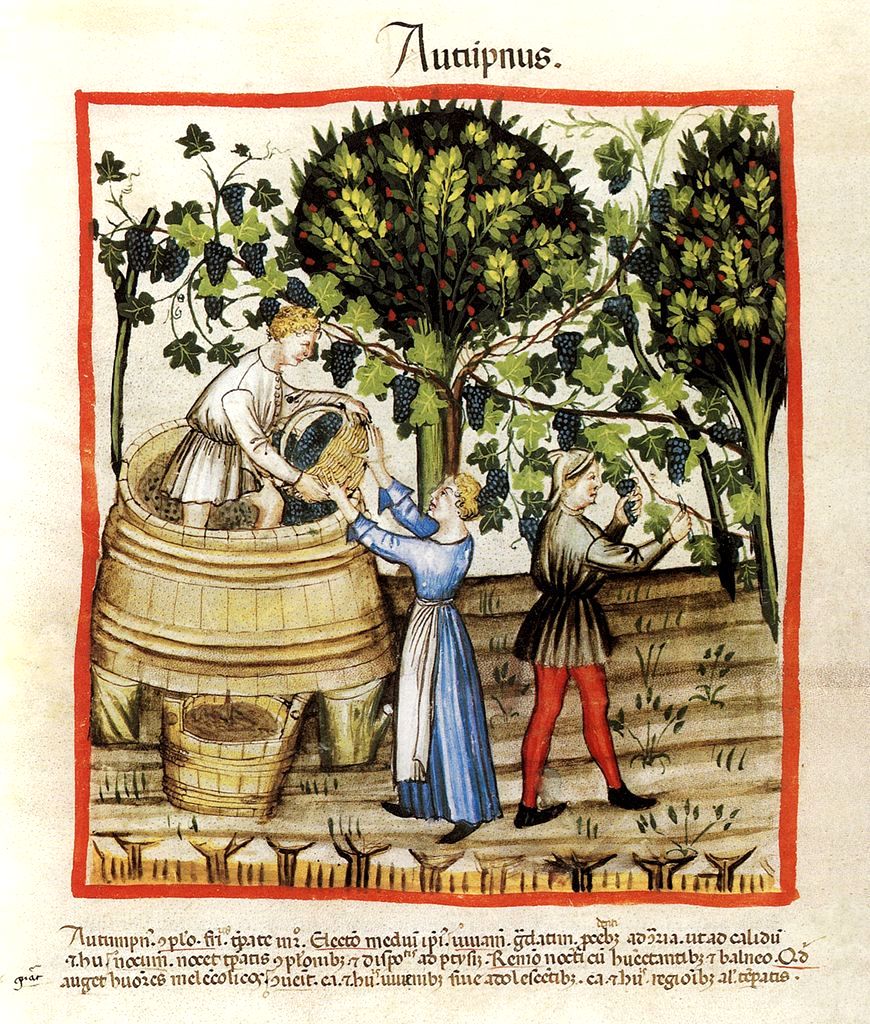

Between the end of the Early and the start of the Late Middle Ages, the greater political stability and the favorable climate led to notable progress in agriculture. The vineyards, in particular, expanded and spread more and more. The notable increase in production made wine go back to being the drink of the people in Italy, as it had already been in Roman times. It was different in other European countries. Where production was more difficult or wine was an imported drink, it remained for a long time only the prerogative of the rich.

The wine went from sign of prestige or a liturgical necessity to an economic activity. After the year 1000, the bourgeois agricultural property also spread, in particular from the 12th century. The wine production was the symbol of social ascent for the bourgeois. The increase in production will increasingly lead to its commercialization, marking the success over time of those territories that were located in places that facilitated its transport, such as the coastal areas and along the navigable rivers of Europe. Let’s go to discover how.

