You may have read somewhere about regenerative viticulture (or regenerative agriculture more generally).

What is it all about?

The name may sound like something new, a new way of managing the vineyard. In reality, as you will see, it encompasses a range of practices that are already used by who, as us, conduct our vineyards in a sustainable way. In particular, the concept of “regeneration” refers to the soil. Thus, the regenerative viticulture refers to the sustainable vineyard management that is primarily aimed at maintaining a viable and healthy soil.

I have also read about even more special and niche terms, such as syntropic agriculture, which focuses primarily on preserving and increasing the biodiversity of agricultural soil.

As you may have noticed, every so often a new expression or definition related to viticultural (or winery) techniques comes up in our industry. However, they often do not invent anything new. Actually, they bring attention to some particular aspect. We cannot deny that they can also be useful “ploys” to revitalize the communication, which, in the world of wine or agriculture in general, is often languishing. On the other hand, this is a slow and unvaried sector by nature, not like others that churn out news all the time. All this makes it ill-suited to today’s super-fast world of communication. The risk, however, is to create more confusion than information, as unfortunately sometimes happens.

The properties of a healthy soil

What does a “healthy soil” mean first of all? It sounds like a strange expression but it is now frequently used. It can be better understood if we break down the different properties of soil, which are three: physical, chemical and biological.

The physical properties of a soil are related to its structure. A healthy soil has a porous and stable surface part, which is the exact opposite of a soil that is compacted or undergoing erosion. So, there are excellent gas exchanges, roots can grow in it optimally (in the first layers most of the nutrients are found), there is no erosion, … In addition, it must be deep enough to allow the roots to stretch even deep in search of water, depending on the type of water availability of the land. It must have good drainage, to avoid root asphyxiation in case of rainfall, especially if prolonged or intense.

The chemical properties of soil are optimal, first of all, if there are no pollutants. Considering that we are starting from “clean” soil, we must be first of all not to pollute it. So, the first point is to respect the rules of integrated viticulture, which avoids soil pollution with products used for vineyard defense or otherwise. A healthy soil then has an optimal nutrient content for the vines (the mineral salts). There must be no deficiencies but no excesses either. Finally, the levels of certain natural compounds, such as sodium chloride, which can be an obstacle to root development, must be contained.

Finally, there are the biological properties of a healthy soil. Of course, they refer to a high level of biodiversity in the soil, that is, the organisms that populate it, called the biome as a whole. In a healthy soil there is a high presence of “beneficial” organisms and a low pressure of pests. The useful organisms include the broad category of those that intervene to keep the vine pest population under control, acting as predators, competitors or (in turn) pests. This is the biological control. We apply what is called conservation bio-control, that is, the presence of wild fauna is encouraged. The artificial release of organisms is avoided because it is an unsustainable practice for two reasons. The first is that organisms released in the wild often struggle to survive, so it may just be a waste of time (and money). In a positive case, the introduction of non-local species would still be ill-advised because it could be a detriment to the ecosystem. The introduction of insects or other organisms can lead to downsides that are not always easy to predict.

Another fundamental class of useful soil organisms are those that participate in the process of organic matter degradation, starting with the shredding of organic debris, its translocation into the soil and the actual degradation. Many categories fall into this category, from earthworms to millipedes, snails, insects and other arthropods, protozoa, nematodes, fungi, bacteria … The latter are those that carry out the actual degradation and today are often referred to by the collective term soil microbiome. The natural phenomenon of degradation has given scholars in the field the idea to create state-of-the-art defense products that not only act at low doses but are also biodegradable. The higher the activity of the biome, the faster and more efficient the process of their degradation.

Another well-known class of soil organisms are the mycorrhizae, which are those fungi that can enter into symbiosis with the roots of vines (and other plants), in a mutually favorable exchange. Without going into detail, the mycorrhizae take carbohydrates from the plant. In return, they “help” the roots in absorbing water and some mineral elements. In fact, they form a network of very thin hyphae that manages to colonize the soil with a very dense density, reaching even where the vine roots, which have a larger diameter, cannot. The mycorrhizae occur naturally in healthy soil. Again, scholars have seen that artificial addition is often unnecessary: if the situation is favorable, these fungi develop spontaneously. If the conditions are not suitable, even if we artificially release them, they will not be able to develop and survive.

