The Etruscans were the first winegrowers in Italy, beginning from the wild varieties.

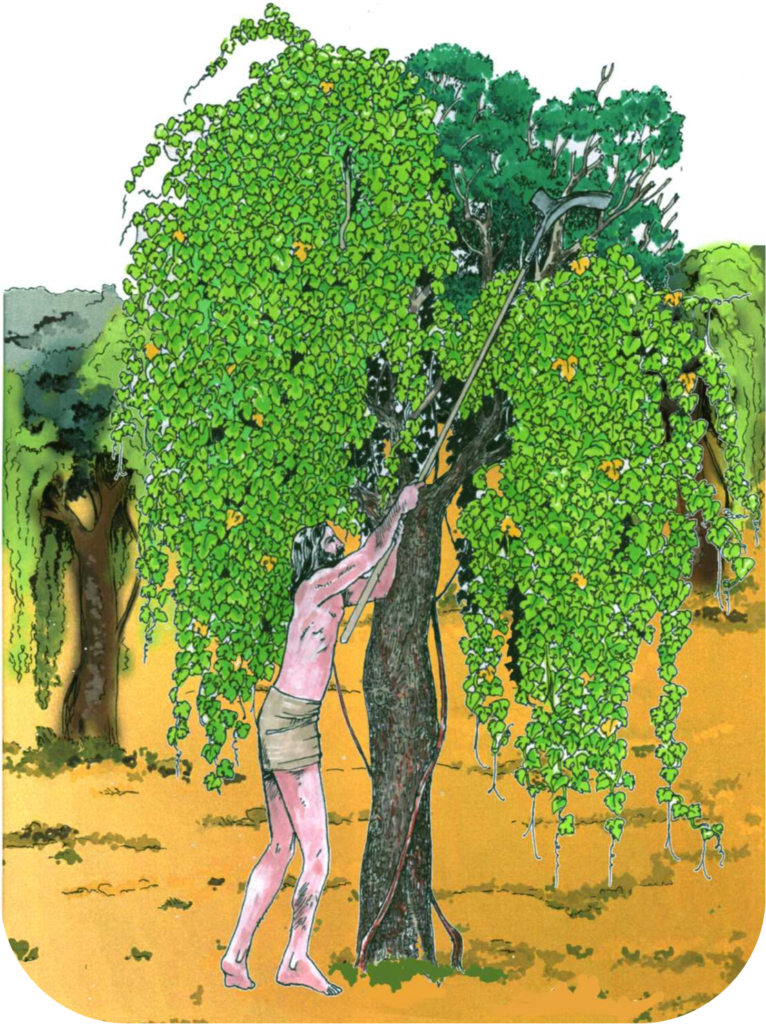

The wild grapevine is a local plant in the Mediterranean area. In the more ancient times, people began to gather its fruits in the woods.

The wild vine (Vitis vinifera sylvestris) is a native species of the Mediterranean area and, above all, in Italy, it finds its ideal conditions. Even today, it is possible to find wild vines in our woods (even if you have to make attention to distinguish them from vines became wild, from old abandoned vineyards). The varieties we cultivate today derive from the wild vine, modified through millennia by selections and crossings carried out by man.

Returning to the Etruscans, scholars hypothesize that they cultivated the vine since the Bronze Age, however at least from the twelfth century B.C.

Later, with the development of civilization, being great navigators and merchants, they had increasingly intense contacts with the peoples of the eastern Mediterranean (especially with the Greeks), where culture and viticulture techniques were already more evolved. This allowed them to refine production techniques, to import new tools and new practices of working. New oriental vine varieties were also imported (whose process of domestication began in a much more remote era in the Caucasus area). These new vines were cultivated and crossed with local varieties too.

Thanks to these influences, the primitive Etruscan viticulture grew and grew over the centuries, and wine production increased in quantity and quality. So, from the 6th century B.C., began also the overseas trade (which we will discuss later).

The Etruscans cultivated vines in the same manner they saw these plants grow wild in the woods. The vine is a climbing shrub, a species of liana. In a wood, its natural environment in our latitudes, it tends to climb up a tree to reach the light as possible (it is very heliophilous specie). However, it is not a parasite: the vine does not weaken the tree on which it clings.

Today the Etruscan cultivation system name is “married vine”, “vite maritata” in Italian. The vine is like “married” to the tree. This definition is not Etruscan but was born later, as we will see. The Etruscan word was “àitason”.

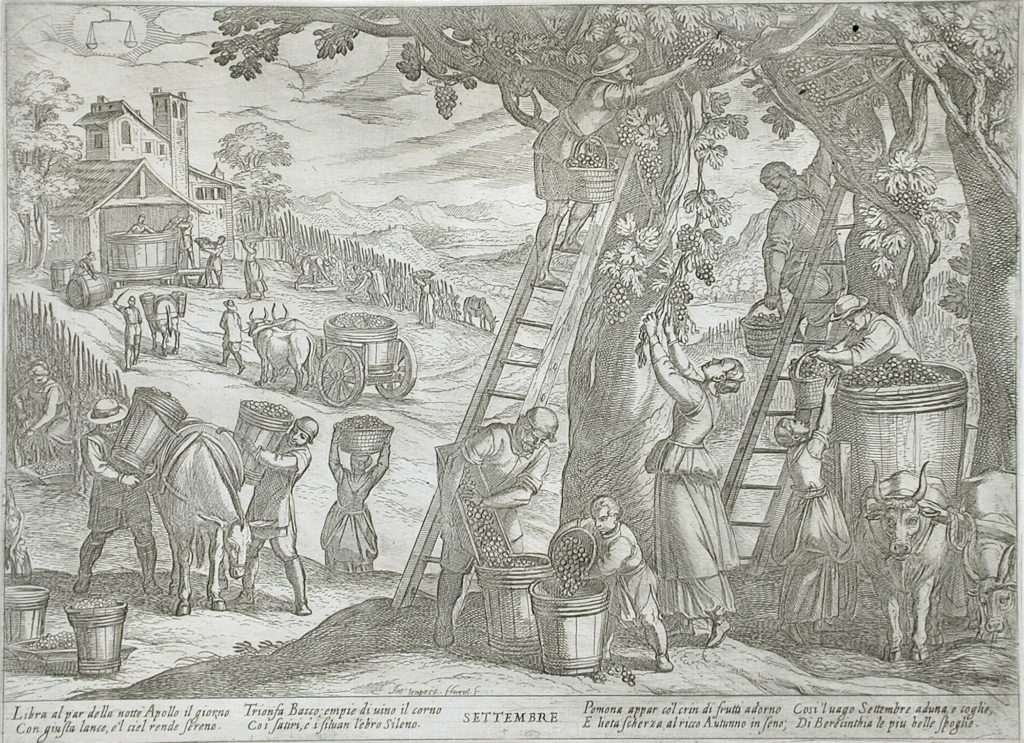

The vines were married to poplars, maples, elms, olive trees and various fruit trees. Originally they were not pruned, later they were subject to long pruning. The vine therefore tended to grow a lot, to have very long shoots. They picked up the grapes with the hands or with sickles, with ladders or using instruments with a very long handle.

The growing of vines in Etruria was not specialized: there was not a vineyard, as we understand it today. Instead, the vines were promiscuous with other crops (alternating with cereal fields, olive trees, fruit trees, etc.).

The “married vine” has remained in the Italian wine culture until almost our days, in all those territories where in ancient times the Etruscan civilization had arrived.

The Etruscans, from the original area of Tuscany and upper Lazio (called “Historic Etruria”) then widened their borders, expanding to Campania, to the south, and Emilia Romagna to the north. In Campania there is still today the border between the Etruscan wine culture (more to the north) and the Greek one (the vine-training system called “alberello“). In the latter, the vine was cultivated as a low stump, without support or with “dead” support (a pole). The Sele River marked, more or less, this border.

The Etruscans brought their advanced wine culture in the conquered lands, spreading it also to neighboring peoples, such the Cisalpine Gauls (the Cisalpine Gaul corresponds to a good part of the current northern Italy).

