We all already know that the Etruscans were great navigators and traders but perhaps it is less known that they also traded their wine, a sort of primordial export from Tuscany.

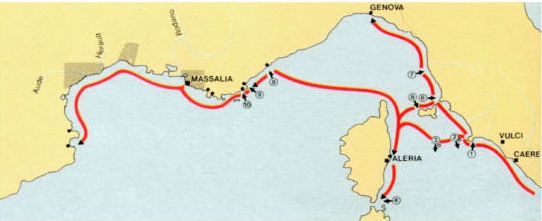

The history of Etruscan trade began around the IX century BC, but it intensified especially from the 8th century onwards. It was interrupted only by the Roman conquest (II-I century BC). Located in a pivotal region for trade between the East and the West, the Etruscans were able to make the most of this favorable position. The Etruscan merchants became known throughout the Mediterranean and the Tyrrhenian Sea, controlled by the fleet, became almost an exclusive space. Brown arrows: trade routes and the widespread use of Etruscan products.

The wine trade was very intense between the seventh century and the first half of the fifth century B.C. Before these period, the wine-growing techniques were noticeably improved. The strong increase in production created a surplus, with respect to domestic consumption, pushing the Etruscan to wine commercialization.

The wine trade was very intense between the seventh century and the first half of the fifth century B.C. Before these period, the wine-growing techniques were strongly improved. The increase in production created a surplus, with respect to domestic consumption, pushing the Etruscan to wine commercialization.

It was a vast trade, documented by the discovery of Etruscan wine amphorae in many regions: in Lazio, in Campania, in the Greek colonies of eastern Sicily, in Calabria, in Sardinia, in Corsica, in southern France and in the Iberian peninsula, both on the coasts Mediterranean and the southern Atlantic areas. There was also a minor trade by land, both internally and towards the territories of central Europe, where numerous objects of the Etruscan symposium have found.

The most important market were the Celto-Ligurian settlements of Southern France, such as Saint-Blaise in Provence, Lattes and La Monedière in Languedoc, penetrating for some tens of kilometers inland along the waterways. Large quantities of bucchero vases and Etruscan wine amphorae were found in the archaeological remains of more than 70 sites in the region.

