Our territory passed under the Roman domination during the III century BC. It was not as traumatic as elsewhere, in several respects (as I will tell you now).

The production of wine in our area in Roman times is well documented, thanks to the discovery of the remains of numerous villae (the estates of that time) that produced wine, olive oil and cereals. They were in the same area where most of today’s wineries are located: the foothills and the high plain between Bolgheri and Castagneto.

[info_box title=”A silver wine amphora” image=”” animate=””]

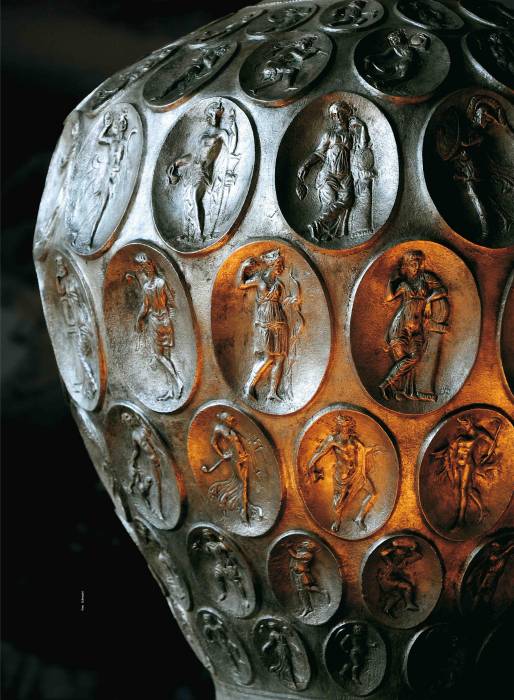

The Roman iconic object of our coast is a precious silver wine amphora, a single piece from the second half of the 4th century. A.D. It was found by a fisherman in the sea of the Gulf of Baratti in 1968. It could hold 22 liters of wine. It has very fine decorations, 132 ovals in each of which a different figure is depicted. There are divinities, characters linked to the cult of Cybele and to the Paris myth, Maenads and Bacchantes. The amphora had to have handles, unfortunately never found. It is kept at the Museum of the Territory of Piombino.

[/info_box]

Traveling along ancient roads

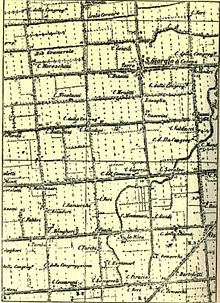

There were no significant towns in our territory (inside the black rectangle on the historical map, between Populonium and Vada Volaterrana), as in the Etruscan era.

Our area was essentially a strip of agricultural land, as today, between the hills to the east and the sea to the west. There were not the coastal pine forests at these times, today so characteristic: they will be planted by man many centuries later.

However, it was a well-populated stretch of coast, with the prevalence (as in the Etruscan era) of a scattered housing model, made up of little farms and villages. In Roman times numerous estates (villae) were also born and the surfaces of cultivated lands increased considerably. Several wooded areas were been deforested with the ancient practice of the fire. The reclamation works of the coastal wetlands, already started by the Etruscans, were also extended.

[one_third][info_box title=”The local administrative center” image=”” animate=””]

A fortress dominated our territory from the top of this hill for centuries. It was born in Etruscan times and remained in the Roman one.

This place was continually inhabited from Prehistory to the Middle Ages, when it took the name of Donoratico Castle (in the picture there are the remains of the medieval tower). It evidently was a strategic site, on the top of one of the first hills towards the sea, inclined so as to have a view of the whole coast in a northerly direction. The settlement became a fortress around the middle of the 4th century BC, one of those that Populonia used for the capillary control and defense of its territory. It occupied an area of about 7000 square meters, surrounded by an imposing city wall.

In Roman times it lost its original function and became the administrative center of the territory, in which more and more agricultural settlements were being born. Unfortunately, the site is closed, placed in a private property.

[/info_box][/one_third]

In Etruscan times, Populonium (Populonia) dominated in our area. In the new Roman era the center of power shifted to Volaterrae (Volterra) and our territory become part of the ager Volaterannus (the countryside of Volterra). It included throughout that agricultural area from us up to the promontory of Castiglioncello, and in the Cecina Valley. It was not a very rich agricultural territory but, as we will see, it was exceptionally stable throughout the Roman period, from both social and economic points of view.

One of the most important changes in the Roman era was certainly the construction of the Via Aurelia (Aurelian Way, in blue on the map), one of the great Roman consular roads, built based on the previous Etruscan road system. Nothing remains of this ancient road today. The last testimonies of some original stretches dates to the eighteenth century. The current state road SS1 Aurelia (not the freeway) has almost the same route of the ancient Way; it is thought it was only a little more inland with respect to the actual. The Aurelian Way was built in the 3rd century BC to connect Rome with Cerveteri (Caere on the map). With the conquest of the rest of Etruria, it was continued till Pisa (Pisae), but here he remained firm for some time, due to the difficulty in overcoming the swamps of Versilia area (called Fossae Papirianae) and for the tenacious opposition of the populations of the Apuan Alps. It was completed towards the Liguria region only in the Augustan age (I century AC).

The most important inhabited center in the south was still Populonia (in this era Populonio or Populonium), the ancient Etrusca city Pupluna (or Fufluna). Another small port was born from one of his suburb during Roman period, called Falesia, from which Piombino will develop in the Middle Ages. However, during the Roman times, the powerful Etruscan city began to decline even if, for the first centuries, both the principal port (in the Gulf of Baratti) and the mining district remained important. In fact, iron was useful to supply armies with weapons.