The Etruscans transmitted a great part of their culture to the nascent Roman civilization, including viticulture and wine production. According to the tradition, king Numa (one of the seven early kings of Rome), Etruscan by birth, taught the viticulture to the Romans.

In fact, in ancient Roman time, as witnessed in the De Agri Culture by Cato (II century BC), the cultivation of the vine was made in the Etruscan manner, marrying it to the elm or fig tree. The Etruscan àitason became the Latin arbustum (vitatum), which Cato sometimes also calls vinea, as well as Cicero does.

Varro, however, in De Re Rustica (39 B.C.) begun to distinguish two different forms of vine cultivation. Probably, in his time, a new form of viticulture emerges in Roman territories, the Greek one, already mentioned above. The word arbustum remains to indicate the married vine. Vinea becomes the term to indicate this new cultivation system. Both of them belong to the general category of vinetum.

Virgil, in the Georgics (29 B.C.) describes the viticulture of his land (Mantua) and tells that the vines were married to the elm.

Columella, in the De Re Rustica (65 AD), the first real agrarian treatise in history (it will remain the basic text for all the centuries to come, until at least the 18th century), describes the different systems of Roman viticulture. However, the increasing prevalence of the vinea to the detriment of the arbustum emerges, because the first guarantees viticulture that is more specialized.

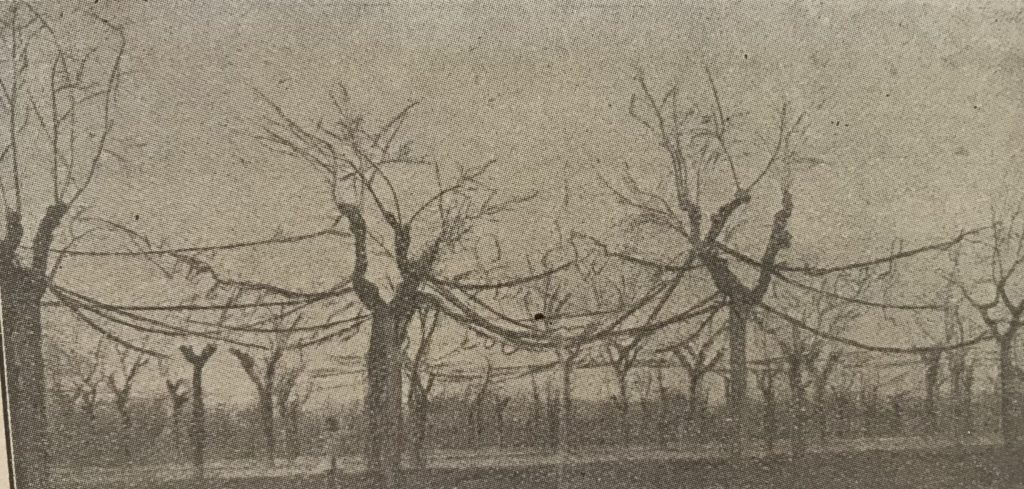

Pliny the Elder (Naturalis Historiae, 77 A.C.) tell us about the viticulture of Campania at the time, with vines married to the poplars, even very tall, especially in the area of Aversa. He distinguishes the arbustum italicum, where the vines rise on the single tree, from the arbustum gallicum (so called because it was very common in Cisalpine Gaul), where the vine shoots are passing from one tree to another and forming rows. Pliny was also a wine producer: he sold large quantities of it in Rome, producing it in his farms in Campania, from married vines.

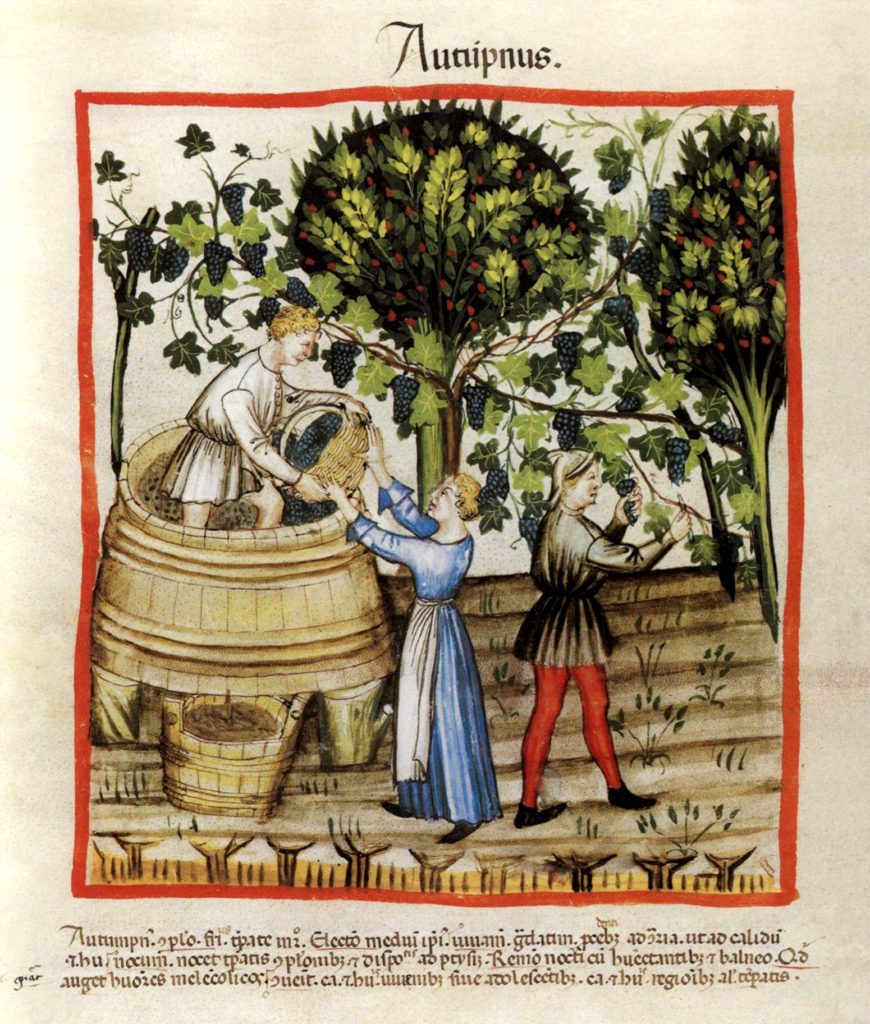

The married vines also return in to less relevant works of the late empire, such as the Opus Agricolturae by Palladius (4th century AD) and the Geoponica by the Byzantine Cassianus Bassus (6th century AD) which advises them in damp soils. In medieval period, we can find them in the work by Crescenzi (from Bologna), the only relevant medieval agricultural text of the European Middle Ages (1486).

In 1644, the Bolognese agronomist Vincenzo Tanara describes the two main systems of married vine of his time, which correspond to the Roman systems. He calls them “piantata” (the arbustum gallicum) and “alberata” ( the arbustum italicum), terms still used in modern Italian.

For all the following centuries, these two systems dominated the viticulture of the Center and the North Italy, depending on the area. The alberata were plots with vines climbing single trees, randomly positioned in the field or with regular arrangement. Native from central Etruria, they remained traditional especially in Tuscany (with the name of “testucchio”) but also Lazio and Umbria. The piantate instead was formed by rows in the border areas of the fields or along the banks of the ditches. They were more widespread in the north-central part of Etruria and in the areas of expansion to the South. In fact, they remained traditional especially in the Po Valley and Campania.