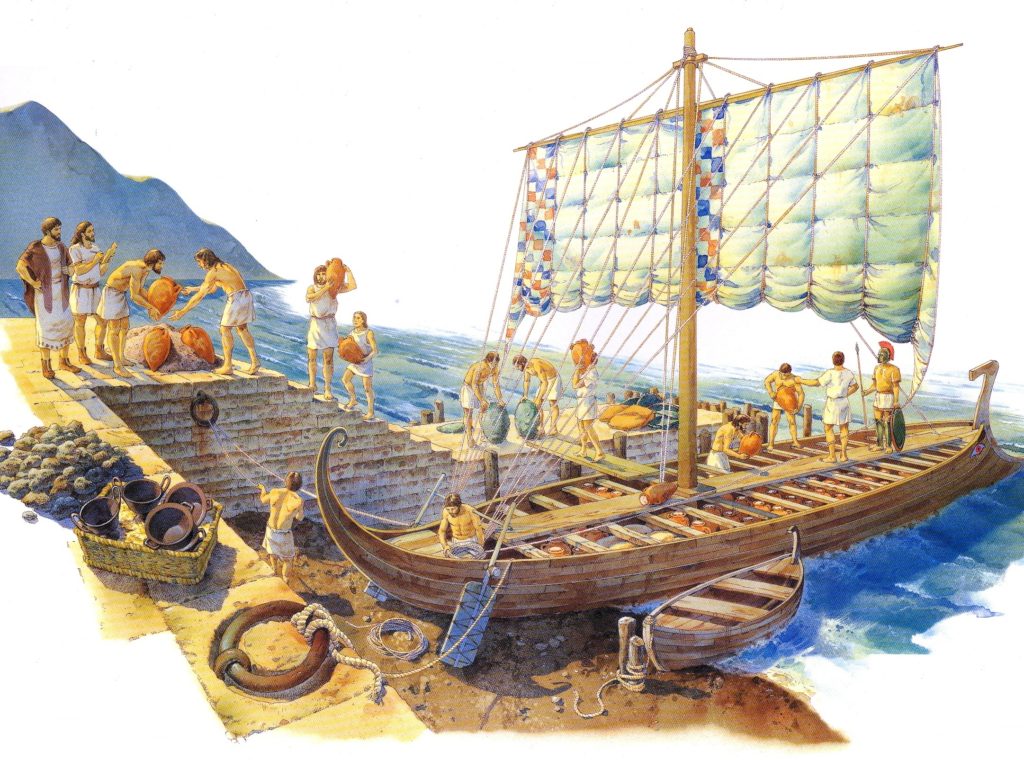

We can also follow the routes of these trips thanks to the remains of shipwrecks found in Cap d’Antibes, Bon Porté, Point du Dattier and other places. From Etruria, the merchants followed the islands of the Tuscan archipelago and passed near Corsica. On the seabed, Etruscan ships have been found with entire loads of wine amphorae and fine tableware.

At that time in the south of France wine was not yet known and, in return, the Etruscans procured various commodities, probably skins, cattle, slaves, especially tin that, along the Rhone route, came from Cornwall (I remember that tin was fundamental for the production of bronze, in alloy with copper).

This trade in wine came less from the 6th century BC because of the colonization of the Focei (from Focea, the Greek city of Ionia, in present-day Turkey). These gradually supplanted the Etruscans, imposing a real territorial domain, especially towards the end of the century.

From that moment on, the markets of Southern France began to supply from the wine production of Marseilles (Massalia), which had been founded by the Focei around 600 BC. The Etruscan wine trade diminished significantly and focused mainly on crafts and luxury goods.

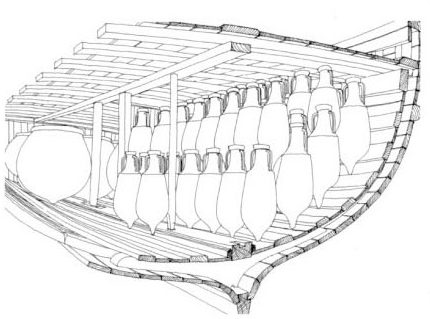

The wine was transported in terracotta amphorae,

also used for preservation, ancestors of the most famous Roman amphorae. The Etruscan amphora appears to have originated from Phoenician models and appeared with the beginning of the commercialization of the product. At the beginning they had red paint inscriptions, as if to evoke the practice of giving. However then they become standardized, they become all identical, without decoration, a real mass production. Inside they were coated with resin and closed with cork stoppers sealed with pitch. The shape was different depending on the place of production and evolved over time towards increasingly elongated shapes, to facilitate storage in ships.

In the holds, the amphorae were stacked in parallel rows, one above the other, taking advantage of the spaces between the handles of the row below to insert the tip of the one above. The loads were balanced so as to avoid the imbalance of the boat. The interstices between the amphorae were filled with juniper or heather twigs, rushes or fagots, to avoid breakage and movement during transport.

The Etruscans kidnap Dionysus

From the 6th century B.C. the Etruscan merchant appeared depicted in Greek literature as a pirate, while the Phoenician one had the role of the cunning merchant. The Greek one, of course, progressively triumphs over obstacles, imposing himself on others. This iconography, obviously very biased, had a historical background however: the commercial trips of the time were not entirely unrelated to episodes of raids. However, it is thought that, rather than pirate acts, it was a sort of corsair war.