The viticulture spread very much In Italy. Each territory, even the least suitable, dedicated an important part of its agricultural land to the vine. The remarkable documentation we have of the period, especially between the 13th and 14th centuries, shows us an incredible spread of vines everywhere, both in the peripheral areas and in the centers of cities and villages. At the time, the local wines were anonymous, defined only by the color, the organoleptic characteristics, and the alcohol content. They were consumed essentially locally.

The increase in wine production became a concern of the legislator. In the municipal statutes there were many provisions related to the cultivation and management of the vineyards, at the date of the harvest, the transport, the retail and wholesale of grapes and wine, at the duties and the tariffs. In general, the regulations tended to push towards a production of quantities, capable of providing enough wine for the consumption of the community. Furthermore, the statutes were aimed at favoring the consumption of local wines and making it difficult for foreigners to enter (vina forensia).

In the thirteenth century, however, the poet Cecco Angiolieri wrote that he was tired of the local (Latin) wine and wanted to drink something different::

“… and all I want is Greek and Vernaccia wines, / because Latin wine bores me, …”.

In fact, the great availability of local wine pushed more and more the rich and powerful Italians to seek distinction in luxury products, represented at the time by the exotic wines of the eastern Mediterranean, which arrived together with spices, silk, jewels and the relics of the saints. Their prestige lay in the high price.

The wines traveled a lot from the thirteenth century onwards, throughout the Mediterranean, to and from Italy, passing through the three great trading posts of the time: Genoa, Pisa and Venice. The wine traveled in small barrels, by sea or river, on ships or barges. Upon departure (or arrival), the barrels were transferred to ox-drawn carts or to the burden of the mules. The above maritime republics dominated these trades for a long time, throughout the Mediterranean and towards the northern Europe.

The oriental wines were called in the documents of the time “ultramarine” (today we would say overseas) or “navigated“. They reached the final consumer at considerable cost, both for the long journey and for the numerous duties that were charged there. The Oriental wines, often generically also referred to as “wines of Romania“, came from the Byzantine Empire. In this generic group, several more specific origins will be distinguished later, such as the wine of Crete, Chios, Lesbos, Tire (now in Lebanon), … At the time, these were the few wines that endured very long journeys, thanks to the high alcohol content. They were white wines, sweet and fortified, concentrated by cooking the must or drying the grapes, enriched with spices, perfumes and honey. These exotic wines, whose purchase possibility was a status symbol of wealth and prestige, conquered the rich of the time for over three centuries, from the thirteenth to the fifteenth century. Their trade became a monopoly of the Venetians after the capture of Constantinople in 1204. During the 13th century, this trade increased more and more, thanks to the expansion of the possible buyers, no longer only nobles and ecclesiastics, but also the new rich bourgeois.

Genoa tried to counter the monopoly of Venice with the trade of local and southern wines, produced in the style of the wines of Romania. They were Ligurian Vernaccia and wines from southern Italy, coming from those areas that had remained for centuries under the Byzantine rule: Calabria and part of Campania. For the latters, the term “Greek” wine was born, which at the time was equivalent to “Byzantine”, as opposed to the so-called “Latin” wine, produced in the rest of Italy, but above all with very different characteristics. From Calabria, the Greek wines arrived in Naples. Here, they were taken over by Genoese and Pisan merchants, who market them throughout the western Mediterranean, in Northern Italy and the rest of Europe. The term “Greek” was then also used not only to indicate the real geographical origin, but for all the wines made with the same characteristics. This term has remained as legacy in the names of several current Italian wines and grape varieties.

Then, other Italian wines began to be among the most expensive. The wine Ribolla, also marketed by the Venetians, was perhaps originally from Friuli or Istria. It was a sweet and strong white wine, but less than the oriental ones. Trebbiano was a dry white wine, probably of Tuscan origin, widespread in many other regions. Furthermore, Vernaccia began to be produced also in Tuscany. As in the previous cases, in fact, the names of these wines were born from geographical links but then became indicative of a type of wine. At the time, they could therefore be produced in different territories, with the local varieties. Trebbiano and Vernaccia were mainly marketed by the Genoese and Pisans, then also by the Florentines.