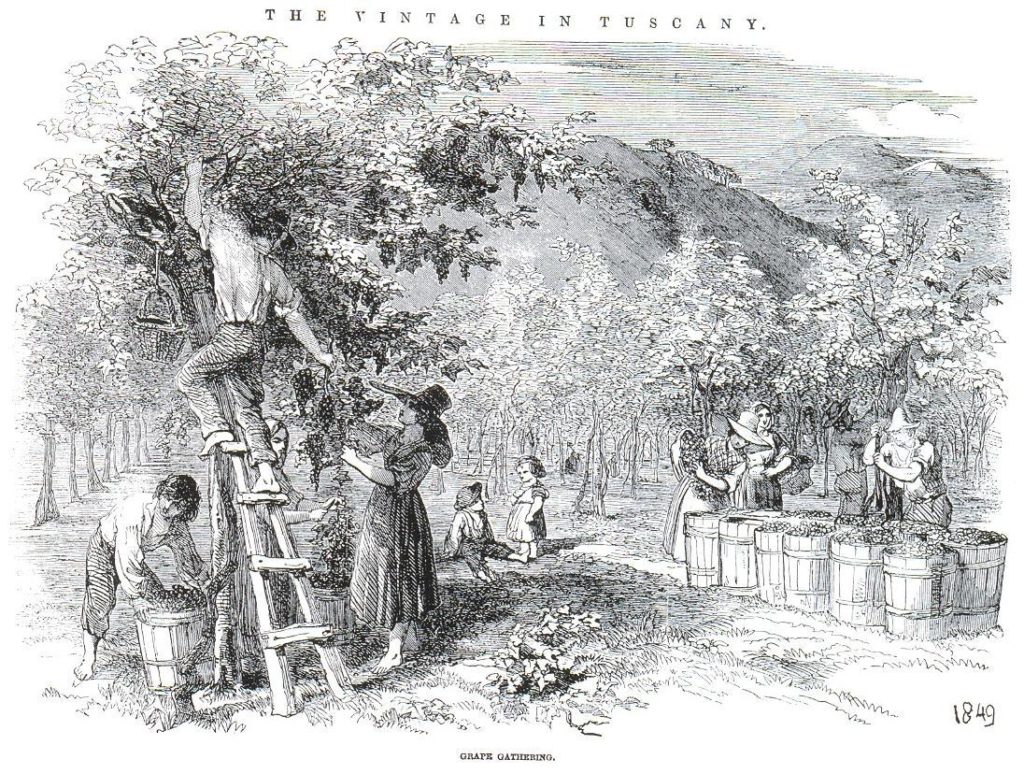

Therefore, the married vine continued to be part of the Italian rural landscape even after the classical era and it was depicted in the art of all centuries.

These landscapes also fascinated the foreign travelers of the eighteenth-century who were making their cultural journey in Italy, which was considered indispensable in the youth formation of the educated European class at the time. The landscapes with the married vines are in many paintings of that period. They are also told in the travel diaries, such as by the French architect Jacques-Germain Soufflot in the mid-eighteenth century, visiting Paestum (Suitte Des Plans, Coupes, Profils, Elévations géometrales et perspectives de trois Temples antiques, tels qu’ils existoient en mil sept cent cinquante, dans la Bourgade de Pesto… Ils ont été mésurés et dessinés par J. G. Soufflot, Architecte du Roy. &c. en 1750. Et mis au jour par les soins de G. M. Dumont, en 1764, Chez Dumont, Paris, 1764), or by Goethe with his famous “Journey to Italy” (1813-1817).

The image so evocative of the vine that embraces the tree, however, did not remain confined only to agrarian contexts. He also lit the imagination of artists and writers, who gave them different symbolic meanings.

From the first century AD, the poetic metaphor of the vine and the tree (especially the elm) appeared in the Latin literature as a symbol of indissoluble love. The vine is “married” to the tree: hence the term vitis maritae (vite maritata, in Italian) which we still use today (“married vine”) was born.

For example, Gaius Valerius Catullus identifies the vine and the elm as a wife and husband in the “Bridal Song of boys and girls” (Carmina, poem 62, translation by E. T. Merrill):

“… As the widowed vine which grows in naked field never uplifts itself, never ripens a mellow grape, but bending prone beneath the weight of its tender body now and again its highmost shoot touches with its root; this no farmer, no oxen will cultivate: but if this same chance to be joined with marital elm, many farmers, many oxen will cultivate it: so the virgin, while she stays untouched, so long does she age, uncultivated; but when she obtains fitting union at the right time, dearer is she to her husband and less of a trouble to her father.”

In the Metamorphosis of Ovid (XIV, 623 and following), this metaphor appears in the love story of Vertumnus and Pomona. Vertumnus was a God of Etruscan origin, also remained in the Roman religion. He was the God of the transformations (verto, in Latin, means in fact change): of the change of the seasons but also of the trade. The God fell in love with Pomona, a very ancient Latin goddess of the cultivation of the fruits, which, however, was unapproachable. He tried to reach her with different disguises, and he had succeeded when he took the form of an old woman. Then, he tried to convince her to abandon herself to love with various arguments, including the metaphor of the vine and the elm:

“There was a specimen elm opposite, covered with gleaming bunches of grapes. After he had praised it, and its companion vine, he (the “old woman”) said: ‘But if that tree stood there, unmated, without its vine, it would not be sought after for more than its leaves, and the vine also, which is joined to and rests on the elm, would lie on the ground, if it were not married to it, and leaning on it. But you are not moved by this tree’s example, and you shun marriage, and do not care to be wed. I wish that you did!”

(A. S. Kline‘s Version)

At the end of the speech, Vertumnus revealed itself. Pomona, struck by the words heard and the beauty of the God, gave in to love.

This story had great success in the Renaissance and it will remain a very frequent artistic themed until the eighteenth century.

Again, we find in Ovid (Amores, elegia XVI) this theme:

Ulmus amat vitem,

vitis non deserit ulmus;

Separor a domina

cur ego saepe mea?

(The elm loves the vine

The vine does not desert the elm;

Why so many times am I separated from my beloved?)

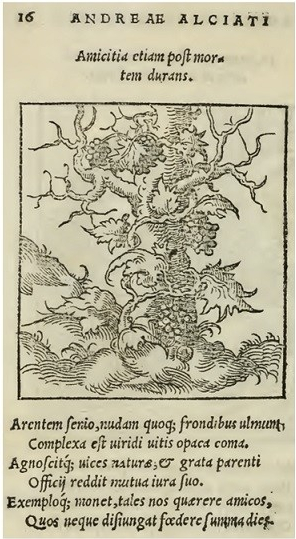

The theme of the vine married to the tree, however, reached its maximum diffusion thanks to the Milanese jurist Giovanni Andrea Alciato or Alciati (1492-1550). He published a collection of allegories and symbols (reproduced with woodcuts), explaining their moral value with short texts in Latin. The title was “Emblemata“, published in Augsburg in 1531. It was an extraordinary success throughout Europe, with translations into Italian, French, Spanish, German and English. Alciato created a real new literary genre, of great success even in the following centuries, the emblem book.

Alciato reported the married vine as the emblem of Friendship and, in its purest form, of Love, with the Latin title:

“Amicitia etiam post mortem durans”

(Friendship that lasts even after death)

This interpretation was influenced by an epigram of the Greek poet Antipater of Thessalonica (1st century BC), in which a withered plane tree tells how the vine, climbed on it, keeps it green. Alciato, who is from Lombardy, corrects the Greek’s error. The married vine was part of the agrarian landscapes of his native land and therefore he knew very well that it is the elm the ideal husband of the vine, not the plane tree.

Thanks to Alciato and to the success of the emblem book, the symbol of the vine married to the tree had an enormous diffusion and appeared in many artistic representations, in poems and literary works from all over Europe. The married vine of Etruscan, with Mediterranean origin, thus became a decontextualized cultural symbol.