From the 3rd century AD, the mining also stopped and Populonia practically became a village. In the 4th century, nothing remained but ruins of the ancient and glorious city, as recounted by Claudius Rutilius Namatianus, which had traveled by ship along the coast in 415 AD , returning from Rome to the native Gallia:

Close by, Populonia opens its dark coast bringing the natural bay right into its fields. …

No longer visible are the monuments of the past: time that devours all has consumed its thick bulwarks.

Bare traces are visible amidst crumbled walls; buried roofs lie beneath the general ruins.

Nor should we fret that mortal bodies dissolve: look well, learn from examples such as this that cities can die.

Claudius Rutilius Namazianus, 417 AC (The Return, I, 401-414)

The coaching inn in the Aurelian Way was in Aquae Populoniae, today Venturina, where there are still the thermal baths. The first place after in the map is Vada Volaterrana (more or less the current Vada, today a little village near Cecina), the ancient port of Volterra, coaching inn and also a center of a saltworks area.

Behind Vada, in the hinterland of the Cecina Valley, there was Volaterrae (Volterra), the ancient Etruscan city Velathri. Unlike Populonia, this city was able to conquer an import role also in this new times. Between the age of Caesar and that of Augustus, it became Colonia Augusta, the political and military center of our entire coast, going through a period of great prosperity. However, in Imperial times, its decline started, because the city was isolated by now from the main street system.

A soft Romanization.

As mentioned, the Romanization was been here less traumatic than elsewhere, especially in the countryside, thanks to the good work of political mediation made by the local aristocratic families. After a bit of ups and downs in their relationship with Rome, they managed to maintain their power, as well as the majority of their land properties.

In other areas of Etruria (and more) the Roman colonization took place according to a more brutal model of conquest: the lands were taken away from the old owners, were centuriated *, divided in small lots and assigned to the Roman veterans. The old Etruscan families disappeared from the positions of power. Later, with the expansion of the properties of the new ruling class, the villae were born, real specialized agricultural estates, to the detriment of small farmers above all. These estates were based essentially on slave labor and they were quite detached from the territorial context.

In our territory this model of colonization occurred only marginally. The landowners remained mostly the same old aristocratic families with Etruscan origin, well-established for centuries, controlling the agriculture and mining resources. They no longer lived in the countryside, but mostly in Volterra, the center of power, or even in Rome, like the richest local family, the Caecinae (Romanization of the Etruscan surname Ceicna).

[one_second][info_box title=”The villa in Bolgheri of a noble from Volterra” image=”” animate=””]

Not so far from Guado al Melo along the Bolgherese Way, in the locality called “Il Puntone di Bolgheri”, there was a Roman villa, today disappeared. Now there is a vineyard of our friend Valerio Cavallini (Campo al Coccio Winery).

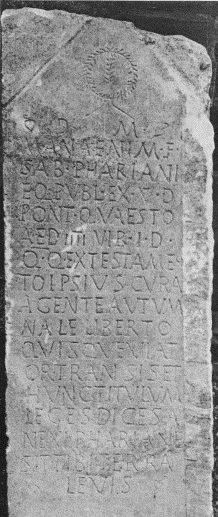

Nothing remains except for a funerary stele from the II-III centuries AC, kept in the Cecina Museum, that allowed us to know the ancient owner of the villa.

The stele inscription tells us that it was commissioned by the freedman Autumnalis for a testamentary disposition, to remember the late noble owner. He was a lord from Volterra, the knight Marcus Anaenius Pharianus, municipal magistrate and many other things (the list of titles is very long). The Romanized name does not hide his Etruscan ancestry.

The inscription ends with the classic Latin phrase of the cult of the dead:

SIT TIBI TERRA LEVIS

may the ground be light to you

[/info_box][/one_second]

*Centuriation: the conquered territory was subdivided into centuriae (squares with side of 710 m, with a surface of about 50 hectares) which were the capillary base of the Roman agrarian, social, economic, legal and administrative system. This sort of chessboard was defined by two fundamental lines: the decumanus (generally traced in east-west direction) and the cardus (usually north-south). The centuriae could then be divided into even smaller units, with secondary parallel lines. Once the operations of centuriation and land assignment were carried out, the territory was represented on maps, called formae (very similar to the actual cadastral maps), preserved in duplicate in Rome and in the provincial capital.

They weren’t just ideal lines: along them the boundary fences or hedges were born, as well as the secondary and local public roads leading to the farms, up to the wider system of aqueducts and main roads. The ancient Roman partition of the territory has remained almost unchanged in different parts of Italy, until our days.

During the transition between Etruscan civilization and Romanization, the noble estates of our territory also evolved towards the model of the Roman agricultural villa. However, they were not the property of conquerors but of the descendants of the historical local noble families, who continued to co-exist in a balanced way with the communities of the area.

The basic social model is very different from the slave villae. The workers were, above all, free inhabitants of the nearby settlements. The owners were linked to them by relations of an ancient Etruscan clientele.

This social situation was also reflected in the relationship with small farmers, who did not tend to disappear here but rather to grow in their number. Between the third and second centuries BC, archaeologists have experienced a boom of new small farms (26 in our area). It is not known if the farmers were proprietors or not, more likely they were lessees of lands made available by the nobles.

Even agricultural techniques did not change that much. Etruscan and Roman had in common the same original agricultural matrix, already described here. It was made of rows of vines (supported by trees) or olive trees, alternating with strips of land dedicated to arable land. The Romans, in addition to tracing lines and boundaries, did not greatly change the hydraulic arrangement and the processing of the soils, except to introduce the implantation of vines in small dimples. However, we will learn more later about Roman viticulture and its important developments.

(… continues in the next post, in which we will know better the villae of our territory)