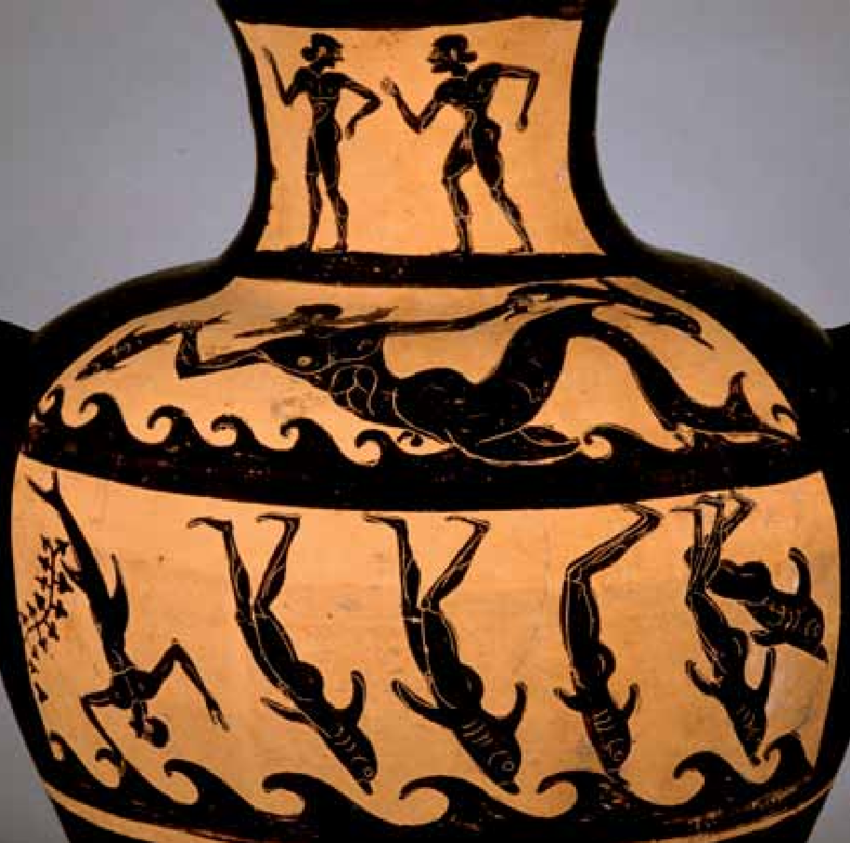

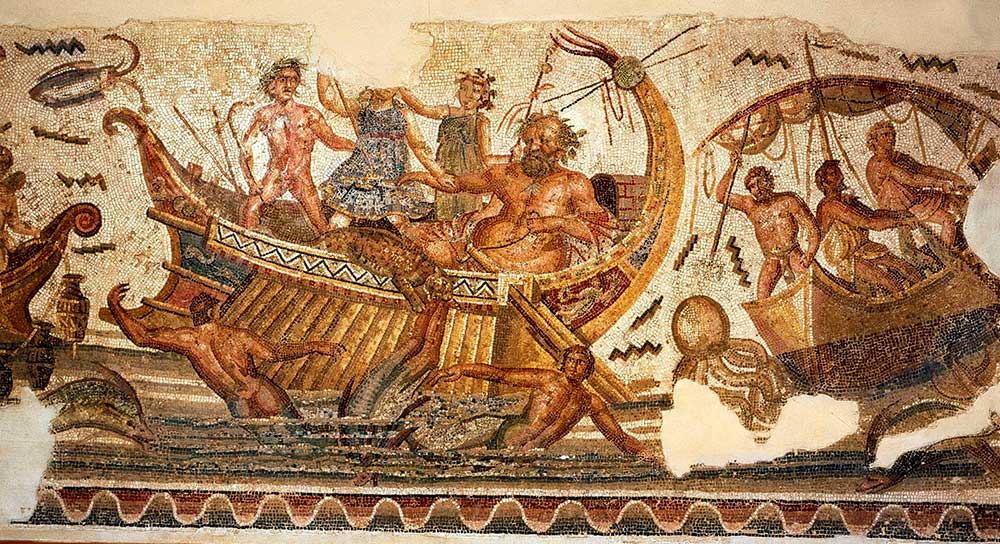

The figure of the Etruscan-merchant, but above all of the Etruscan-corsair, caused the spread of a myth that tells of the kidnapping of Dionysus by the Etruscan, represented on Greek vessels starting from the VI century BC. This myth appears for the first time in the Hymn 7 attributed to Homer, probably reporting archaic oral narratives.