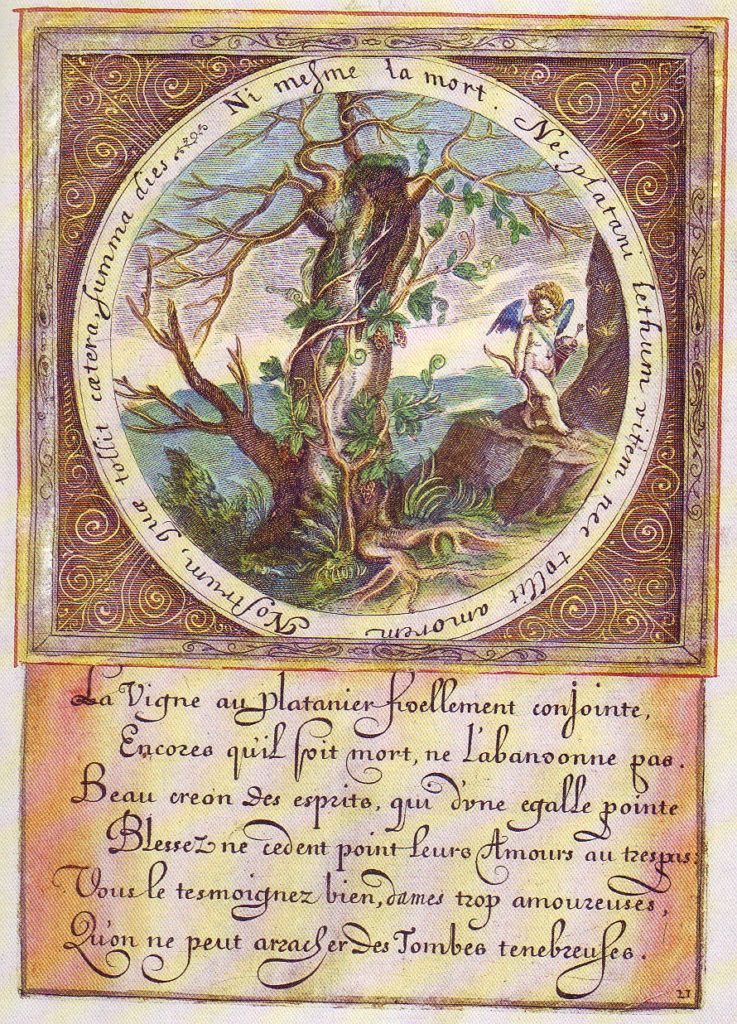

For example, the Flemish Daniël Heinsius, in Emblemata amatoria (1620), rather than to Friendship, returned to bind it to the Imperishable Love, as in the classical era. He returned to use the plane tree too, as in the original Greek epigram. The married vine is the emblem of an eternal love that goes beyond death, with the wording

“Ni mesme la mort“, not even death.

It also became the logo of the Elzevier, publishers of Leiden (Holland) from 1580. The current Elsevier publishing house (refounded in the nineteenth century) is the world’s largest medical and scientific publisher. Their symbol remains the original one, a life married to a tree, with the meaning of the alliance between learning and literature.

From the nineteenth century, viticulture became a science and many agricultural treaties flourished, that described in detail the traditional Italian systems. For this part, I referred to the works of two outstanding scholars of the nineteenth and twentieth century, Prof. Ottavio Ottavi and Prof. Domizio Cavazza.

The Italian viticulture of the time, in the center-north, had remained based of that of ancient Rome, with the arbustum italicum (alberata) and of the arbustum gallicum (piantata). These two archetypes, however, had given origin to a myriads of different systems, which (the same scholars admit) were difficult to list in all possible variants. Furthermore, there was a lot of confusion in terms at this point. The term “alberata” was used often to indicate one or the other system.

Especially the elm, maple and poplar were still used. Now we can also understand why.

The ideal, as living tutor, is a plant whit small root system and foliage, because they must not interfere with the development of the vine. The perfect tree is the maple (Acer campestris), the favorite for vines since the ancient Etruscans. It is slow to grow, it has few roots that go deep down and do not interfere with those of the vines. The pruning can model easily its small foliage. It also adapts well to poor and shallow soils.

The elm (Ulmus campestris) remains the most used tree in the north. It has a strong radical expansion but is very long-lived, it produces excellent fodder (leaves) and fagots and wood. It adapts more to the fertile and humid soils of the Po Valley.

The poplar (Populus nigra) was used because of its rapid growth and because it produces fodder and wood. It is not so suitable for the vine, because it has an extensive root system and too dense foliage.

The mulberry (Morus alba) was used above all in Veneto even though it was not suitable. It makes too much competition for the vine. However, it is suitable to put together two businesses: the grapes and the silkworm breeding. However, the introduction of copper treatments at the end of the nineteenth century (which kills the bug) made this coexistence very difficult.

In addition, these trees were used too, to a lesser extent: the willow, the manna ash tree, the ash tree, the dogwood, the lime tree, the hornbeam, the oak, the cherry tree, the olive tree, the walnut and the fig tree.