Vernaccia, wine par excellence in The Decameron. Vernaccia was among the first wines to take a name in the Italian Middle Ages, thanks to the Genoese who managed to give it the status of luxury wine, capable of competing with the wines of Romania. The success then brought production out of the Ligurian borders, especially in Tuscany and Sardinia. This wine was praised by poets, such as Folgore from San Gimignano in the 13th century, and in the novellas (short stories) of Boccaccio or Sercambi of the 14th century. Above all, it is Boccaccio who frequently mentions it in the Decameron. In the short story “Calandrino and the heliotrope”, Vernaccia is the symbol of pure enjoyment. Maso tells of the Land of Bengodi (“Great Enjoying”) where the vineyards are tied with the sausages and the mountains are made of grated Parmesan cheese. There, it is possible to drink Vernaccia all day, which also flows in the rivers: “and nearby ran a river of Vernaccia, the best you ever drank, without any drop of water in it”. In the short story “Calandrino and the stolen pig”, Vernaccia takes on a magical value. Bruno and Buffalmacco, who enjoy making fun of the naive Calandrino, try to convince him to pretend the theft of his pig, to deceive his wife and enjoy the money. Because his refusal, they steal the pig secretly and accuse Calandrino of having implemented the plan on his own. At this point, they push him to organize a sort of “ordeal”, those tests of the most ancient Middle Ages in the balance between religion and magic, to demonstrate who was the author of the theft. They make him believe that they are able to prepare enchanted ginger biscuits, served with Vernaccia, which will be indigestible for the culprit of the theft. All the inhabitants of the village are invited to the test, who are served biscuits and wine. The two pranksters manage to give only Calandrino some biscuits made very bitter by the addition of aloe, blatantly demonstrating his guilt. The final joke is that the poor man is also forced to give them two capons, so that they do not tell anything about what happened to his wife. In another short story, Vernaccia also demonstrates healing abilities. In fact, the brigand-gentleman Ghino di Tacco cures the terrible stomach ache of the abbot of Clignì with a diet based on toast, broad beans and Vernaccia (“Ghino di Tacco and the abbot of Clignì”).

To be continued …

Bibliography:

Prof. Alfonso Marini (AA 2020-2021) Dispense del corso di storia medievale.

Pini, Antonio Ivan (2003) Il vino del ricco e il vino del povero. In: La civiltà del vino. Fonti, temi e produzioni vitivinicole dal Medioevo al Novecento. Atti del convegno (Monticelli Brusati, Antica Fratta, 5-6 ottobre 2001). Centro culturale artistico di Franciacorta e del Sebino, Brescia, pp. 585-598.

Antonio Saltini (1998), Per la storia delle pratiche di cantina (parte 1) enologia antica, enologia moderna: un solo vino, o bevande incomparabili? In Rivista di Storia dell’Agricoltura n.1, giugno 1998.

Anna Maria Grasso, Girolamo Fiorentino (2012) Archeologia e storia della vite e del vino nel medioevo italiano. Il contributo dell’archeobotanica e di nuove metodologie di analisi integrate per la caratterizzazione varietale applicate ai contesti archeologici della Puglia meridionale. 2012, VI Congresso Nazionale di Archeologia Medievale

AAVV (1988) Il vino nell’economia e nella Società italiana medioevale e moderna. Convegno di Studi Greve in Chianti, 21-24 maggio 1987 Firenze, in Quaderni della Rivista di Storia dell’Agricoltura, Accademia dei Georgofili Firenze.

Emilio Sereni (1961), Storia del paesaggio agrario italiano, Editori Laterza.

Pietro Stara (2013), Il discorso del vino – origine, identità, come problemi storico-sociali, ed. Zero in Condotta.