The myth tells that the Etruscans found a beautiful sleeping boy on an island, with black curls and a rich purple coat.

… Presently there came swiftly over the sparkling sea Tyrsenian pirates on a well-decked ship —a miserable doom led them on. …

Thinking he was the son of a king, they took him to ask for his ransom. Dionysus, awakened tied up on the ship, turned into a bear and then into a lion, while vine shoots wrapped around the main mast. The pirates, terrified, threw themselves into the sea and were transformed into dolphins. The God spared only the helmsman, who had opposed from the beginning the attempt to tie him, since he had guessed the divine nature of the young men.

It seems that the Etruscans appreciated this myth, in fact they themselves represented it, as in the hydria (water amphora) of Toledo.

Apart from Homer, this myth is rarely remembered in Greek literature, except in later periods, where it appears with different additions or variations. In the Hellenistic period Pindar claims that the abduction was “commissioned” by Hera, with Silenus and the Satyrs leaving for his research. It is even more frequent in the Greek literature of the Roman period, with Apollodorus, Nonnus of Panopolis and other authors.

In Rome the myth is mentioned by Ovid in the Metamorphoses, according to which the kidnapping would have taken place on the island of Chios. When the young man wakes up, he asks to be taken to Naxos. The pirates pretent only to go along his request and, when Dionysus realizes it, the prodigies begin. The ivy and the vine wrap around the mast of the ship, different fairs appear. The pirates who throw themselves into the sea are described at different stages of the metamorphosis into dolphins. Then they emerge and weave a dance around the ship. The saved helmsman comes to Delos and becomes a follower of the worship of God.

In the Oedipus by Seneca the prodigies are still different: the sea becomes a meadow, with also trees and birds. Hyginus tells that the companions of Dionysus (who was not alone, in this case) begin to sing a wonderful song that fascinates the pirates, who begin to dance and fall into the sea cause of the enthusiasm. Lucian recalls this story, saying that Dionysus uses the dance to subdue the Tyrrhenians, emphasizing its importance in the worship of God.

Scholars consider that originally the myth was linked to the initiation rites to the Dionysiac mysteries , as a teaching or as a demonstration of punishment for those who do not want to recognize the God. Then it became a sort of Greek propaganda against Etruscan acts of piracy. In Hellenistic and Roman times, however, it also took on an eschatological connotation, related to the cult of Dionysus, God of transformation and renewal, which leads to salvation.

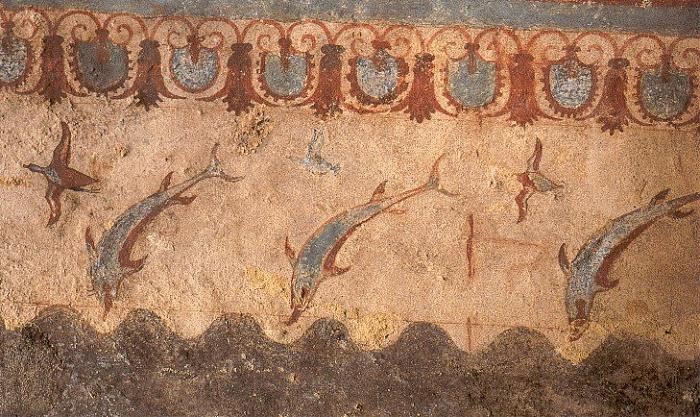

The relationship between Dionysus (wine) and the sea are elements and metaphors of the passage between life and death, however very present in Greek culture and then also in the Etruscan one. The journey by sea metaphorically represented the journey to the afterlife. The Etruscans believed that it precisely the dolphins accompanied the dead to the Isle of the Blessed. The figure of the dolphin is in fact proposed in Etruscan art with symbolic-ritual significance linked to death, as in several tombs, but also a good omen. these aquatic animals were surely very familiar to this people of navigators.