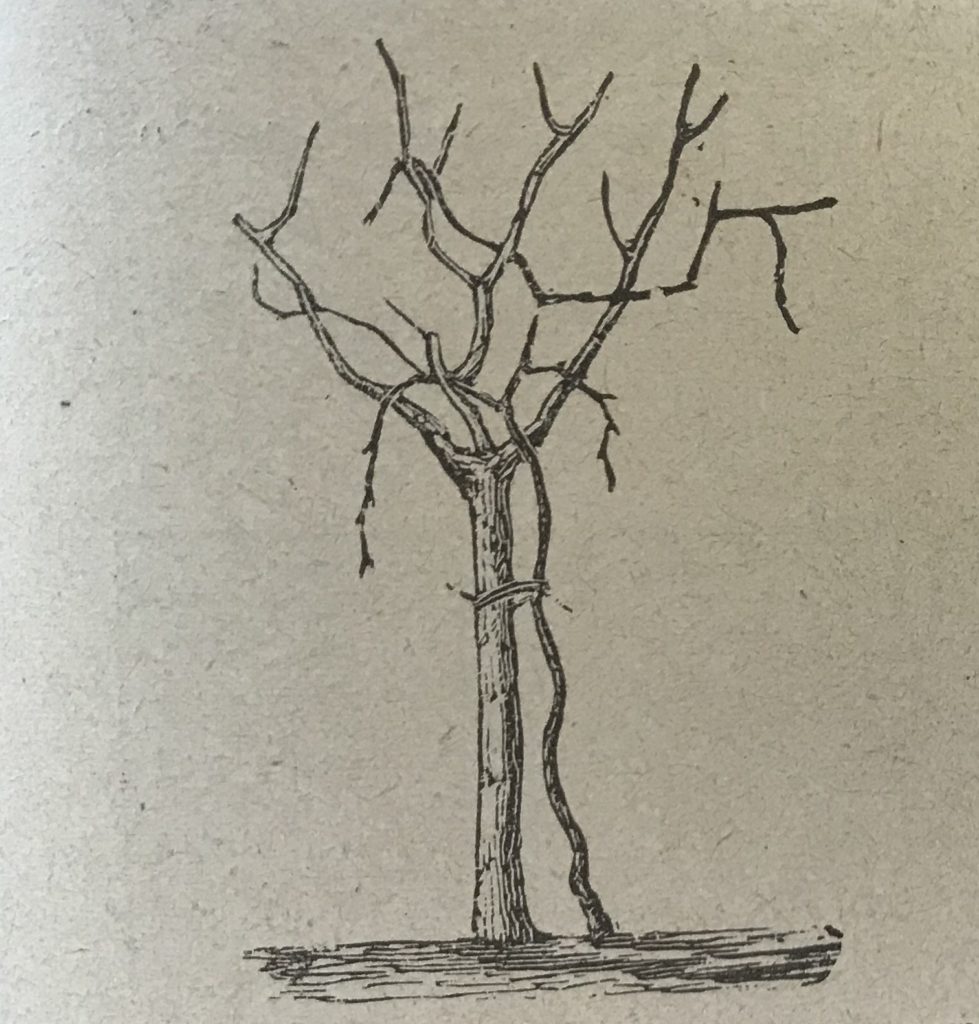

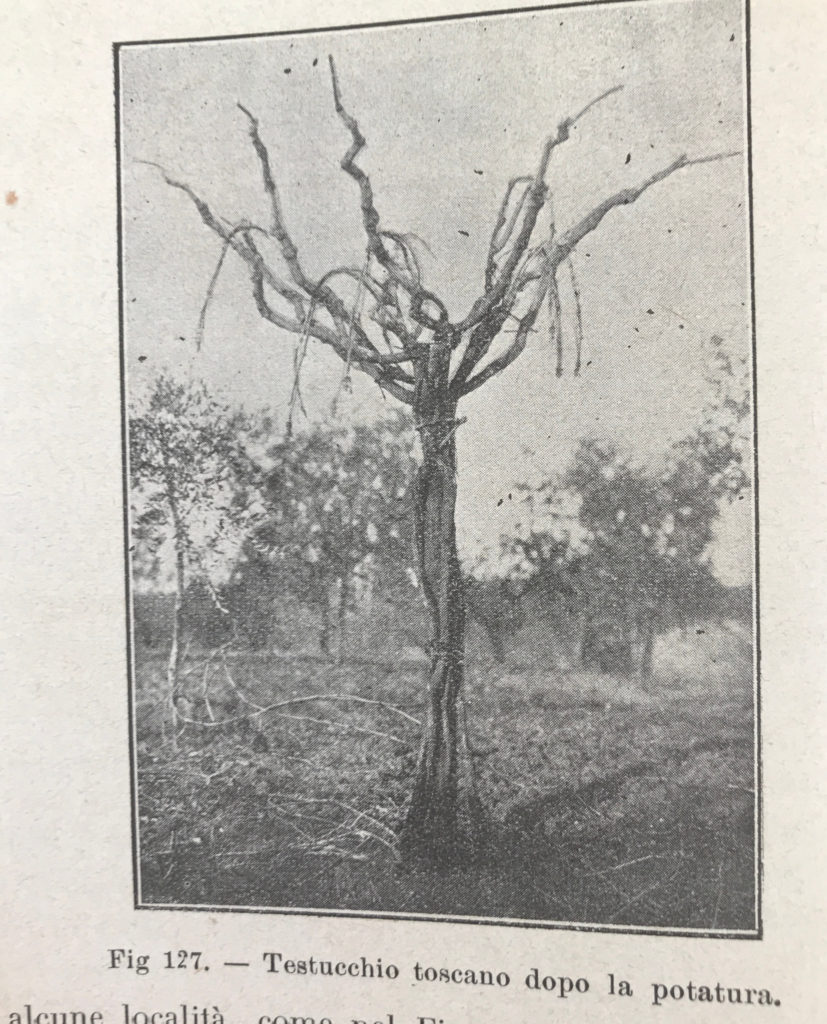

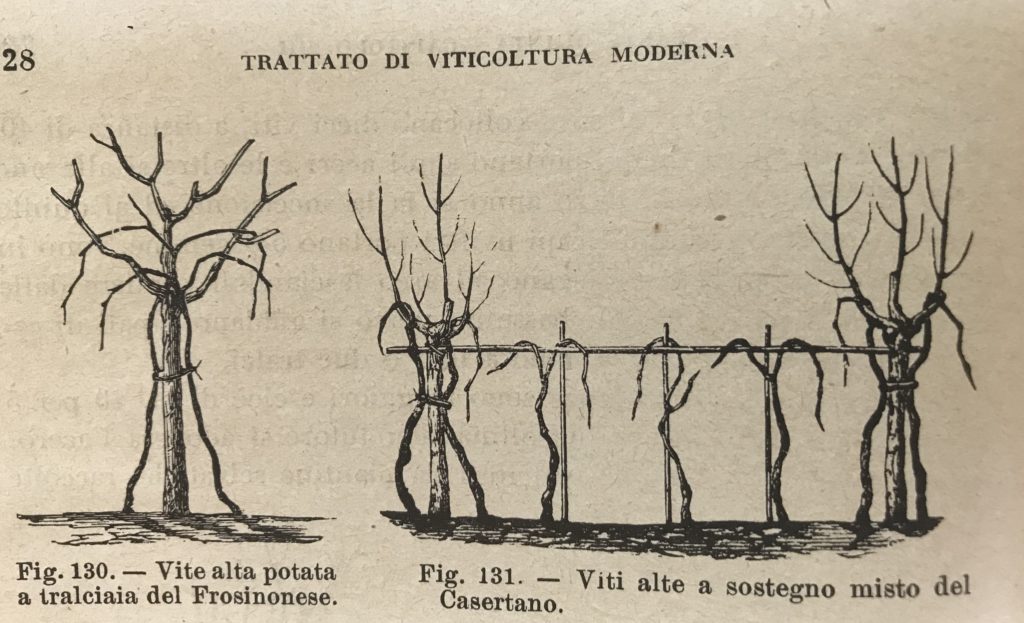

The simplest system, the old arbustum italicum, was called testucchio. It was widespread especially in Tuscany, but also in the Marche and Lazio, with a slightly different planting and pruning methods. Above all, maples were used, called oppi or loppi in Tuscany (acero, in Italian). Among the testucchi, the winegrowers could also grow low vines, resting them on poles, thus forming a complete row. In the Caserta area, there were similar solutions but with high vines.

In Abruzzo, the vine-shoots were intertwined to form a large horizontal square, forming the so-called capanne or capannoni.