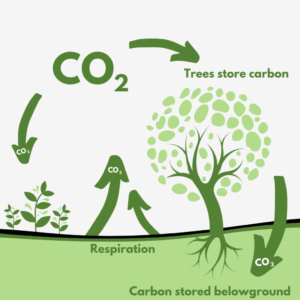

Finally, I would like to remind you that the high level of biodiversity leads to greatly increased carbon dioxide sequestration in the soil.

How regenerative viticulture works.

Several agricultural practices promote the aspects just described related to a healthy soil.

The first fundamental step is, of course, to implement a sustainable vineyard defense, that is, based on low-impact integrated viticulture. This is essential to avoid polluting so as to preserve the chemical and biological characteristics of the soil.

The second fundamental concept of regenerative viticulture is minimal tillage. This is a cornerstone of all areas of integrated viticulture, that is, to decrease intervention as much as possible, consistent with maintaining good vineyard management.

Allow me an aside. This concept is often poorly understood or underestimated. Conversely, it is often misrepresented or emphasized, going from what is intelligent work to the idea of abandonment, that nature does everything by itself. Minimum tillage is a contained action but knowing what you are doing and why. In fact, it must be contextualized case by case: for the type of soil, the climate, the meteorological trend of the specific period, the moment of the vine cycle, … The concept is therefore to work as little as possible, unless the situation requires it for the good of the vineyard.

The general concept of minimum tillage of integrated viticulture, which involves reducing all entries into the vineyard for each type of work, ensures that the soil is not compacted by the continuous passage of agricultural vehicles. The scholars have in fact demonstrated how compacted soil worsens in terms of softness, water and gas exchange. Furthermore, its biodiversity significantly decreases.

In the specifics of ground works, we talk about minimal tillage both as frequency and depth. The benefits are many and invest several aspects. The soil should be worked as little as possible to avoid ruining the superficial vine’s roots, which are numerous and essential for the absorption of nutrients and, in some cases, water. It is always best to avoid too deep tilling, which goes to remixing not vital layers with the more superficial vital layers. Minimal tillage generally has the consequence of greater preservation of biodiversity.

The soil cover with natural grass is closely related to minimal tillage and it is another cornerstone of regenerative viticulture. The advantages of crop covering instead of bare soil are widely recognized. In short, the cover helps to improve all soil properties. In fact, there is increased porosity and softness. The cover crop avoids or contains erosion problems. It maintains a lower soil temperature, with less evaporation. If there is too much drought, the grass dries up spontaneously, not creating competition with the vines. Conversely, the grass helps absorb any excess water and also makes the soil more feasible after rainfall.

The presence of a crop cover promotes biodiversity, including of the soil biome. It allows faster and more effective degradation of organic matter, improving the presence of plant nutrients. The biome is also responsible for the degradation of some compounds used in sustainable defense, as mentioned above. The grass itself acts as a physical and biological barrier, for example, in case of overfertilization done by mistake. Many substances are retained by the grass and do not pass into the water table.

Why is seeded lawn not chosen? This management is reduced to a few months per year. It also involves more inputs into the vineyard, as well as depressing biodiversity. In contrast, the natural lawn costs nothing, follows the rhythm of the seasons, has blooms of many species at different times of the year, thus providing an attractive environment for microfauna. It used to be recommended to sow legumes, to enrich the soil with nitrogen by green manure. It has long been the case that industry studies have shown that the nitrogen (and other) supply is not so different between green manure from wild grass and seeded legumes. The difference is offset by the many other listed benefits .

Finally, the type of soil fertilization is crucial. Mainly, except in cases of exceptional and point deficiencies that require other interventions, the ideal fertilization for regenerative viticulture is done with organic matter of plant origin. This is all the plant remains of the vineyard, from the green manure of the meadow, the pruning shoots shredded on site, the leaves, the remains of the stalks, … More than making compost piles, it is important to leave or distribute this organic matter evenly over the entire surface of the vineyard. This organic layer, until its degradation, helps to keep the soil temperature low and limit evaporation. Moreover, in this way we not only achieve the result of fertilizing but also nourishing and developing the soil biome in a widespread way. If we only make heaps, the microfauna will develop only in those places. Manure fertilization, on the other hand, does not seem to be so sustainable. Over time it can worsen the chemical characteristics of the soil, leading to excessive salinization and nitrate accumulation. It is also unsustainable if it comes from intensive livestock farming. Add to that the travel, if one cannot get supplies in close proximity.

So, in conclusion, soil care is a key element for sustainability and optimal vineyard management. Regenerative agriculture, or viticulture, is about just that.

I invite you to also reread two articles on roots (here and here) that delve into these and other aspects related to the relationship of the vine to the soil.