This bond will remain even in Roman art , with the representation of this myth in funerary monuments. However, it was also rapresented in mosaics of private houes.

I like to think of this myth in a different way too. The Etruscans kidnap the God of wine, Dionysus, or rather the very soul of wine, and take it to the West, in Italy, which will increasingly become the land of wine par excellence.

Hymn 7 – To Dionysus (by Homer)

I will tell of Dionysus, the son of glorious Semele, how he appeared on a jutting headland by the shore of the fruitless sea, seeming like a stripling in the first flush of manhood: his rich, dark hair was waving about him, and on his strong shoulders he wore a purple robe. Presently there came swiftly over the sparkling sea Tyrsenian pirates on a well-decked ship —a miserable doom led them on. When they saw him they made signs to one another and sprang out quickly, and seizing him straightway put him on board their ship exultingly; for they thought him the son of heaven-nurtured kings. They sought to bind him with rude bonds, but the bonds would not hold him, and the withes fell far away from his hands and feet: and he sat with a smile in his dark eyes. Then the helmsman understood all and cried out at once to his fellows and said:

“Madmen! what god is this whom you have taken and bind, strong that he is? Not even the well-built ship can carry him. Surely this is either Zeus or Apollo who has the silver bow, or Poseidon, for he looks not like mortal men but like the gods who dwell on Olympus. Come, then, let us set him free upon the dark shore at once: do not lay hands on him, lest he grow angry and stir up dangerous winds and heavy squalls.”

So said he: but the master chid him with taunting words: “Madman, mark the wind and help hoist sail on the ship: catch all the sheets. As for this fellow we men will see to him: I reckon he is bound for Egypt or for Cyprus or to the Hyperboreans or further still. But in the end he will speak out and tell us his friends and all his wealth and his brothers, now that providence has thrown him in our way.”

When he had said this, he had mast and sail hoisted on the ship, and the wind filled the sail and the crew hauled taut the sheets on either side. But soon strange things were seen among them. First of all sweet, fragrant wine ran streaming throughout all the black ship and a heavenly smell arose, so that all the seamen were seized with amazement when they saw it. And all at once a vine spread out both ways along the top of the sail with many clusters hanging down from it, and a dark ivy-plant twined about the mast, blossoming with flowers, and with rich berries growing on it; and all the thole-pins were covered with garlands. When the pirates saw all this, then at last they bade the helmsman to put the ship to land. But the god changed into a dreadful lion there on the ship, in the bows, and roared loudly: amidships also he showed his wonders and created a shaggy bear which stood up ravening, while on the forepeak was the lion glaring fiercely with scowling brows. And so the sailors fled into the stern and crowded bemused about the right-minded helmsman, until suddenly the lion sprang upon the master and seized him; and when the sailors saw it they leapt out overboard one and all into the bright sea, escaping from a miserable fate, and were changed into dolphins. But on the helmsman Dionysus had mercy and held him back and made him altogether happy, saying to him: “Take courage, good…; you have found favour with my heart. I am loud-crying Dionysus whom Cadmus’ daughter Semele bare of union with Zeus.” Hail, child of fair-faced Semele! He who forgets you can in no wise order sweet song.

Il mito di Dioniso e i Pirati Tirreni in epoca romana, Lucia Romizzi Latomus T. 62, Fasc. 2 (AVRIL-JUIN 2003), pp. 352-361 (12 pages) Published by: Société d’Études Latines de Bruxelles

Cristofani, Etruschi, ed. Giunti.

Gli etruschi, abili commercianti e navigatori. Gli scambi, i prodotti che compravano e vendevano, gli empori di Finestre sull’Arte, scritto il 24/06/2018