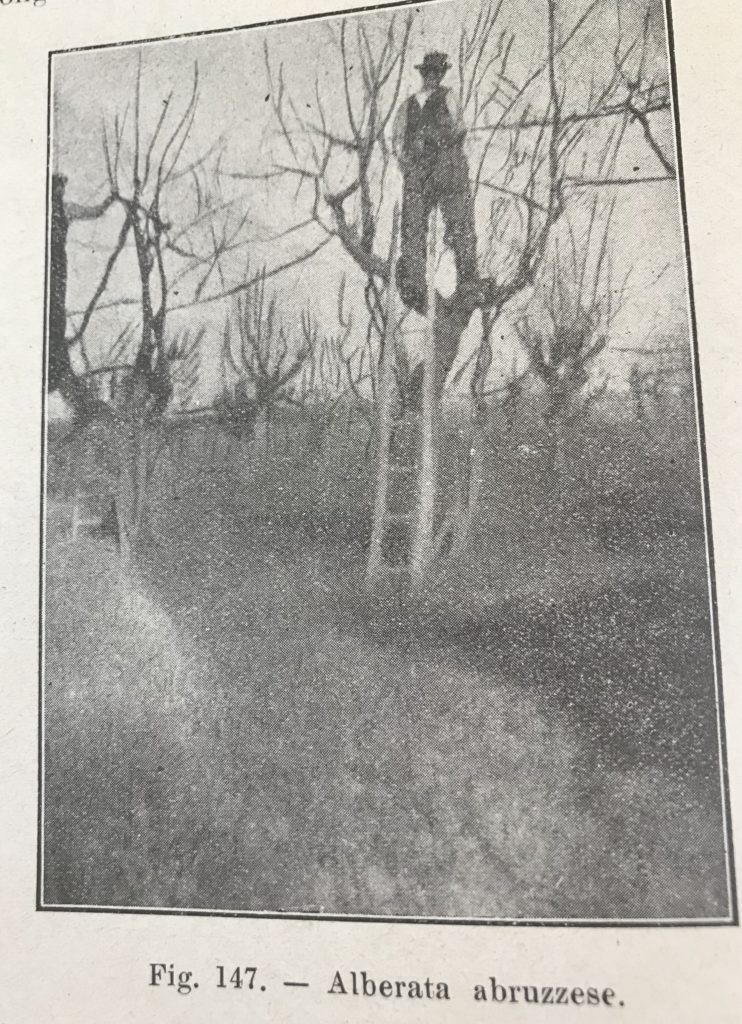

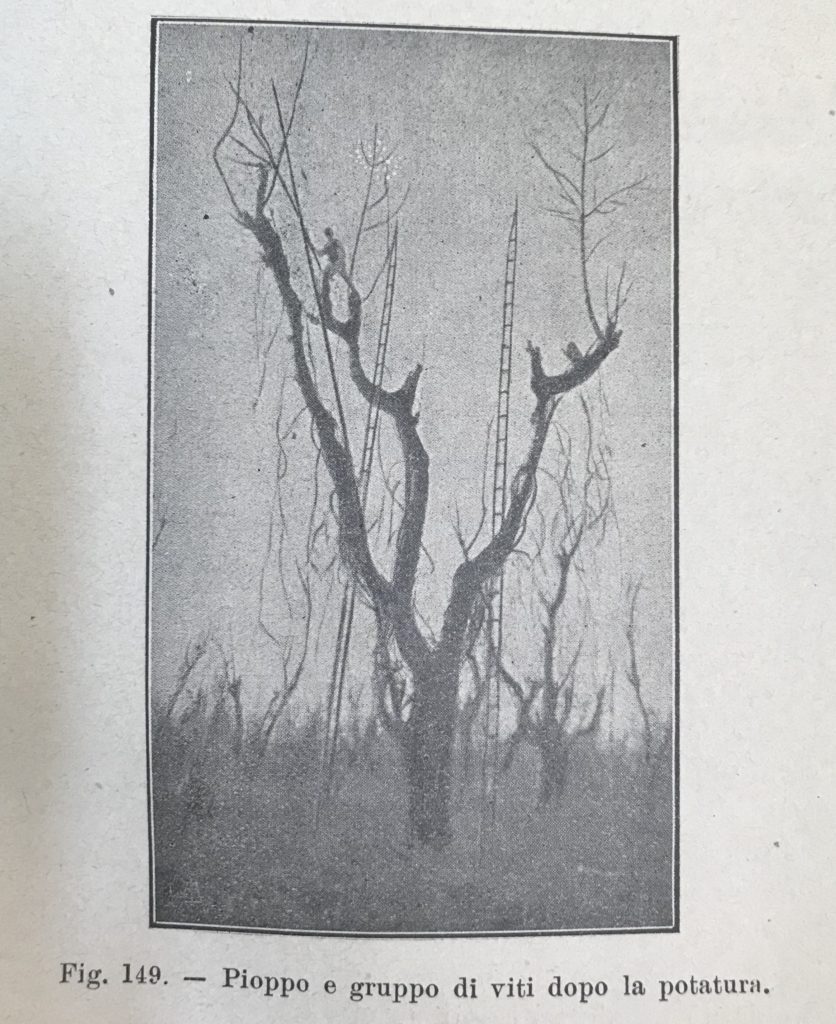

In the area of Aversa (near Naples), the cultivation of Asprinio grapes on poplars reached up to 20 meters in height. Note, in the photo, the size of the man on the tree. In the inter-row, the winegrowers grow other species such as hemp, corn, potato and various cereals.

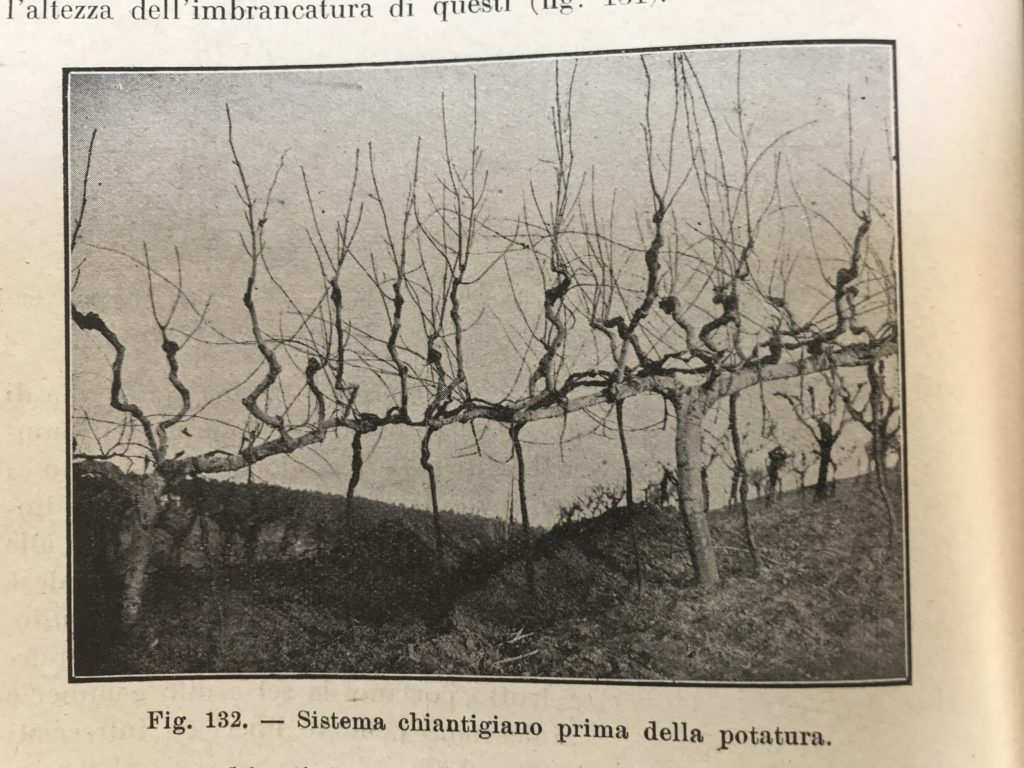

The “Chianti system” was based on the maple trees, whose branches were pruned to stand horizontally and join those of the neighbors, obtaining a sort of continuous espalier on which the vine climbed.

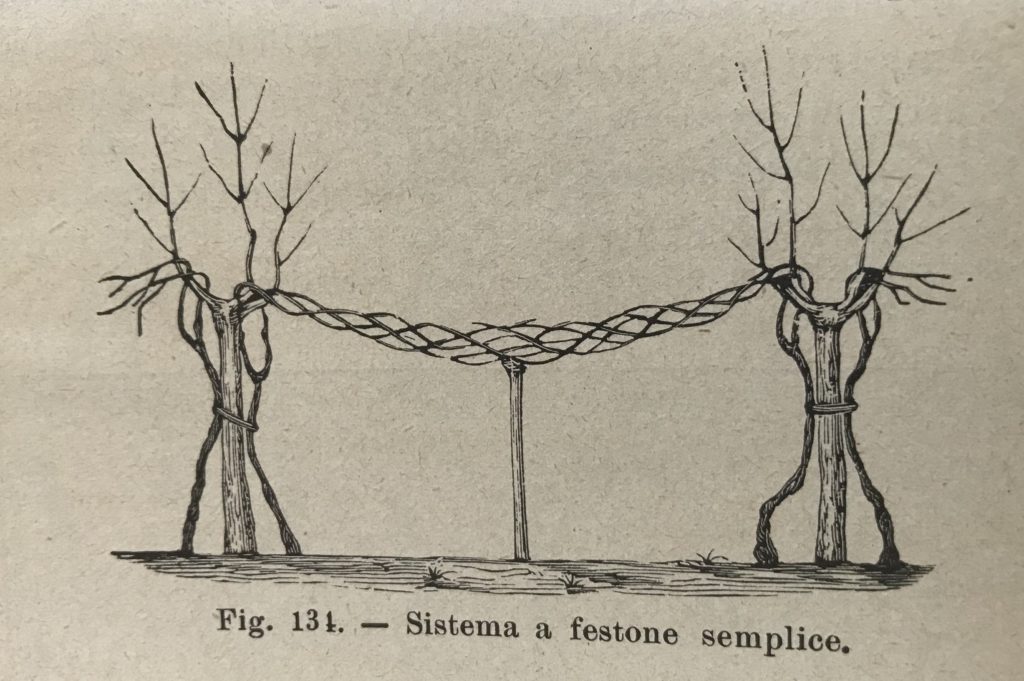

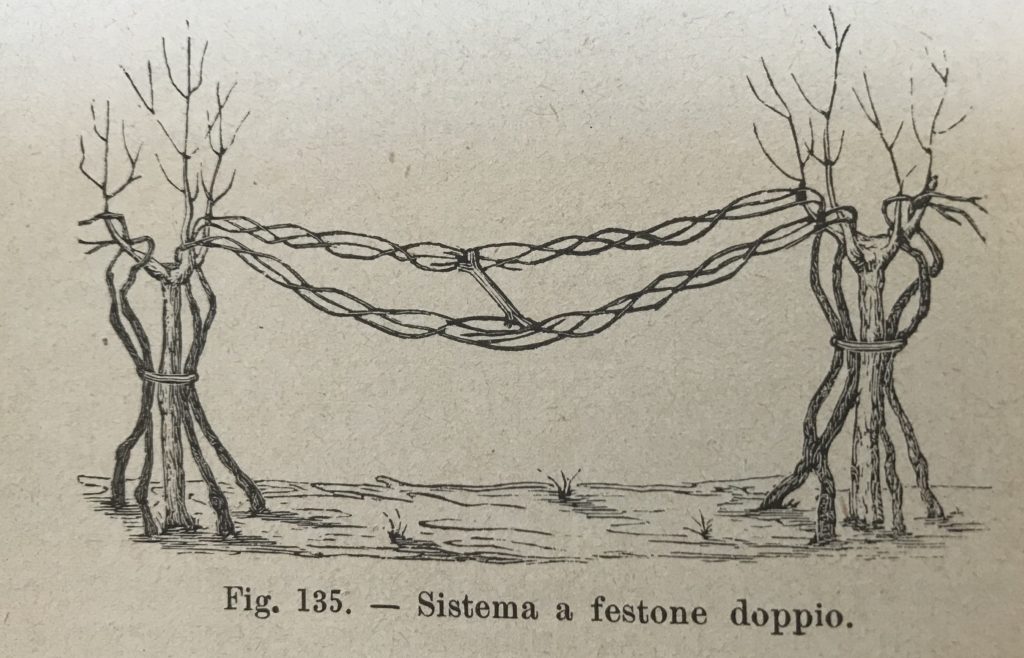

The “festoons system” (or “tralciaia” or “pinzana“) was typical of the areas of Pisa (Tuscany), Caserta, Naples and the Emilia. The festoons were formed by very long intertwined vine-shoots. Sometimes they had to be hold up by sticks or separated by a crossbar.

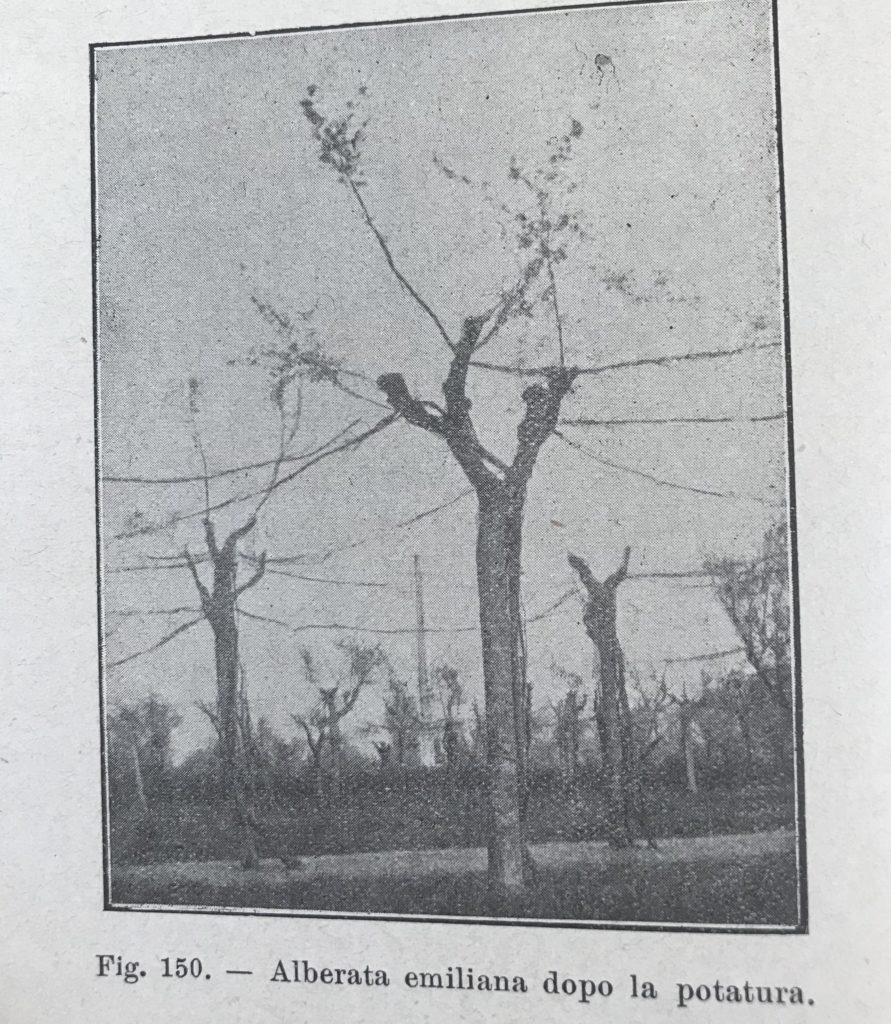

In Emilia it was mainly used the elm, in Romagna the maple, both much lower. In the area of Ferrara, the vines were very high on walnut trees. In these zones, the rows of “married vines” were often on the edge of the fields and along the ditches.

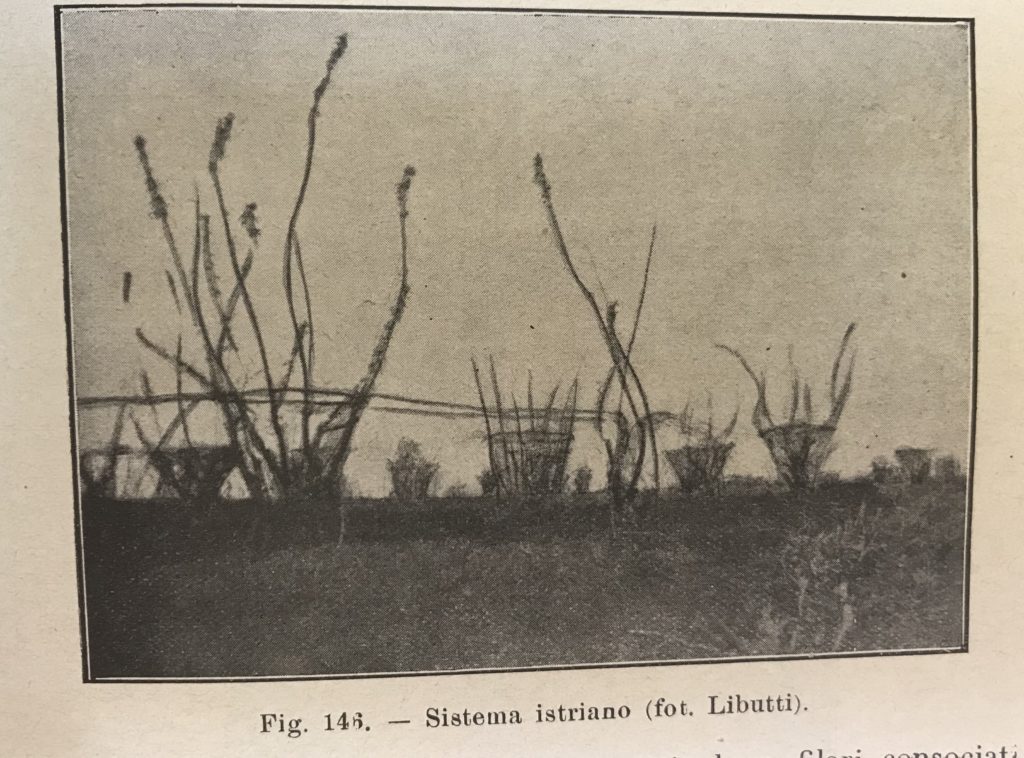

The “Istrian system” was based on low-grown maples or ash trees, like stumps, from which numerous branches spread out, which were joined to form a circle at a certain height. The vine-shoots stretched up to the circle, then spread out and joined the neighboring trees. This system was used for local varieties such as Terrano, Isolana, Nera tenera and Crevatizza. Prof. Ottavi says that this system was disappearing already at its time.

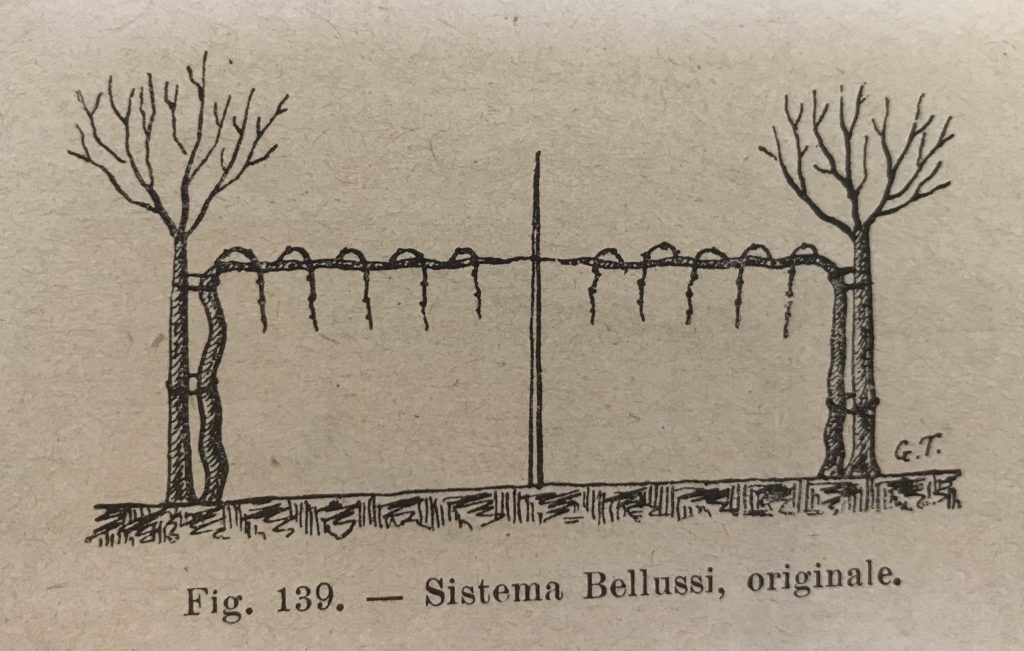

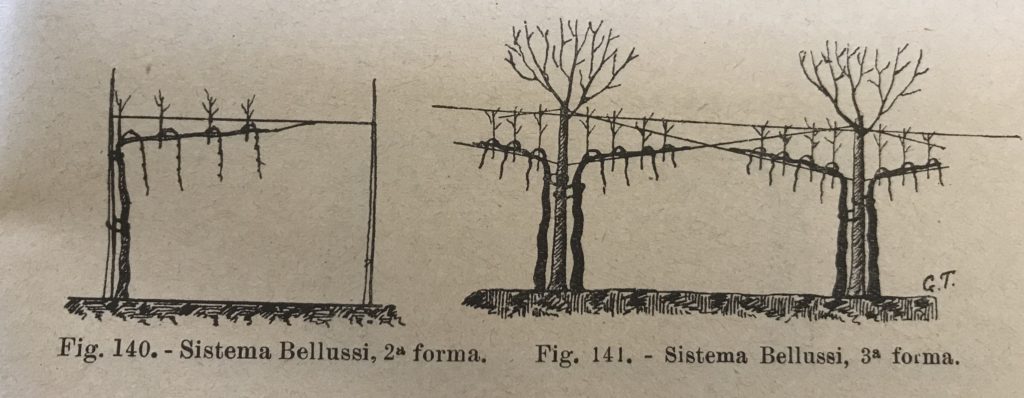

In the nineteenth-twentieth century, some new mixed forms evolved from the more traditional ones, with wires and poles together with trees, to try to modernize this type of vine-training system. An example was the “ray system” or Bellussi (from the name of the inventors). It was widespread especially in Veneto. The ray systems presented numerous variations.

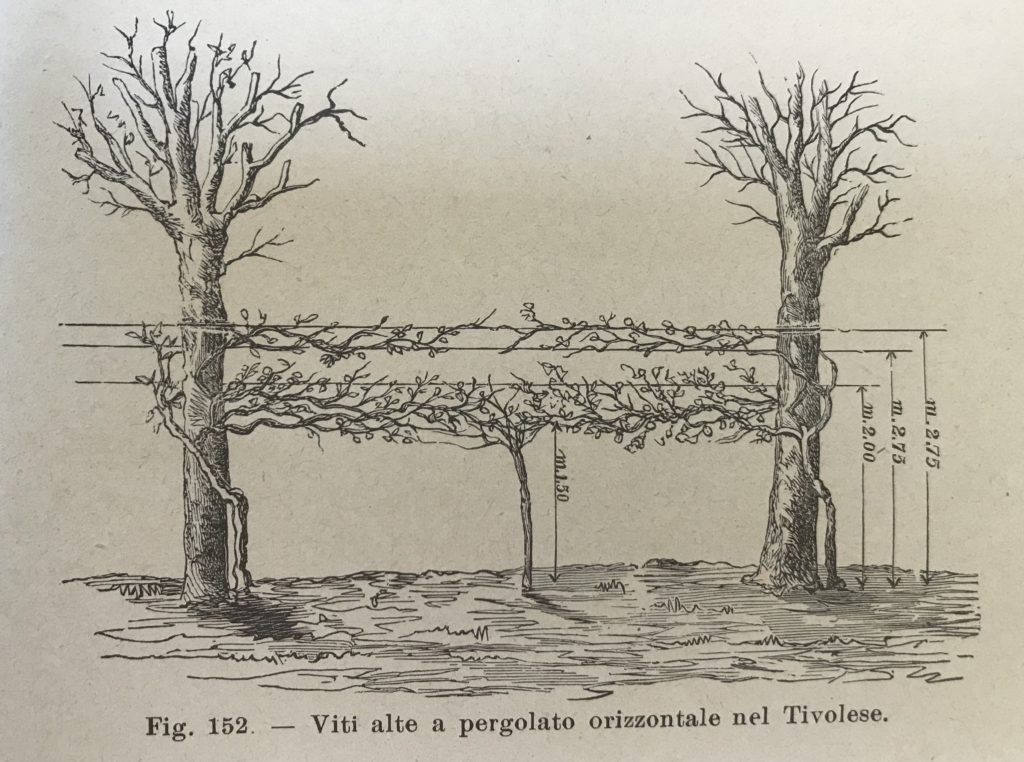

The mixed pergolas consisted of trees with wooden scaffolding and iron wires. They were located in Tivoli area, in Piedmont and in Emilia.

In any case, in the twentieth century this ancient culture has disappeared.

From 1920, a fungus from Asia decimated the elms (the Dutch elm disease, DED, “grafiosi” in Italian).

In ’20s, Prof. Cavazza explained that the gradual disappearance of the “married vines” was due above all to changed technical and economic conditions. He lists the disadvantages of this system with respect to the “dead” tutor (a pole): it takes more time to reach normal production, the trees shade the vine, the grapes mature later, there is greater need for fertilizer (both for the vines and the trees), greater difficulty and expense in pruning and all other work (from treatments to harvest).

Yet he had resisted for a long time even for undoubted advantages, listed by Cavazza himself, as the great longevity of the vineyard. In addition, the tutor trees also give useful products to the farm, such as fodder for animals and faggots. The trees partly protect the vines from frost and hail. Among the trees the winegrowers can cultive other crops… It is simple to understand as these advantages belong however to a promiscuous agriculture, to an old rural world that was not able to exist more.

In fact, above all after the Second World War, the Italian viticulture had a profound transformation. The modern production required a highly specialized viticulture. In this new world, there were no place for the “married vine”, survived for over three thousand years.

If you want to see an Etruscan vineyard, you can come to Guado al Melo: we created it with local wild vines. Alternatively, you can still find one of the above systems in Aversa zone or in some small estates of Tuscany and Emilia Romagna.

Italy has certainly sacrificed much of its rural culture to modernity. The important thing is not to lose its memory, because it is part of our history. This is why a “married vine” is on the label of our wine Atis (Bolgheri DOC Superiore).

Not even death

Nella prossima puntata scopriremo invece le varietà ed i vini Etruschi, oltre che le modalità di vinificazione.